ELEVATOR WORLD, 1966

Apr 1, 2016

A commitment to innovation has a parallel after 50 years.

The history of the vertical-transportation industry is, in many ways, the story of repeated attempts to solve a basic set of problems, which may be summarized under the broad headings of passenger safety, mechanical operation and efficiency (though these, admittedly, cover a broad range of related issues). An examination of ELEVATOR WORLD in 1966 serves as a reminder that, 50 years ago, when new skyscraper typologies and innovative manufacturing techniques were emerging, the vertical-transportation industry sustained its focus on providing solutions to this basic set of problems. This steadfast pursuit also embodied another consistent characteristic of this unique history: a commitment to innovation.

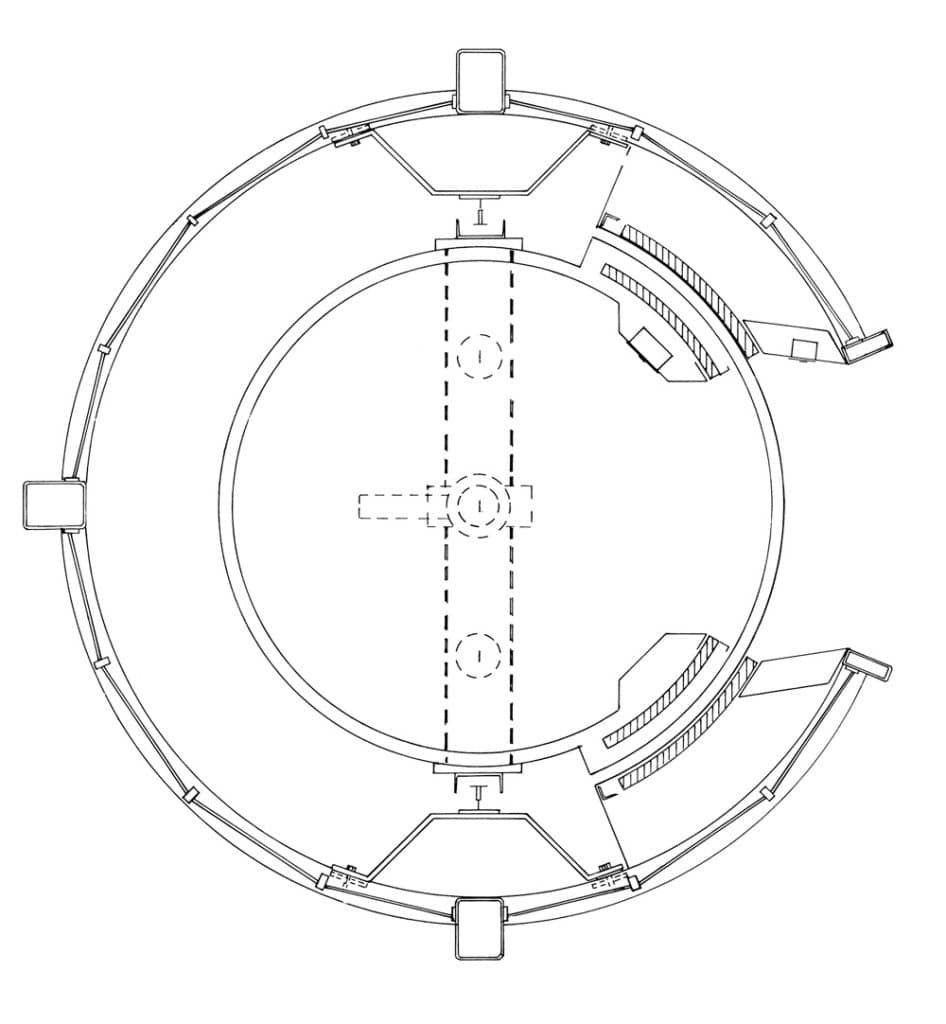

The February issue included an illustrated article on a recently completed glass elevator installed in Hughes, Hatcher, and Suffrin — a men’s clothing store located in Detroit. The elevator’s setting was a new two-story store designed by Copeland, Novak, and Israel (New York), working in collaboration with Louis Redstone Co. (Detroit). The elevator appears to have been primarily designed by the architects, who worked in collaboration with Dover Elevator Corp. and Cambridge Cars (a manufacturer of custom elevator cars). The glass was furnished by Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co., and the door operator was manufactured by G.A.L. Electro-Mechanical Service.

