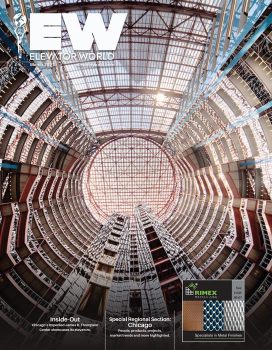

Chicago’s imperiled James R. Thompson Center proudly showcases its mechanical equipment, including elevators.

photos © JAHN

As the pandemic wove a deadly path around the world, it ironically provided a stay of execution for the James R. Thompson Center in Chicago’s downtown Loop: in May 2020, the State of Illinois pushed the timeline to find a buyer for the controversial property from the end of 2020 to April 2022. It could be postponed even further.[1] Once the property is sold, preservationists fear it could be headed for the wrecking ball.

That possibility became almost certain when, in February, the state of Illinois purchased a new office building and planned to move approximately 900 employees out of the Thompson Center.

Originally the State of Illinois Center, the Thompson Center has inspired and outraged citizens and critics since it opened in 1985. Designed by German-born Chicago architect Helmut Jahn, the structure marks a schism in the design and typology of government architecture. It is one of America’s most debated public buildings. Housing the state’s government offices, a Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) train station and numerous retailers such as fast-food restaurants, the 1.2- million-ft2 structure occupies a full city block across from City Hall. Quoting an article that originally appeared in STIRworld.com, ArchDaily recently observed:

“Walking around it on three sides will not reveal anything remarkable, but come to the intersection of West Randolph and North Clark streets — the southeast corner — and you will be knocked off your feet by the sweeping, three tiers of conically curved and angled setbacks. This surprising move generously frees up pricey urban land for a triangular public plaza. There are trees; benches; the childlike, colossal sculpture ‘Monument With Standing Beast’ (fiberglass, 1984) by Jean Dubuffet; and multiple options for shortcuts and rare vantage points in the heart of the dense metropolis. The glass-and-steel building may have been nicknamed ‘starship’ for its futuristic shape that seems to have landed from space in the shadows of the Miesian boxes around it, but, according to its creator [Jahn], it is a symbolic structure, a contemporary take on the traditional state capitol — a domed government building.

“Topped with a sliced-off cylindrical crown, the center projects its iconic silhouette on the city’s skyline and serves as a central skylight over the immense, 17-story, 160-ft-diameter rotunda below. Entering this high-tech, cathedral-like kaleidoscopic space is nothing short of breathtaking. It is invigorated by moving escalators and glass-enclosed elevators, constantly shifting sunlight and shadows, and streams of people who come here for all sorts of reasons. . . .”[2]

Panoramic glass cabs glide effortlessly through the atrium, affording a rhythm and kinetic vibrancy to the space as riders go to and fro.

The building combines postmodern aesthetics with structural engineering, resulting in one of the best examples of high-tech architecture and inside-out buildings in the U.S. It is served by 14 Montgomery Elevator elevators installed by Chicago’s Mid-American Elevator installed when the building opened in 1985. The center-opening elevators each have a capacity of 2500 lb and travel at 500 ft/min.

State Gov. James R. Thompson, for whom the building was named, remained a proponent of the design — even after years of criticism — until his death in August 2020. After rejecting a series of more typical proposals, Thompson sought an architect who would create a monument for the city better aligned with the era. Jahn’s selected design is an awe-inspiring configuration with offices coalesced around a grand scheme of openness. Formulating an alternative model for government offices, the governor felt value signaling was important in a new state building. In his endeavor to modernize the typology, a scheme of openness (a metaphor for a transparent government) was adopted and used throughout the project with drastic consequences.

