Elevator Maintenance – the Past, the Present, the Future

Jun 2, 2023

by TAK Mathews

This paper was presented at the 2022 International Elevator & Escalator Symposium in Barcelona, Spain.

This paper was presented at the 2022 International Elevator & Escalator Symposium in Barcelona, Spain.

Abstract

Since Elisha Graves Otis’ “All Safe Gentlemen” declaration of 1853, elevator technology, standards and practices have evolved greatly. The dependency on elevators has also grown such that there is no person on the face of the earth who is not directly or indirectly dependent on elevators.

Robust standards, design and testing, component manufacture and elevator installation sets the foundation for equipment reliability and safety. However, it is subsequent maintenance that ensures the sustainability of equipment life and reliability and user safety. This paper will trace how elevator maintenance trends have changed over the last decades and explore whether the trends are progressive or regressive. This paper will also attempt to predict future trends and their impact on reliability and safety.

1. Introduction

While Elisha Graves Otis set the foundation for the elevator industry with his invention and his “All Safe Gentlemen” declaration, elevator and escalator safety can be achieved only through a systematic and non-compromising approach through the three distinct phases (Figure 1) of the life cycle of Design, Execution and Maintenance.

Design Phase

Building Design and Elevatoring: The impact of inadequate elevatoring on the safety of the equipment is mostly overlooked. When the building lacks an adequate number of elevators or escalators, overuse of the equipment beyond the design intent is unavoidable. While most equipment over the last two centuries was designed generally for 240 starts per hour and a design life of 25 years, it is not uncommon to find that neo elevators are designed for 120 starts per hour or less and a design life of less than 15 years. Another outcome of inadequate elevatoring is limited equipment shutdown time available for maintenance.

Equipment and Component Design: This part of the design has garnered significant focus with many safety standards and codes having been established around the world. As per Gray,[4] as early as 1878 a draft ordinance was presented to the Chicago City Council. Worldwide, these standards and codes have evolved with time deriving from decades of experience. Whether the current trend is always toward ensuring safety is a topic for another debate.

Execution Phase

Even the best-designed equipment is only about as good as the quality of its installation. Any aspect of poor manufacture or installation, if it can ever be remedied, works out to be very expensive. There have been instances when some of the remedies have cost companies millions of dollars. Rarely can any level of good maintenance compensate for bad design or execution.

Maintenance Phase

The importance of the Maintenance phase is summed up by various experts. McCain states, “The safety of elevator equipment is dependent on its proper maintenance and use.”[7] Montesano declares, “A systematic maintenance program is essential if the equipment is to continue to perform at peak efficiency.”[8] Bialy states, “Maintenance and inspection are required to ensure that the design aspects upon which reliable, safe operation depends are, in reality, effective.”[3]

Various experts have been addressing their opinions on approach to maintenance and trends. Koshak’s “Method for Managing Maintenance”[5] and “A Discussion About Preventive-Maintenance Practices”[6] and Akçay’s “Maintenance, the Correct Approach to Raise the Quality”[1] are examples. About a decade back, at its annual forum, International Association of Elevator Consultants (IAEC) had multiple groups discussing maintenance trends. For reasons of possible litigation threats that were not fully clear to the author, the findings and opinions of these groups with combined experience of more than 1,000 years were not published.

This paper will study the trends during the critical maintenance phase of elevators and escalators.

2. Maintenance Approach Until the 1980s

This author joined a global elevator major in the 1980s. At the company, maintenance was called EXAMINATION, and the maintenance mechanic was called an EXAMINER. The time allocated for the maintenance of a unit was referred to as EXAMINATION HOURS. The idea was that maintenance principally involved examination of the equipment, component-wise, and attending to this required rectification. The national head for service of the company would stress that examination required the application of all senses and experience. Obviously, a high degree of expertise and experience was required.

ASME 17.1 2019 defines “maintenance: a process of routine examination, lubrication, cleaning, and adjustment of parts, components, and/or subsystems for the purpose of ensuring performance is in accordance with the applicable Code requirements.”[2] Maintenance activities listed by EN 13015 includes checks as a main activity in addition to lubrication, rescue operation, adjustment, repair and replacement of worn-out components. Through his Elevator Maintenance Manual,[7] McCain’s emphasis is on Examine, Check or Inspection, which indicates that this maintenance principle was not limited to just the author’s first employer.

