Patents provide insights into early operation concerns.

Standard phrases or terms in the modern vertical-transportation (VT) industry have equally standard definitions. One such term, elevator alarm, is usually defined as a means by which a person who becomes “trapped” in an elevator car signals for assistance. This investigation began as a search for the first “elevator alarm.” A survey of the American patent record revealed 10 elevator patents, awarded between 1870 and 1890, with the word “alarm” in their titles. None of these patents addressed the issue of elevator entrapment. They were concerned with what was happening while the car was moving and/or stopping; the perceived need to provide a means to signal that a car had (inadvertently) stopped moving appears to have originated in the early 20th century. The rationale for 19th century elevator alarms, as expressed in the patents’ text, provides insights into concerns about elevator operation during this period. Additionally, given that none of the inventors involved had direct links to the VT industry, their concerns may be understood as being, perhaps, also shared by other users of this new means of transportation.

The application for the first patent, Benjamin Howard’s Improvement in Alarms and Indicators for Elevators, was filed in September 1873, and the patent was awarded the following year. The “object” of his invention was:

“To provide for elevators or hoisting apparatus used in hotels, etc., an alarm attachment and indicator by which the engineer may be enabled to know the position of the ascending and descending cage or car, and whereby he will be warned if such car exceeds in its motion the limits within which such motion is to be confined.”[1]

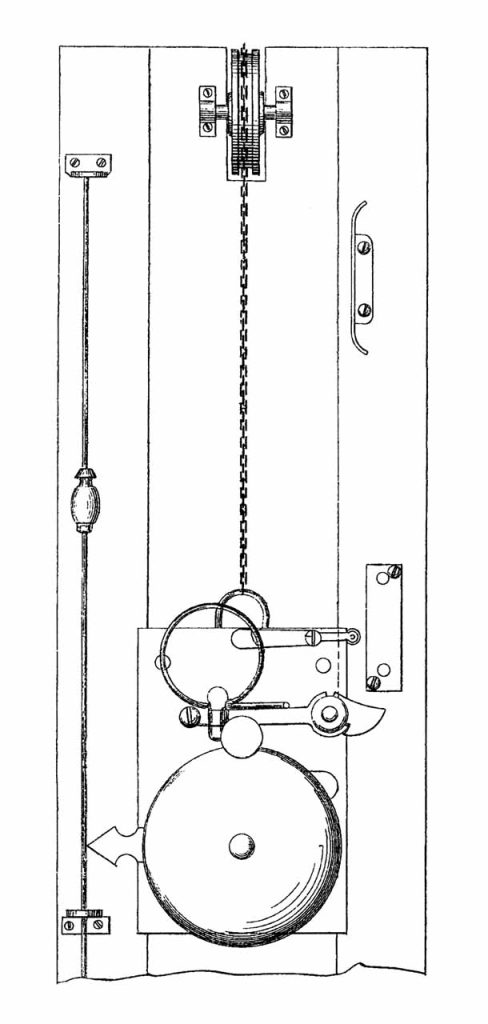

Howard’s design consisted of “a miniature representation of the elevator-frame and cage” within which moved an arrow that indicated the car’s position (Figure 1). The arrow was connected to a bell that rang once each time the car passed a floor indicator, and which would ring continuously if the car was “lifted beyond the proper height.”[1] While he claimed that movement of the bell and arrow would be “proportionate” to that of the actual car, Howard failed to describe how his device would be linked to the elevator such that it would accurately mirror its movement. Nonetheless, Howard conceived one of the first remote monitoring systems, which also functioned as an overtravel alarm. Of course, the fact that the alarm would have sounded in the engineer’s office, instead of the car, would likely have not prevented an accident, but simply have indicated that one had occurred.

In 1883, Amos Nickerson patented an alarm system attached to the side of the shaft and activated by the car’s motion.[2] An alarm bell was located near each floor level such that the arrival or departure of the car rang the bell. According to Nickerson:

“It not unfrequently happens that persons are injured or killed by being struck or crushed by an elevator while it is in movement, the accident generally resulting by reason of the person or persons not having sufficient warning of the near approach of the elevator to get out of its way.”[2]

