Fred A. Annett’s Electric Elevators (1927) Conclusion

May 1, 2024

A look at contributions made to the book

In the introduction to Electric Elevators: Their Design, Construction, Operation and Maintenance by Fred A. Annett (published by McGraw-Hill in 1927), the author acknowledged that “most” of the book’s material had appeared, “at various times,” in the engineering magazine Power.[1] Annett also noted that, while the book “in the most part has been written by the author and appeared under his name,” it was important that he express “his appreciation” to others “for their assistance in the preparation” of the book. The list of individuals cited reveals the breadth and depth of Annett’s association with the American vertical-transportation industry: Mortimer A. Meyers, the Maintenance Co., NYC; William Zepernick, Otis Elevator Co., Chicago; Howard B. Cook, Warner Elevator Manufacturing Co., Cincinnati; Warren Hilleary, Royal Indemnity Co., NYC; Jacob Gintz Jr., New York Electrical School, NYC; Clarence R. Calloway, Gurney Elevator Co., NYC; W.F. Glasier, Cutler-Hammer Manufacturing Co., NYC; Adolph A. Gazda, Kaestner & Hecht Co., Chicago; Ernest B. Thurston, Haughton Elevator & Machine Co., Toledo; Edgar M. Bouton, Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co., Pittsburgh; and Frank E. Lewis, Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co., Pittsburgh.

In the text, Annett appeared to carefully cite the contributions of his collaborators with the citations reflecting the nature of the individual contribution. In Chapter 3, Methods of Roping and Their Effects on Loading of the Cables and Bearings, he noted, “The material on compensating cables was written by A. A. Gazda.” Chapter 4, Overspeed Governors and Car Safeties, included a note that “M. A. Myers … and Howard B. Cook … supplied a large part of the material in this chapter.” Chapter 5, Thrust Bearings and Their Adjustment, included an acknowledgement that “M. A. Myers … supplied a large part of the material in this chapter.” Chapter 7, Alternating Current Brakes: Their Care and Adjustment, offered a variation on this theme: “Howard B. Cook … assisted in the writing of this chapter.” Chapter 13, Direct Current High Speed Traction Machine Controllers, echoed the statement found in Chapter 4: “Warren Hilleary … and William Zepernick … supplied a large part of the material in this chapter;” as did Chapter 17, Single Speed Controllers for Alternating Current Slip Ring Motors: “William Zepernick … supplied a large part of the material in this chapter.” Lastly, Chapter 24, Cables, Their Construction and Care, included a note regarding elevator usage data featured in the chapter: “These records are due to Captain M.W. McIntyre, Manager, and C.B. Garrison, Chief Engineer, of the building referred to, and were published in Power, July 24, 1923.”

Annett, however, failed to cite all of his collaborators’ contributions. He omitted a citation noting that Zepernick had also contributed material to Chapter 6, Direct Current Brakes: Their Care and Adjustment. And, somewhat surprisingly, he failed to reference the fact that Jacob Gintz Jr. contributed substantial material for Chapter 10, Direct Current Semi-Magnetic Controllers, and Chapter 11, Two Speed Direct Current Motor Controllers. Gintz was an instructor at the New York Electrical School; prior to joining Power in 1916 as an associate editor, Annett had also been on the school’s faculty. He also failed to note that Ernest B. Thurston made a contribution to Chapter 7.

Thus, nine of the book’s 25 chapters included material by Annett’s collaborators. Knowing this, a reasonable question is: What exactly did they contribute? And what, precisely, did comments such as “supplied a large part of the material” mean? Given that Annett acknowledged that most of the book’s material had previously appeared in Power, a survey of its contents from 1916 (the year he joined the magazine) to June 1927 (the book was published in July) was undertaken. This survey revealed that his collaborators authored a total of 17 articles during this period that provided material for the book. A comparison of the articles’ contents (text and images) to the book’s contents revealed that most of the articles were republished in full with very minor (if any) edits. For example, Chapter 4 was entirely composed of three articles, which were arranged by Annett to cover the material in a specific sequence: Myers, “Electric Elevator Machinery – Overspeed Governors” (July 12, 1921), Cook, “Operation of Over-Speed Governors on Electric Elevators” (October 23, 1923), and Myers, “Electric Elevator Machinery – Car Safeties” (August 2, 1921). The article publication dates suggest that Annett was more interested in structuring the material to present a coherent narrative than following a strict chronological order.

