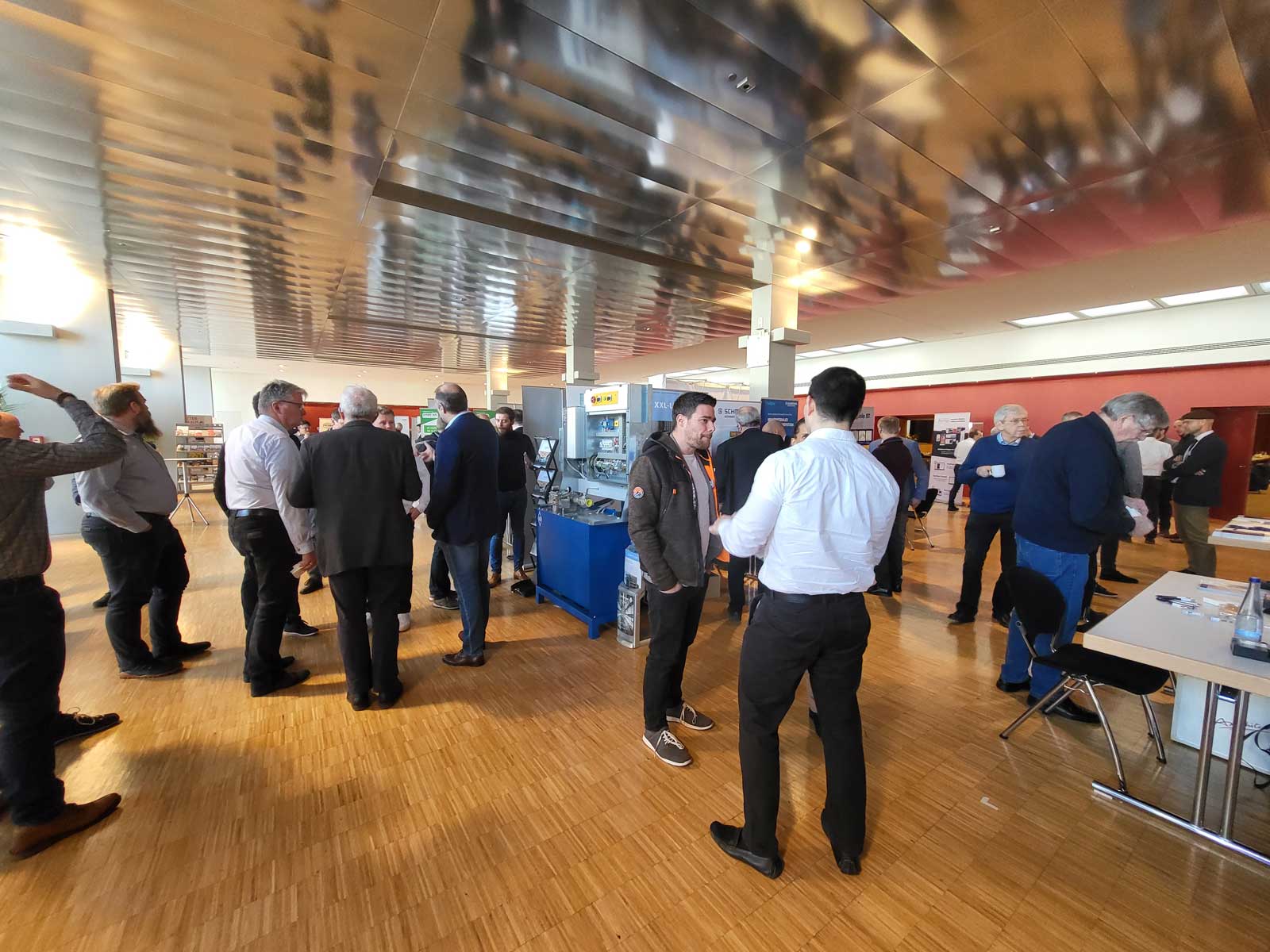

The 40th edition of the Heilbronn Elevator Days was held under the slogan “The Elevator in the 21st Century: sustainable, digital … safe and secure!” For two days in early March, around 270 people came to hear speakers and see the accompanying exhibition. The large foyer in front of the lecture hall was constantly filled with exhibitors and visitors. The exhibits were high-quality, manifold, diverse and large. All 13 lectures could be directly evaluated online in terms of content and presentation; the tool was also used for asking questions. In addition to the long breaks throughout the day, the evening event at Heilbronn University offered another opportunity for attendees to exchange experiences, as well as to get to know each other and cultivate old contacts.