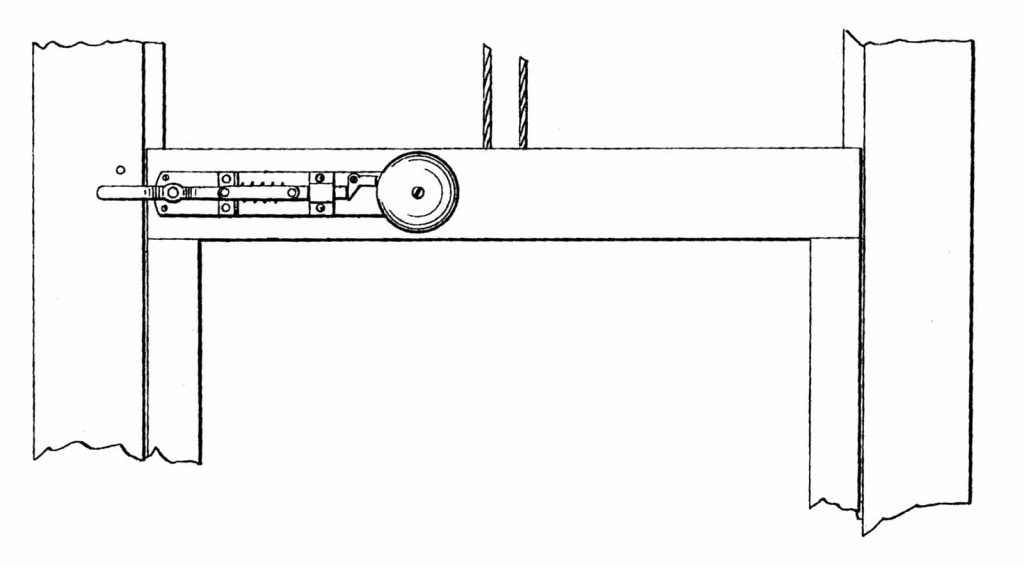

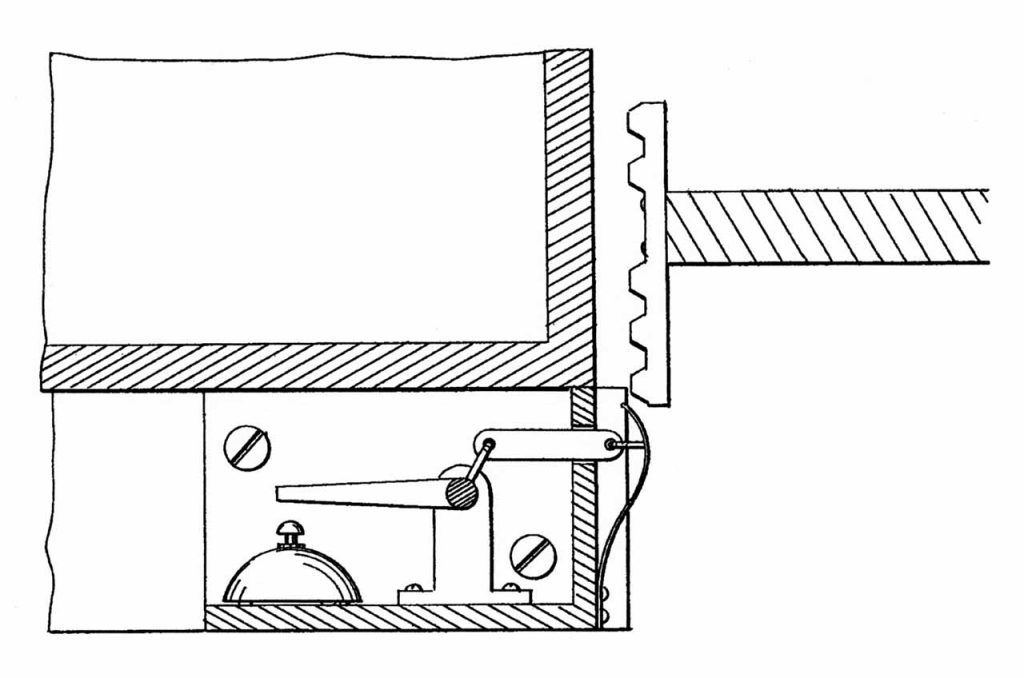

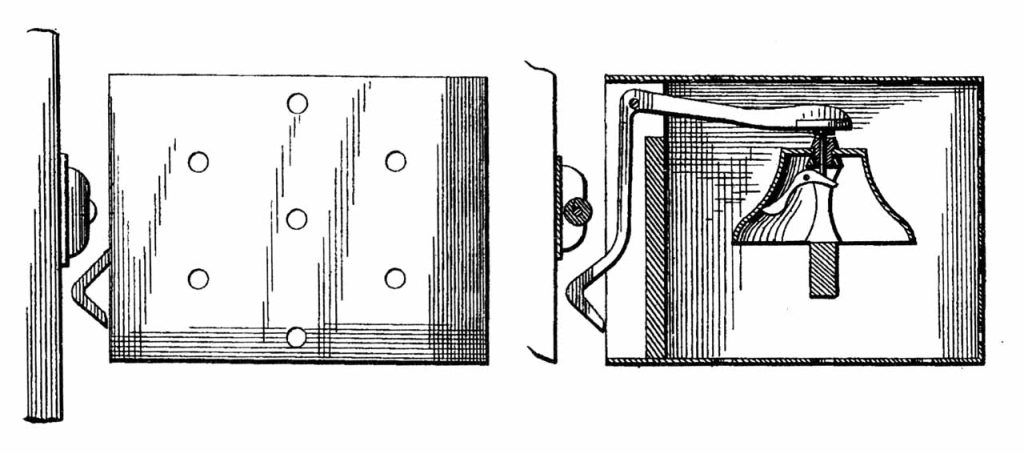

In 1885, Louis W. Pedicord patented an alarm that also rang a bell at each floor.[3] His alarm was mounted on top of the elevator car (Figure 2). Pedicord also noted that his device could be used to signal when the car doors were opening. The following year, John W. Metz patented a similar device that was specifically intended to notify the operator of the car’s position relative to each floor.[4] The design employed a bell mounted under the car that was activated by a rack attached to the shaft and which extended below and just above the floor level (Figure 3). When the car approached a floor, the bell would begin to ring and, when the car was level with the floor, it would stop; it would also ring when the car departed. Thus:

“The person running the elevator is automatically notified every time the floor of the building is reached, and persons desiring to ride up and down are also notified that the car is just arriving at or departing from the floor.”[4]

In 1887, Charles E. Chinnock patented one of the first electro-magnetic alarm systems.[5] Chinnock (1845-1915) was an electrical engineer described as “a pioneer in the electric light and telephone fields.”[6] His system, powered by batteries, was designed to ring an alarm bell if the car did not stop level with the floor and if the car attempted to depart while the doors were open:

“Many accidents occur in elevators by reason of the omission of the attendants to properly close the doors controlling access from the several floors of the buildings … and accidents also frequently happen through the failure of the attendants to stop the elevators in the right positions with relation to the doors.”[5]

The alarm would also sound if someone attempted to open a door when a car was not at a landing. In his patent, Chinnock noted that: “The electro-magnetic bells are … arranged to give an alarm to some special person in the building — as, for instance, the janitor. An electro-magnetic bell can also be arranged to sound an alarm in the elevator.” His apparent ambivalence on the alarm’s placement and its intended audience is somewhat surprising, given that a signal indicating a level stop and closed doors would appear to be information most needed by the operator.