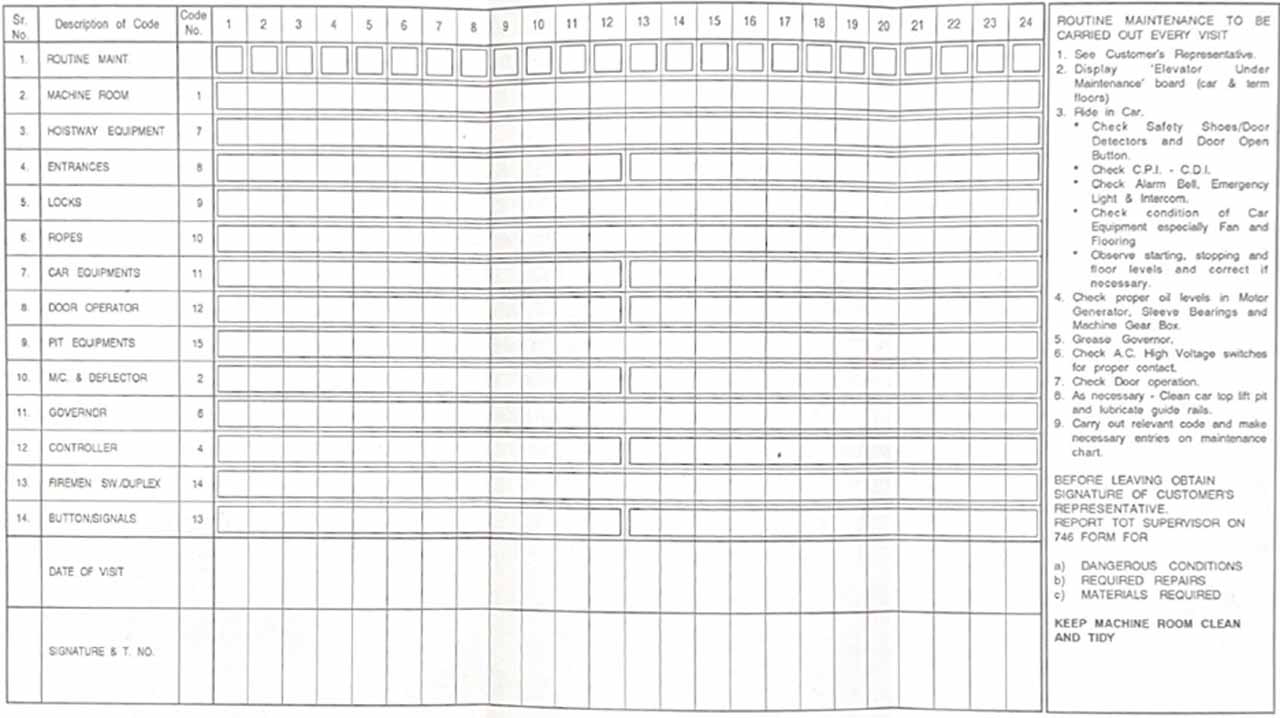

At the author’s employer of the 1980s, examination was a twice-a-month affair (Figure 2) by a two-member team consisting of the Examiner and his helper (most often a trainee). In addition to the carrying out of examination and required rectification, the mentor and trainee arrangement ensured that there was a steady stream of well-trained and mentored trainees ready to become Examiners with independent routes.

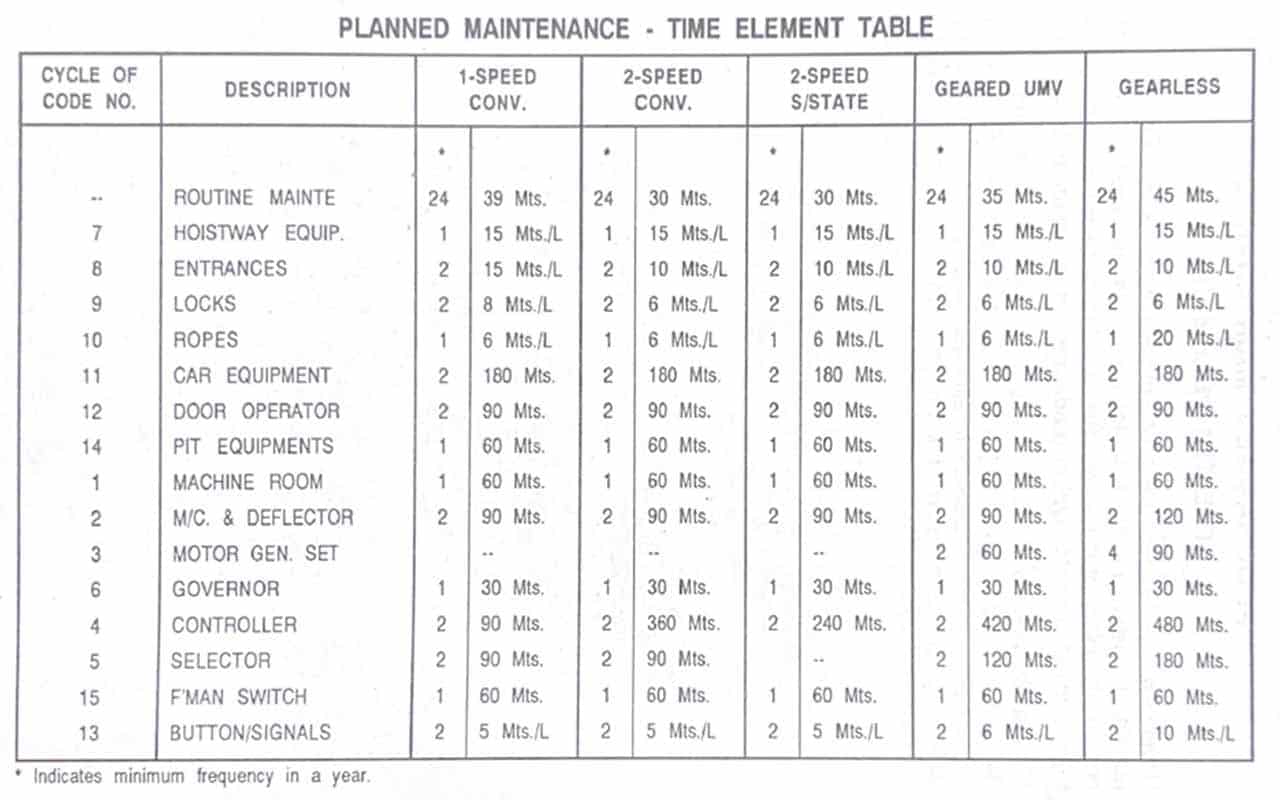

The route allocation/loading was based on an estimate of the hours required for examination, with an additional allowance for breakdowns, travel, education, toolbox talks, meetings, administration activities, vacations/holidays, time loss, etc. The estimate was derived from decades of experience and time studies (Figure 3).

Depending on the type of equipment, number of stops, usage patterns and geographical spread, the number of units would vary between 50 to 70 units. Koshak[6] estimates that typically 70 to 90 units would be assigned to a route mechanic.

