A Look Back: Elevator World in 1980

Feb 1, 2011

Looking back at history shows there are a few similarities between the industry’s current situation and that of 1980.

The “job” of the historian may be described as follows: he or she looks back at a specific period of time, surveys the facts, then offers an assessment of the period. In other words, historians “tell the story” of that period in a way that allows others to understand both what happened and why it happened. Of course, the trajectory and meaning of the story is directly affected by the collection of facts that the historian examines. It is possible to gather a variety of sets of information from the same period, each of which could lead to different conclusions.

The historian’s task is thus slightly more complex than simply “looking back.” He or she must first determine how to gather information (not everything is important) and how to assess what is found (not every fact is of equal importance). The historian also looks for patterns, or the recurrence of similar events over time, that may enhance the story and thus his or her – and the reader’s – understanding of a given period. These historical patterns are also occasionally used as a means to understand the present and predict future events. With this thought in mind, there are a few similarities between our current situation and the year that is the subject of this month’s article.

Economist Peter S. Nagan’s January 1980 ELEVATOR WORLD column “Date-Line Washington” opened with the statement that the economic forecast for the year was “a short, moderate recession followed by a moderate recovery.” The author noted that the recession was “finally getting underway” and that he anticipated unemployment would reach 6% by year’s end. Nagan’s forecast thus established a pessimistic background against which EW pursued its annual editorial agenda, which addressed the increasing use of computers, international industry trends, the role of women and environmental concerns.

The increasing use of computers was the subject of several articles published over the course of the year. The first of these articles, “A Data Logger for Lift Traffic Engineering,” appeared in the January issue and was written by British engineer E.M. McKay. The data logger employed a PDP 11/05 mini-computer and an RX-01 dual disk drive, both of which were manufactured by Digital Equipment Corp. The dual disk drive accommodated two 8-inch floppy disks, each of which could hold up to 256 kilobytes of data. One disk contained the computer operating system, various utility programs and the data logger program, while the other disk recorded the data. According to McKay:

“Communication with the system is via a teleprinter (Data Dynamics 303) set to run at 300 bauds. It also provides on-site copy, as and when required, of the data being written to the data disk.”

The system was capable of recording data from four cars serving 24 floors, and data strings included the floor number; car number; car direction (up, down or parked); response time for an up call (in seconds); response time for a down call (in seconds); door hold time (in seconds); flight time (in seconds); door opening time (in tenths of seconds); and door closing time (in tenths of seconds). While McKay stated, “Thus far it has been used primarily for the study of traffic performance,” he also noted, “During the course of this work, some use has also been made of its potential for fault diagnosis.” The data logger was developed at the University of Manchester by a team led by G.C. Barney.

