A Safety Journey

Nov 23, 2022

Your author reflects on his 45 years in the industry through the lens of safety.

With the focus of this issue on safety and as one of a handful of the dual-qualified Chartered Engineers and Chartered Safety and Health Practitioners in the industry, I reflect upon my journey (a description reflective of a constant process of learning and personal development). In doing so, I draw upon my 45 years of experience, initially 10 years as a spanner-wielding lift engineer, followed by 16 years in management and 19 years as a consultant.

Having entered the workplace in 1972, I am able to consider approaches adopted prior to Britain’s accession to the European Communities (EC) in 1973 and those prior to the Health and Safety at Work Act (HSWA) 1974 together with developments in workplace health and safety through to the present day.

What inspired me to become a health and safety practitioner? I recall a day in the 1970s when, as part of an annual clean down and inspection, I was persuaded to travel down inside an escalator step-band. Whilst clearly inappropriate and highly dangerous, the intent was to shorten the process. My naivety in this respect, coupled with my observation of our work at height practices (100 m up, working with ladders more often unfixed, and without harnesses and/or fall protection), together with observations in relation to some accidents and near-misses, served to spark my interest. I recognised that there were better and safer ways of doing things.

I studied what was then the National Association of Lift Manufacturers (NALM)/Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) Managing Safely® course as part of my lift engineer training and later, as part of an engineering degree, I studied integrated environment, health and safety at the post-graduate level. This included forensic engineering and quality management, such that I was able to successfully apply for MIOSH Member status. With further study for a Master of Laws (LLM) in health, safety and environmental law at Salford, I attained CMIOSH Chartered Member status.

I recall the dramatic effect the HSWA 1974 exerted upon lift industry management and other duty holders in terms of safe working practices. The Act initiated a commercial windfall for contractors in terms of retrofit works, including the provision of lift car top controls, pit stop switches and pit access provisions. Previously, the safe practice of the time involved travelling on lift car tops at full speed (in a downward direction by way of a safety precaution). Whilst this mitigated the risk of crushing against the top of the lift shaft, travelling at full speed (using only a stop switch) was, by today’s standards, hazardous.

The introduction of the 6-pack of Regulation and the European Union Open Market in 1992 further improved safety provisions. Risk assessment under the Management of H&S at Work Regulations (MHSWR) 1992 and physical improvements under the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER) 1992 (which applied retroactively to existing workplaces) drove significant change. Oddly, we continued to undertake statutory examinations under Section 22 of the Factories Act 1961 using the prescribed Form 54 until the introduction of the Lifting Equipment and Lifting Operations Regulations (LOLER) 1998 and the update of PUWER 1998.

The 1987 fire at King’s Cross underground station placed the focus on escalators and the maintenance of these, initiating a wave of improvement projects to remove flammable materials from their construction.

I first gave evidence in Court during 1990: in this case, in the County Court on behalf of Otis in a commercial claim. This sparked an interest in law and, subsequently, my legal studies, which culminated in the Bar Vocational Course and call to the Bar by Middle Temple.

In 1994 came the first incarnation of the Construction (Design & Management) Regulations (CDM) 1994, introduced to address a recognised unsatisfactory H&S performance in the construction industry. Having worked under the 1994, 2007 and 2015 versions of CDM, I agree with Dame Judith Hackett’s view that the CDM 2015 represents the most effective regulation developed by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), albeit that this involved a level of iterative trial and error over a 20-year period.

Nowadays, I am able to predict how well a project will develop simply by looking at the management of EH&S and welfare on the site. Poor EH&S management reflects a poor organisational culture, which will not produce effective results.

In 1999, the Lifts Directive 95/16/EC (UK Lifts Regulations 1997) introduced the most significant sector specific regulatory change since the Factories Act 1937.

The Directive was updated as 2014/33/EU (UK Lifts Regulations 2016). Whilst the revision introduced additional safety provisions, a significant element of its content involved a revision of provisions of 95/16/EC, which had proven unsatisfactory, resulting in a deterioration in design and product safety.

The COVID pandemic involved services for the NHS in terms of equipment modification for COVID management, together with fire inspection and providing testing on high-rise buildings and statutory inspection of various items of plant installed in essential facilities.

Nowadays, I am able to predict how well a project will develop simply by looking at the management of EH&S and welfare on the site.

In terms of accident/incident investigation, my experience is of an inappropriate trend in industry safety managers adopting an overly defensive/protectionist approach, sometimes to the extent that this is detrimental to the safety of the workforce and general public. Whilst this may be understandable in terms of corporate pressures and the stressful nature of such situations, it is unhelpful in terms of developing understanding and in preventing future failures. A greater exercise of independence would assist, perhaps by way of a greater professionalisation of the role within the industry, such as applies to IOSH professionals.