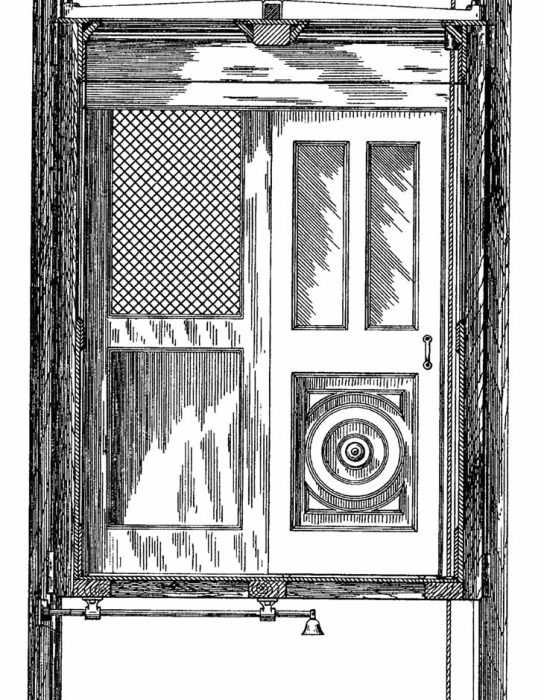

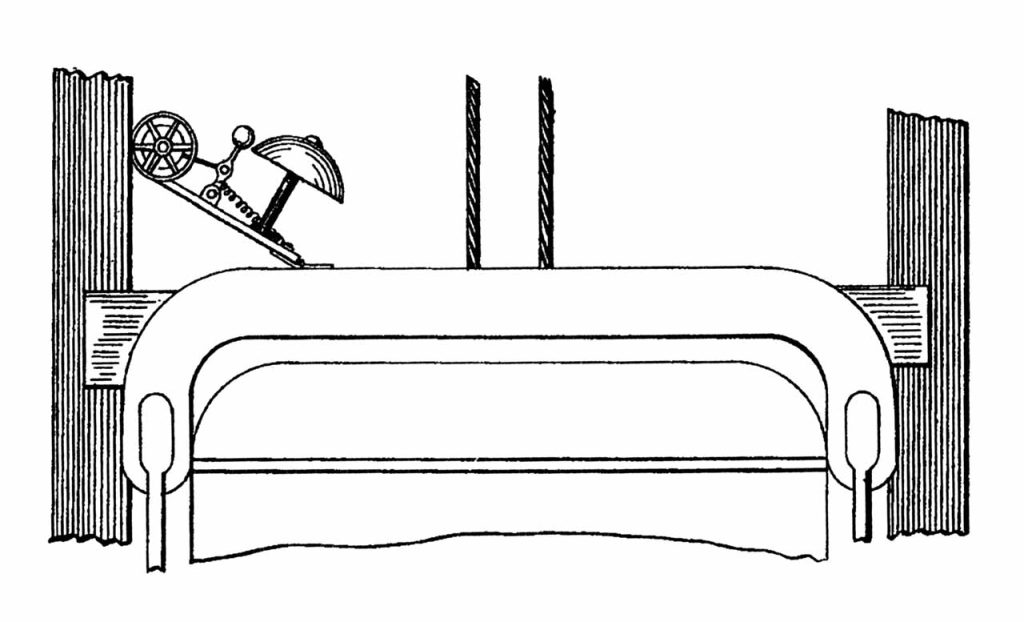

The next two patents were variations on earlier schemes and concerned designs that rang a bell as a car arrived at or departed from a floor. John H. Flaugher and Alvin B. Scott’s 1887 patent employed a bell located under the car that rang as it passed over a combination cam/roller device (Figure 4).[7] While the idea was not original, the inventors included a reference to a unique extension of their system: They suggested that additional cams per floor could be added such that the number of bell rings would equal the floor’s number and thus would announce the car’s location. Arthur Oakley’s 1888 patent did not include a similar innovative idea, and, in fact, he stated that: “I am aware that no single feature of my invention is novel. I am also aware that combinations of such devices having the same general purpose as mine have been proposed and described in prior publications.”[8] The rationale for his design was that its “construction is simpler than any heretofore known and (is) quite efficient.”[8]

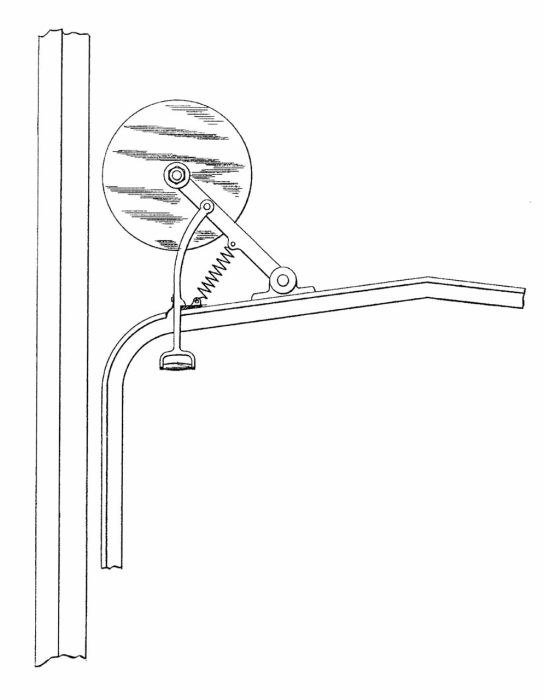

Two additional patents from 1888 carried out the concept of a ringing alarm bell to notify passengers of the car’s passage through the shaft to its, perhaps, logical extreme. John W. Holdsworth and John Einig designed systems that caused the alarm bell to ring continuously as the car traveled up and down the shaft.[9,10] Holdsworth placed a large bell on top of the car, which was connected to a traveling wheel that ran along the side of the shaft (Figure 5). Einig employed a similar system; however, he used a small bell located under the car (Figure 6). It may be safe to assume that, whether it would have been the continuous loud ringing of Holdsworth’s bell or the gentle tinkling sound of Einig’s bell, riders, waiting passengers and building occupants would have quickly grown tired of the constant sound of the elevator alarm.

