DC to AC Migration

Jan 6, 2023

A conversation with KONE Americas Vertical Market Business Director Dan Walsh

KONE announced in September 2022 it would retire its ReSolve with Unity drive, effective immediately. No longer modernizing older DC gearless machines, the manufacturer now offers machine replacements using newer AC technology. When the move was announced, KONE Americas Vertical Market Business Director Dan Walsh (DW) explained the drawbacks of DC technology, including braking systems that fail to meet the latest safety codes and the likelihood of costly repairs. On the flipside, benefits of AC gearless include increased energy efficiency, lower long-term maintenance costs and improved safety, he said, laying the groundwork for customers to “future-proof” their buildings and extend VT systems’ lifespans, not to mention save money and reduce risk. Worn traction sheaves on DC gearless machines typically need costly replacing or regrooving, and these machines could potentially expose property owners to higher legal risks and unhappy tenants due to prolonged equipment downtime. Further, KONE pointed out, skilled technicians and compatible parts for DC gearless machines are dwindling.

Walsh explained to your author (KW) that, despite the seeming abruptness of the September announcement, KONE has been working toward the transition from DC to AC for nearly a decade. He recently took the time to talk to her about the journey.

KW: Please provide a little background on KONE and DC gearless machines.

DW: KONE came out with the machine-room-less (MRL) elevator in the late 1990s. When it originally launched, people said it would mean the end of the hydraulic elevator in new construction. In large part, the MRL elevator has done just that. A component of the MRL is the gearless machine, and you started to have all this AC gearless technology proliferating in the marketplace. There was a natural transition into the modernization business, as well. So, everything that was being built new was AC, but you still had these older DC machines that were out there. They’re typically in higher-rise, higher-speed elevator systems. As the market transitioned to almost exclusively AC, you started to see a natural dwindling of spare parts, expertise and shops able to handle rebuilding DC machines. For KONE, it made more sense to have a common technology platform across the board more focused on the AC gearless part of the business.

Around 2013, there was basically only one manufacturer of DC drives (Magnetek). KONE developed a new DC drive with Magnetek, but the technology supply and training issues were just too much to handle. So KONE made the decision globally about eight years ago to stop selling DC drives.

KW: Have customers been on the same page in terms of seeing DC going the way of the dinosaur?

DW: It took a little while for the market to catch up. Part of that is if you look at major cities like NYC, Chicago and San Francisco, there is a pretty significant number of DC gearless equipment. Regardless, we saw this trend [from DC to AC] as an organization, and we prepared for it. We prepared installation technology where we are able to take these larger [DC] machines apart and take them out of a building efficiently. If you went into some of these machine rooms, it almost looks like the building was built around the elevator. Access and removal were challenging, but I would say over the last half decade we’ve become much more efficient at it. So, this is not something we walked into backward. We were very forward-thinking. KONE has always been a technology innovator, and we always look to be one step ahead of the market in terms of what the future looks like and what’s best for a building in terms of energy efficiency, ride comfort, safety — all of those things.

KW: Was KONE ahead of the curve?

DW: Probably, but it’s not a position we are uncomfortable with. We feel like we have the product offering and all of these methodologies in place to be competitive and do the right thing for our customers in terms of future-proofing their buildings with today’s technology.

We are well into the thousands in terms of number of units we’ve converted from DC to AC, as well as really the entire traction machine portfolio.

KW: Are customers amenable to the shift?

DW: More often than not, yes. We’ve been very specific in terms of the reasons we’re doing this. If I could show you our trend line, it’s probably curving upward at a 45-degree angle or better in terms of the number of machine replacements we’ve done over the last five-six years. We’ve seen significant growth. We’ve never regressed in the market with machine replacements for probably more than five years during the last decade or so. We are well into the thousands in terms of number of units we’ve converted from DC to AC, as well as really the entire traction machine portfolio. We are even replacing geared machines with AC gearless.

KW: Which regions of North America have the highest concentrations of DC gearless machines?