The results of the search for his collaborators’ contributions prompted another, perhaps equally obvious question: How many articles by Annett appeared in the book? The answer is surprising. Only nine articles by Annett (one of which was coauthored with Cook) were republished in the book: six articles appeared in Chapter 1, Types of Machines – Direct Current Equipment, the coauthored article appeared in Chapter 7 and two articles appeared in Chapter 25, Replacing Cables on Elevator Machines.

This would appear to imply that the remainder of the text was composed of new material written exclusively for the book. This assumption is incorrect. Most of the remaining 14 chapters were primarily composed of republished Power articles written by Charles A. Armstrong, who contributed a total of 21 articles to the book. Given the scale of Armstrong’s contributions, it is curious that Annett did not acknowledge his presence. However, a careful re-reading of the introduction coupled with some educated guesswork yields the answer to this mystery. Annett had told his readers that the book “in the most part has been written by the author and appeared under his name or a nom de plume.” Charles A. Armstrong was one of several pen names used by Annett during his career with Power.

The survey of Annett’s use of the Power articles revealed that only one of 25 chapters was apparently written directly for the book: Chapter 2, Alternating Current Machines. The remaining 24 chapters were comprised of material drawn from 62 previously published articles, most of which were republished in full with only minor edits and/or limited additional material.

In assembling the book, Annett had a wealth of material to draw from: between 1916 and June 1927, Power published 159 articles and news items on electric elevator technology and operation. He exercised his editorial skills in selecting which articles to include and how they would be utilized to construct a coherent narrative. The book’s 25 chapters focused on four basic content areas: direct current machines (eight chapters), alternating current machines (six chapters), components and systems common to both types of machines (eight chapters) and roping (three chapters). The chapters devoted to direct and alternating current machines addressed motors, brakes, controllers and operational problem solving (which Annett referred to as “locating faults”). The general systems chapters covered over-speed governors, car safeties, thrust bearings, reversing switches, variable voltage controllers, push button control and lubrication. The chapters on roping addressed the construction and care of ropes, methods of roping and replacing ropes.

