All I Want for Christmas Is a Meccano Moving Stairway

Dec 1, 2017

Finding and assembling a model from 1916 is a mission that evokes a range of emotions.

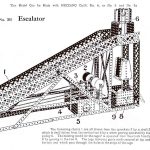

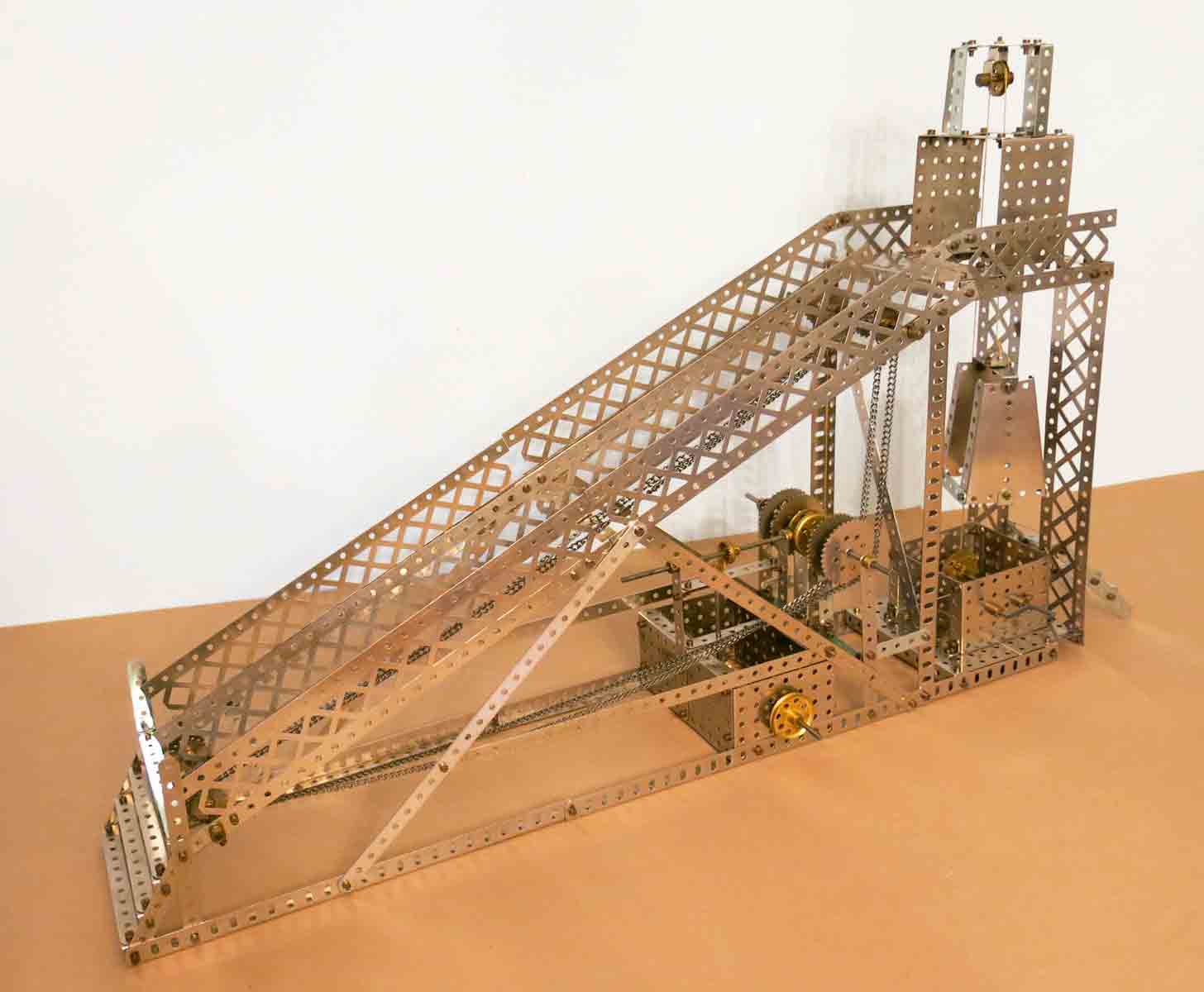

The genesis for this article was the discovery, approximately two years ago, of a 1920 advertisement for Meccano toys. While many European readers will be familiar with the world of Meccano, most American readers are most likely unaware of these remarkable toys. The easiest way to contextualize and define them is that, prior to Erector Sets, there was Meccano, a construction-based toy system created in the early 20th century by English inventor Frank Hornby. The advertisement featured a wonderful illustration of a “Moving Stairway” built of Meccano parts (Figure 1). Further research traced the design to a brochure published in 1916: “Meccano Prize Models: A selection of the models which were awarded prizes in the Meccano Competition 1915-16.” Beginning in 1913, the company sponsored an annual contest that allowed “bright boys” to send in original Meccano designs and compete for cash prizes. The moving stairway was also featured in the 1916 Meccano Manual of Instructions published in England and the U.S. (Figure 2). Unfortunately, neither source included the identity of the designer.

The model is remarkable in several ways. In 1916, although escalators had received considerable publicity due, in large part, to their extensive exhibition at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, they were relatively rare and only found in a few large cities. Thus, the appearance of a toy moving stairway, which was, perhaps, the first popular-culture image of this new technology, prompts questions about its origin. The parallel moving stairs were designed to move in opposite directions when the driving pulley was turned, a feature that reflected the design’s technical sophistication. Although it was not referenced in the drawing or description, it appears that the operation of the moving stairway was predicated on the use of the Meccano clockwork motor, given the presence of a sheave or pulley on the driveshaft (compare this feature to the hand crank used to power the elevator). The model also included an elevator and the realization that the car required guides (albeit they were string) also indicated a high level of technical understanding. These design features raise several questions about the identity of the designer. It seems unlikely that he was a “bright boy.” He was, more likely, a “bright man.” In fact, the introduction to the 1916 Meccano Manual of Instructions speaks to the toy’s imagined use:

“Meccano is sold as a children’s toy, to give them fun, interest them and instruct them in the fascinating world of engineering, but every day sees a fresh use for it. Engineers and architects use it for designing models and inventing movements. Professors and teachers in technical schools use it to demonstrate mechanical principles to their students.”

The precision with which the various parts were made and their inherent constructive logic allowed a more expansive use.

Following the process of tracing the origin of the moving stairway design to 1916 and analyzing the perspective drawing, this investigation took a different path from previous research. The image was sufficiently intriguing and prompted enough questions about the operation of the moving stairways and elevator that the decision was made to attempt to build the model. The drawing in the Meccano Manual of Instructions was accompanied by a parts list and a brief description of the system’s primary parts and basic operation:

“The traversing chains (1) are all driven from the sprockets (2) by a shaft (3), which is itself driven from the vertical rod (4) by a worm gearing operated by the pulley (5). The hoisting cord (6) for the cage (7) is operated from the crank handle (8) by gearing on the box (9). The cage traverses guide cords secured at the top and bottom and which pass through the holes in the strips of the cage.”

This information, when added to the detailed perspective drawing, appeared to provide everything needed to build the combined moving stairway and elevator.

The presence of a two-page illustrated parts catalog (found in the 1916 manual) made it relatively easy to determine what was needed. The first step was the acquisition of vintage Meccano parts. This pursuit involved extensive (and multiple) searches on eBay to find – and purchase – full and partial Meccano sets from 1915-1925. However, this “simple” process was filled with surprises and a steep learning curve. Meccano continued to produce metal model building components that matched its original designs well into the 20th century, and new parts were often found mixed with older, vintage parts. Thus, there are many sets or pieces that look like authentic vintage Meccano components but aren’t, and there are Meccano pieces that are authentic but not “vintage.” One such discovery of Meccano-like sets sold as “The American Model Builder.” In 1911, Francis Wagner founded American Mechanical Toy Co., which produced toys that were essentially exact duplicates of Hornby’s Meccano sets. The matter was resolved in 1921 when Wagner was found guilty of numerous copyright violations and was forced to cease manufacturing his toys.