Welcome by Prof. Georg Clauß, Technical Academy Heilbronn

Clauß was pleased the event was almost as popular after the coronavirus as it had been before. The level of attendance was even more pleasing since the university and academy are still largely offline after a cyberattack. Criminal investigators and the technical department have been working on restoring the university’s systems for months. A lack of online presence might have led to the event’s disappearance from the market.

Introduction by Klaus Dietel, TÜV Nord Systems, Conference Chair and Moderator

The organizers’ goal of 300 attendees was nearly reached. “We’re back and with new ideas, too!” said Dietel. The MeetLift recruiting event is still a delicate seedling. On the first afternoon, Elevator Days was open for young professionals to establish contacts with decision makers from potential employers. Dietal cited trends, including a shortage of young talent, sustainability, digitization, cyber and systems security, as well as rules and regulations.

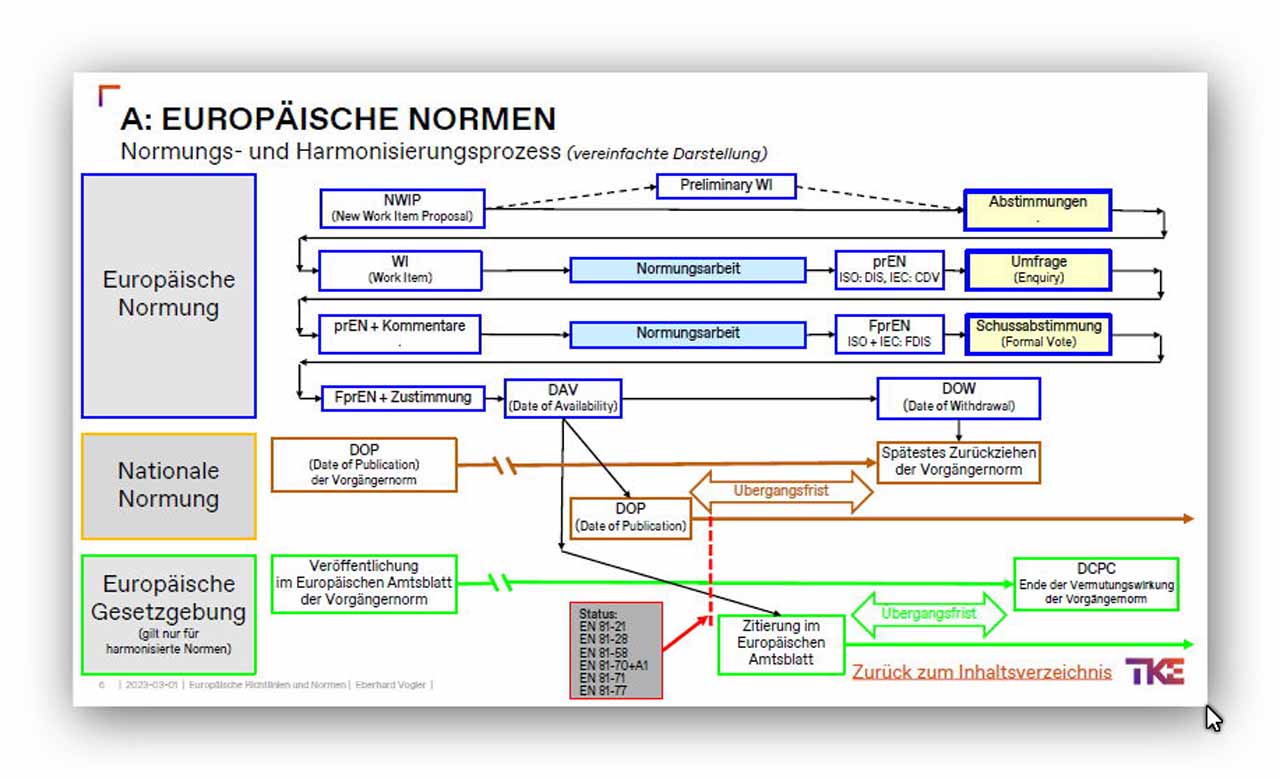

European Directives and Standards by Eberhard Vogler, TK Elevator (TKE)

Vogler gave this traditional opening lecture for the first time as the successor to Dr. Gerhard Schiffner. He opened with a detailed description of the standardization and harmonization process in Europe. The picture vividly shows the long, winding path to a harmonized standard as it is applied nationally, ensuring adherence to European legislation in the form of EU Directives. He went through the more than 30 pages of EN 81 and other standards in which there have been new developments in the past year or in which a change is expected in the coming year.

