Elevator Car Fans 1880 – 1930

Jul 1, 2025

Historical approach reveals many insights.

by Dr. Lee Gray, EW Correspondent

The history of the elevator car also embraces the history of a range of accessories that enhanced the users’ experience. These accessories included seats, lights, floor position indicators, floor push buttons and fans. The history of elevator car fan systems from 1880 to 1930 reveals a gradual sophistication in fan design, a consistent “directional” approach regarding fan operation (which way the wind blew) and an important operational shift at its conclusion.

One of the first references to an elevator car fan appeared in an 1880 patent: Fan Attachment for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 227,497 (May 11, 1880). The inventor, Luke Davis of Boston, described his design as follows:

“The object of this invention is to provide a simple device for ventilating passenger-elevator cars … The invention consists of a fan fixed in an elevator-car, and having on one end a sheave, around which a turn is made of a rope that is stretched taut from the top to the bottom of the elevator shaft or well so that as the car moves up or down the fan is revolved and creates a current of air to ventilate the car shaft … It is obvious that the fans or blades will create a constant disturbance of air in the shafts, and consequently constant currents and circulation of air as the elevator or car moves up or down.” [1]

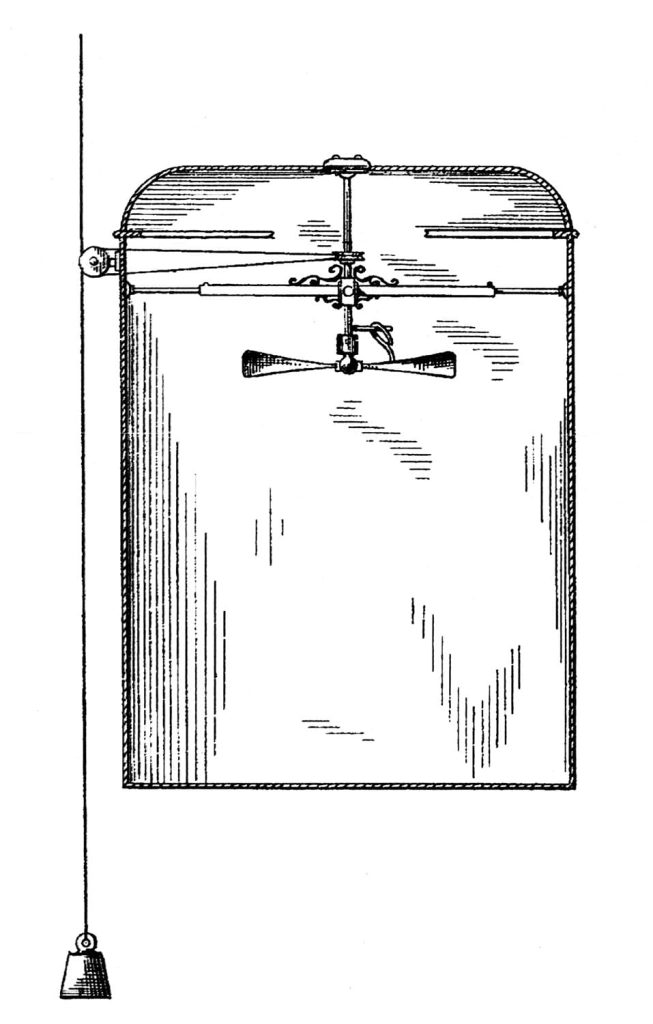

The patent drawings depict a linear fan, which was activated by the motion of the car (Figure 1). The somewhat confusing patent text, with its reference to the fan creating “a current of air to ventilate the car shaft,” coupled with the rudimentary drawings, appear to indicate a simplistic design idea rather than a serious proposal. This impression of Davis’s scheme is countered by an advertisement that appeared in the August 27, 1881, issue of Scientific American: “Ventilating fan for passenger elevators. Patent for sale. Has been tested, and is in daily operation. Satisfactory testimonials of efficiency. Apply to Luke Davis, care of Hovey & Co., Boston, Mass.”[2] Davis also exhibited his fan at the Fourteenth Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, held in Boston in the fall of 1881. An exhibition jury, “for novelty of application, great simplicity, and performing its work with little power,” awarded Davis a Bronze Medal.[3]

