Conclusion of The American VT Industry in the 1880s

Mar 1, 2025

A look at early elevator call systems

The emergence of an industry sector that supplied many vertical-transportation (VT) companies with elevator call systems (typically referred to as elevator annunciators in the 19th century) serves as further evidence of the VT industry’s maturity in the mid-1880s. Thus far, 12 companies have been identified that manufactured elevator annunciators, and there are doubtless more waiting to be discovered. The history of these companies, and their embrace of the VT industry, illustrates the intersection of two dynamic areas of 19th century technological development: building communication systems and building transportation systems. The development of enhanced building communication systems was directly linked to the emergence of electricity as a viable power source for these systems. Early communication systems were powered by batteries (the first electrical power station did not appear until 1882, which provided power for electric lights for Wall Street and the New York Times).

By the early 1870s, a robust market had developed for internal and external building communication systems. The latter were typically advertised as “burglar alarm telegraphs,” which were designed to protect “invisibly, by means of electricity, each window and door … from burglars.”[1] When the system was activated, and a door or window was opened, a “telegraphic” signal was sent either to the company that maintained the system or to a local police station. Internal building systems included electric hotel annunciators, which allowed guests to communicate with the front desk from their room. These types of systems were also employed in office buildings. The application of a building communication system to a VT system required the designer to overcome a factor not encountered in other settings: the movement of the elevator car.

