U.K. consultant puts the current crisis and its implications for the industry into context.

In the last issue of ELEVATOR WORLD UK, I wrote of the prospects for the industry, together with some of the likely forthcoming changes, challenges and opportunities, and expressed optimism about the future of the industry and its capacity to develop in response to changes in the wider environment. That was less than nine weeks ago from the time of this writing. The global external environment now looks less rosy. However, things come and go. I’ve worked through the Three-Day Week; the Winter of Discontent; the recessions of the early 1980s; the exchange-rate-driven downturn of the late 1980s/early 1990s; the dot-com boom and bust of 1999 and 2000; 9/11; and, more recently, the financial crash of 2007-2009, the effects of which remain unresolved. The very fact I am here at all is a substantiation of my grandfather’s patient fortitude in surviving six years of World War I and, in its immediate wake, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which history indicates was very similar in effect and response to our current crisis.

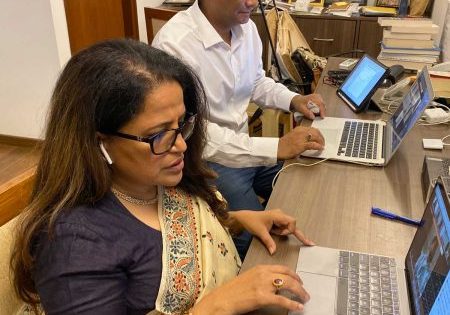

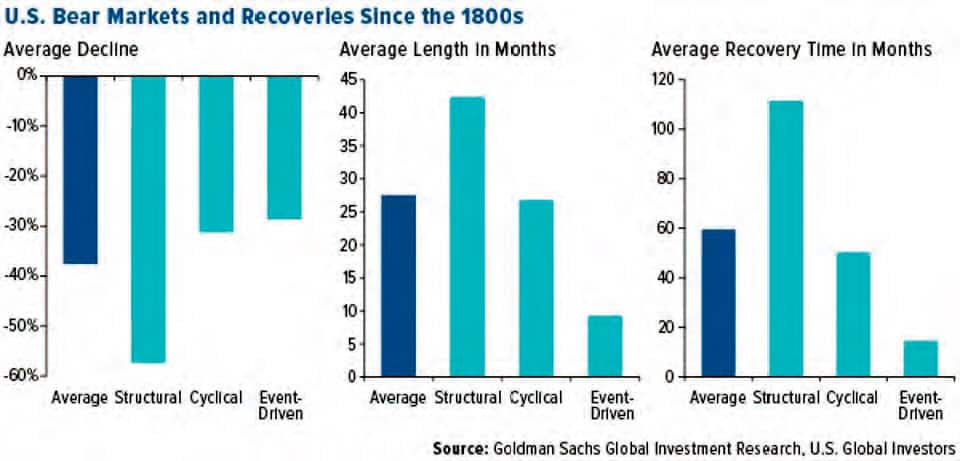

While the current crisis is serious, it has arrived, and it will go, and the world will go on, although perhaps not in its previous socio-political-economic guise. But, go on it will. Indeed, the indication from Figures 1 and 2, which highlight the different forms of recession and associated durations, is that the economic fallout from this event may prove not as destructive or enduring as that of the 1929 and 2007 structural recessions. While the good news is that the economy inevitably bounces back, the difficulty has always been that things change thereafter. I have no doubt this will hold true as we emerge from the current crisis and start to feel our way forward.

As nations strive to respond to the immediacy of the crisis, it seems inevitable that questions will be asked about the role of governments and national leaders in relation to the efficacy of their responses or, in some cases, lack thereof. Questions will also be asked related to the extent to which states were prepared, particularly given this event was not wholly unforeseen, unforeseeable or without precedent.

Overall, the people of the U.K., together with our healthcare institutions, have responded magnificently, with everyone rallying around the need to do what is necessary in response to the crisis. Regardless of all the problems and risks, shortages of equipment and lack of preparedness, our National Health Service (NHS) staff has performed miracles. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of our government. For at least 10 years now, NHS has been beset by political interference, underfunding and fallout from government-supported — but mismanaged — capital-investment projects, including the failure of Carillion (the largest construction bankruptcy in U.K. history[1])and the effect this had on a number of major hospital development projects.