DW: As I said earlier, it would be your older, larger cities like NYC, Boston and Chicago. I had mentioned that elevators with these machines go higher and faster, so if you think of a city like Washington, D.C., that has architectural height limits because of the Washington Monument, there are not going to be as many DC gearless machines because they just don’t need that type of duty range.

KW: Please elaborate on how older DC gearless machines fail to meet the latest safety codes.

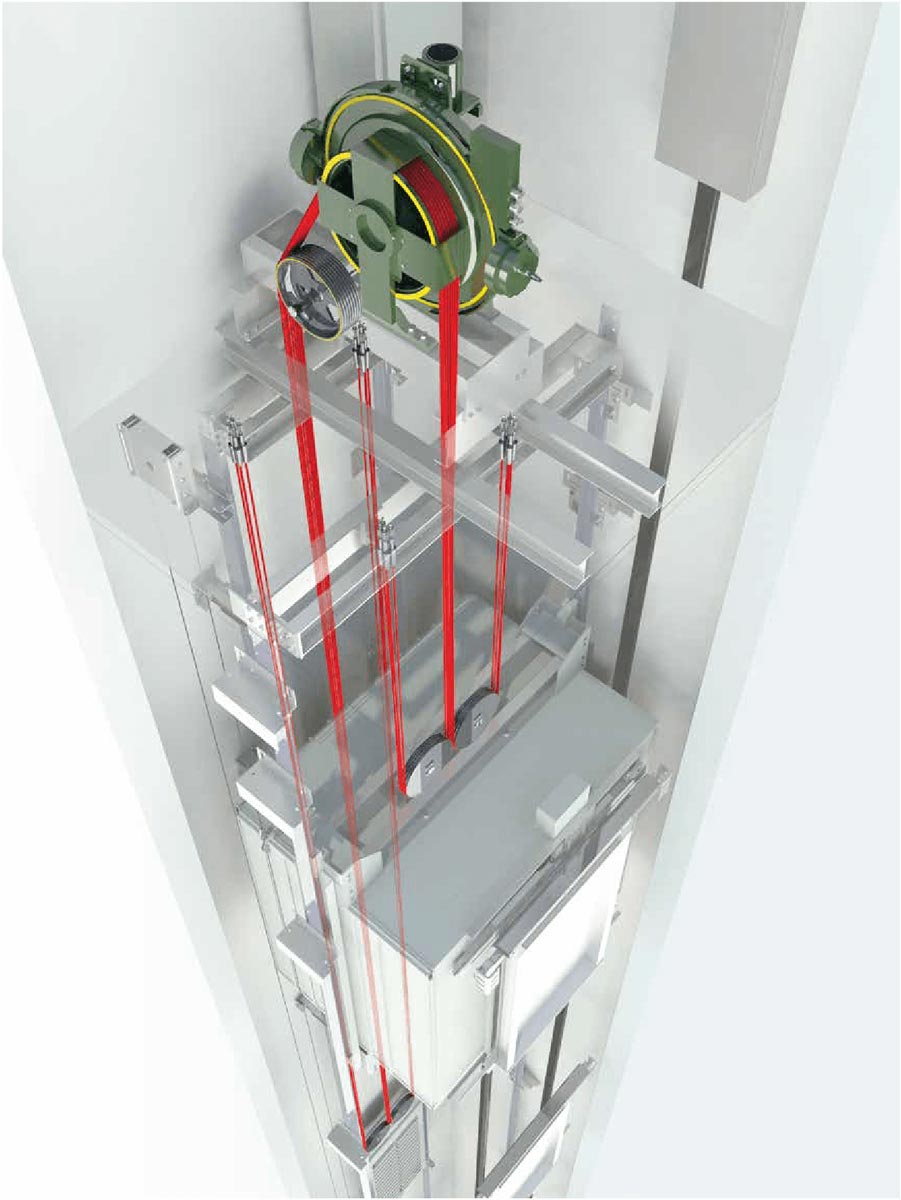

DW: Part of it is that DC machines are not built for the rope grippers that are there to stop unintended motion of the elevator. In rope grippers, there are two brake arms on the machine, each able to hold 125% of the machine load. With DC gearless machines, you have to retrofit a rope gripper into sometimes a 40-, 50- or 60-year-old machine. It’s not an industrialized application. It’s something that you really have to put some engineering thought into. You also have to look at space constraints in the machine room. You have to make today’s technology work with yesterday’s technology. Whereas, with today’s AC gearless machines, it’s part and parcel of the platform itself. AC gearless machines come out of the factory code-compliant.