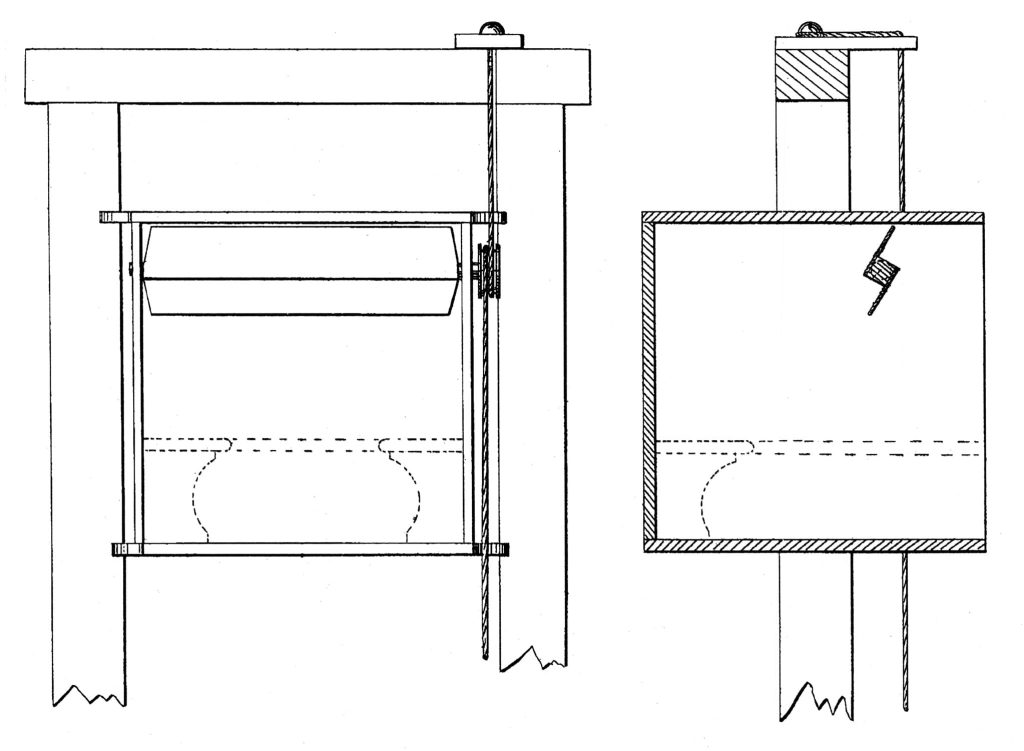

While the actual commercial success of Davis’s design is impossible to gauge, there is no doubt it captured the attention of his contemporaries and, in fact, appears to have directly influenced the next elevator fan patent. In 1885, Richard Marshall of Brooklyn patented a fan that resembled Davis’s in its design and operation (Figure 2):

“The object of this invention is to provide a practical fan attachment for elevators; and the invention consists, principally, of suitable gearing arranged to be revolved by the up and down movement of the elevator cage, combined with suitable means for transmitting the motion of the gearing to the fan arranged at the top of the cage.”[4]