Despite the promises made back in 2010, austerity policies promoted by the last four governments have failed. Indeed, it is only in the face of the likely consequence of this failure that the current government began to espouse policies based on investment in our industries and public services, and in regions of the country that were left behind. This has been lacking for too long.

Regardless of sociopolitical ideologies, it is the state (in all affected nations) that is required to step to the fore in times of crisis. The “free market = good” and “state/public-sector = bad” mantra, which has been overplayed for too many years now, seems nonsensical in times of crisis. It is the state, in our case principally the NHS, that is called upon to deal with the crisis, while our ministers of state appear inept and incompetent in organizing supplies, communicating and managing the situation. The old saying, “In times of crisis, the state really is the bank of last resort,” is true. In the daily TV briefings, it is the explanations, advice and support provided by NHS managers and scientists that have been exemplary to the extent that it is little short of embarrassing to observe these good people standing alongside our political leaders, who we see looking helpless and inept.

If government has not performed well, then it is heartening to note that the great majority of private-sector employers (with only a few, perhaps predictable, exceptions) have opted to forego dividend payouts and support their employees and workforces as best they can and with welcome support from the Treasury.

Responsible government and leadership require that those in power act in the best interests of their people, regardless of ideological considerations, to ensure the state maintains the level of preparedness necessary to deal with foreseeable, but rare and/or unpredictable events. For some years, this duty has been ignored — and perhaps even considered old-fashioned or redundant — in light of technology and free-market ideologies. The reality is that these allegedly old-fashioned concepts of risk management reflect a proper approach to government, the application of which is essential in technologically developed societies. It seems that nature has readily exposed the limits of technology, together with our lack of preparedness.

As the world emerges from the crisis, the different responses and approaches adopted by different countries (which, as I write, appear to be producing different outcomes) will no doubt become the yardstick by which leadership is measured. Let us hope the U.K. is not seen lacking in this respect.

So what, then, are the prospects for the future? The world economy, including that of the U.K., will inevitably fall into recession. I say this because the shutdown of trade for such an extended period is certain to generate the technical elements of a recession. However, economic history indicates that the effects of event-driven recessions, as opposed to those arising from structural or cyclical factors, tend to be less destructive in overall effect and longevity, and have quicker recoveries (Figures 1 and 2).

Let us hope this is the case here, albeit that, during the transition period, extensive state support of industry and commerce will be required. Supply chains for supermarkets have held up well and should pull through relatively well. While law firms continue to operate, albeit in a restricted form, the insolvency and force majeure and delay claims, together with insurance-related business disruption claims, should keep them occupied for years to come.

Inevitably, our industry firms are adversely affected by the financial effects and disruptive nature of the crisis. While government has promised extensive aid and support, it absolutely must deliver this to support our public services, firms and infrastructure in whatever ways required, to kickstart the economy and return us to our social norms as soon as it is safe to do so.

During the 2007 recession, the construction sector lost many people, many of whom left the workforce never to return, depleting what was already a seriously weak workforce. We have, hopefully, learned from this, and firms have retained their workforces. However, many of the foreign workers who were in the U.K. prior to the crisis have, understandably, returned home. Throughout the country, we have big buildings awaiting completion, with more on the planning boards. The country is in dire need of infrastructure upgrades, which government must ensure receives the necessary financial and planning support.

A new construction-sector workforce and operating structure, which will be required to support the firms that survive the current crisis (regardless of negative press reporting, the U.K. retains a number of very strong construction firms), will become critical in terms of moving forward and recovering from recession.

The thorny question of Brexit must also be considered. While it was always recognized that the U.K. was not financially well-positioned to undertake Brexit, one must wonder whether and how such a significant step can now be taken. Also, in light of the crisis and the enforced realization that we are not an island immune from world events, one must wonder whether the whole Brexit proposition is desirable and/or achievable. The single priority of government must be the immediate and rapid restart of the economy. For example, an immediate concern affecting all European countries relates to the availability of labor for coming food harvests.

While the good news is that the economy inevitably bounces back, the difficulty has always been that things change thereafter. I have no doubt this will hold true as we emerge from the current crisis and start to feel our way forward.

Our industry may be considered a microcosm of the wider economy, and firms will need support to bounce back. I note a level of bitching in relation to alleged improper operating practices by certain industry firms, which appear to primarily affect the statutory inspection sector. While such complaints may or may not attract some element of credence, the general atmosphere of bitching and backbiting during a time of crisis is unseemly.