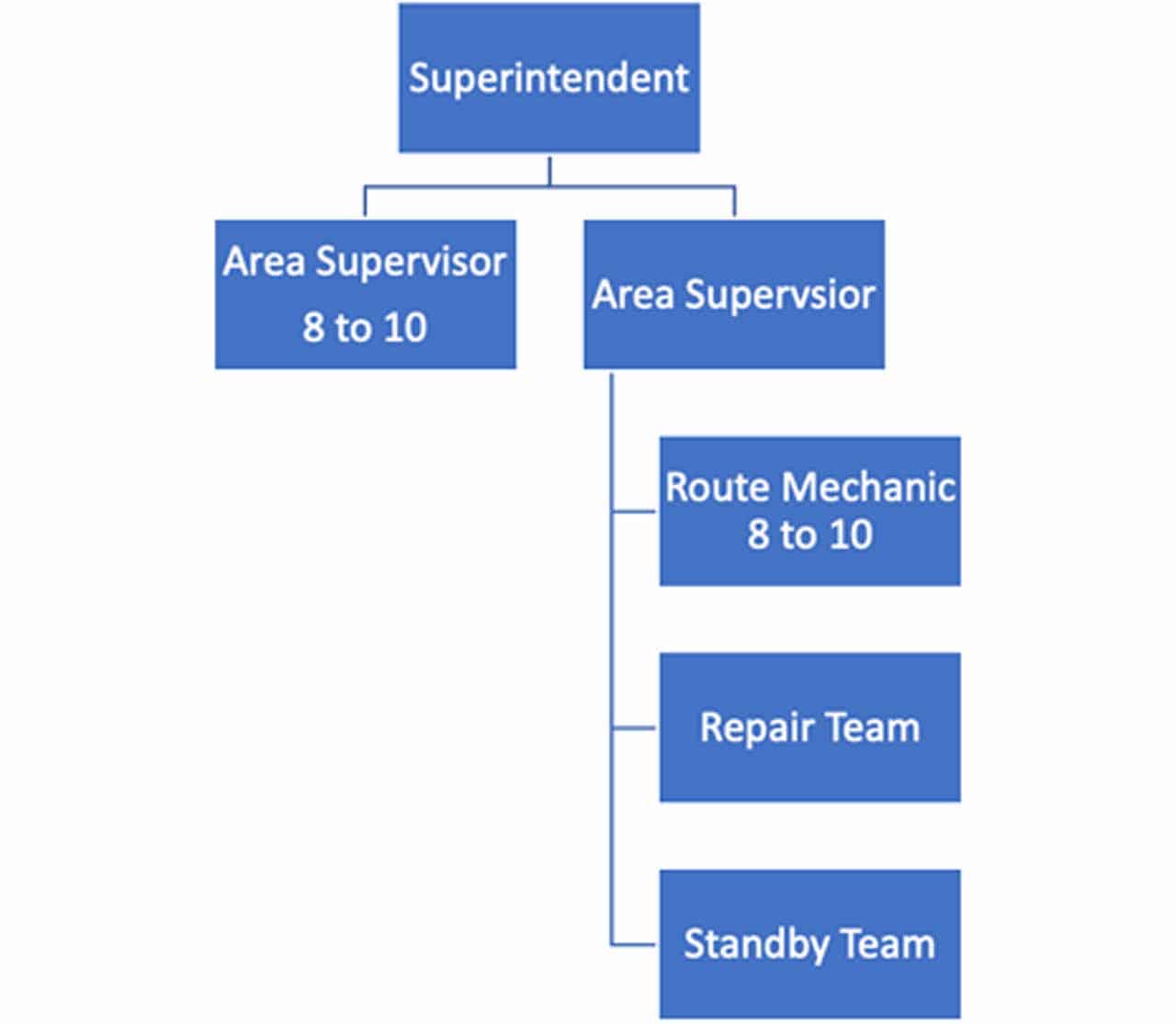

The primary responsibility of the area supervisor was to carry out the annual equipment survey of all the units in his/her area, which effectively established the number of routes a single area supervisor could supervise (Figure 4). The survey report would detail the quality of maintenance, backlog of work, including repair requirements, as well as modernization recommendations. It would also throw up information for the annual performance appraisal route examiners and helpers and training requirements.

A major company introduces their maintenance manual with the following words of wisdom, “THE MAIN RESPONSIBILITY OF THE MAINTENANCE DEPARTMENT IS THE SERVICE WE GIVE TO OUR CUSTOMERS. WITHOUT THAT CUSTOMER, THERE IS NO REASON FOR OUR EXISTENCE. ALL OUR EFFORTS DEVOTED TO MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR OF LIFTS AND ESCALATORS ARE DIRECTED TO ONE COMMON TARGET: TO KEEP THE EQUIPMENT IN A CLEAN, SAFE AND OPTIMAL OPERATING CONDITION.” Koshak[6] states, “In the 1980s, elevator companies competed on service, quality and performance.”

While the profitability and bottom-line was a priority, the primary emphasis was on quality of service and equipment up time.

3. Maintenance Approach – the Changing 1990s and to Now

Toward the end of the 1980s (earlier in some other countries), the approach to maintenance started changing. The emphasis shifted toward profitability. Within a few years of the release of the manual referred to in the previous chapter, maintenance took on a drastic change and was discarded.

The first casualty was the twice-a-month maintenance frequency, which was reduced to once a month. While twice a month could be considered excessive, once a month was the absolute minimum. The next change was the two-member teams being reduced to one-man “teams.” While this, too, could be justified for a number of maintenance activities, an unintended long-term consequence is the reduction in the average competency levels among the next generation of mechanics.

The changes did not stop with these profit-enhancing initiatives. The route loading started increasing to an extent that examination or checks became an impossibility. Often, route mechanics could visit the equipment only if there was a breakdown — a common joke is that facility managers would create breakdowns to catch the route mechanic’s attention. Maintenance supervision became a paper and reporting exercise rather than actual supervision of work and inspection of the installations. Maintenance supervisors became more like data analysts. This, in turn, reduced the need for maintenance supervisors to be technically competent or experienced, a skill not necessary for analyzing and presenting statistics.

An argument often put forth is that modern-day elevators consist of maintenance-free components. This is stressed even more often for the current day machine-room-less elevators where examination and inspection of operational equipment like machines and governors is impossible. On the contrary, the modern-day microprocessor controllers with self-diagnostics and reset options make attending breakdowns easy without the need for in-depth technical knowledge or root cause analysis, which adds to the problem.

Richard Blaska’s opinion, “The claim that we all have heard that these new systems require little or no maintenance is almost laughable,” sums up the reality.

4. Maintenance Trends Opinion Survey

Surveys were circulated to understand perceptions as well as trends. The data collection was through various social media platforms and groups. The round-the-clock data entry timelines would tend to indicate that respondents were from around the globe.

It is recognized that the sample size is not large enough to provide a definitive conclusion. The trends should, however, be considered as a direction that requires further detailed study and candid investigation by various industry associations and industry publications.