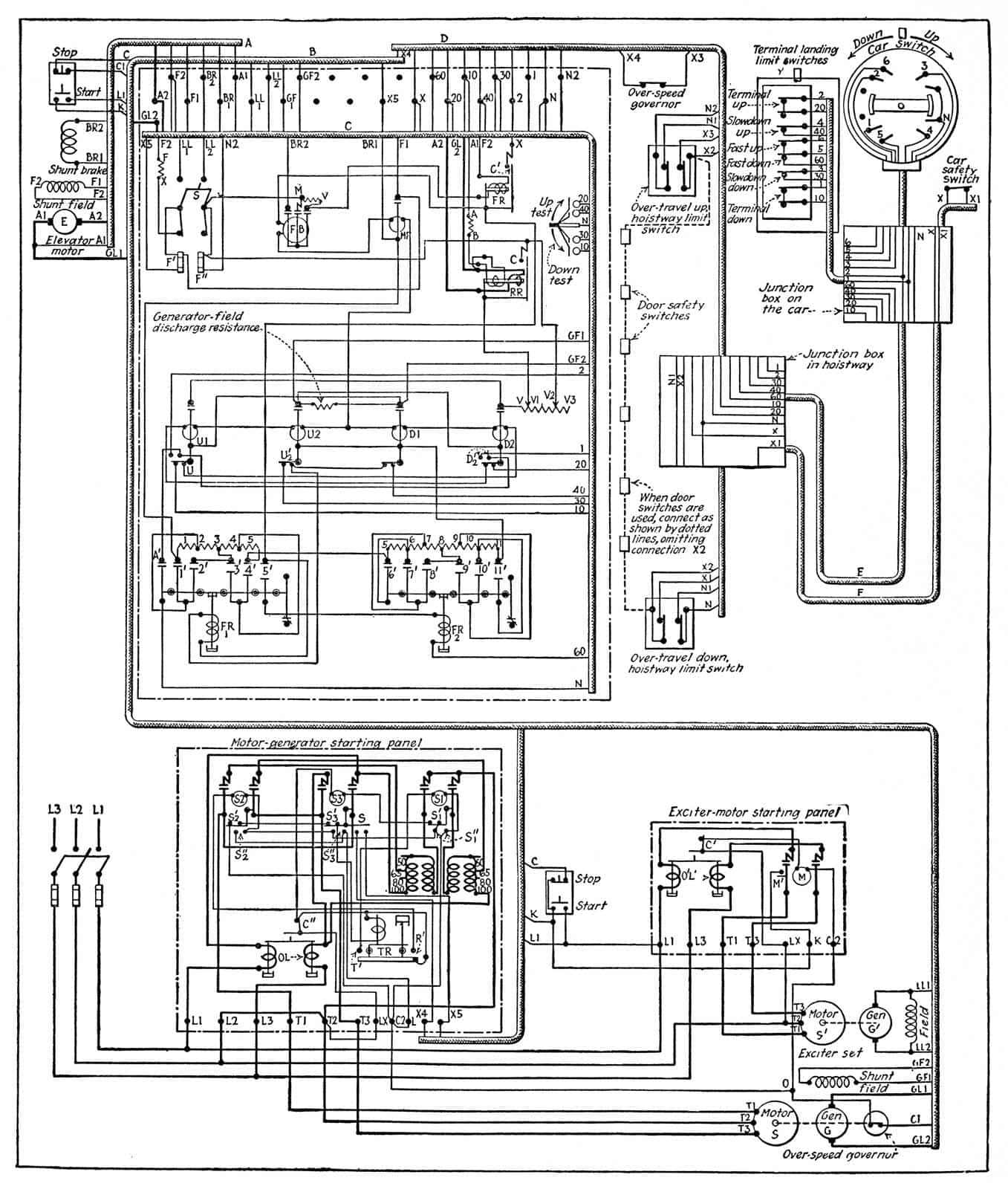

While the book does serve as an effective introduction to elevator technology, the primary audience was not students but VT professionals working in the field and individuals charged with daily maintenance. This was reflected in the book’s text and illustrations. The latter featured 160 photographs, 104 drawings and 87 wiring diagrams. The wiring diagrams ranged from schematic diagrams of basic components to detailed diagrams of specific controllers. The majority of the drawings addressed various aspects of roping. And, lastly, the photographs covered a wide array of subjects from complete elevator machines to individual components.