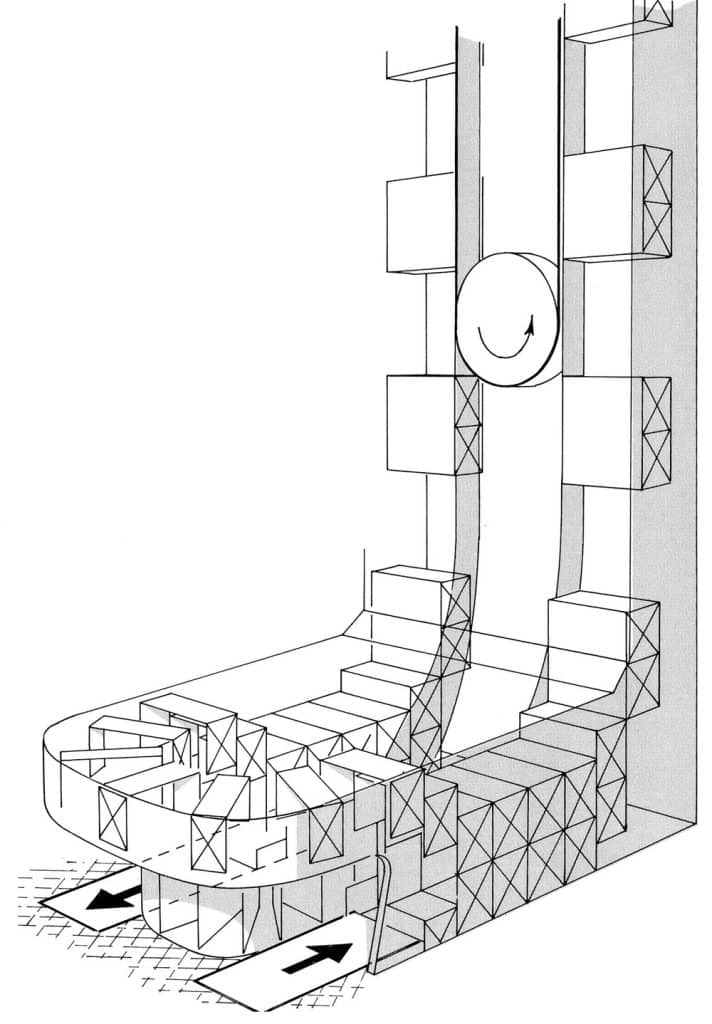

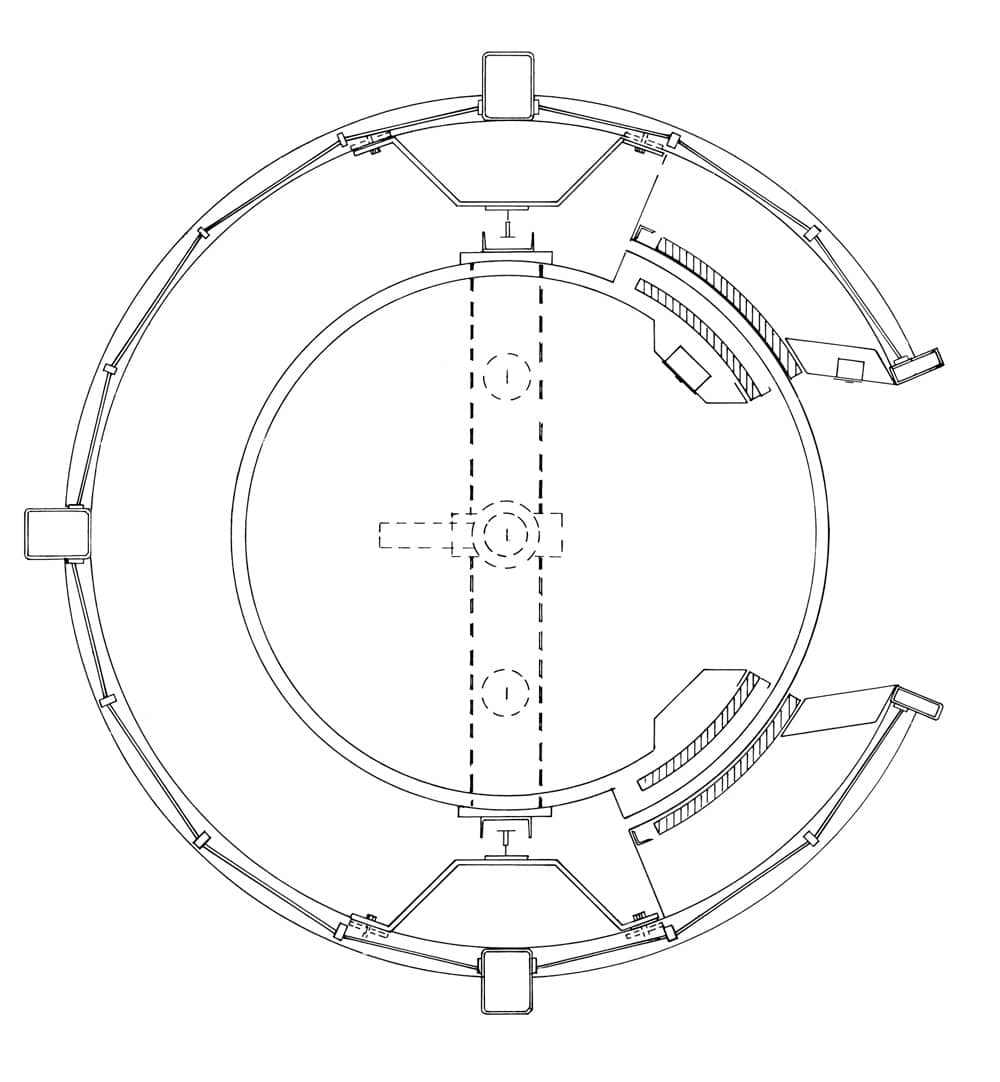

The elevator was a piston-actuated hydraulic machine located in the center of a large spiral staircase. The 12-passenger circular car featured walls composed of six 84-in.-high curving glass panels, which were supported by a decorative wrought-iron frame. The shaft employed a simple aesthetic and featured 12 flat glass panels that provided a gentle faceted appearance. The article reported, “A problem presented by the all-glass hoistway was that of concealing the traveling cables leading to and from [the] door interlocks, call buttons and the control room.” While the solution to this problem was not fully discussed or revealed, the article’s accompanying images illustrated the elegant final result (Figures 1 and 2).

The use of glass was also addressed in the April issue; however, the context was an overview of the revised edition of the American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters, Escalators, and Moving Sidewalks (Figure 3). This seventh edition of the A17.1 code had been published in late 1965, and the author of the EW article was William C. Crager, chairman of the American Standards Association Sectional Committee A17 and Superintendent of the Loss Prevention and Engineering Department of Royal Globe Insurance Cos. The revised code included “more than 125 revisions to the 1960 code,” which addressed changes required due to passenger use (and abuse) of elevators, outdated operational technologies and the innovative use of materials. Crager reported that the activities of a particular passenger group prompted one important revision:

“In recent years, children’s mischievous practice of gaining access to elevator car tops through top emergency-exit openings from inside cars in apartment houses has resulted in many serious injuries and, in some instances, fatalities. To minimize this unanticipated exposure, a code revision requires that top exit covers be openable only from the top of the car.”

The increased height of skyscrapers and other operational changes resulted in revised standards for elevator cables:

“A previous requirement that wire ropes employed as suspension means have fiber cores, has been deleted from the code to keep pace with developments in the elevator and rope industries. Originally, the wire-rope industry made wire ropes with fiber cores for all applications. Later, as heavier pressures were encountered in some applications, fiber cores were unable to support the steel strands in their proper position, and steel cores were introduced.”