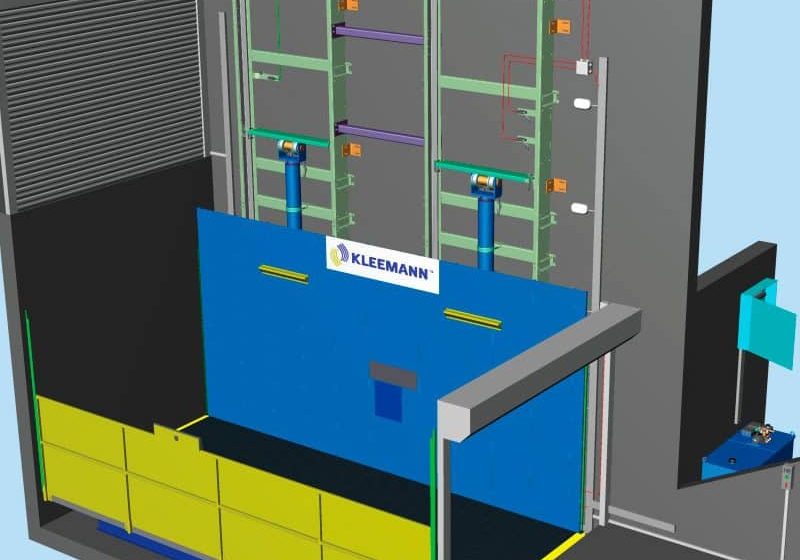

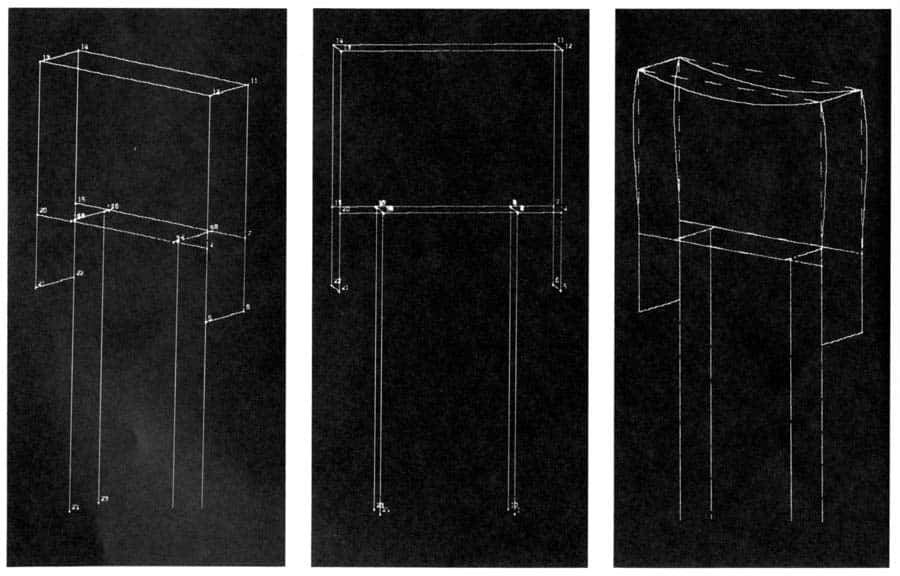

In December, EW reported on Otis’ use of computer-based structural analysis in the design of a large stage elevator for the MGM Grand Hotel in Reno, Nevada. Otis engineers employed a structural design program called FRAME, which had been developed by Structural Dynamics Research Corp. (SDRC) of Cincinnati. Access to the program was via an in-house terminal that accessed the software through a third party’s computer network – in this case, Comshare, described as “an international computer services firm” located in Ann Arbor, Michigan. FRAME allowed the engineers to design and test various prototypes, which resulted in a 50% reduction in design time, in comparison to the process involved with a similar elevator designed in 1975 for the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas.

Reflecting the enthusiasm and optimism associated with the introduction of computer-based design strategies, EW reported that the design process, during which “the engineer can construct his prototype and stress test it under various loading conditions” was “like watching television.” However, the stark black images that illustrated the article, which were printed from the computer screen depicting the simple wire-frame diagrams produced by the software, served as a reminder that the “television program” (most likely “broadcast” in the eerie green or orange glow of early monitors) required greater stamina than was required of the average television viewer.

Otis’ use of computer-based design strategies, while noteworthy within the elevator industry, simply followed current research and design trends found in many American industries. However, earlier in the year, Robert L. Cole, president of Otis’ North American operations, had announced a truly innovative use of computers in the world of vertical transportation. In March, EW reported on the development of Otis’ Elevonic 101 Control System, which Cole referred to as “the elevator technology of the 80s.” Described as the “first fully integrated microcomputer control system,” Elevonic 101 controlled “every aspect of elevator operations . . . velocity, position, direction, travel time, waiting time, door operation, car assignment, energy use and system health.”

The system featured three basic components: a group controller (for all cars in a multi-car installation), car controllers (one for each car in a group) and individual cab controllers that were mounted on top of the cars. The design was characterized as a “smart” control system, because information was “continually fed back and forth between the system’s microcomputer,” which allowed “the system to continually react to changing passenger traffic flow.” As part of its publicity campaign, Otis published a booklet explaining the operation of the Elevonic 101 Control System: Everything You Wanted to Know About Microcomputer Elevator Control Systems, But Were Afraid to Ask. It is of interest to note that Otis felt it was necessary for the booklet to include a glossary of common terms “used in the microcomputer field.”