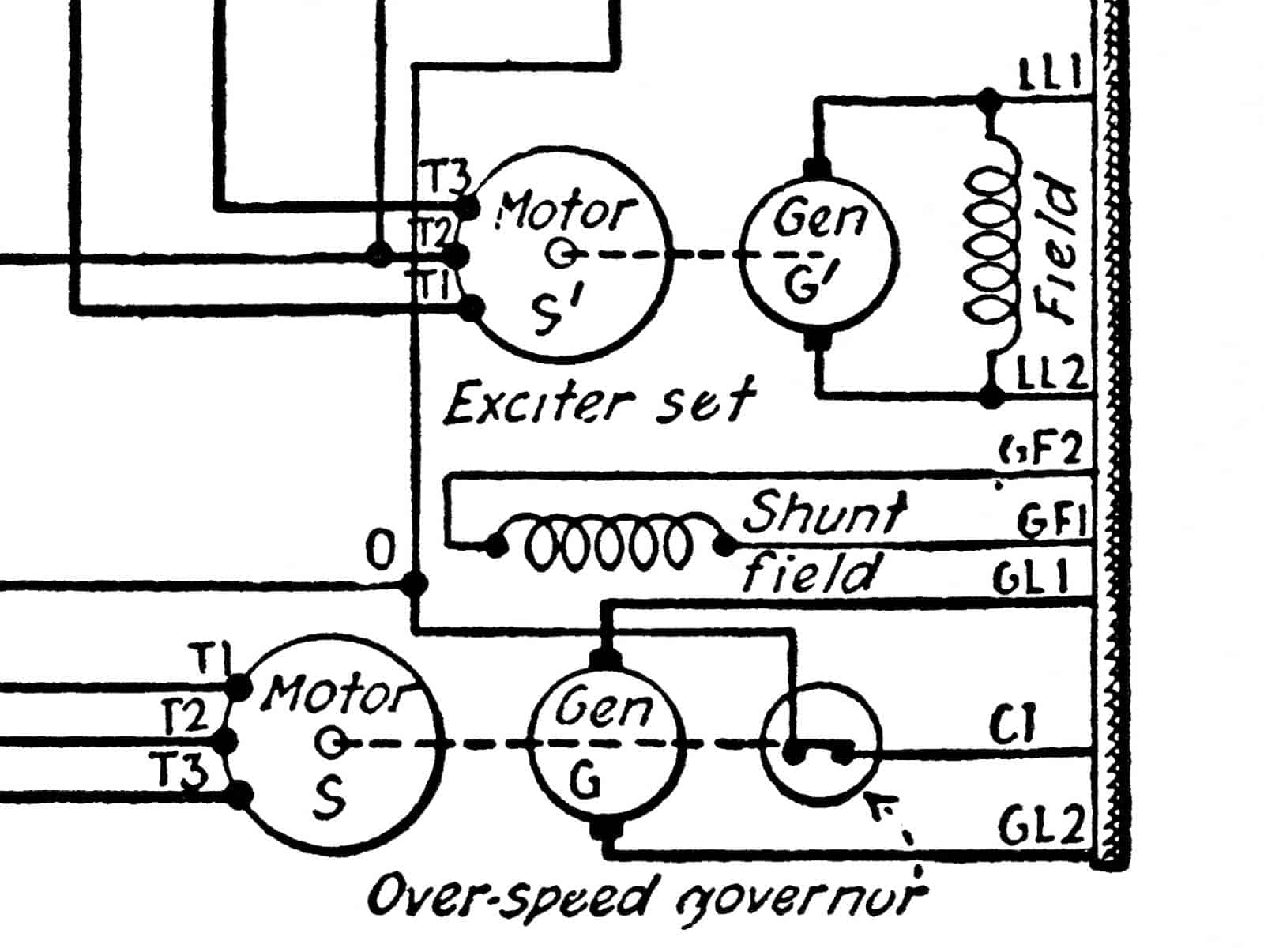

The various images played an integral role in the book and were used strategically to help the reader understand a given topic. This reflected the editorial approach found in Power. This approach may be illustrated by an excerpt from the chapter on variable voltage controllers, which began with an introduction to these systems accompanied by a drawing of a complete system wiring diagram and a photograph of a typical controller (Figures 1-3):

“Where alternating current is available, a squirrel-cage motor is used to drive the generator. For direct current supply a shunt-wound motor drives the generator. In all cases, the motor and generator should be designed for the service. The motor should have good speed regulation and high efficiency, while the generator must be so designed that its voltage will respond quickly to changes in field current, or the operation of the elevator will be sluggish. Its efficiency should be high in order to keep the power losses to a minimum. Figure 229 shows the elevator control panel and Figure 230 a connection diagram for a Cutler-Hammer variable-voltage controller for a traction elevator, with the power supplied from an alternating current system. A squirrel cage motor S driving a direct current generator G furnishes the power to the elevator motor E. This generator has its fields excited from a second motor-generator set consisting of a small squirrel-cage motor S’ and a shunt generator G’. The object of the separate exciter is to insure the excitation of the generator supplying power to the elevator motor and to make the voltage of the generator respond more quickly to the control and consequently the speed of the elevator motor.”