Code revisions also continued to address the rapid growth of escalator use. These included new standards for the width of step treads and the approval of all glass side panels: “The use of shatterproof glass (which is also considered a safety glass), as well as tempered glass, is now permitted in balustrade panels” (Figure 4).

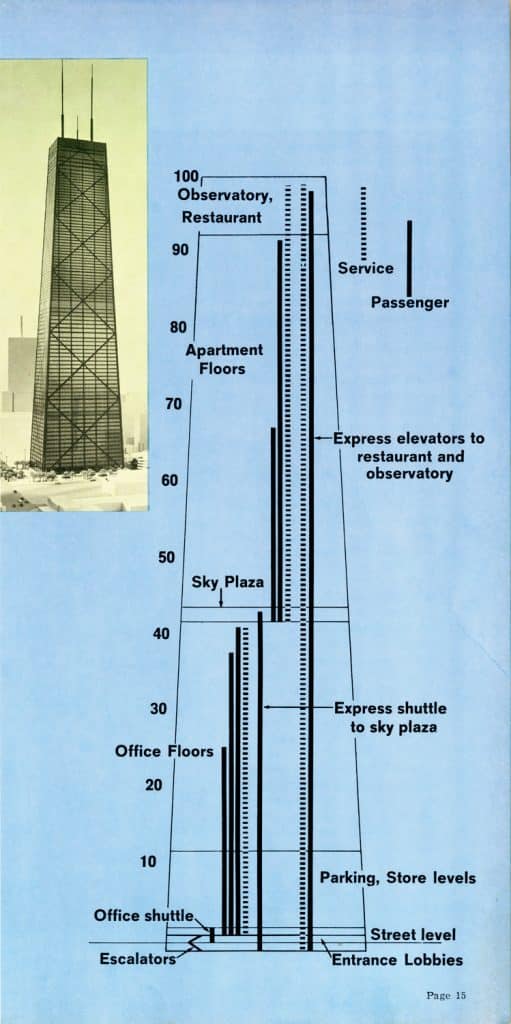

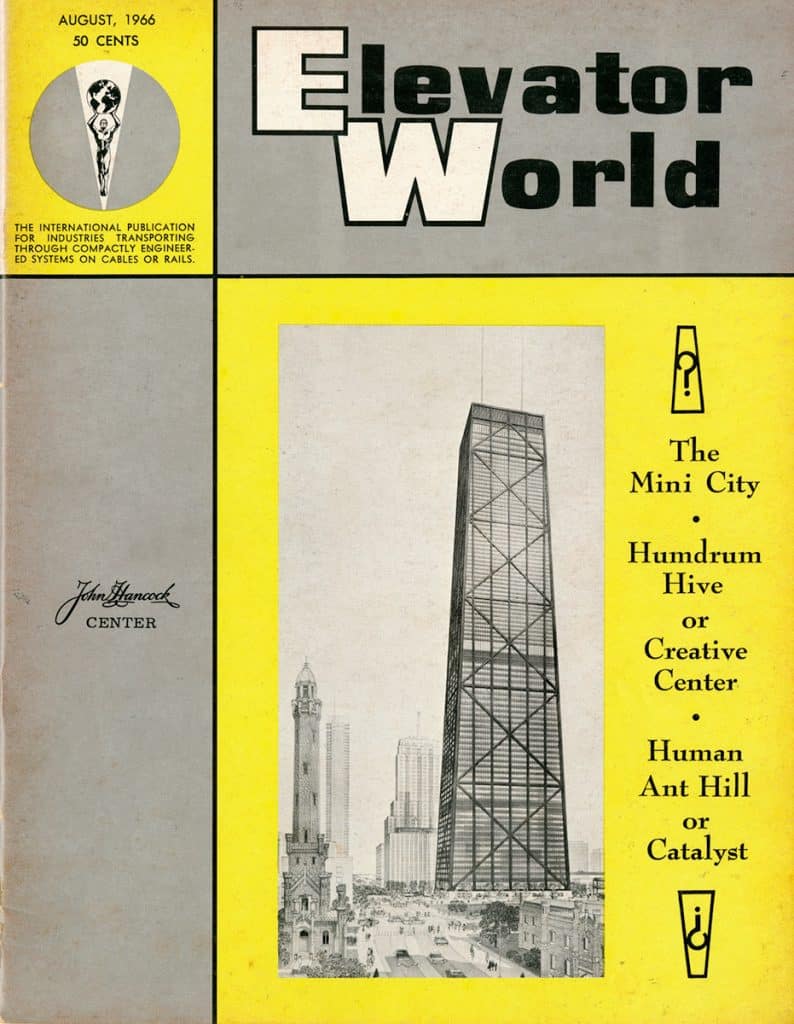

The August cover article focused on Chicago’s John Hancock Center. Construction had started in June 1965, and by mid 1966, the tower’s innovative mixed-use program (apartments, offices, commercial spaces and parking), structural system and proposed height (100 stories: 456.9 m [1,499 ft.]) made it one of the most talked-about buildings in the U.S. Eventually completed in 1969, the building was to be equipped with 50 Otis “electronically controlled elevators,” which included the world’s fastest elevator, operating at 1,800 fpm. Eugene D. “Ed” Hull (1920-2014), Otis vice-president, Middle Western Region, claimed the building marked a “milestone in commercial elevator installation” and provided the industry with “a unique showcase where technological advances can be made applicable to multipurpose elevator travel under one roof.” A critical aspect of the system was the presence of the first sky lobby (identified as a “sky plaza” in the elevatoring diagram) that served as the transition point between the office and apartment sections of the building (Figure 5). While William C. Sturgeon, EW founder and editor at the time, recognized that this new skyscraper typology created “a huge new market” for equipment, he also expressed concerns about a building that, in theory, would allow residents to live, work and play within the confines of a single building. Sturgeon articulated these concerns in his monthly editorial column, “Speaking of Issues,” and on the magazine’s cover page (Figure 6).

The August issue also contained an article originally published in the January 1966 issue of Science Journal (London). Titled “Continuous Lifts for High Buildings,” it described an elevator system designed by Gabriel Bouladon and Paul Zuppiger, researchers associated with the Battelle Memorial Institute in Geneva. The inventors characterized the current state of vertical transportation as follows:

“Of the two means of vertical transportation available, the elevator is a discontinuous system, but it does have the advantage of being able to move at relatively high speeds — up to about 25 fps. However, its efficiency — measured in persons per minute — falls off with height of the building. The escalator, on the other hand, is a continuous system, and an installation carrying two passengers abreast can deliver 120 persons per minute. Its disadvantage is that it has to operate at a speed of about 2 fps to enable passengers to step on and off without difficulty. This factor limits the use of escalators to only three or four stories.”

Bouladon and Zuppiger perceived their design as combining “the advantages of both lift and escalator without their disadvantages” and claimed their continuous elevator offered “the output of an escalator and the speed of an elevator” (Figure 7). Its proposed operation was described as follows:

“As a passenger prepares to step onto it, the continuous elevator resembles a conventional escalator. It then changes, by a gradual closing of doors between steps, into a series of elevators. By accelerating vertically, the elevator cabins move into position one above the other before ascending or descending at high speed in a vertical shaft. The reverse process decelerates the cabins and allows passengers to alight as from an ordinary escalator.”

Adjacent to the reprinted article was a critique written by A.D. Ryder, managing director of Wm. Wadsworth & Sons, Ltd. (Bolton). Ryder noted that Bouladon and Zuppiger’s system only moved passengers “between two points” and made no provision for stops at intermediate floors. He also questioned the safety of employing “gradually closing doors, which would apparently be coming down on all four sides.” Finally, he observed with characteristic British tact, “Other less obvious problems come to mind, but the difficulties I have mentioned seem so elemental that one is lead to wonder. . . whether the Battelle Memorial Institute are really using their funds to the best advantage.”