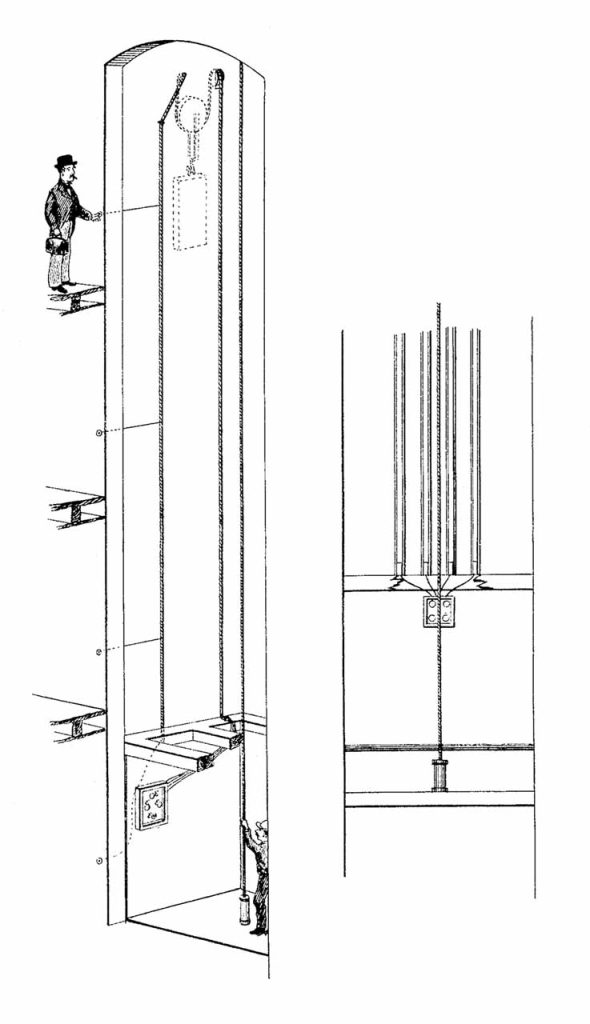

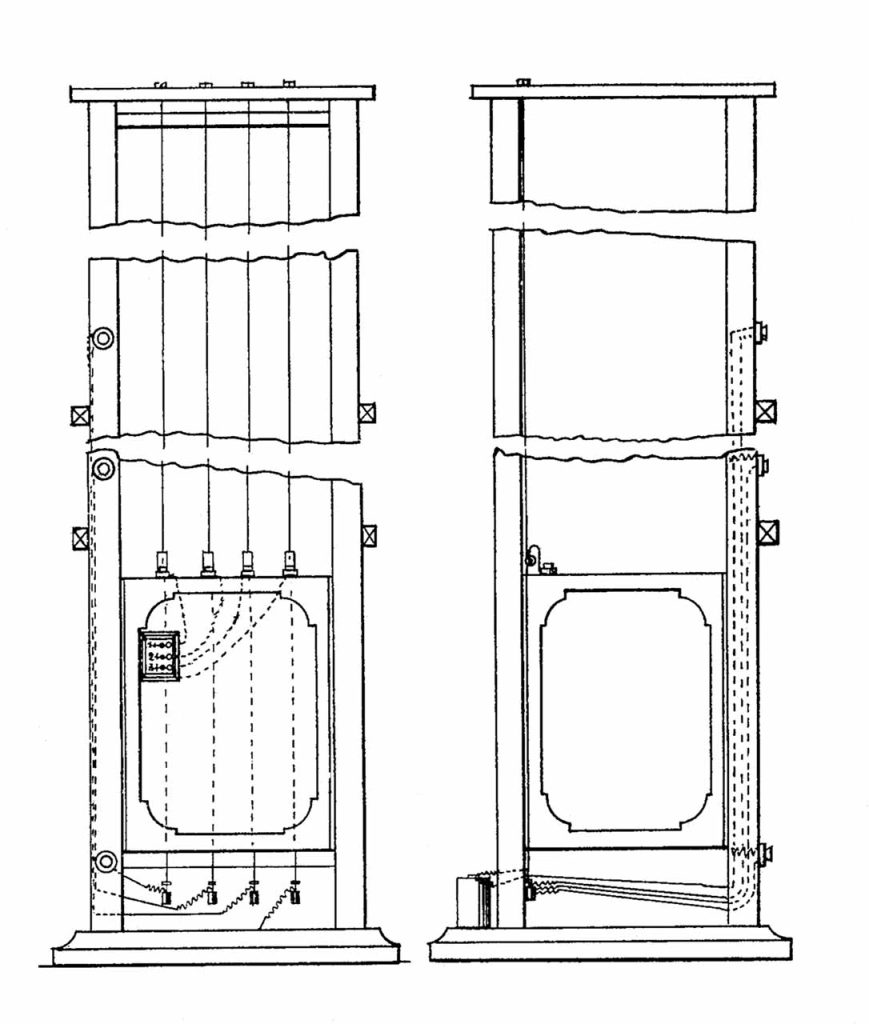

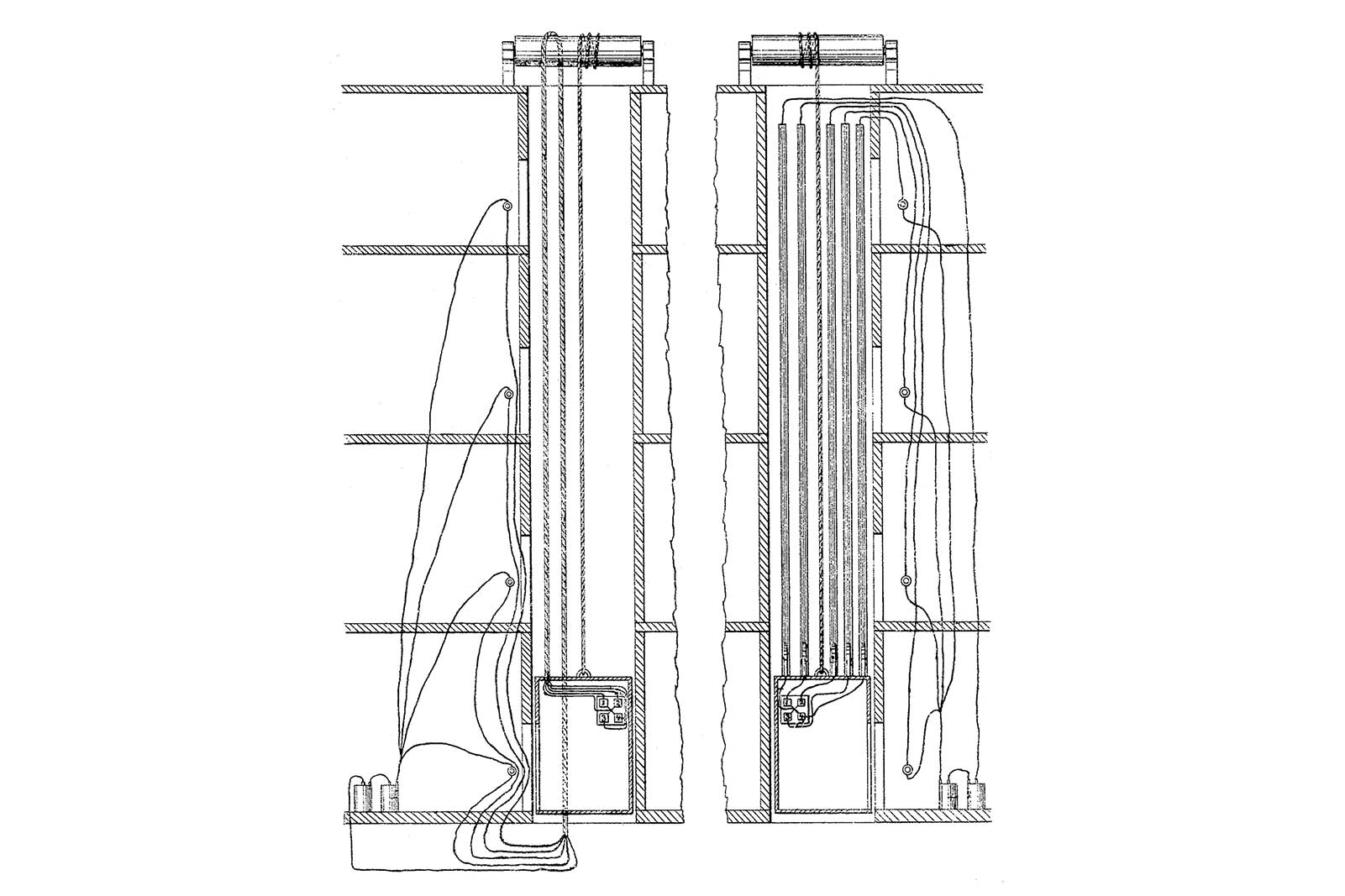

By the early 1870s two solutions had emerged that addressed the challenge of maintaining contact between the moving car, the hall-call buttons and the system’s power source:

“One by means of a flexible cable of insulated wires, which was attached to the car with sufficient slack to allow the car to pass up and down the elevator well — this is called the flexible cable method; and the other by means of wires suspended upon or against the side or wall of the well, and with which wires projecting from the car and connected with the annunciator were kept in contact as the car passed up and down the elevator well — this latter is called the sliding or friction contact method.”[2]

Elisha Gray (1835-1901) was the first to devise a system predicated on the sliding or friction contact method. This occurred between late 1870 and March 1, 1871, during which time Gray “constructed and put in operation an electric annunciator in the elevator” in the Palmer House Hotel in Chicago.[2] That same year, Edwin T. Holmes (1820-1901) installed an annunciator in the Parker House Hotel in Boston that employed the flexible cable method. In his autobiography Holmes stated:

“The question arose, why cannot an annunciator be placed in a moving elevator, and be connected by wire with each floor? The necessary lengths of copper wire were drawn into a rubber garden hose and the elevator annunciator was introduced, this being not only as novel but even more wonderful than anything previously done.”[3]

By 1872, Holmes had installed elevator annunciators in the Nicholas Hotel and Hoffman House Hotel in NYC, and the Ebbitt House Hotel in Washington, D.C. During this same year, Holmes clearly articulated the purpose and advantages of this new communication system:

“We have also invented and patented an electric annunciator for an elevator, which is placed on the car of the elevator, and so arranged that the guests on each floor can announce to the operator in the car where they stand waiting to be moved. This affords a greater and quicker accommodation to guests, and saves time and expense in making regular trips, as the car stands still until the operator is notified by this telegraph that he is wanted at a certain place.”

This system apparently allowed the car to remain parked at the lobby, thus making it readily available to arriving guests, while also serving the needs of guests staying on a hotel’s upper floors.