While all of the patents examined thus far included the inventor’s rationale for their design, the patent text did not provide insight into the precise motivation or inspiration that prompted the inventor to design an elevator alarm. This was not the case with Alfred L. Brice and his patent for an Alarm for Elevators:

“In modern buildings of any considerable height, passenger or freight elevators are in practically constant operation during the business hours of the day and are employed as a means of entrance to and egress from the upper stories of the structure. In these large buildings, the danger from fire is most to be feared, and it becomes important to warn all the occupants in case fire should be discovered, in order that they may have the opportunity to escape … My invention relates to alarms for elevators, and has for its object the utilization of the elevator as a means for warning the occupants of a building in case of fire or other imminent danger.”[11]

The impetus for Brice’s design was a disastrous fire that had occurred in the Minneapolis Tribune Building on the evening of November 30, 1889. The building was almost totally destroyed, and several lives were lost. One of the fire’s “heroes” was elevator operator Charles A. Smith, who was the first person to realize that the building was on fire. After he discovered the fire on the third floor, he immediately went to the seventh or top floor and warned the occupants about the danger. He then began carrying people to safety, stopping only after the fire engulfed the elevator shaft. While he was credited with saving more than 20 people, it was recognized that it took far too long for the warning to be issued throughout the building.

The story of the heroic elevator operator received extensive press coverage, and it’s likely this inspired Brice, a Minneapolis attorney, to pursue his patent, the application of which was filed on December 23, 1889. He utilized an idea found in earlier alarm patents — the continuously ringing bell — as the basis for his design, in which he proposed to “mount on the elevator-car, preferably on the roof thereof, a gong or bell of resounding capacity sufficient to cause the alarm to be heard all over the building.”[11] The bell was actually a series of hammers or clappers enclosed in a metal case that, when rotated, would produce a rapid series of loud ringing sounds. The bell was mounted such that under normal operating conditions it made no sound. If the elevator operator became aware of or was notified that there was a fire in the building, he would pull down on a lever in the car, “thereby engaging the friction wheel or pulley with the guideway of the elevator-shaft. As the elevator moves up and down, said wheel is therefore rotated on the arbor, and the cams successively engage with and trip the bell hammer or clapper and cause the alarm to be sounded” (Figure 7).[11] The continuous ringing of the bell would also let building occupants know that the elevator was in operation and available as a means of escape. Brice’s patent was awarded on April 22, 1890. Two months later, a letter to the editor appeared in the Minneapolis Star Tribune in which the author claimed:

“Had (Brice’s) elevator alarm been in existence and in use in the Tribune Building at the time of the fire, I believe no lives would have [been] lost, as the poor fellows who perished would have been warned of their danger long before the flames had made such great headway.”[12]

This brief survey of the origin of elevator alarms in the 19th century revealed concerns about safety with regard to the movement of the elevator car, leveling of the car and controlling the car (and shaft) doors. It also served as a reminder that, during this period, the elevator was also viewed as an important means of escape in the event of a building fire. The latter topic will be the subject of a future article, which will examine the role elevators played in evacuating buildings. Lastly, another future article will investigate the emergence in the early 20th century of elevator alarms whose function matches the current definition — devices that allow a “trapped” passenger to signal (or call) for help.

References

[1] Benjamin Howard, Improvement in Alarms and Indicators for Elevators, 150,321 (April 28, 1874).

[2] Amos Nickerson, Alarm for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 284,654 (September 11, 1883).

[3] Louis W. Pedicord, Elevator Alarm Bell, U.S. Patent No. 318,202 (May 19, 1885).

[4] John W. Metz, Bell Alarm for Elevator Cars, U.S. Patent No. 350,146 (October 5, 1886).

[5] Charles E. Chinnock, Electric Alarm, U.S. Patent No. 355,384 (January 4, 1887).

[6] “Obituary,” Engineering News (June 17, 1915).

[7] John Henry Flaugher (1853-1912) & Alvin Brooks Scott (1853-1933), Automatic Bell Alarm for Elevator Cages, U.S. Patent No. 356,461 (January 25, 1887).

[8] Arthur Oakley, Elevator Alarm, U.S. Patent No. 377,403 (February 7, 1888).

[9] John W. Holdsworth, Alarm for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 381,015 (April 10, 1888).

[10] John Einig, Elevator Alarm, U.S. Patent No. 384,831 (June 6, 1888).

[11] Alfred L. Brice, Alarm for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 426,104 (April 22, 1890).

[12] F. Fremont Reed, “An Elevator Alarm Bell,” Minneapolis Star Tribune (June 28, 1890).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.