Darling Brothers

Aug 1, 2018

The past alludes to the present with the story of an early Canadian manufacturer.

The development of the elevator industry in Canada followed a pattern common to Europe and the U.S. Companies that focused solely on elevator manufacturing were established, as were those that included elevator production within a broad range of other mechanical equipment. The latter group includes Darling Brothers, Ltd. An examination of this company, from its founding in the late 1880s and its initial growth into the 1920s, illustrates the character of the Canadian elevator industry in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Darling Brothers was founded in 1888 in Montreal by Arthur J. Darling (1863-1915), George Darling (1866-1925) and Francis “Frank” Darling (1867-1963). A fourth brother, Edward Darling (1873-1956), joined the company in 1901. The three elder brothers learned engineering and manufacturing through the apprentice system, working in various trades in Montreal. Edward was the only one to pursue a university education, graduating from McGill University in 1894 with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. The business became a limited liability company in 1906, with Arthur serving as president, George as vice-president and Edward as secretary-treasurer. (Frank left the company at this time.) In 1888, the company occupied a small building approximately 2,400 sq. ft. in size. By the early 1920s, it owned four contiguous buildings totaling more than 100,000 sq. ft., with each building dedicated to a specific function: showroom, iron works, assembly plant, and inventory and stock.

Darling Brothers manufactured a wide range of products, including appliances, pumps, governors, lubricators, stair treads, elevators, escalators, dumbwaiters, heaters, hoists, valves and filters. Passenger and freight elevators were among the first items manufactured after the company was founded. By mid December 1888, Darling Brothers described themselves as “Engineers, Machinists & Brass Finishers (and) Manufacturers of Hand, Steam and Hydraulic Elevators.”[1] In 1904, it added electric elevators to its product line.