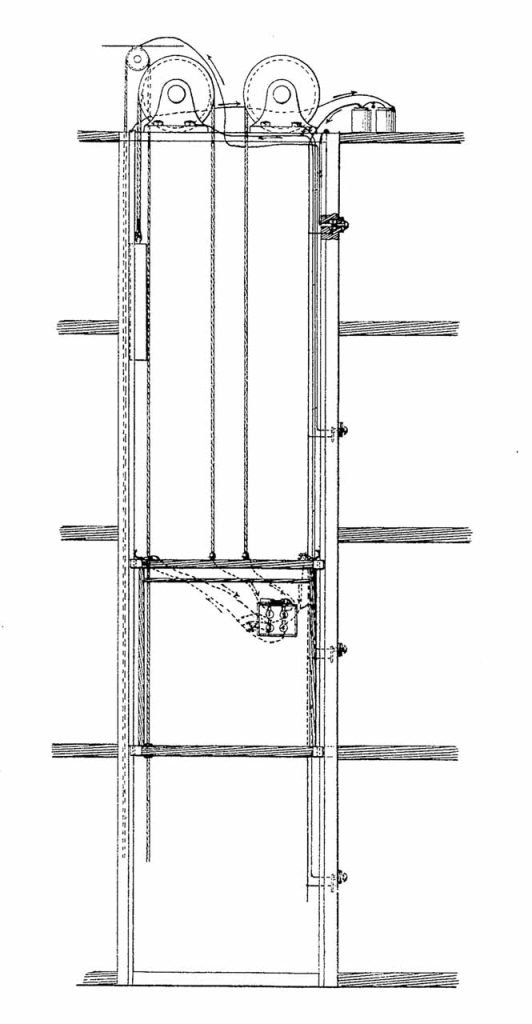

The core industry products of the 1880s primarily derived from four patents dating from the early 1870s: Edwin Holmes, Improvement in Electric Indicator for Elevators, U.S. Patent 121,620 (application date unknown, patent awarded December 5, 1871); James H. Corey, Improvement in Electrical Indicators for Elevators, U.S. Patent 137,422 (application date November 14, 1872; patent awarded April 1, 1873); Augustus Hahl, Improvement in Electric Indicators for Elevators, U.S. Patent 148,447 (application date February 7, 1872, patent awarded March 10, 1874); and Gray, Improvement in Electric Annunciators for Elevators, U.S. Patent 172,993 (application date February 3, 1873; patent awarded February 1, 1876). The Holmes and Corey patents addressed sliding or friction contact systems (Holmes’ patent focus was surprising given his early use of the flexible cable system); the Hahl patent addressed both sliding or friction contact and flexible cable systems; and the Gray patent addressed a flexible cable system (Figures 1 – 4). These patents were the subjects of numerous lawsuits, with the final resolution reached in December 1882:

“While the Hahl application was pending in the patent office, interferences were declared between his device and pending applications for, substantially, the same thing by Edwin Holmes and James H. Corey, which resulted in a decision by the commissioner in favor of Hahl as the first inventor as against both Holmes and Corey, and the patent was issued to Hahl, dated March 10, 1874. After the patent had been issued to Hahl an interference was declared between the applications of Gray, which had been filed in February, 1873, and Hahl, and pending this interference, after proofs had been taken, concessions were made between Gray and Hahl by which Hahl admitted Gray to be the prior and first inventor of the device contained and claimed in the first claim of the Gray patent, and Gray conceded to Hahl priority of invention of the flexible cable method of connecting the annunciator in the car with the signal keys and battery; the proof showing that although Gray may have conceived the idea of the flexible cable method prior to Hahl, yet Hahl was the first to embody that idea in a working mechanism, as well as the first to apply for a patent thereon.”[2]

By 1882, the rights to the Gray and Hahl patents had been acquired by the Western Electric Co. of Chicago.

