The importance of ascending-car overspeed protection and protection against unintended car motion

As we look around the world today, we can marvel at the work ethic and geniuses of mankind. Monuments to those geniuses include the likes of the Empire State Building; World Trade Center, Willis, and Petronas towers; and Burj Khalifa. But just think, none of this would be possible without the elevator – in fact, without the safe elevator.

Elisha Graves Otis is credited with inventing the safe elevator. In 1853 at the Crystal Palace Exhibition, he demonstrated his down-direction safety by standing on a platform, raising the elevator with a rope, then ordering the rope cut. The crowd roared its approval night after night as Otis removed his hat and exclaimed, “All Safe, Gentlemen. All Safe.” Since that day, elevator codes around the world have been constantly updated in an effort to make elevators safer with improvements that require car-door unlocking zones (ASME A17.1/CSA B44 and EN 81), inspection operation with opened doors (A17.1/B44), redundancy and checking of electrical protective devices (A17.1, B44, EN 81), and, in addition to the down-direction safety, ascending-car overspeed (ACO) protection and protection against unintended car motion (UCM) – leaving the floor with opened doors (A.17/B44 and EN 81).

In the event an elevator stops between floors, the unlocking-zone device prevents passengers from exiting the unit but allows them safe exit near the landing (A17.1/B44 and EN 81). Hoistway-access switch operation allows the slow running of a car down from the top floor or up from the bottom floor with open doors. This allows easy access to the top of the car and overhead, or the bottom of the car and pit (A17.1/B44).

Circuits are also required to allow car-top or in-car inspection operation while bypassing car door and/or hoistway door circuits (A17.1/B44). This requirement is safer than the alternative of physically bypassing (jumping) the car and/or hoistway door circuits to run the car for maintenance purposes. Too many times, forgetting those jumpers has led to disastrous consequences by allowing the elevator to run on automatic operation with opened doors.

Passenger safety in the U.S. and Canada improved by leaps and bounds with the adoption of the A17.1-2000/B44, and in Europe with the adoption of EN 81-1, 2009A3. The most important feature of these codes is the redundancy and checking requirements, coupled with ACO protection and protection against leaving the floor with the doors open (UCM).

In the simplest form of checking, when the car door is open, the car- and hoistway-door contacts must also be opened. If either or both are made, a fault is detected, preventing automatic elevator operation. With redundancy, two separate control inputs can be utilized. Automatic operation will also be prevented if both circuits do not operate simultaneously.