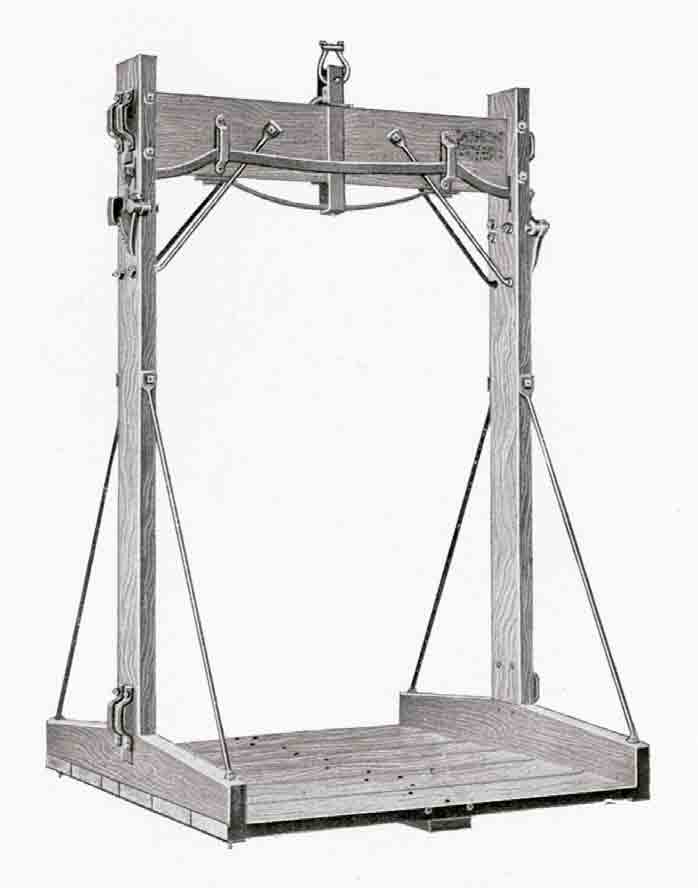

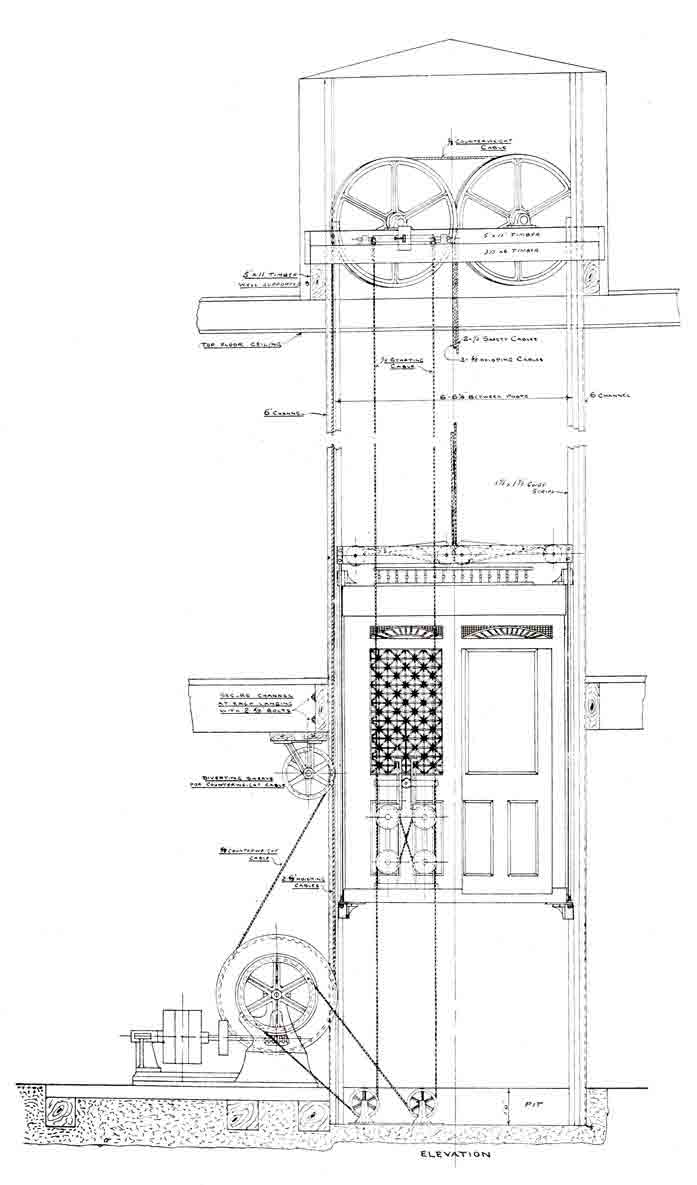

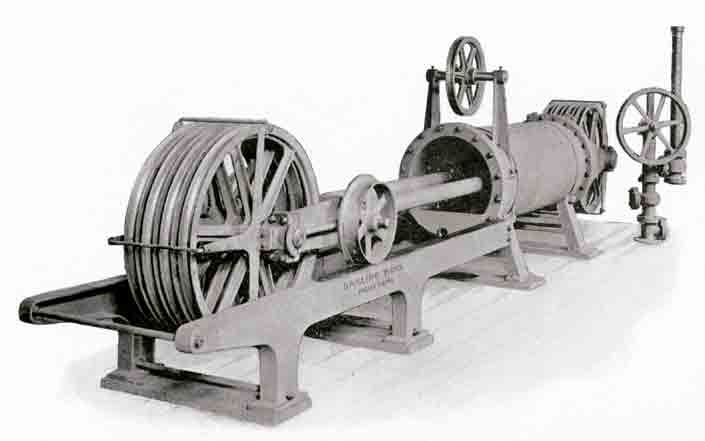

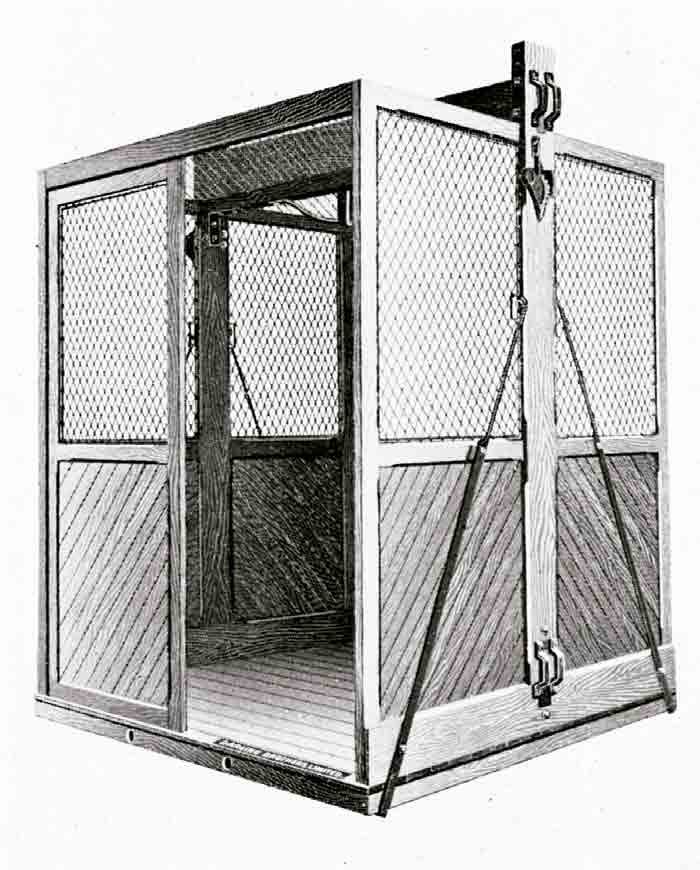

In 1914, the company published the fourth edition of a catalog titled Elevators for Passenger and Freight Service. The 32-page catalog included 23 illustrations, and described hydraulic, electric and belt-driven freight and passenger elevators; hand-powered elevators; ash hoists; and dumbwaiters. The freight-elevator systems were typical belt-driven machines (mounted on the floor or ceiling), which elevated either open-platform or enclosed cars. (Figures 1-3). These machines were described with the same hyperbole (with the bold text as appears here) found in American catalogs of this era:

“These machines have been in constant use for many years, for the best class of freight elevators. . . and we have yet to hear of the first breakage or accident to one of them. They can be belted direct from as line or counter shaft in a manufacturing building or run by a separate electric motor. Also fitted with a slack cable-stop, to prevent accidents from unwinding of cables. No expense or pains are spared to render these machines strictly first class in design, workmanship and material, and for noiseless running and durability they have no superior.”[2]

The reference to the use of electric motors is interesting in that it is doubtful Darling Brothers manufactured these motors. Thus, it would have relied on an outside supplier.

Evidence exists that the company, in addition to manufacturing products of its own design, operated as agents licensed to manufacture and sell products designed by other firms. At the same time, it proudly proclaimed its independence in elevator design and manufacturing. In April 1904, the company published the first of several notices on this topic: “Notice to manufacturers and owners of buildings. We have not been bought out by any ‘trust’ but are still in the elevator business. Estimates for new elevators and repairs will receive our prompt attention.”