In 1980, EW continued its longstanding practice of reporting on industry events across the globe. This editorial stance was reflected in the magazine’s cover designs – various months featured illustrations of elevator installations in England, Australia and Sweden, and February’s cover was a compilation of pictures of funiculars from Germany, Switzerland, Italy, France and the former Yugoslavia. The latter cover announced a lengthy feature article by EW founder William C. Sturgeon, “In Search of the Inclines,” which outlined the history of the funicular and examined its continued use in Europe. Equally comprehensive but very different in scope and focus was the October Annual Study issue titled “On the Rim of the Caribbean: Monitoring the Elevator Industry in Middle America.” This issue offered readers detailed studies of the elevator industries of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Guatemala, and Mexico. EW’s coverage was not limited to the Americas and Europe: the March issue included two feature articles on the elevator industry in Japan. These articles and countless other news briefs and shorter articles effectively revealed the emerging global marketplace and changing global economy that challenged all industry members.

However, not all industry challenges were determined by market forces; some were the result of shifts in American culture and changing attitudes toward the workplace and workforce. This was the subject of an editorial written in April by current EW President and Publisher Ricia S. Hendrick. In April 1980, Hendrick was managing editor of EW, and the impetus for her editorial derived from a panel discussion she had orchestrated at the 1979 National Association of Elevator Contractors (NAEC) convention. The panel, designed in collaboration with Helen K. Barbee, president of Barbee-Curran Elevator Co. of Washington, D.C., became the Fourth NAEC Women’s Seminar. The topic was defined as “The Role of Women in the Elevator Industry – Past, Present and Future.” In addition to Hendrick, the panel included Marie Lustig McDonald, president of McDonald Elevator Co. in San Francisco; Bob Jacobs, president of Gust Lagerquist & Sons of Minneapolis; and Sonya Ojeda, secretary to the National Elevator Industry, Inc. Executive Director Frank Aquilino.

Approximately 150 women attended the panel, which featured an opening keynote address by Hendrick consisting of a thorough overview of women in the industrial workplace from World War II to the present. In the context of this broad overview, she outlined the three primary paths women had taken to enter the elevator industry:

“(1) Women in Traditional Roles after World War II who moved into managerial roles because of family relationships, (2) Women outside of family relationships who moved into Non-Traditional Roles that were managerial, sales or technically oriented, and, most recently, (3) Women moving into field positions in maintenance, repairs and construction.”

During the course of her remarks Hendrick also identified other women (in addition to herself, Barbee, MacDonald and Ojeda) who held industry leadership positions: Pauline Park, president of Oliver & Williams Elevator Co. of Los Angeles; Anna Shrout, president of Wright & Mack Co. of Omaha, Nebraska; and Betty Wilson, president of American Elevator and Machine Co. of Louisville, Kentucky.

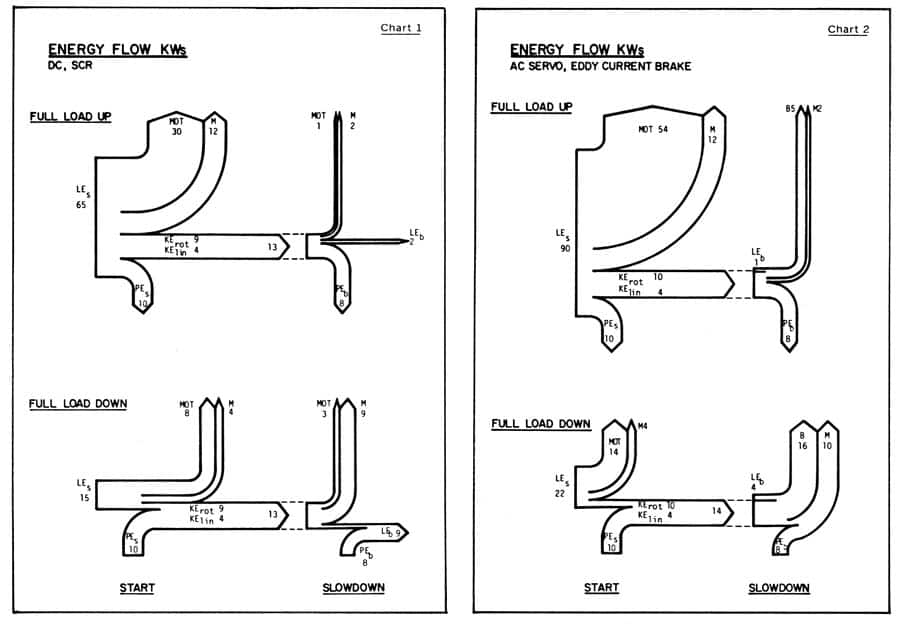

Paralleling the rise of computers, global marketplace and changing workforce was the rise of the environmental movement. In the November issue article titled “The Energy Consumption of Elevators: A Comparative Analysis,” Joris Schroeder observed,

“Though the elevator industry has introduced new energy-saving drive systems, little has been published on methods for comparing the energy-efficiency of elevator drives, or total elevator systems.”