With AC gearless machines, the power that we return to the grid is one, free, and two, generally cleaner than the power that comes from the power company.

KW: What is the price differential between repairing a DC gearless and AC gearless machine?

DW: It depends on the scope of work that needs to be done on the DC gearless machine. There are times when it is cheaper to just replace the DC machine (with AC gearless) because what you are trying to do in terms of bringing an older machine up to 2022 technology means a significant amount of work. The drive that is going to be added to modernize an older DC machine today wasn’t even conceived when that machine was designed. It was never designed to work with a modern drive that communicates with significantly faster speed. It expects, when it “tells” the machine to move, that that happens immediately. Current draws are higher, and the wire gauges in the older machines may not be sufficient to support that. You could end up spending US$50,000-US$60,000 to upgrade an older machine. It’s really just dependent on the customer’s intention for the building. Often, if they are going to hold onto a property, they are going to go ahead and make that investment for replacement. They see it as future-proofing their building.

KW: How are AC gearless machines more energy-efficient than DC gearless machines?

DW: AC gearless machines take only what they need in terms of power from the main line coming into the building. They also produce regenerative power, which is power that is naturally pushed back into the building’s power grid that can be used by other systems driven by electricity. With AC gearless machines, the power that we return to the grid is one, free, and two, generally cleaner than the power that comes from the power company. It’s kind of the gift that keeps on giving.

KW: It sounds like a no-brainer. Has there been any resistance?

DW: There are people who will tell you [DC gearless machines] will last for 100 years or more. I’m not convinced of that. There are some pieces and parts of those machines that are extremely difficult to get, and 100 years is an extremely long time. The drives that are designed for that system today you have to do a massive amount of work on to bring them up to an acceptable level. What would happen with the next generation of drives? As far as the market goes in terms of DC drive manufacturers, there is only one out there [Magnetek]. They do a really good job with it, but if something ever happens to them, what are you going to do?

About Dan Walsh

A resident of Wake Forest, North Carolina, Dan Walsh is no elevator industry newcomer: Like many in the industry, he grew up in the business. His father owned a consultancy in NYC, and Walsh began working with his dad when he was still in high school. Upon graduation, he stayed with the family business for about six years before moving on to train at Montgomery Elevator (acquired by KONE in 1994). After several years with Montgomery, Walsh moved to the supplier side, going to work for elevator cable specialist Draka, now part of the Prysmian Group, managing commercial sales worldwide. When he left Draka in 2008, Walsh returned to KONE as operations manager, modernization, before moving to his current role. “So, I basically handle everything from sales generation to technology applications to estimating to customer interaction and delivery,” Walsh says. “I am also involved in handling our smart building technology — things like mobile apps to call an elevator or elevator-robotics integrations.”

Along those lines, Walsh told your author about a KONE robot-elevator integration at a Chicago hotel from several years ago that is still going strong. The hotel’s service robot is used to deliver small items like bottles of shampoo or tubes of toothpaste to guests. “Every person that walks in wants to take a picture with the robot,” he said. “It’s the best advertising the hotel ever had, and that’s exactly why they did it.” Another, more serious — but no less interesting — KONE elevator-technology integration was at the Craig H. Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital (for quadriplegics) at the University of Utah, where the OEM used an application programming interface, or API, to integrate patients’ “sip and puff” tubes — assistive technology used to send signals to a device using air pressure by “sipping” (inhaling) or “puffing” — to call an elevator. But those are stories for another day.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.