4.1 Maintenance Trends

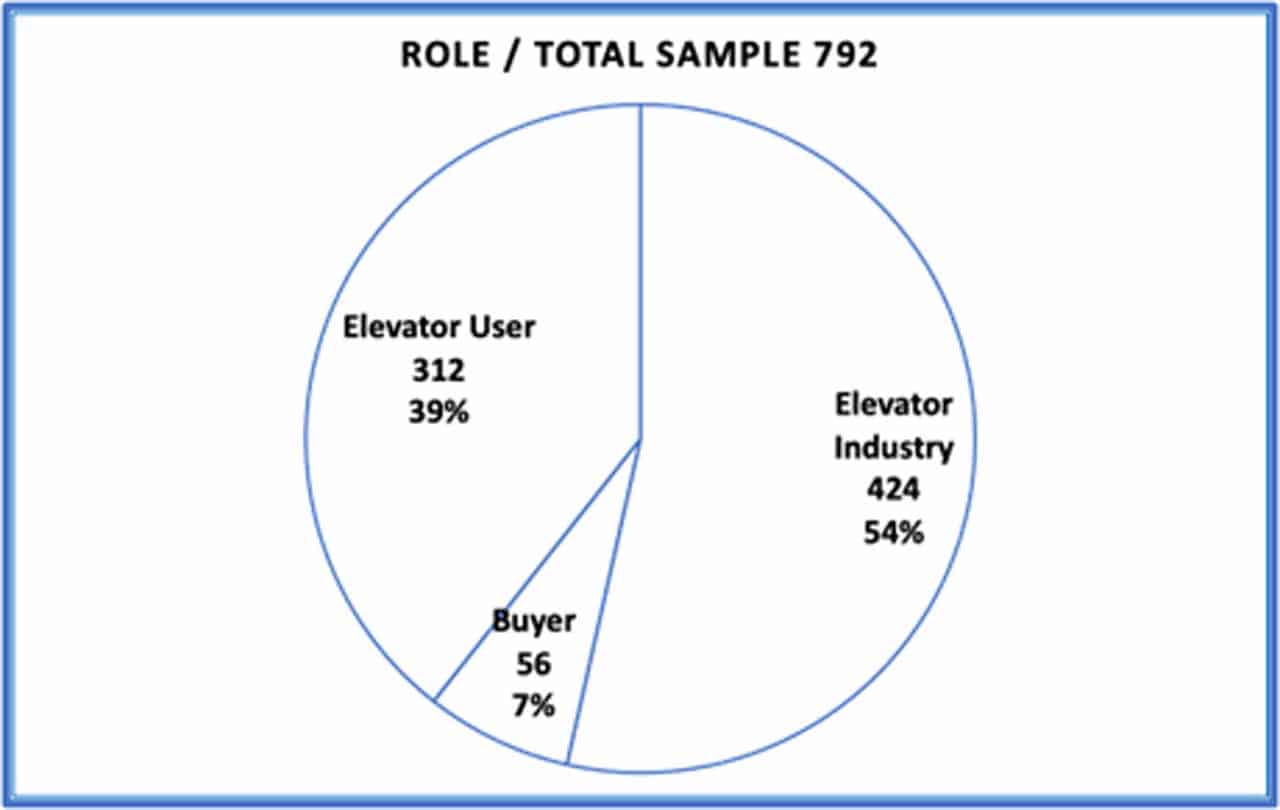

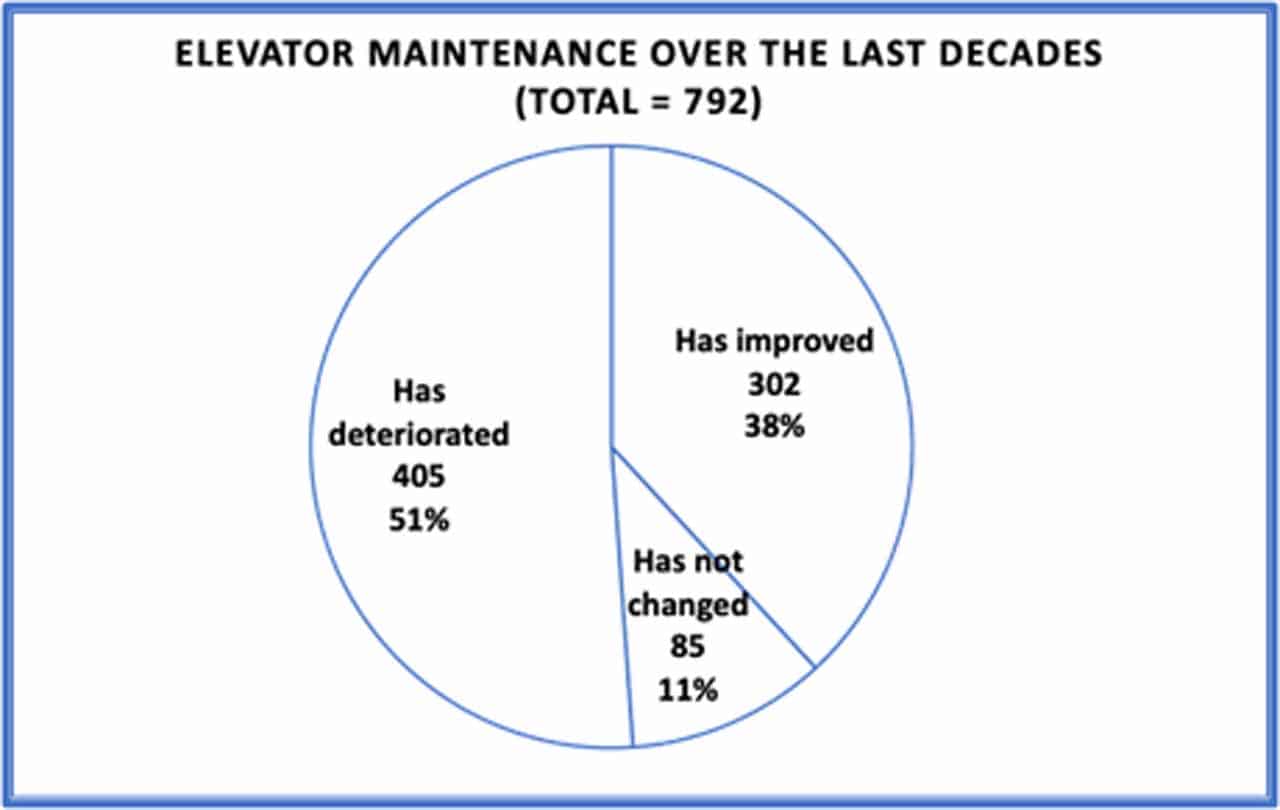

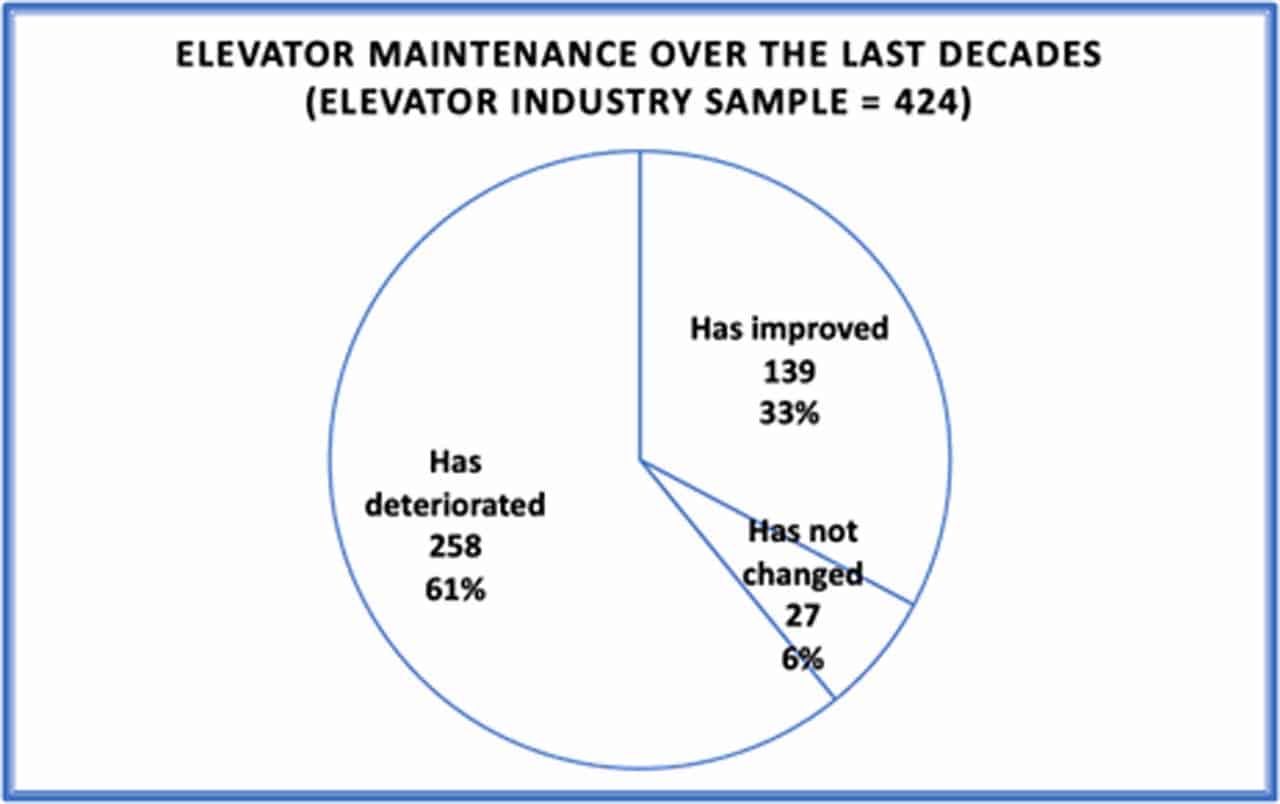

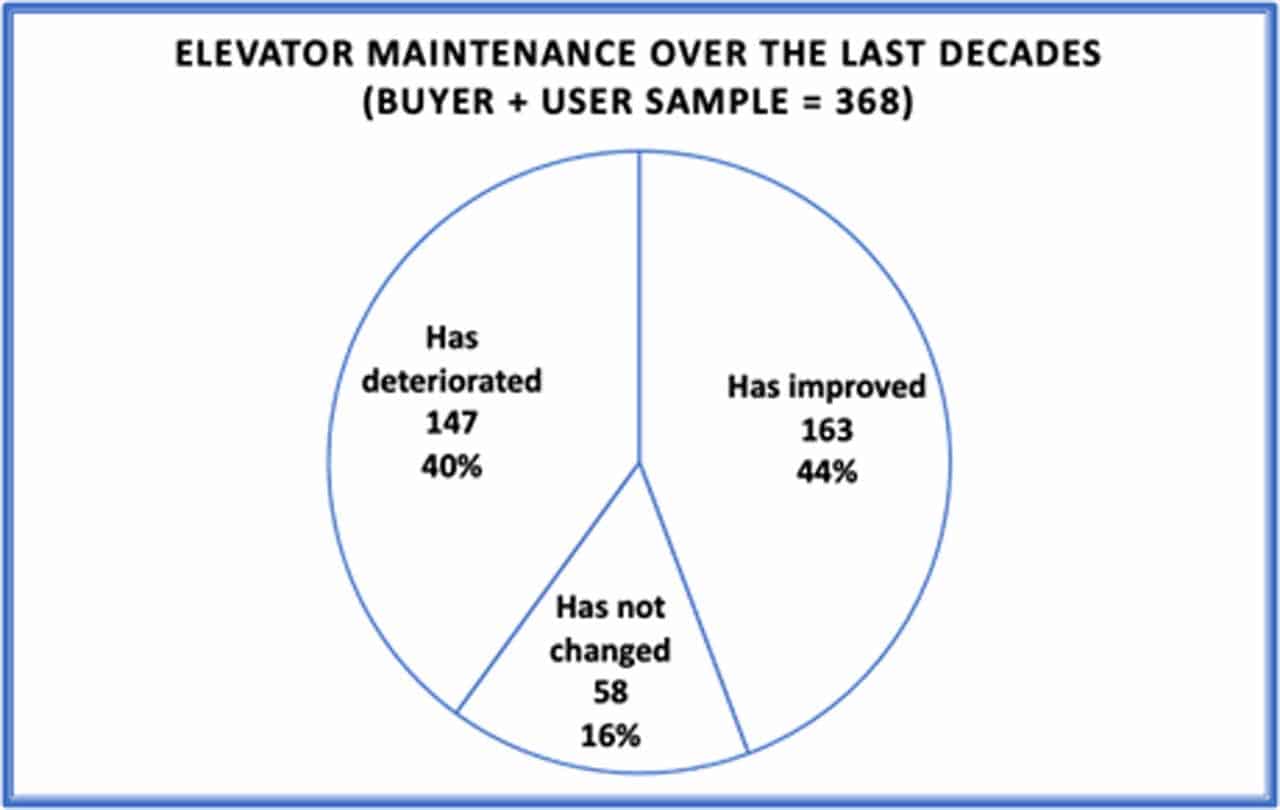

Seven hundred and ninety-two (Figure 5) responded to the two-question survey, of which 51% (Figure 6) opined that maintenance has deteriorated. While 62% (Figure 7) from the elevator industry opined that maintenance has deteriorated, 44% of users, and buyers (Figure 8) opined that maintenance had improved.