In detail, Vogler dealt with the status of work on prEN 81-76 dealing with passenger elevators for the evacuation of persons with disabilities. In autumn 2022, the paper had been rejected by Germany. Work is currently underway to classify the elevators. In principle, the building codes in Germany must be adapted so the standard can later be applied broadly.

In the third part of his presentation, he dealt with the status of the work on EN 8100-1/-2. He expects it to be published in the first quarter of 2023. This will be followed by the enquiry in the second quarter of 2023 and the formal vote in the second quarter of 2024. The standard will then be available from the first quarter of 2025. The transition period for Europe is expected to end in 2028; EN 81-20/-50 will lose its validity.

Relevant changes in EN 8100-1/-2 are to be found in the areas of doors, brakes, extension of inspection travel beyond the final landing, electrical safety devices, cybersecurity requirements and extended requirements for ladders. Relevant innovations can be found on alternative suspension means, platforms in the pit, vertical doors, flap door closures, hydraulically actuated brakes on traction elevators, automatic emergency rescue system and reduced rated load for traction elevators. Vogler concluded his presentation with a detailed look at the current status of work on the parts of ISO 81xx and other relevant ISO standards.

Sustainable Elevator Modernization by Frank Schmidt, S+ Schmitt+Sohn Elevators

To start, Schmidt defined sustainability: “The systems involved can withstand everlasting a certain level of use of resources without suffering damage.” In the case of elevators, for example, all 6.5 million systems in Europe would be renewed in “only” 65 years. He sees the need to act faster because of changes in building use and current energy considerations but, most importantly, because time has passed technology in terms of safety, design and technology.

Following this, he delved into the energy considerations based on the E4 study of 2010. The calculations were based on 4.5 million elevators in Europe, whose total energy demand was estimated at 18.4 TWh/a at that time. Hydraulic and geared elevators account for the largest share. The European Lift Association (ELA) is currently collecting fresh eco-data as a basis for decision-making.

If an elevator is not energy efficient, you could:

- Do nothing: simple, sustainable, but not energy efficient.

- Replace the elevator: conspicuous, probably biggest energy savings potential, but sustainable? Over a period of 65 years, this would result in an average savings of several 100 kWh per average elevator, with a high input of raw materials and energy.

- Modernize the elevator: conspicuous, but optimization of the energy savings to sustainability ratio is possible because many components are retained. Fewer structural adjustments with the use of resources like concrete are necessary. Noise and dust pollution, as well as the time required with usage restrictions, are lower. Overall, the solution is less expensive.

So far, safety has been the main driver for modernizations. In the future, Schmidt expects ecology and accessibility to be additional motivations. For this reason, ELA in its Working Group (WG) SAEL (Safety, Accessibility, and Energy Performance for Lifts) has collected measures for this purpose in the catalog “Synergy Achievements in Combined Measures for Improving Safety, Accessibility and Energy Efficiency in Modernizing Existing Lifts,” which, if possible, addresses all three motivators simultaneously. He concluded his presentation with an appeal for modernization, which he personally considers to be the most sustainable approach.

The New EU Machinery Regulation — Impact on the Elevator Industry by Thomas Kirsch, Central Office of the Federal States for Safety Technology (ZLS Zentralstelle der Länder für Sicherheitstechnik)

Kirsch began by presenting the regulation’s current status. The first draft was published in April 2021 and the compromise proposal in January 2023 (data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5424-2023-INIT/en/pdf). He expects final publication in the second quarter of 2023. Forty-two months after publication, the ordinance must be applied. Kirsch addressed important innovations in the ordinance: alignment with the EU’s New Legislative Framework (NLF), digital operating manual, adjustment of the scope of high-risk machinery, protection against corruption and definition of “relevant change.” The ordinance affects the industry in terms of placing products on the market. Specifically, technical documentation must be adapted. Risk assessment must be done before the design and construction of the elevator. Information Technology (IT) security must be considered. It must be checked whether it is a relevant change according to the new definition. There is a duty to provide information to national competent authorities. Under certain conditions, it is mandatory to involve a notified body (NB).

Understanding Elevator Safety: From 1854 to PESSRAL by Klaus Dietel, TÜV Nord Systems

As a historical introduction, Dietel quoted from the fifth Book of Moses from around the sixth century B.C.: “When you build a new house, make a railing around the roof so that you do not incur blood guilt if someone falls down.” Since industrialization, safety has become increasingly important. Today, it is established in the European legal framework, including standardization, with three main components: risk assessment for products, risk assessment for work equipment/work processes and a last-minute risk assessment for occupational health and safety.