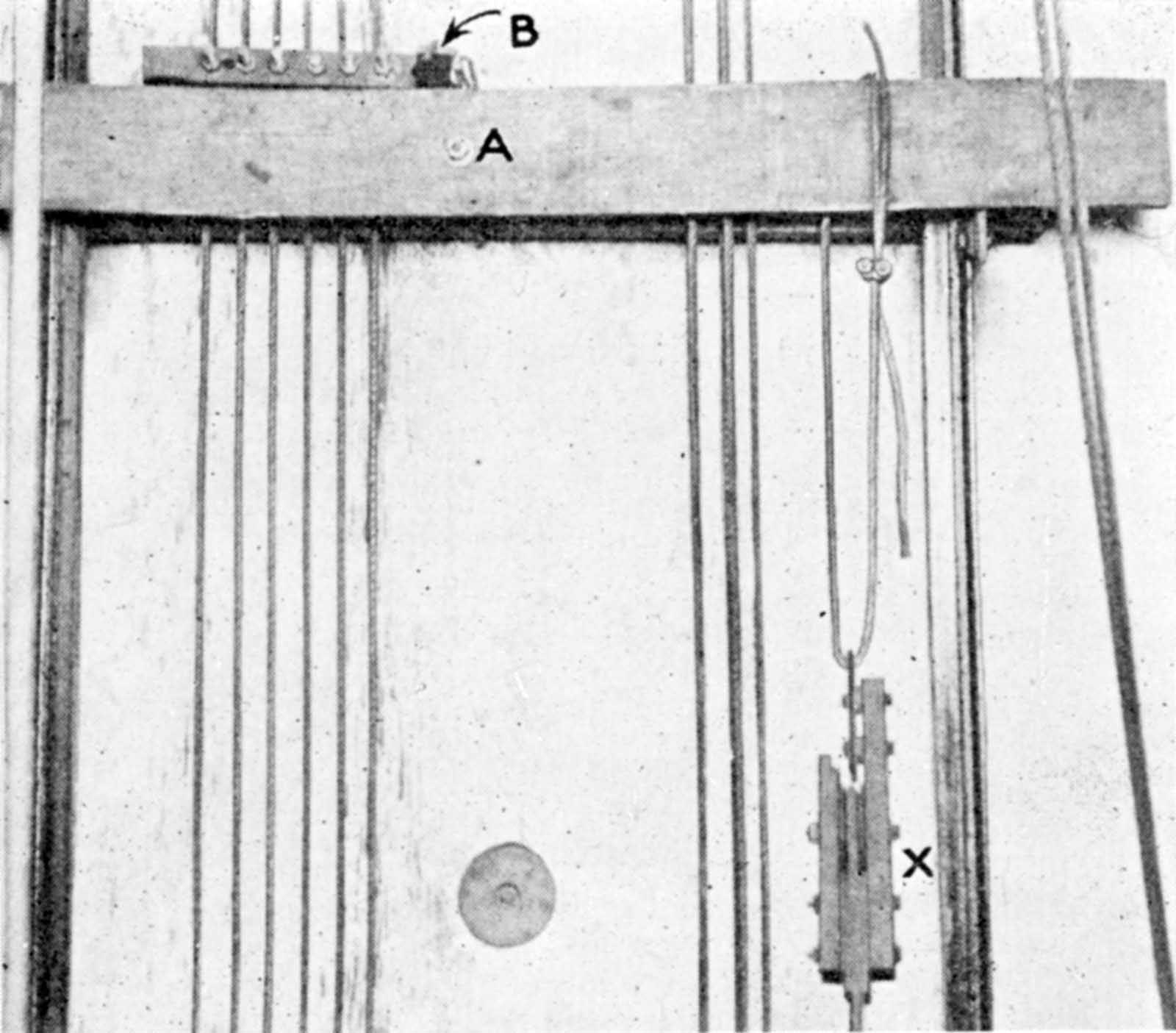

This introduction was followed by a detailed description of the controller’s operation. Another example of the practicality and clarity of presentations in the book is illustrated by two images from Chapter 25. The first image is a photograph of a rope replacement in progress, and the second is a perspective drawing of the same operation (Figures 4 and 5). In these images, “A” indicates the location of two planks “placed across the counter-weight guide rails above the top of the car … (which) rest on the guide-rail supporting brackets, one plank on each side of the rails, held together by one bolt.” “B” is a rope-clamping device, and “X” is a “sheave is used to support the cables when they are being run on. On the long side of this pulley is bolted a piece of iron to support it in the elevator shaft.” These figures were accompanied by eight additional images and a complete description of the rope replacement process.

Annett concluded his introduction by acknowledging that his book was “not as complete as might be desired.” However, any failings the book might have had resulted from “the demand for a work on modern elevators,” which “made it appear advisable to make this information available rather than delay the publication until a more comprehensive work can be prepared.” In other words, McGraw Hill was anxious to publish the book as quickly as possible, a fact that explains the minimal editing of the republished articles. Annett also noted that the “rapid development in the art will undoubtedly justify a revised edition in a few years.” The revised edition appeared in 1935 and will be the subject of a future article.

Reference

[1] Annett, Fred A. Electric Elevators: Their Design, Construction, Operation and Maintenance. 1st Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1927. Note: All quotations derive from this source.

Also read: Fred A. Annett’s Electric Elevators (1927): Part 1

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.