[3] The term “trust” referred to Otis, which, in the early 20th century, was completing its almost wholesale acquisition of regional elevator manufacturers in the U.S. In 1904, Otis expanded this activity to Canada, and it entered into negotiations to acquire Fensom Elevator Co. of Toronto. Fensom, founded in 1870, was Canada’s oldest elevator manufacturer. The merger, completed in 1905, resulted in the creation of Otis-Fensom Elevator Co.

Darling Brothers’ notice proclaiming its independence reinforced, if only by inference, its status as a Canadian elevator manufacturer. The introduction to its 1914 catalog reaffirmed this independence and the company’s commitment to elevator production:

“It has always been important when contemplating installing an elevator, to take into consideration the standing of the firm from whom you purchase same. We have been manufacturing elevators for the past 25 years, and during that time, our business has steadily increased. A number of companies have experimented in the manufacture of elevators, and, at the end of two or three years, have discontinued this special line of business, on account of same not being profitable. This naturally places the users in a most unsatisfactory position, for the reason that it is not possible to secure prompt delivery of duplicate repair parts, and, eventually, the elevator machine is consigned to the scrap pile. We make it our business to carry in stock duplicate parts of all standard elevators, as illustrated in this catalog, and under ordinary circumstances, we can ship repair orders the same day as they are received.”[2]

However, as will be seen, the company’s efforts to resist American incursions into its portion of the Canadian market eventually yielded to commercial realities.