Standards are written-down knowledge. A standards, for example DIN EN ISO 12100:2011, deal with basic safety standards: “How do I perform a risk assessment?” B standards like EN 349 and DIN ISO 60204-1 are safety groups standards that specify stereotypical technical devices/protective equipment such as “emergency stop.” C standards such as EN 81 are product-specific standards.

Historically, an early route to safety was oversizing. This was later joined by redundancy such as two ropes and diversity such as the safety gear, all with the goal of single-fault safety. Other safety components, such as shaft door interlocks or buffers, were subsequently anchored in the European regulatory framework, with the broader goal of multi-fault safety. Such assemblies with determined safety functions undergo corresponding conformity assessment procedures.

Through digitalization, this hardware-based safety is being displaced by so-called functional safety, which is software- and probability-based. As examples, he mentioned UCM protective devices, shaft positioning systems and complete control systems. Such systems are collected under the term PESSRAL (Programmable Electronic System in Safety-Related Applications for Lifts). Functionality is proven by testing institutions in accordance with relevant documentation. At present, another dimension is being added to system safety: security (interaction between the system and the outside world).

Elevator Industry as Industry of the Future: Demographic Change, Urbanization, Sustainable Land Use by Volker Lenzner, VFA-Interlift e.V.

Lenzner first introduced the small- and medium-sized industry Association VFA-Interlift e.V. with more than 240 members and its VFA Academy with around 50 trainings and more than 400 participants per year. With an increasing demand for elevators and escalators, mainly due to demographic change and urbanization, the shortage of personnel is also rising dramatically. Around 17,000 people currently work in Germany’s elevator industry.

All mechanics are lateral entrants because it is no longer an apprenticeship profession in Germany. They must be introduced to the industry and trained in elevator technique. For this reason, VFA Academy offers, among other things, further training with theoretical and practical parts. Since 2008, a certified continuing education series with a curriculum based on a VDI standard has been running successfully. Advanced courses and special topics, as well as sponsorships of conferences, round off the range of courses offered by VFA Academy.

One would like to see a European network of training providers and a mandatory level of training for different elevator jobs.