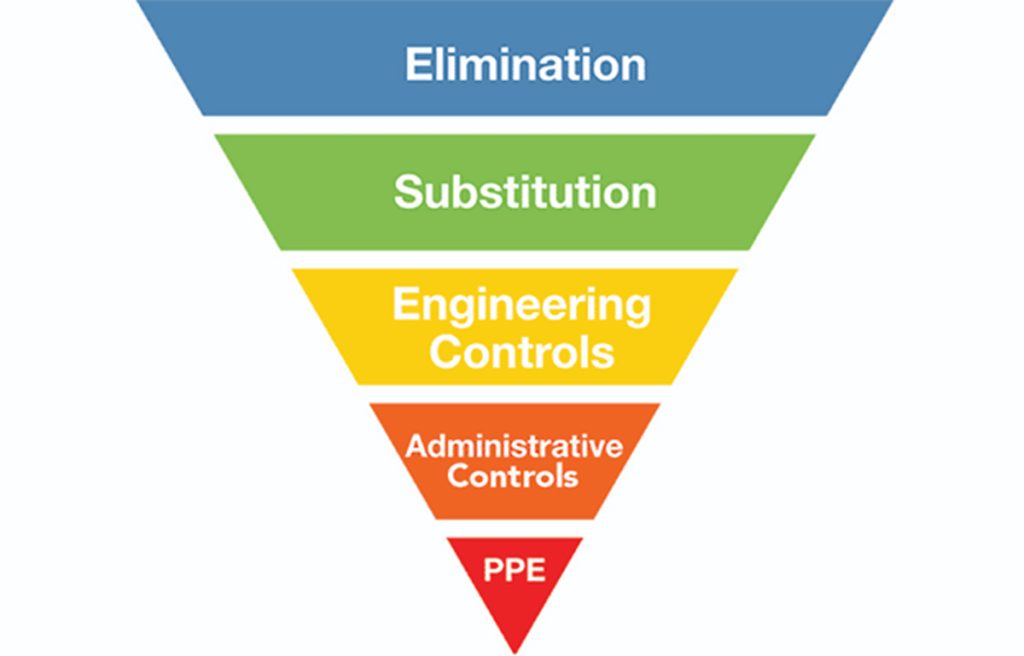

The emergence of a command-and-control approach to contractor safety management, initially revolving around the application of PPE, and as a means of implementing cultural change, has proven counterproductive, generating resentment in the workforce. This narrow focus on compliance results in failures to recognise and deal with serious deficiencies in work processes and practices.

The management culture promoted by IOSH is far more effective in driving cultural change whilst retaining the engagement of the workforce. Indeed, my experience is that if people can understand what they are asked to do, together with the reasons for this, the change process becomes effective and ingrained with the desired practices integrated into the work process with enhanced workforce engagement.

The CDM role of Principal Contractor is not as well understood and/or implemented in the industry as it should be. In the main, this is a result of shortfalls in the training of contractor managers, and deficiencies in knowledge and training in the consultancy sector. Consultants produce “designs” and often undertake the principal designer role in works on existing installations, potentially exerting a significant influence, for better or for worse, on safety in the sector.