4.2 Maintenance Practices

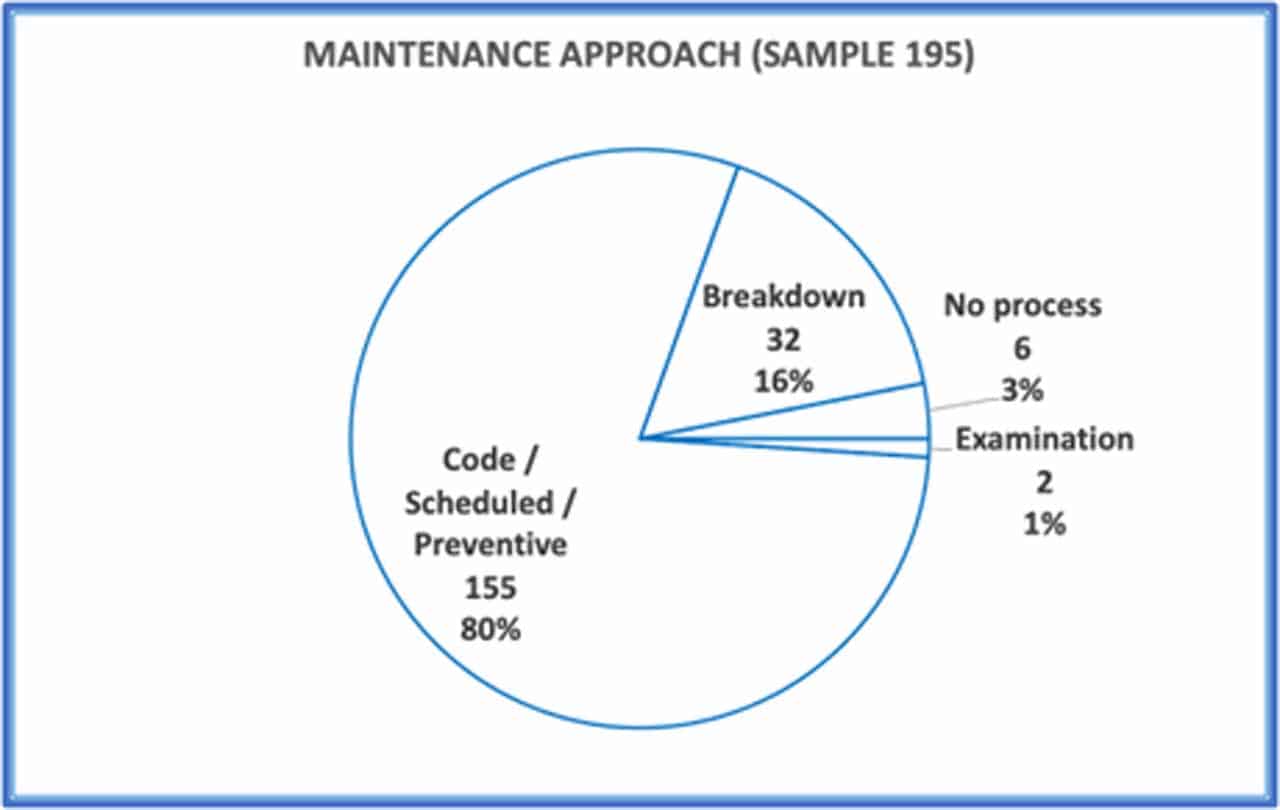

Of the 195 respondents from the elevator industry, 80% (Figure 9) opined that their company followed a Code/Scheduled/Preventive maintenance program. At 1%, it is clear that the traditional examination has become rare.

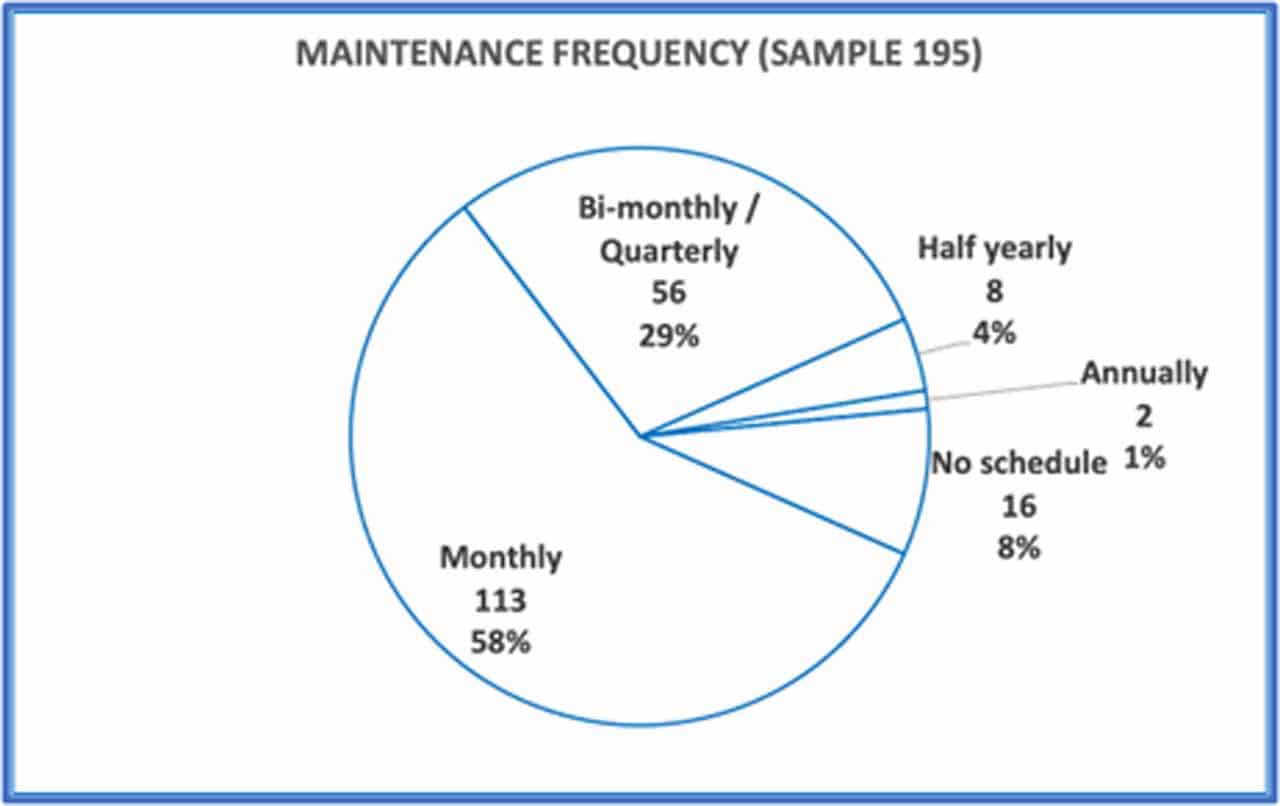

More than half (Figure 10) opined that their company followed a monthly servicing frequency. It is worrisome that 8% opined that their company did not have a schedule.