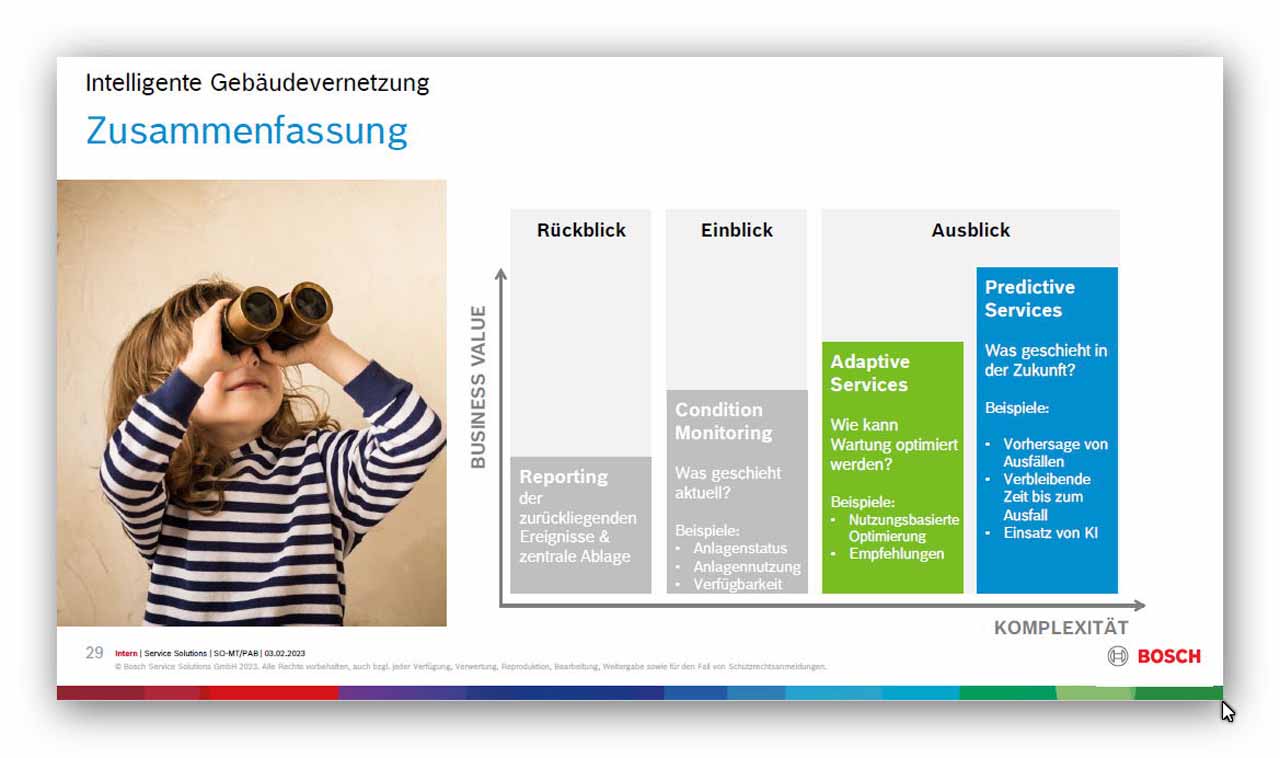

Buildings, Lift, Cloud – What Monitoring Can Achieve by Matthias Trautner, Bosch Service Solutions

Trautner tested the OpenAI software ChatGPT. The question “What can external monitoring do?” yielded an acceptable answer in terms of content and language, which he read out to start his presentation. Such tools could generally significantly shorten response times to inquiries about elevator malfunctions in the future, provided that the relevant information is imported by the manufacturers.

Trautner mentioned sustainability (climate-neutral buildings by 2050), digitization, a shortage of young talent with increasing order intake, creating new value-added services for residents and changing regulations as challenges for the real estate industry. Building owners and tenants face increasing Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) requirements and an increasingly hybrid working environment. The rise of hardware, software and services increases complexity, and with it the already lacking transparency in building data and building use. Isolated building control systems, mostly without monitoring, dominate building operations.

As a solution, Trautner sees a reduction in complexity combined with an expanded range of services based on data transparency and data availability using a distinctive monitoring system. This requires networking of the parties involved, as well as the integration of additional service providers. Trautner topped off his presentation with three examples revolving around retrofit, remote services and energy reporting. He also presented application examples from the Bosch portfolio: Robert Bosch Hospital, Viega Attendorn, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg. Over time, as business value increases, so does complexity, he observed.

Special Duty Elevators in Steel Construction – Aesthetics and Functionality by Franca Borzaga, Metal Working (Italy)

Metal Working produces the “dress of the elevator.” Users do not see the technology itself, but the outer appearance. In a video, Borzaga showed the steps required in the company’s steel construction of shaft towers. In detail, she presented two examples:

- In a three-year research project on structural systems, new connections for elevators were developed, prototypes built, and experimentally evaluated.

- The second project involved designing the steel structure for the elevator in the Colosseum archaeological park in Rome so that “people who may be wheelchair bound might enjoy the majesty of this monument for the very first time.“

Elevators and Cybersecurity: What It’s All About — How To Do It by Jörg Becker, TÜV SÜD Industrial Services

Becker began by asking “What is cybersecurity?” It is a made-up word composed of cyber (anything that has digital alterable data) and security (protection of technology from unwanted interference by humans). Attacks on companies’ IT technology are on the rise because the effort required by criminals is favorable relative to the payoff through data theft, extortion, compromising availability, creating hazards or destruction.

His next question was “How do I become cybersecure?” Tools for cybersecurity work at different levels. To identify and implement an effective approach, three questions are worked through sequentially:

- What do I want to prevent? Based on the defined protection goals, the affected components/systems of the elevator system are identified.

- What is my protection requirement? The various protection levels are defined in BSI and IEC standards, among others.

- How is my protection implemented? The guiding cybersecurity standard series is IEC 62443, which includes basics, security requirements for operators and service providers, as well as security requirements for automation systems and components. Realization begins at the time of placing on the market and continues into safe operation based on a risk analysis defined in IEC 62443-3-2 Risk Assessment Procedure.

What does the regulation say? The regulations are divided into two legal areas: “safe placing on the market” and “safe operation.” In the case of placing on the market, European Directives, as well as among others the Machinery Directive (MD), the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) and the Lift Directive (LD), have an impact, although these will only be made mandatorily prepared for cybersecurity in a few years’ time. Safe operation is based on the Ordinance on Industrial Safety and Health (Cybersecurity is here not explicitly mentioned, but is also not explicitly excluded) as well as EmpfBS 1115 “cybersecurity of safety-related measuring and control devices” and a new TRBS. Annex 2 of the Ordinance on Industrial Safety and Health describes the testing requirements for ZÜS (authorized inspection body), which therefore also includes cybersecurity.