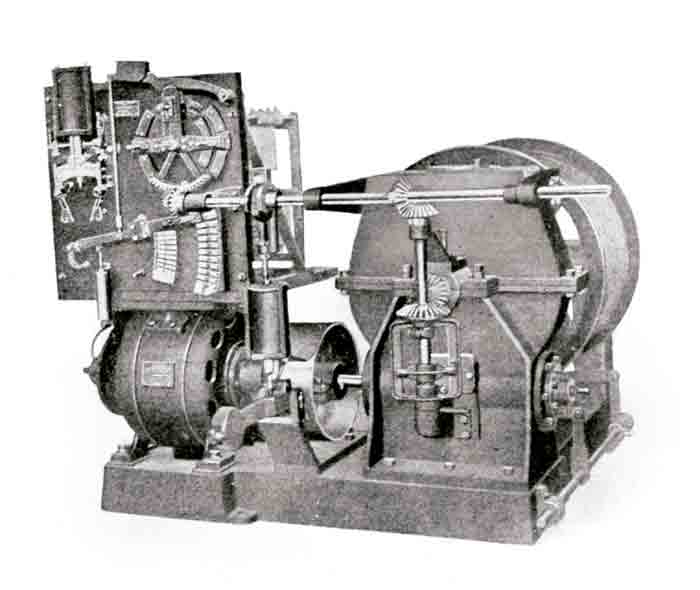

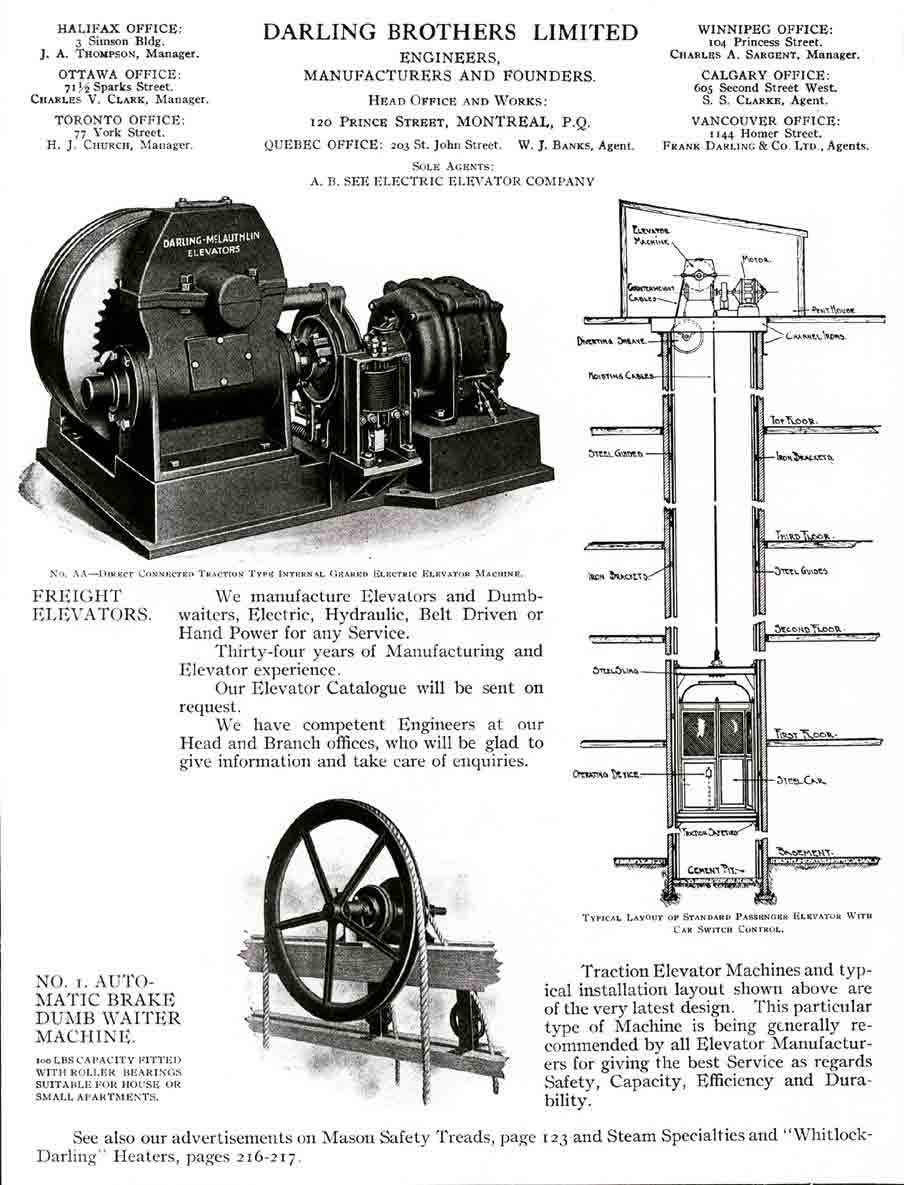

The electric elevators featured in Darling Brothers’ 1914 catalog included a direct-connected machine and a system that employed a belted connection between the electric motor and elevator. The operational flexibility of the direct-connected machine reflected the relative “newness” of electrical machinery during this period (Figure 4):