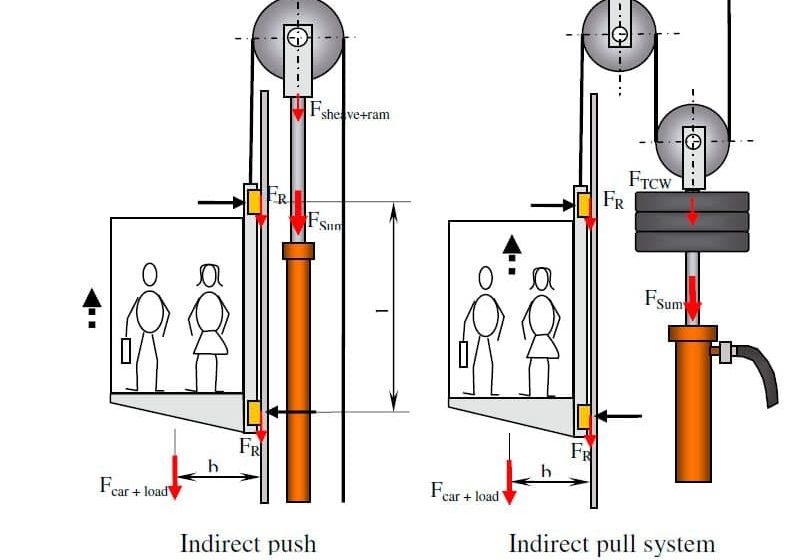

According to Schroeder, “one of the main obstacles” to developing a comparative analytical methodology was “that the energy consumption of an elevator is subject to so many parameters that it is difficult to separate the ones that can be ignored when comparing different drive systems.” However, in his article, he outlined what he believed to be “a method of analyzing the energy flow in elevator systems that is reasonably simple. . . adequately precise” and which permitted “fair judgments on the quality of drive systems from the standpoint of energy efficiency.” While the “science” of Schroeder’s article is of interest, perhaps the most striking aspect of his proposed method was the energy-flow diagrams the he developed. These were, in fact, of such visual quality that they were abstracted for the November cover image.

1980 closed with another economic forecast by Peter Nagan that appeared, on the surface, to balance the one that had opened the year. According to Nagan, “A gradual recovery in business activity is now underway. Economists in government and industry are fairly certain about that, although they admit that the trend is not as clear as they’d like.” Of course, our historical perspective allows us to recognize that Nagan’s cautious optimism was more than slightly misplaced – not only did the recession continue,it gained strength over the next two years until it peaked in early 1983 when the nation’s unemployment rate reached 10.4 %.

As noted in my introduction, this would appear to reinforce the presence of a historical pattern that could be used as a means to understand our present situation. The essence of this approach was first stated by author/ philosopher George Santayana (1863-1952) in 1905 when he stated, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” A simplistic reading of this statement assumes that historical patterns repeat themselves in precisely the same manner, over and over again. Thus, the same solutions may also be used repeatedly. However, although the vertical-transportation industry appears to face similar challenges today to those of 30 years ago – increasing use of computers, a global marketplace and economy, a changing workforce and environmental concerns – when the present is accurately compared to the past, the context in which we now operate is so profoundly different that new solutions must be sought for what are, in many ways, new problems.

Although my “job” as a historian is to keep my eyes firmly looking back in an attempt to understand the past, I am intrigued by the appearance of these historical patterns and recurring events that, more often than not, serve to highlight the differences between distinct periods and between present and past.

This data logger, developed at the University of Manchester, employed a PDP 11/05 mini-computer and an RX-01 dual disk drive.

Wire-frame diagrams generated by the SDRC FRAME program

EW President and Publisher Ricia S. Hendrick in April 1980

Energy-flow diagrams developed by Joris Schroeder

EW cover, November 1980

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.