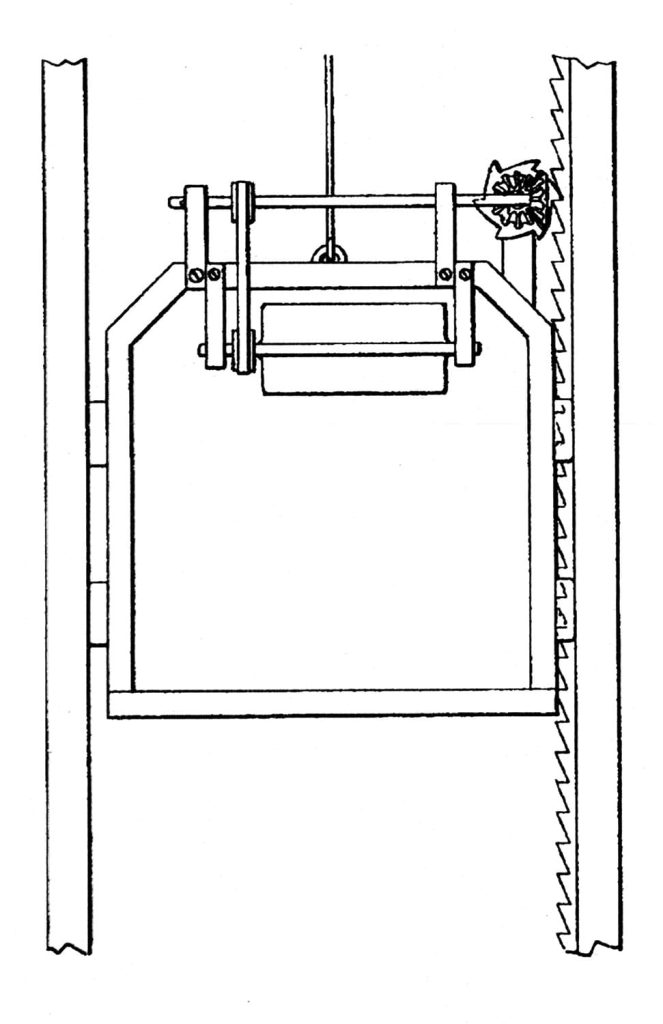

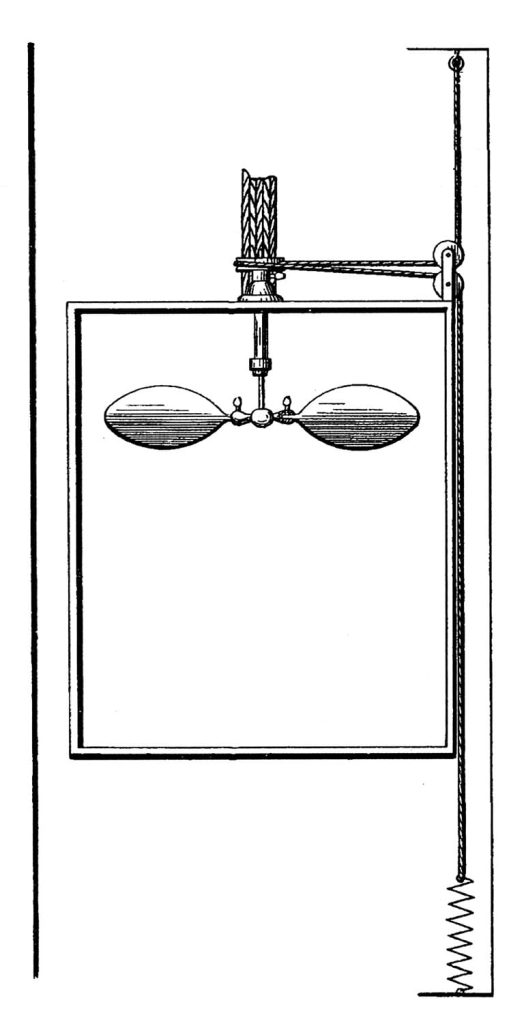

One of the first designs to incorporate a more “normative” fan-blade scheme was patented by Francis Sasse of Washington, D.C. (Figure 3). This design employed “a rotary fan … automatically operated by the movement of the car … through the medium of a cord suspended in said elevator-shaft engaging a pulley on the fan-shaft.”[5] Sasse was also the first to clearly articulate the need for a fan in a passenger elevator car: “In many elevator-cars the air is very close and uncomfortably warm, owing to the lack of ventilation therein. Especially is this the case in warm weather, and in such cars as require a lighted gas-jet, because of the heat and unpleasant odors generated thereby.”[5] In 1890, Arthur Richter and James H. Lancaster of NY patented a similar design (Figure 4).[6]

A fundamental design flaw in the four schemes referenced thus far was their reliance on the car’s movement to power the fan. This would have resulted in the fan starting and stopping as the car traveled through the shaft and, perhaps most concerning, the possibility of the fan achieving a terrifying velocity in a high-speed elevator. The development of the electric fan in the 1880s presented a solution to the problem of providing a consistent and sustained flow of air within an elevator car. The first use of an electric fan in an elevator car is unknown. In 1911, the Emerson Electric Manufacturing Co. of NY characterized the state of the art as follows:

“In many office buildings, hotels and apartment buildings it is customary to place a small fan in one corner of the elevator near the top of the car for the comfort of the operator when the car is stationary, as well as for the convenience of the patrons of the building. Heretofore the majority of fans used for this purpose have been the 12-in. trunnion bracket fans or the 8-in. hinged type motors used as bracket fans. To attach motors with the ordinary bracket base it has often been necessary to mount a wood block in the framework of the car, or to drill and tap holes in the iron framework at considerable inconvenience and expense.”[7]

This summary of the standard approach and its attendant problems appeared in an article titled, “A Fan for the Elevator,” which was published in the company’s monthly magazine. The article also included, not surprisingly, a solution to a problem that was predicated on the use of an Emerson fan:

“The Emerson bedroom type fan with the bracket support, which was designed for the corner post of a metal bed is easily the most convenient as well as satisfactory type of fan to install in the elevator. The bracket support intended for the post of the bed fits the corner post of the elevator car equally well without the necessity for special machine work or carpentry. The full swivel-trunnion of the Emerson bedroom type fan permits adjustment of the motor to throw the breeze to any position desired. The eight-ft cords with plug and pendant switch, which are regularly furnished with the bedroom type, may be cut off to suitable lengths for connection to the line, and to allow the switch to hang from the motor at a convenient height in the car. As soon as the possibilities of the bedroom type fan for elevator service are fully appreciated, a great many of these fans will undoubtedly find a permanent place in elevators of modern buildings.”[7]

While the use of a small electric fan located in the upper corner of a car is not illogical, this approach begs the question: Why didn’t designers simply produce an electric version of the Sasse scheme?

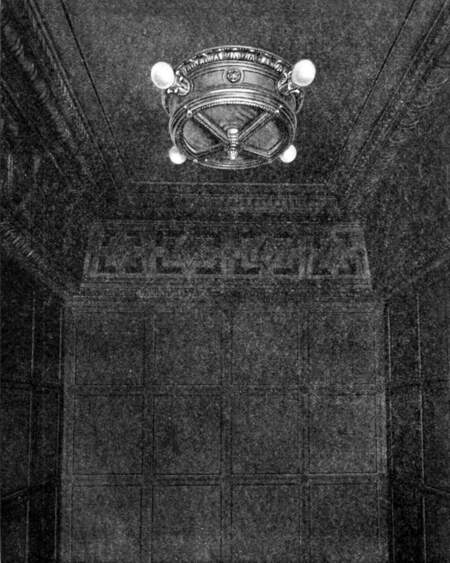

This simple transformation did not, apparently, occur until the 1920s when the Safety Car Heating & Lighting Co. of NY introduced the Fandolier-Chandelier – a combination electric fan and lighting fixture (Figure 5). A 1927 advertisement for this system proclaimed:

“Comfort in Elevators! No More stuffy elevators. No unsightly fans in view, but now hidden within the electric light fixtures. Not one annoying, continuous blast but, correctly diffused air currents of 36 waves per minute, by means of the patented Deflector. ‘Fandolier-Chandeliers’ now make possible elevator comfort, in both winter and summer.”[8]

While this was an elegant solution – the Fandolier-Chandelier was designed by architects Clinton & Russell and the cab design was by the W. S. Tyler Co. Its operation followed the pattern established by Davis in 1880 – the fan blew air into the car.