The October 1966 Annual Issue was titled “Looking into the Future” and was part two of EW’s “Packages in the Sky” series. Part one, published in the October 1965 Annual Issue, addressed issues associated with “Systems Building,” and Part II was devoted to “packaged,” or preassembled, systems (Figure 8). The editorial content included articles on escalators, moving walks, shafts and penthouses. The escalator article reported that “pioneering” work in this field had “primarily” been accomplished by firms outside the U.S. The first escalator with glass balustrades “originated in Japan,” and the “longest and fastest escalators” to date had “been installed in Europe.” A critical aspect of these systems was the design and production of “packaged equipment.” A packaged escalator was defined as “a continuous lift, self-contained in its structural-steel hatchway.” The escalator was built as “a one-piece unit,” with the side trusses first “assembled and brought together to form a staunch container. Thereafter, the mechanical and electrical equipment is installed within the framework, and a skin of paneling and balustrade provided.”

The article on shafts addressed a variety of current approaches aimed at providing “a stack of vertically operating equipment with substantial or total integration.” These approaches featured discrete efforts, such as factory installation of control and floor wiring, wiring within doorframes and the development of wiring stacks that contained the car-top controls, junction box and cabin control panel. Other initiatives focused on the development of prefabricated shafts. These efforts ranged from the use of non-elevator companies to build precast concrete shaft sections (typically one floor in height) to the production of shaft sections by elevator manufacturers. The latter efforts included prefabricated shaft systems designed to facilitate the installation of all equipment on the jobsite, as well as attempts to achieve the total integration of shaft and equipment in the factory.

The issue’s European editorial bias is evident on every page and is expressed in the text, images and featured companies, which included the following:

- A.K. Gebauer & Cie. (Switzerland)

- Ascinter-Otis (France)

- Express Lift Co., Ltd. (England)

- Hiss AB ASEA-Graham (Sweden)

- Kleeman’s Vereinigte Fabriken (Germany)

- KONE (Finland)

- Marryat & Scott, Ltd. (England)

- Orenstein-Koppel und Lubecker Maschinenbau AG (Germany)

- Otis-Holland (Netherlands)

- Thrige-Titan Elevator Co. (Denmark)

- SABIEM (Italy)

- Sandvikens Jernverk AB (Sweden)

- Schindler & Cie. (Switzerland)

- Stigler-Otis S.P.A. (Italy)

- Wertheim-Werke (Austria)

The absence of American firms was striking and, in fact, informed Sturgeon’s assessment of the state of the industry in 1966:

“The challenge to the U.S. elevator industry — and, naturally, that is the primary one we address ourselves to — is to conscientiously explore the missing “third” ingredient — preassembly. Modelization is well in hand throughout the country, and the system of specialty suppliers seems to be strengthening each year. What remains is to form a committee of imaginative people from the manufacturer, contractor and union groups to study, for several years, the possibilities and implications of preassembly. At the end of that time, the recommendation may be that the status quo must be observed. If so, at least the decision to do nothing would be made upon factual evidence that rationalization of the U.S. elevator industry would be harmful in certain areas. On the other hand, it might become apparent to all concerned that there is great merit in effecting a new ‘way of life’ in the industry. A renaissance would then take place in the American elevator industry.”

A question, perhaps worth asking 50 years later, is: has the renaissance occurred, or are we still waiting?

Figure 1: “Plan, Glass Elevator,” Hughes, Hatcher, and Suffrin (Detroit) (EW, February 1966)

Figure 2: “Glass Elevator,” Hughes, Hatcher, and Suffrin (Detroit) (EW, February 1966)

Figure 3: Cover, American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters, Escalators, and Moving Sidewalks (1965)

Figure 4: Escalator with glass balustrades (EW, August 1966)

Figure 5: “Elevatoring Diagram,” John Hancock Center (Chicago) (EW, August 1966)

Figure 6: Cover, EW, August 1966

Figure 7: Gabriel Bouladon and Paul Zuppiger, “Continuous Lift for High Buildings,” (EW, August 1966)

Figure 8: Cover and Table of Contents, EW, October 1966

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.