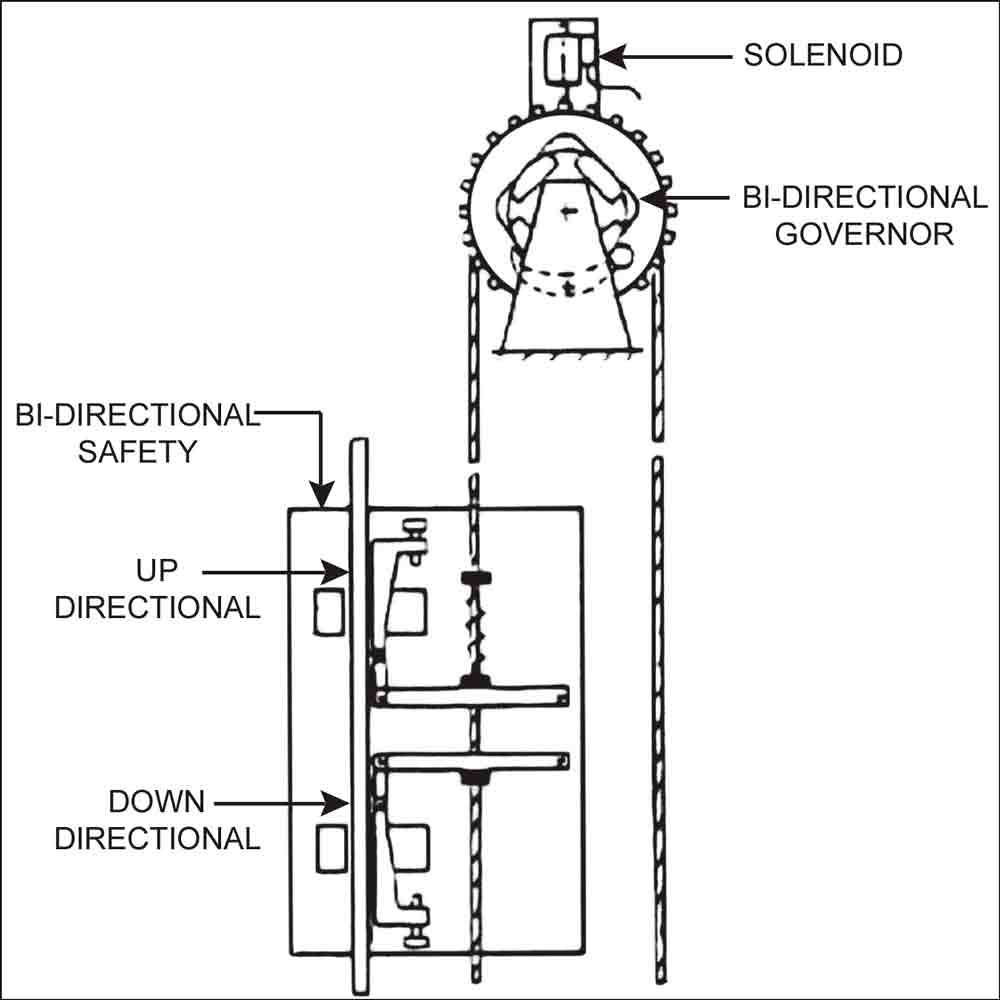

The early requirement in EN 81 was only for ACO protection. This was accomplished with manual rope brakes in China and bidirectional safeties in Europe. Both were strictly mechanically activated by newly designed governors. When UCM is required along with ACO protection, as in the U.S., Canada and the latest EN 81, these devices became somewhat impractical, either activating during a power failure, then requiring manual reset, or using battery backup to prevent activation and monitor the possibility of ACO and UCM.

Although a sheave jammer (brake) was used with limited success, a rope brake such as the Rope Gripper® is the main product used for A17/B44 requirements. During a power failure, it will simply stop the elevator without damage to the ropes. When power is restored, it will place the elevator back in service. Of course, if an actual fault occurred, the circuits would require a mechanic’s intervention to fix the problem and reset the device.

The Rope Gripper is basically a “dumb” device relying on another means for its operation. In Canada and the U.S., control manufacturers have been dealing with the circuits to activate and reset the Rope Gripper for years. This appears to be the best and least expensive method, because the control system knows exactly what the elevator is doing and can easily detect a fault. The addition of inputs, outputs and software adds little expense.

Many European manufacturers have decided to supply separate panels to activate their emergency brakes. While this may be easier in the short run, it is more expensive and does not provide as much flexibility. It does, however, make it easier to add these devices to an existing installation. In addition to redundancy and checking of door functions, the device can be installed on existing elevators, and, along with a Rope Gripper, protects against ACO and UCM.

Those in our industry who are part of the various code-making bodies are to be congratulated. They have noticed some areas where it is absolutely necessary to improve safety, and they have done so. The riding public is safer due to their diligence. However, knowing what we know about these dangerous situations, they have not gone far enough. A17.1, B44 and EN 81 are codes that apply only to new elevators, which are less likely to display these dangers. Our code writers have effectively shut the barn door, but the horse is already out, as older elevators represent the largest potential for accidents. A good case might be made that the older an elevator is, the more likely it is to display these problems.

I understand the difficulties of writing retroactive requirements, but it has been done before (in the case of Firefighter’s Service). If our industry truly has the safety of the riding public at heart, it could and should have a much bigger effect by making protection for at least door circuits, ACO and UCM mandatory for all elevators. This is an especially important concept for elevators because of their long life expectancy. The riding public expects elevators to always be safe. Our requirements should meet their expectations.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.