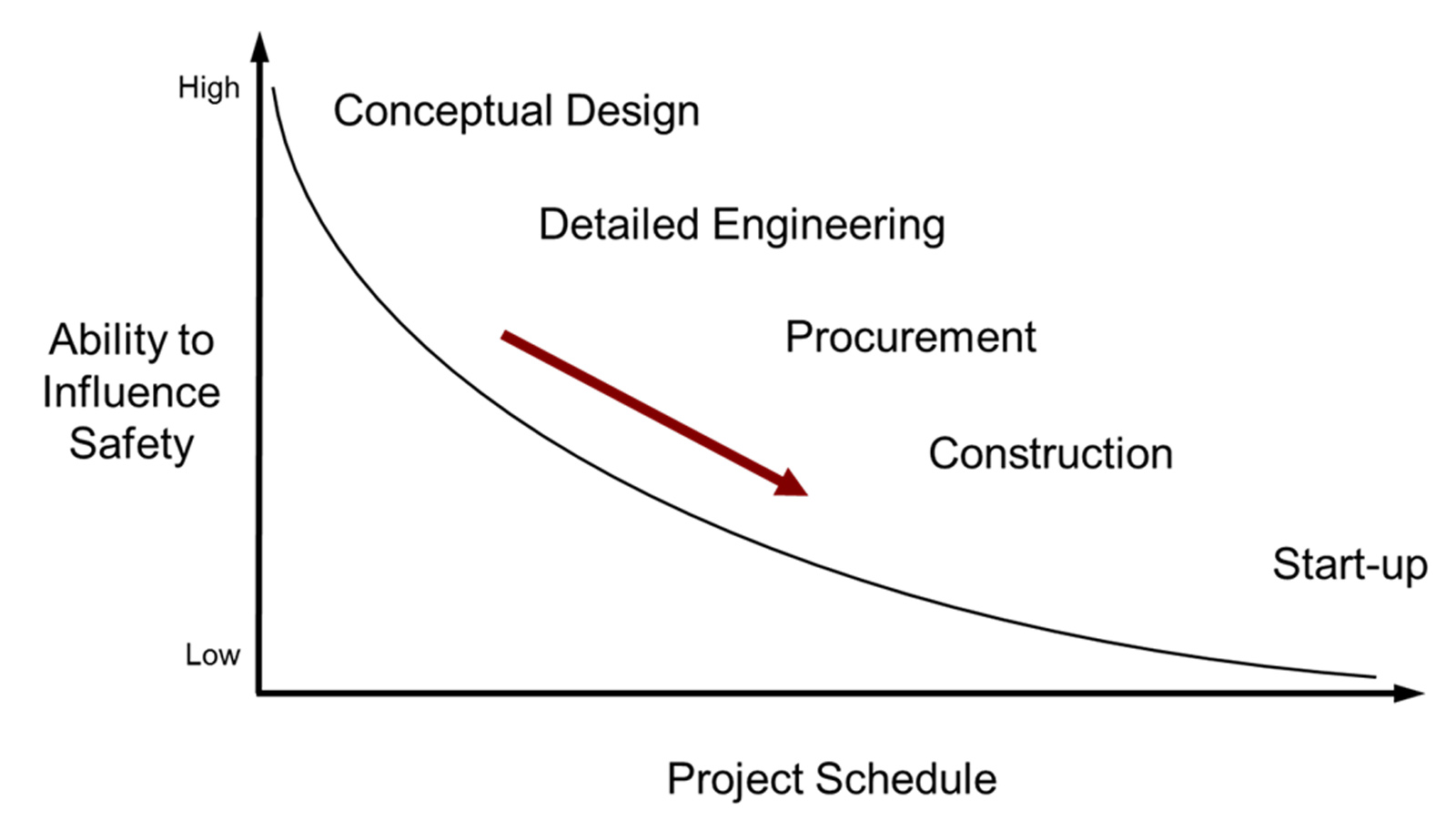

When developing and/or delivering training, I have drawn upon a model relating time and design to safety (reproduced as Figure 1) and the Hierarchy of Controls (reproduced as Figure 2), which I think demonstrate very clearly the link between design and construction and the amplifying effect that decisions taken at the design stage of a project can have on safety and cost problems later. The amplification affects the whole lifecycle of an installation, with maintenance activities no longer as safe as they should be. In this respect, I am a firm believer in the integration of EH&S in the design team and, thereafter, carried into the construction phase for any project.

The influence exerted by the industry’s six major international firms is both productive and counterproductive in terms of working practice. Clashes of culture give rise to misunderstanding, frictions and conflict, although by way of a positive, a sharing of practices drawn from other jurisdictions can prove enlightening in terms of process improvement. Having undertaken assignments in the major states of the EU, I have observed first-hand how cultural differences in understanding and in the interpretation of practice and regulation can lead to misunderstandings and friction. A key skill of the practitioner and consultant lies in the understanding and management of these cultural factors such as to produce satisfactory outcomes.

An inappropriate application of organisational theory has resulted in the introduction of non-engineers into line management positions. These managers lack the knowledge and understanding necessary for them to be effective in their roles. As a result, the safety of the workforce and others affected by the work is potentially compromised. A secondary effect lies in a loss of workforce confidence and of respect for the manager, further exacerbating the problem.

The U.K. political rhetoric and focus on deregulation and the promotion of self-regulation, with reduced levels of inspection and proactive enforcement activity has, in my view, proven counterproductive and detrimental to safety. The Grenfell Tower disaster brings to bear a focus upon the resilience of firefighting lift systems and upon designers and other duty holders under the CDM and Building Regulations. The emphasis on building safety will, I hope, operate to professionalise the industry’s approach to safety, design, testing and maintenance.

I note how some of the traditional causes of failure have receded and/or disappeared, due in the main to the application of new technologies, and I also note how these technologies introduce other hazards and modes of failure that we struggled to recognise. However, overall, the industry has made significant progress in terms of where it was in the 1970s and its position today.

The long-running debate on the relative prevalence in importance of training and/or experience is that a combination of both is essential in developing a well-rounded practitioner. I also recognise the excellent practitioners and engineers who have supported me in my journey and without whose influence I wouldn’t have progressed. I have given back by being an End Point Assessor for the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) Apprentice Programme for more than three years now. Previously, I served on IOSH development teams. I would recommend a career in engineering and EH&S to anyone starting out today, together with early engagement with IOSH and engineering institutions.

Working as an expert witness has provided a wide scope of experience in hundreds of accident and failure investigations, including design failures, component and materials failures, structural failure, management failures, noise and vibration, lifting operations, work at height, regulatory compliance, machinery design, ergonomics and manual handling and commercial contracts and dispute resolution.

I have enjoyed my journey in seeking to integrate EH&S with engineering design and management. Intellectually, this has been stimulating and challenging, as well as rewarding and enjoyable, particularly in merging practical experience, academic study and elements of law and regulation. Overall, the challenges presented in developing and assuring safe systems of work in a wide range of commercial, engineering and construction environments have been both rewarding and enlightening, and one never stops learning.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.