In conclusion, Becker stated:

- Cybersecurity means protecting defined functions with digital elements against cyberattacks.

- Cybersecurity establishes a level of protection for the respective systems to meet defined protection levels, which leads to the necessary measures.

- Due to the increasing likelihood of cyberattacks that entail unacceptable risks, cybersecurity is increasingly becoming part of the regulatory framework at the national and European level.

Cybersecurity in the Elevator Sector – The New ISO 8102-20 and IEC 62443 by Frank Roussel, Schindler

Safety originates from industrial safety/operational technology (OT), while security originates from data security/IT. The objective of ISO/TC 178 WG12 for the development of ISO 8102-20 was to build bridges between IT and OT based on IEC 62443. The IEC 62443 series includes relevant process requirements for manufacturers and for owners, as well as relevant product requirements for manufacturers. Accordingly, ISO 8102-20 defines how IEC 62443 must be applied to elevators and escalators. In detail, it defines the functions and interfaces for which IEC 62443 is applicable, as well as the safety levels for the functions and their interfaces. It clarifies the scope of IEC 62443 for the life cycle of elevator products. Roussel then presented the contents of ISO 8102-20 chapter by chapter.

His conclusion was:

- Cybersecurity comes with a steep learning curve, but it is indispensable.

- Cybersecurity is not complicated but complex.

- Standardization is necessary to manage complexity.

- Good architecture can simplify implementation.

- Good preparation simplifies the implementation of future ordinances.

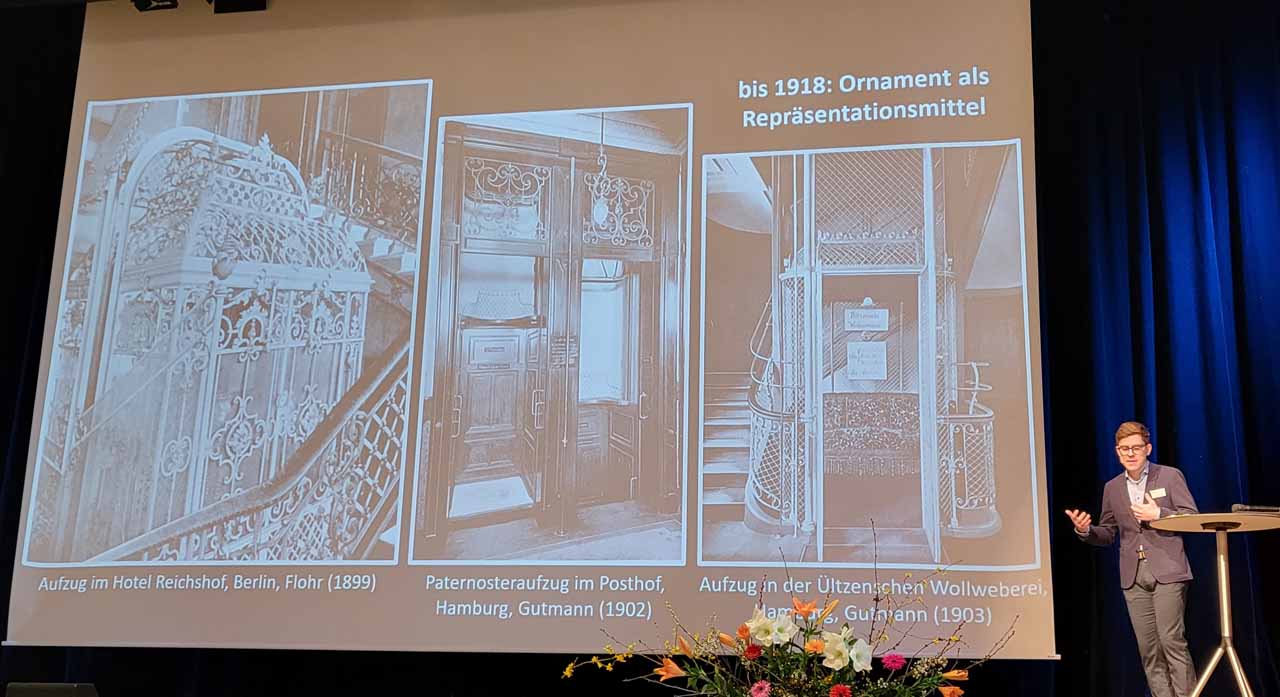

Tangible History – The Historical Elevator as a Living Monument by Robin Augenstein, University of Hamburg

Augenstein defined an elevator as historic if it is at least 30 years old. He began his considerations in 1890, when the electric drive was established. For engineers, he explained how historians and preservationists evaluate whether an elevator is something special and worth preserving. What is still existing today is more a matter of chance. The most frequently used elevators have often been modernized or replaced several times up to the present day. Company writings, on the other hand, offer the full range and starting points for evaluation.