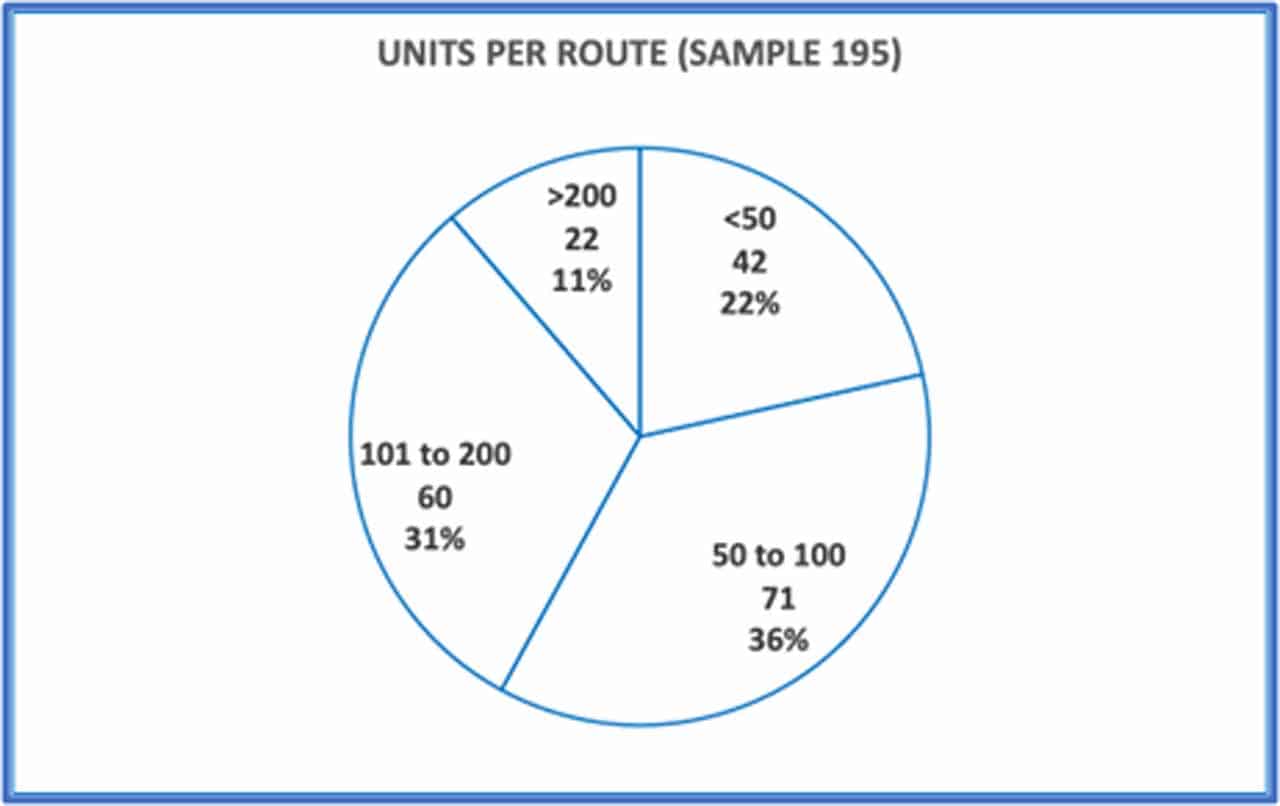

Thirty-six percent (Figure 11) opined that, at their company, the average number of units per route were between 50 to 100, while 31% opined that the number of units would be between 101 to 200. The point to note is that 11% were with more than 200 units per route. Per Koshak, “In the late 1980s, these numbers grew to 150 to 300 units per route, which is what we see today.”[6] He goes on to state, “Some major company mechanics tell me that they have up to 350 units on their route.”[6]

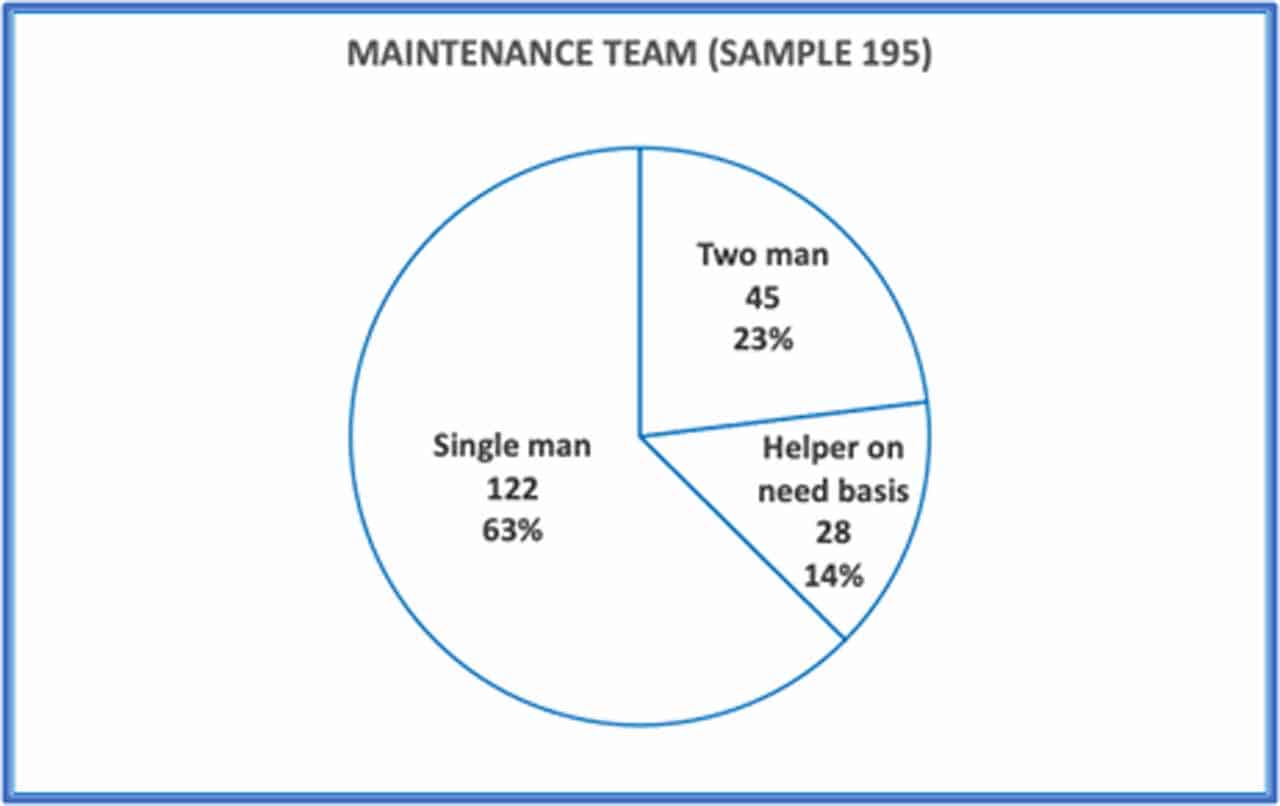

Maintenance teams are now predominantly single man “teams” (Figure 12).