The structure has curved, single-paned, non-insulated glass panels (rather than double-paned panels, which, in the beginning, were deemed cost prohibitive). This resulted in overheating in the summer and cold drafts in the winter.[2] Maintaining a comfortable temperature in the structure remains “very costly.” Further, the structure is estimated to need approximately US$325 million in repairs.[1]

Still, the building is beloved by many. The theme of transparency can be felt throughout the building and is highlighted in many of the architectural elements, from its clear glass façade to the open-plan offices. Among the transparent architectural features is a network of high-speed elevators and mechanical equipment that lend a machine-like character to the building. Exposed metallic columns, cables and counterweights obliterate the typical shafts and corridors that conceal the machinery hidden in most buildings. Notably, the machine room, a space often enclosed between the top floor and roof, is on full display, encased in tinted glass as part of the atrium décor.

Panoramic glass cabs glide effortlessly through the atrium, affording a rhythm and kinetic vibrancy to the space as riders go to and fro. Commuters, tourists, shoppers and citizens throng the center, making their way around the building by way of the interlacing VT system not celebrated in other styles of architecture. Escalators and metal staircases weave floors together, while the towering elevator shafts anchor the ceiling to the underground gallery below.

Throughout the building, the original Montgomery equipment — 14 elevators and four escalators[3] — shuttle workers past colorful interiors splashed in blue and salmon red (a toned-down take on “red, white and blue” and a nod to the color scheme of high-tech architecture that proliferated almost a decade earlier with buildings like the Centre Pompidou library/museum in Paris and B&B Italia furniture factory in Milan, Italy).

However, the decision to expose everything posed a number of problems. As far as the workers were concerned, the elevators were noisy and annoying. Changes were required, and, after being deemed aesthetically acceptable by Jahn, an acoustical shield was designed to suppress the noise. This also somewhat masked the mechanical components.

Exposed machinery elevates the sensory experience of the building that houses it. Not only is it an interesting sight to watch the elevators at the Thompson Center with their vaulted tops move up and down, but to travel openly through a building without the blind spots created by conventional architecture wins over architectural enthusiasts and conservationists alike.

Look down the elevator bays projecting into the atrium and enjoy a spectacular view of the inlaid marble rosette on the concourse level or people moving below.

Look down the elevator bays projecting into the atrium, and enjoy spectacular views of the inlaid marble rosette on the concourse level or people moving below. The combination of glass-paneled walls and ceiling and marble-inlaid floors infuse stylishness into the vast expanse of postmodernism. Despite initial construction flaws and hefty maintenance costs, the singular architectural vision of an open, accessible and inspiring civic building remains intact. Regardless, the building faces an uncertain future. Local conservation groups have fought for years to save the building as state representatives continue to explore selling it.

Recently, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the Thompson Center one the nation’s 11 most endangered sites. In announcing its list, the National Trust called the building “Chicago’s foremost example of grandly scaled Post-Modernism” and the youngest building to ever appear on the list. Symbolic or schismatic, the unconventional building rises out of Chicago’s Downtown Loop proudly displaying, rather than hiding, its structure and mechanical equipment.

For now, the Thompson Center remains a worldwide attraction, and its glass elevators animate the exciting space and offer a chance to observe the inimitable geometry and feel of the space. A few years ago, Jahn pitched a plan to save his creation by incorporating other uses and adding a supertall,[4] but realizing that seems doubtful. Although its central location is desirable, drawbacks and obstacles remain: in addition to the hundreds of millions in repairs, whoever buys the building would need to negotiate with the city and CTA about operating the station that occupies a portion of it. Then, there is a master lease for the retail tenants occupying the lower floors that doesn’t expire until 2034.[1]

References

[1] Petrella, Dan and Ori, Ryan. “Pandemic Provides Latest Snag in State’s Long-Simmering Efforts to Sell Thompson Center,” Chicago Tribune, November 28, 2020.

[2] “The Thompson Center: A Building Facing Demolition Threat in Chicago,” ArchDaily, December 29, 2020.

[3] emporis.com/buildings/117313/thompson-center-chicago-il-usa

[4] Hickman, Matt. “Helmut Jahn Pitches Proposal to Save Chicago’s Thompson Center,” The Architect’s Newspaper, February 26, 2020.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.