In the early days, elevators were mobile places of representation:

- Until 1918 — Ornament as a means of representation: Technology was hidden under ornaments such as inlays, colored glazing or bronze casting to prevent fears.

- 1918-1950 — Material as a means of representation: aluminum, upholstery with leather or fabric, vitrified wooden cabin, polished brass, nickel-plated surfaces.

- 1950-1985 — Color as a means of representation: color photography, doors made of steel with varnish, baked varnish and anodized strips, plastic relief surface. Color was cheaper than different materials. Elevators offered an intense experience within a short time of use and provided a color accent in austere stairwells. Many cabins still exist today but are now covered with steel walls. Many light bulbs made technology interesting.

Hamburg has many monuments. Its Heritage Protection Act says: “scientifically research the monuments … to protect and preserve them … The city of Hamburg contributes to the costs of preservation and repair of monuments.” This also applies to permanently joint components such as elevators. Augenstein uses the passenger elevator in the Majolikahaus in Vienna, Austria, as an example of monument value: inseparable design unity of the elevator and surrounding architecture, notable artistic design of the furnishings, readability of social phenomena of the past, technical historical significance, outstanding historical significance (age record).

Preservation requirements often run counter to safety requirements, which is why negotiation processes are common to find a jointly supported solution. If necessary, additional reasons for preservation outside of historic preservation must be used, such as sustainability due to the enormous longevity and robustness of installed components. The prerequisites for successful preservation are comprehensible and well-founded technical planning, historical knowledge in the areas of technology, surfaces and design, qualified technical personnel and, last but not least, the owner’s willingness to invest.

Since 2020, Augenstein has been attending a Flügger commercial building project in Hamburg. Built in 1908, a paternoster elevator was originally installed to save time. The frequently resold building had been vacant since the 1970s, and the paternoster disappeared behind some drywall. This oldest known surviving paternoster in the world was uncovered in 2020. Only documents from the post-war period were preserved; the exact year of construction and the name of the manufacturer were missing. The search for clues led, for example, to the discovery of documents from the Hamburg Public Utility Company, which showed retrofitting from DC to AC around 1930. The company Wimmel & Landgraf from Hamburg-Uhlenhorst was identified as the manufacturer based on their cast steel rim patent from 1903. Conditions of preservation were documented, and repair possibilities sought. The lubrication system of the wooden guides of the cages was cleaned. And yet it moves!

PESSRAL in Practice – LIMAX33 from the Manufacturer’s Point of View by Stephan Rohr, ELGO Batscale

The first PESSRAL certification was awarded for Limax33RED with a separated safebox. This makes it applicable according to EN 81-50 section 5.6.3.4.b. Software and hardware testing verifies all measures selected from Tab B.1 and B.2, as well as from Tab B.7 by fault simulation.

The first IEC 61508 certification for Limax33CP with an integrated safebox has also been obtained. The demands on the product have increased, so that 4-h tests with TÜV were specified and documented.

Greater flexibility in development leads to more functionality in the sensor. Rohr went into more detail about the creation of the specifications and documentation. He presented the Limax sensor series with its various safety functionalities, e.g., UCM, various safety gears and overspeed trippings.

PESSRAL in Practice – The User’s View by Anna Künzel, TÜV SÜD Industrial Services

Safety runs through a life cycle starting with conception and ending with decommissioning. The path to type approval covers the first three steps: design, development and validation. PESSRAL elements are planned based on TRBS 1115 safety-related measuring, control and regulating devices and tested in accordance with TRBS 1201-4 testing of elevator systems. EK-ZÜS BA 015 has defined a process flow for the testing of safety-relevant measuring and control technology devices in accordance with TRBS 1201-4 by the ZÜS.

MeetLift – Young Talent in Companies

In this first attempt to attract future employees to the elevator industry, around 15-20 participants from the region met after the lunch break on the first day. The lecture room was at capacity — plus rows of chairs in the back.

Throughout Heilbronn Elevator Days, staff shortages were mentioned as an important issue during presentations and conversations during breaks, making the MeetLift forum even more valuable. Other challenges to recruitment, such the industry’s visibility and image issues (attention is drawn mostly when something has gone wrong) and lack of concentrated resources to attract new employees, as the industry is dominated by small- and medium-sized enterprises, were also discussed.