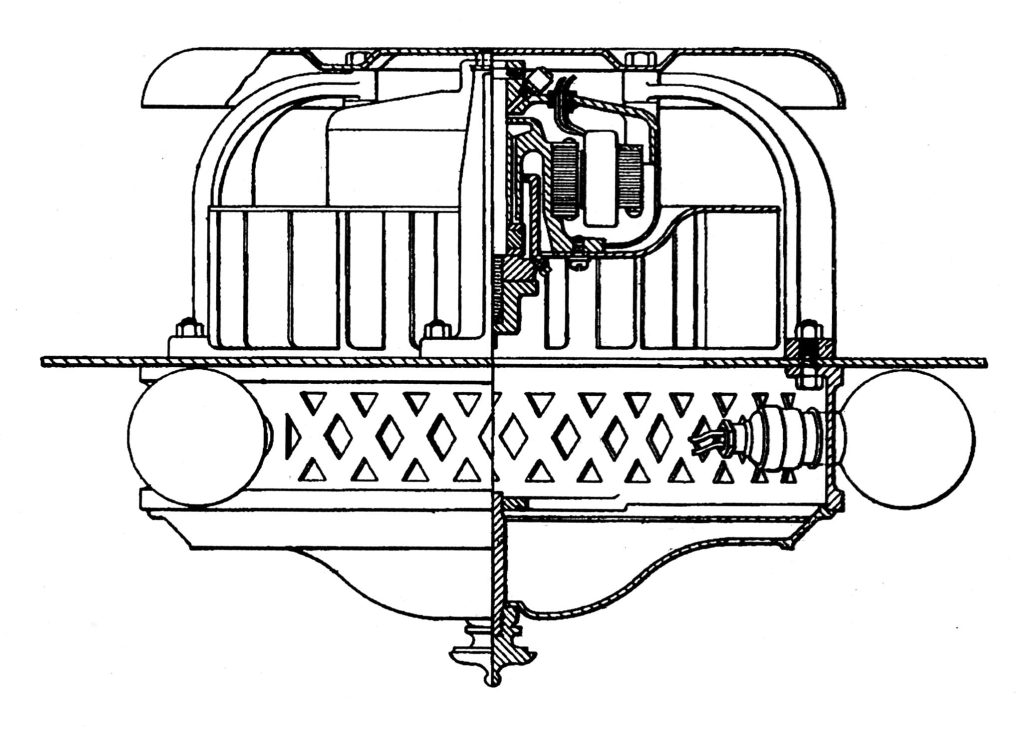

A critical paradigm shift occurred in 1930, with one of its first expressions found in a patent by Otis engineer John C. Knapp. The patent drawings reveal a combination electric fan and lighting fixture design that bears a strong resemblance to the Fandolier-Chandelier (Figure 6). However, in the introduction to his patentb Knapp commented on the need – not for an elevator car fan – but for good ventilation:

“As the elevator art has developed, it has become increasing practice to install closed or substantially closed cabs in certain types of installations. As a result, there is always the possibility of the air in such cabs becoming impure or even stagnant. There is also the possibility of the air becoming impure in other types of cabs, due primarily to heavy traffic conditions. It is desirable, therefore, in installations of the above nature to ventilate the cabs. One feature of the present invention is the provision of a ventilating apparatus adapted to renew the air in an elevator car. Another feature of the invention resides in concealing the ventilating apparatus from occupants of the elevator car. A third feature of the invention resides in the provision of a ventilating device for an elevator car which is of simple and rugged construction, reliable in operation and which may be cheaply manufactured … In carrying out the invention in its preferred embodiment, an opening is provided in the ceiling of the car over which a suction fan is positioned, the fan being driven by a motor mounted on the car. A lighting fixture is arranged within the car to cover the opening, apertures being provided therein to permit the free passage of air to the opening. This fixture is of artistic design so as to present a pleasing appearance to the occupants of the car and is arranged so that the fan and motor are effectually concealed.”[9]

Thus, Knapp’s design marked the end of the era of elevator car fans and introduced the era of elevator car ventilation systems. The latter will be the subject of a future article.

References

1. Luke Davis, Fan Attachment for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 227,497 (May 11, 1880).

2. Advertisement, Scientific American (August 27, 1881).

3. Fourteenth Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, 1881, Boston: Alfred Mudge & Sons, Printers (1881).

4. Richard Marshall, Fan Attachment for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 316,633 (April 28, 1885).

5. Francis Sasse, Fan Attachment for Elevator-Cars, U.S. Patent No. 350,947 (October 19, 1886).

6. Arthur Richter and James H. Lancaster, Fan for Elevator-Cars, U.S. Patent No. 432,768 (July 22, 1890).

7. “A Fan for the Elevator,” The Emersion Monthly (June 1911).

8. Advertisement: The Safety Car Heating & Lighting Co., American Bankers Association Journal (April 1927).

9. John C. Knapp, Ventilating Apparatus, U.S. Patent No. 1,767,988 (June 24, 1930).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.