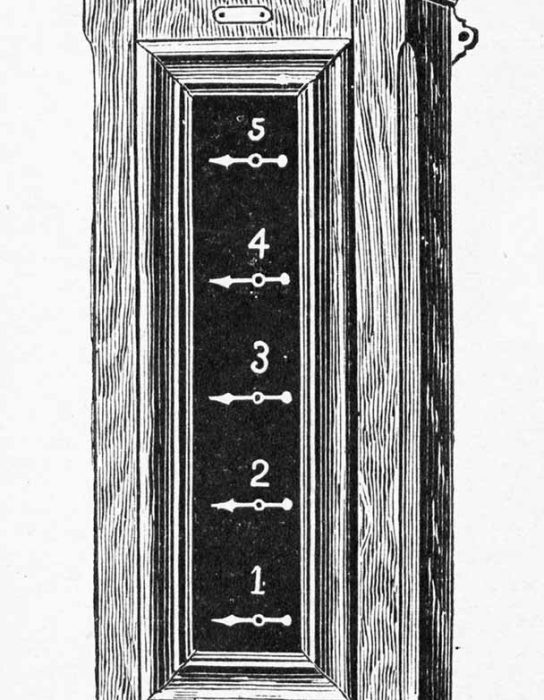

Founded as the Western Electric Manufacturing Co. in 1869 by Gray and Enos Barton, the company quickly became a leading manufacturer of a wide variety of building communication systems, including an early version of the telephone developed by Gray in 1876. The company was purchased by the American Bell Telephone Co. in 1881 (Bell was the predecessor to the company that later became AT&T), and the name was changed to the Western Electric Co. The design of the company’s elevator annunciator followed a pattern employed by other manufacturers. Single call buttons were located adjacent to the elevator doors. While the buttons allowed waiting passengers to signal the operator that a car was needed at a given floor, the signal did not indicate the desired direction of travel. The car was equipped with a vertical annunciator panel that featured floor numbers and a horizontal arrow located beneath each number (Figure 5). When a floor hall-call button was pushed, the arrow tilted upward, indicating the need for a stop. The operator “cleared” the annunciator by pulling on the knob at the bottom of the panel. By the late 1880s many systems had added “up” and “down” hall-call buttons and employed two annunciator panels in the car, one for each direction of travel.

The proliferation of flexible cable systems was such that standard installation guidelines were in place by the mid-1880s:

“Care must be taken to have the cable swing freely so that the cab will not interfere with it. Some slack must be left too, so that when the elevator is clear to the top or bottom of the well the cable will not be pulled tight. The usual method is to suspend one end of the cable midway between the top and bottom of the elevator well and run the other end of the cable to the bottom of the cab, fastening each end securely and then splicing the wires on to the conductors of the cable. The battery is usually placed in the basement, and the wires run along one side of the well from the end of the cable to the battery and push buttons.”[5]

The typical cost of adding annunciators to a VT system is indicated by a Western Electric price list from the late 1880s.[6] The total cost included the car annunciators and cables. Annunciator costs were predicated on the number of floors served, for example: a three-floor annunciator cost US$10 per car; annunciators that served six or more floors cost US$25 per car. Depending on the number of floors served, cable prices ranged from 30 to 45 cents per foot.

The companies identified thus far that manufactured elevator annunciator systems included businesses that varied in size and commercial presence: Seth W. Fuller (Boston), Hinds & Pope (Boston), Kendall Manufacturing Co. (Boston), Goodrich and Hoover (Buffalo), American Electric Manufacturing Co. (Chicago), Western Electric Co. (Chicago, New York, London, Antwerp), H.D. Rogers & Co. (Cincinnati), E.T. Holmes & Co. (New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and Cincinnati), Edward C. Bradley (Rochester), C.A. Cummings (Worcester, Massachusetts), Frank W. Wheeler (Worcester, Massachusetts) and Reed & Page (Worcester, Massachusetts). While evidence exists that suggests that these companies supplied the majority of elevator annunciators manufactured during this initial phase of the VT industry’s maturity, missing from the story is the possible role played by VT companies in providing these systems, as well as the possibility of direct commercial ties between specific VT and annunciator manufacturers. Future articles will explore the continued development of allied industries that supplied critical VT industry components, as well as subsequent phases of the VT industry’s development, including Otis’ consolidation efforts in the 1890s, the rise of Westinghouse in the early 20th century and the emergence of regional and national firms in the 1940s and 1950s.

References

[1] Advertisement for E.T. Holmes & Co. (New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and Cincinnati), The Boston City Directory … for the Year Commencing July 1, 1872, Boston: Sampson, Davenport, & Company (1872).

[2] Western Electric Manufacturing Co. v. Chicago Electric Manufacturing Co., Circuit Court, N.D. Illinois (December 26, 1882).

[3] Edwin T. Holmes, A Wonderful Fifty Years, Privately Published (1917).

[4] Charles Edwin Prescott, Ed., The Hotel Guests’ Guide to the City of New York, Second Edition, New York: Geo. W. Averell, Publisher (1872).

[5] Francis B. Badt, Bell Hangers’ Handbook, First Edition, Chicago: Electrician Publishing Co. (1888).

[6] Condensed Price List of the Western Electric Co., Chicago, New York, London, Antwerp. (July 1889).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.