Once enough components had been collected, the next step was to clean them. Vintage toys are sold under a variety of headings, including the descriptive phrase “barn find,” which typically meant the pieces were rusty, very dirty and (in some cases) in need of repair. Following the cleaning process, the pieces were laid out to give an illustration of the complexity of the challenge that lay ahead (Figure 3). This prompted thoughts of purchasing a moving stairway at Ikea and the realization that the clear Scandinavian directions that always accompany their products were, in fact, nowhere to be found. This was of particular concern regarding features of the model that were hidden due to the nature of the perspective drawing. So, with some mild trepidation on the part of the builder, the next step was to begin assembling the model.

Approximately three weeks’ construction time was allotted (working a few hours every other evening and on the weekends), which assumed that the model (and accompanying History article) could easily be completed to meet the editorial deadline. As the model building commenced, it quickly became evident that the assembly logic of Meccano components did not always follow the system implied in the drawing. Equally apparent was the fact that adult hands are much larger than a child’s, and the small nuts and bolts presented a challenge. The effort also quickly became a trial-and-error process that involved building a portion and then realizing that the sequence in which sections were built was important; thus, sections were built, disassembled, a different portion was built, and the original section reassembled. It was at this point (and there were many others) that the model builder used a few “choice” words that a child would have been strongly discouraged (or more likely forbidden) from using.

Toward the end of the process, with the article deadline fast approaching and with increasing frustration on how to build elements hidden from view in the drawing, the decision was made to “cheat” and use a few additional Meccano components (added to those on the original parts list) to finish the model. A design change was also made to the upper elevator cage landing. As represented in the drawing, the orientation of the openings in the cage permitted access to the elevator by a set of stairs at the rear of the model. However, when the cage reached the upper landing, the “penthouse” design meant that the cage “doors” opened onto blank walls. At this point, the model builder was fully aware that he was very likely overthinking this exercise – after all, it’s just a toy model – and, yet, it seemed like a problem that had to be addressed. The solution once again involved expanding the number of parts to design an appropriate solution.

The completed moving stairway was approximately 24 in. long and 12 in. high and represented a reasonably faithful reconstruction of the original 1916 model (Figure 4). The ingenuity of the model’s designer was evident in the gears used to drive the moving stairways, which included a worm gear, three pinion gears and three contrate gears (Figure 5). (A contrate gear has teeth that project at a right angle to the face of the gear wheel and are used to transfer motion 90°; in 1920, Meccano introduced bevel gears, which offered a better mechanical solution.) The chains traveled on sprocket wheels with four 2-in. sprockets attached to the driveshaft connected to the gearing assembly. Unfortunately, only enough vintage chain to equip one moving stairway was found, and tensioning the chains was more challenging than anticipated (thus the slight sag to one of the driving chains) (Figure 6). The elevator rope design, at least as expressed in the drawing, also proved to be problematic. However, in the interest of time and the need to complete this article, the decision was made (after the use of a few more choice words) to leave its resolution to another day.

According to the 1916 Manual of Instructions, “There is no hard work attached to building Meccano models. All the work and thought have been put into the parts when they were designed, and all you have to do is follow the instructions, and screw the parts together.” This is a lie. It did require thought on the part of the builder, constructing the model was hard work, and there was very little provided that met the definition of meaningful “instructions.” Nonetheless, this effort had many benefits, not the least of which was the ability to assemble a collection of vintage toys and explore the creative expertise of a past designer. There is also the strong possibility that the exploration and refinement of the moving-stairway model will continue (after a suitable period of rest and recovery). Finally, this exercise allowed your humble author and elevator historian to say, in response to repeated questions from his wife, “I am not playing with toys. This is serious research.”

- Figure 1: Meccano advertisement, Popular Mechanics, early 1920s

- Figure 2: “Moving Stairway,” Meccano Manual of Instructions Book No. 1 (1916).

- Figure 3: Moving Stairway parts.

- Figure 4: Meccano Moving Stairway model (model built by your author)

- Figure 5: Meccano Moving Stairway model, detail of moving-stairway gears (model built by your author)

- Figure 6: Meccano Moving Stairway model (model built by your author)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.