“These machines are suitable for either alternating or direct current, and can be fitted with button control, electric car switch, hand wheel, or shipper rope. The machine is of the worm-geared type, with direct, coupled motor, gearing and drum mounted on the same base. The machine is provided with bronze-rim worm gear, driven by [a] steel worm, and [a] worm shaft made in one solid forging, accurately turned and cut. Both worm and gear run in oil in entirely closed dustproof case. The winding drums are accurately turned and grooved for the cables. The machine is to be constructed so that the motor armature may be quickly removed without dismantling the elevator machine. The brake-wheel, which also forms the coupling between the armature and the worm shaft, is secured in such a manner that it cannot come loose.”[2]

While Darling Brothers reported it had “a number of these machines in successful operation,” by contrast, it stated it had a “large number” of its belt-driven electric elevators in operation.[2]

The company specialized in belt-driven freight elevators, and its extension of this technology — and experience — to passenger elevators is understandable. A production bias toward this machine type is evident in the inclusion in the catalog of a detailed drawing of a belt-driven electric passenger elevator (Figure 5). The text that accompanied this image also described the operational superiority of its electric belt-driven passenger elevator:

“[This] elevator [is] fitted with [a] large drum, gravity safety apparatus and handwheel operating and controlling device. This type of elevator costs less to install than the direct-connected elevator, can be operated with 50% less power, and the cost of maintenance is very much less than the direct-connected elevator.”[2]

The company also manufactured direct-plunger hydraulic machines for freight use and horizontal hydraulic machines designed for freight or passenger use (Figure 6). Lastly, it also built hand-powered elevators. These elevators included a hand-powered passenger elevator described as suitable for use “in residences as an invalid lift, as it can be raised or lowered by the passenger.”[2] Darling Brothers was not alone in manufacturing residential “invalid lifts”; however, the prospect of someone with mobility issues or other physical challenges being asked to provide the motive force to power an elevator is intriguing (to say the least).

The same year Darling Brothers’ catalog was published, 1914, also witnessed the establishment of McLauthlin Elevators, Ltd., in Montreal. This new firm was, in effect, a branch office of George T. McLauthlin Co. of Boston, a well-known regional elevator manufacturer. Between 1914 and 1921, Darling Brothers and McLauthlin developed a business relationship that resulted in the creation of Darling-McLauthlin Elevators. The new company appears to have operated as a subsidiary of Darling Brothers and may have been established solely to produce traction elevators. This supposition is supported by a Darling Brothers advertisement that appeared in 1922 (Figure 7).

While the advertising copy does not mention Darling-McLauthlin, the company name is clearly visible on the side of the traction machine, and this image matches those used by George T. McLauthlin in contemporary American advertisements. The advertising copy does, however, state that Darling Brothers served as the “sole agent” in Canada for A.B. See Electric Elevator Co. of New York.[4] Unfortunately, no details regarding this business arrangement have come to light. It may be that Darling Brothers chose to market the A.B. See machines and the McLauthlin traction machines so it could focus its design and manufacturing efforts on belt-driven freight elevators. This idea is supported by a series of illustrated advertisements published in 1918 that depicted freight elevators in various settings. The advertisement copy focused on elevator safety, with overt references to the importance of preventative maintenance.

The parallels between Darling Brothers’ machines and their American counterparts serve as a reminder of the ease of industrial communication during this period, which was made possible by technical journals, engineering journals, manufacturers’ catalogs, etc. The cross-border activities of American companies, initially seen as an unwelcome inclusion by Darling Brothers and later, apparently, accommodated as part of its corporate strategy, also serve as a reminder — 100 years later — that industrial relationships and trade between neighbors has always been a complex undertaking.

References

[1] Darling Brothers, Ltd. Advertisement, The Montreal Gazette, December 15, 1888.

[2] Darling Brothers, Ltd. Elevators for Passenger and Freight Service (1914).

[3] Darling Brothers, Ltd. Advertisement, The Montreal Gazette, April 4, 1904.

[4] Building and Engineering Catalogue 1922 Edition, Toronto: Specification Data, Ltd. (1922).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.