Further pursuit and expansion of the MeetLift initiative were frequently requested by participants and speakers alike and addressed several times.

Besides inviting potential future technical staff to participate, the organizer also offered exhibitors stand tables in exchange for giving talks. This offer was accepted only by Franca Borzaga (FBO), executive board director of Metal Working in Pergine Valsugana, Italy. Your author (USB) spoke with her on the topic of “young talent in companies.”

USB: Tell us about your company and yourself, Ms. Borzaga.

FBO:Up to 75% of Metal Working is building “dresses” for elevators, i.e., shaft towers mostly for very special buildings in Italy and for the “Big 4” abroad. I oversee exports, having worked for many years in Germany, too. About 25% of what we do is industrial filters. In 2008, I founded the company with three partners. Today we have 45 employees (23 of them in production) from Italy, Romania and Senegal, among other countries.

USB: It is becoming increasingly difficult to find personnel seeking a career in the elevator industry. What do you think is the reason?

FBO: In general, it is hard to find any engineers. Young people today first check what a company has to offer. Unfortunately, large corporations offer more. We, on the other hand, offer further education and international research.

USB: Tell us about the young people employed at your company.

FBO: Eighty percent are very satisfied with the work. We are a good team. Many employees have also been with us for a long time. They are our greatest company asset, and we offer perspectives for the future. With consultants, we have selected eight people to lead our company into the future. In the first year, we have already made a lot of progress. The younger ones are slowly taking on more responsibility. Such prospects make jobs attractive to the next generation. What they find difficult is to be patient along the way. Such personnel developments don’t happen after just one month in the company.

USB: Aside from events such as Heilbronn, what other activities do you undertake to recruit personnel?

FBO: Most of the time, we bring people in for the first time through personnel leasing agencies instead of hiring them directly. This has become a very attractive route for us. Those who like it here and who we like will stay, but some will not.

USB: Are there any other approaches?

FBO: Yes, I have already organized two evenings with universities. Also, we now gladly integrate motivated migrants. For this purpose, the Autonomous Province of Trento, through the companies of the region, offers programs over two years’ duration to provide apprenticeships for migrants. These are even supported by reduced social contributions.

USB: Thank you, Mrs. Borzaga, for your frank answers from the perspective of a medium-sized European entrepreneur.

Bosch Industry Dialogue

After a two-year hiatus due to from the coronavirus, the traditional Bosch Industry Dialogue took place again the evening before the Heilbronn Elevator Days. Nearly 60 participants attended — as many as the 2020 event, already under pandemic conditions. About one third of attendees were completely new faces, about one third visit every few years and about one third belong to the regulars. The visitors were welcomed by Bodo Adamus, senior sales manager at Bosch Service Solutions. Two presentations followed:

Two-Senses Emergency Call – Current Status of the Standard and Possibilities of Realization, Jörg Hellmich, ELFIN Technology

Hellmich started with a browse through the standards, in which one expects to find something on the subject, but does not, because only framework conditions are set there. Requirements with detailed technical instructions can be found in ASME A17.1-2019. In addition to the voice channel, it must be possible to send an emergency call in another way, namely nonverbally (two-senses principle). Hellmich presented solutions from his company to meet these requirements. He assumes that the two-senses emergency call will find its way into EN81-xx when it is revised.

Responsibilities Around the Elevator – From the Perspective of the Operators and the Elevator Companies. As Jan König, Ing4Lifts, Was Indisposed, Bodo Adamus Took Over His Part of the Presentation.

Operator: As a basis, Adamus presented the status of the legal regulations and the Technical Rules for Operational Safety (Technischen Regeln für Betriebssicherheit TRBS). He derived the duties of the operator before and during the commissioning of an elevator.

Elevator company: This part of the presentation focused on occupational safety and, marginally, on the safe product and its maintenance. Adamus outlined the basics from the Basic Law and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. In detail, he went into information from the German Social Accident Insurance (Deutsche Gesetzliche Unfallversicherung DGUV). This regulation is available for free download at publikationen.dguv.de/regelwerk/dguv-informationen. Requirements specifically relating to safe products are also found in the EU Lift Directive and EU Machinery Directive. DIN EN 13015, VDI 3810 Part 6 and a VmA document regulate the maintenance of elevators and escalators.

The subsequent networking dinner provided sufficient opportunity for professional and personal exchange.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.