When the world economy restarts, we have regulatory changes, technological developments and operational management changes still to come. These have not gone away. The Grenfell Inquiry, together with the outcome (if there is one) of the government review of construction-industry payment practices, will be concluded. This will bring about structural changes in management, technology, materials application and working practices to prevail upon what is already a somewhat beleaguered industry.

Otis and thyssenkrupp Elevator are now standalone companies. The effect of the restructuring of two massive, internationally operating firms, coupled with the fallout from the crisis, can only have a significant disruptive effect on industry structure. The industry’s customer base will change.

In the retail sector, many firms, attracted by management-school theory, sold their accumulated property portfolios to lease them back and release capital to, for example, shareholders or used them for investment. The outcome is substantially weakened firms that, in the case of unforeseen events in the external environment, are no longer able to generate revenues sufficient to meet their lease-and-debt costs, together with a profit. This is how some retailers will disappear.

Leveraged financial takeovers of successful businesses provide little benefit for consumers (prices do not fall, and services do not improve and, often, deteriorate) and result only in a weakened business and reduced service/product offering. Venture capital, in its original form, applied to the development of new technologies, industries and innovation, and provided a basis for entrepreneurs to develop businesses. Its extension into the wider business environment has not benefited markets or consumers, and, in times like these, firms are exposed to untenable levels of debt.

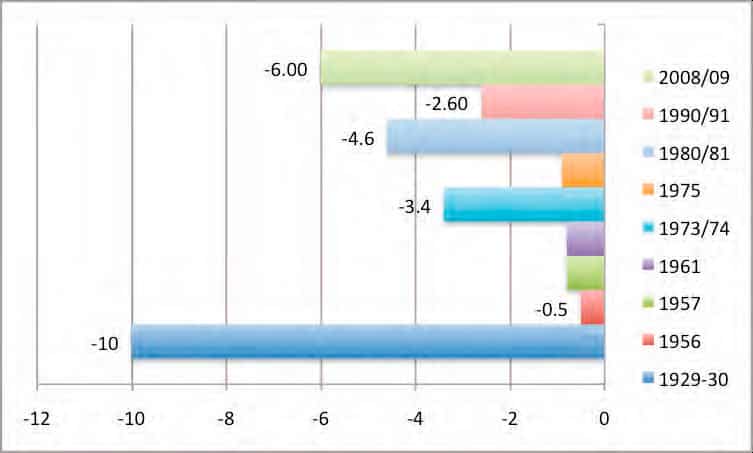

Figure 3 highlights how cycles of technological innovation and development change economies and the basis of competition and, in doing so, disrupt established socioeconomic norms and how such changes tend to coincide with significant socioeconomic upheavals.

What have we learned, or perhaps relearned, from the pandemic? Well, we are social beings, and the lockdown has hopefully laid to rest the idea that technology and the internet can run the world. It is the people who count and who must be considered at the forefront of policymaking. In recent years, our high streets have suffered due to the concept that internet retailing is now the predominant means of transaction. However, markets have, since time immemorial, been places where people meet and socialize alongside the conduct of trade. While our retailers have undoubtedly suffered during the crisis, an opportunity arises to rethink retailing. Given people’s sense of value in their social environment, is likely to be reinvigorated after the lifting of the lockdown. (As I write, I am approaching stir-crazy.)

We must also ensure the economic bounce-back is inclusive and that the socioeconomic inequalities and divides that have beset our nation and its different regions are addressed and corrected. In this crisis, it has so often been the lower-paid workers who have been called upon to the provide the essential care and bear the associated risks (often without the necessary personal protective equipment). This must not go unrecognized or unaddressed.

Overall, and regardless of political ideologies, as we enter the so-called “Sixth Kondratieff” (Kondratieff waves are hypothesized cycle-like phenomena in the modern world economy[2]) and its envisaged technological and healthcare innovations, we are presented with an opportunity to engage in a considered review of our future, together with a new start and socioeconomic rebuilding, which we should not allow to pass us by.

References

[1] Reuters. “Carillion Collapse Exposed Flaws in U.K. Government Policy: Lawmakers” (July 9, 2018).

[2] wikipedia.org/wiki/Kondratiev_wave#cite_note-1

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.