5. Remote Maintenance and IoT

Remote monitoring of elevators took roots in the 1980s. The original thoughts behind remote monitoring and maintenance were to provide proactive alerts to mechanics, thereby reducing breakdowns and entrapments.

Suzuki et. al. [9] states, “In the early 1980s, Mitsubishi Elevators began a remote-monitoring service, which was an automatic alert service of problems or entrapment of elevator passengers … and a maintenance engineer is dispatched to the site.” The paper goes on to state, “Continuous inspection function is utilized to improve the quality of maintenance and operational availability of elevators.” Through the paper, the emphasis is clear that remote monitoring is considered as a tool to increase reliability and improve response times.

Over the last decade or so, Internet of Things (IoT) has become the buzzword. The elevator industry, too, has seen trends with even creation of special IoT departments. FutureIoT states, “Over the last decade, advances in AI and IoT have changed elevators and escalators beyond their mechanical function of getting people to travel up high rises with speed and comfort.”[12] Transparency Market Research reports, “The global IoT in elevators market is expected to cross ~US$63.5 billion by 2030 from ~US$14 billion in 2020.”[15]

It is the author’s contention that remote monitoring and IoT are much-required advancements for providing safer and more reliable elevator and escalator maintenance. However, the problem is that these much-needed advancements are now being expected to substitute for physical maintenance rather than augment the maintenance activities. These advancements have been hijacked as a means to increase profitability through reduction in physical maintenance, and thereby a reduction in labor costs. It also has become a justification to de-skill the maintenance mechanic and supervisors.

The author has attended a few presentations by IoT experts and vendors who claim that not only will the additional costs of implementing IoT for maintenance be offset through manpower reduction, but this would actually increase profitability.

Market Insider reports “Elevator leverages IoT to upgrade service solutions … The improvement in the management of data has vastly facilitated the remote inspection and maintenance of elevators, as well as the real-time capture of fault information, reducing the amount of manpower needed for elevator management by some 70%.”[13] Hasenstab states, “also comes with 24/7 monitoring, it can reduce the number of regular visits.”[11]

The question that begs to be answered is how many more units will be loaded on to a maintenance mechanic who already has 200 to 300[6] units on his route?

6. Reality of Maintenance Sans Examination

The author’s company is involved in the audit of elevators and escalators. The deterioration in physical maintenance is widespread. Figures 13 and 14 are of elevators that were under comprehensive maintenance contracts. The four elevators had fewer than six breakdowns over a span of over two years. At 0.75 calls per unit per annum, not surprisingly, most condominium owners were extremely happy with the maintenance company.

When confronted with the state of the ropes, the maintenance company’s initial response was that the very low callback rate was proof that the maintenance quality was top notch. The supervisor with more than 1,000 units under him had never been to this building.

In many ways this, as well as other similar experiences, are indications of what to expect when remote monitoring and IoT becomes substitutes for physical examination and maintenance.

7. Maintenance Practices — Aircraft

Aircraft are possibly the means of transport that are the most remotely monitored. IoT applications are assisting in aircraft maintenance by collecting data to provide advance alerts to maintenance engineers, thereby enhancing safety. However, these advancements do not intend to reduce the required inspections and maintenance programs or regular maintenance, as is being suggested for elevators and escalators. In fact, even after all the activities by all the maintenance experts and input from all sensors and gauges, the pilot (or co-pilot) will still do a walk-around of the aircraft before take-off. “No aircraft is so tolerant of neglect that it is safe in the absence of an effective inspection and maintenance program.”[14]

Despite the level of remote monitoring, it is pertinent to note that the disappearance of MH 370 remains a mystery even after eight years. The Federal Aviation Administration’s report on the Boeing 737 Max states crashes have been linked to erroneous data from sensors.[10]

At a panel discussion held a few years back, the author asked the audience whether they would be comfortable flying back home on aircraft that they knew was maintained purely based on remote monitoring and IoT. The silence was deafening.

Two other points that the elevator industry should adopt immediately from practices by the airline industry:

Throughout the life of an aircraft, manufacturing defects, changes in service or design improvements often occur. The original manufacturer distributes the information to the owner/operator of the aircraft.

Every incident is investigated and reported publicly to ensure prevention and repeat of such incidents.

Both these activities, which are alien to the elevator industry, are also followed by the National Highway Transport Safety Association.

8. The Future of Elevator Maintenance and Conclusion

Market Insider reports, “China’s state Administration for Market regulation issued a document in April of this year, encouraging all stakeholders in the elevator industry chain to embrace service models that comply with the need for on-demand maintenance.”[13] Considering that many from the modern-day elevator industry who have very little hands-on experience are champions of such thoughts, it is feared that elevator maintenance will soon be relegated to purely a need-based activity.

The writing on the wall is clear. It is no longer necessarily “All Safe Gentlemen.”

References

[1] Akçay, Erol (2019) “Elevator Maintenance and Inspection: Recommendations, Regulations and Codes 1880 – 1940” International Elevator and Escalator Symposium 2018, Elevator World.

[2] ASME A17.1 – 2019 Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators, The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, USA.

[3] Bialy, Louis (2019) “The Role of Maintenance and Inspection in Risk Reduction,” International Elevator and Escalator Symposium 2019, Elevator World.

[4] Gray, Lee E. Dr. (2019) “Maintenance, the Correct Approach to Raise the Quality,” International Elevator and Escalator Symposium 2019, Elevator World.

[5] Koshak, John (2018) “Method for Managing Maintenance,” International Elevator and Escalator Symposium 2018, Elevator World.

[6] Koshak, John (2022) “A Discussion About Preventive-Maintenance Practices,” Elevator World September 2022.

[7] McCain, Zack (2005) Elevator Maintenance Manual, Elevator WorldInc., Mobile, Alabama, USA

[8] Montesano, Nicholas J (2010) “The Vertical Transportation Handbook,” 4th Edition, Elevator World.

[9] Suzuki, Naohiko et.al. (2019) “Remote Maintenance Service of Mitsubishi Elevators,” International Elevator and Escalator Symposium 2019, Elevator World

[10] Federal Aviation Administration (2020) “Summary of the FAA’s Review of the Boeing 737 MAX”

[11] elevatorworld.com/article/how-to-maximize-the-value-of-maintenance-and-service-contracts-using-the-internet-of-things/

[12] futureiot.tech/ai-and-iot-are-the-keys-to-smarter-lifts-and-escalators/

[13] markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/hitachi-elevator-leverages-iot-to-upgrade-service-solutions-targeting-china-s-7-3-million-elevators-currently-in-operation-1029667235

[14] skybrary.aero/articles/aircraft-maintenance

[15] transparencymarketresearch.com/iot-in-elevators-market.html

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.