Elevators’ Horizontal Cousins Packed with Potential

Oct 1, 2013

Automated people movers are an untapped resource in the growth and planning of tomorrow’s cities.

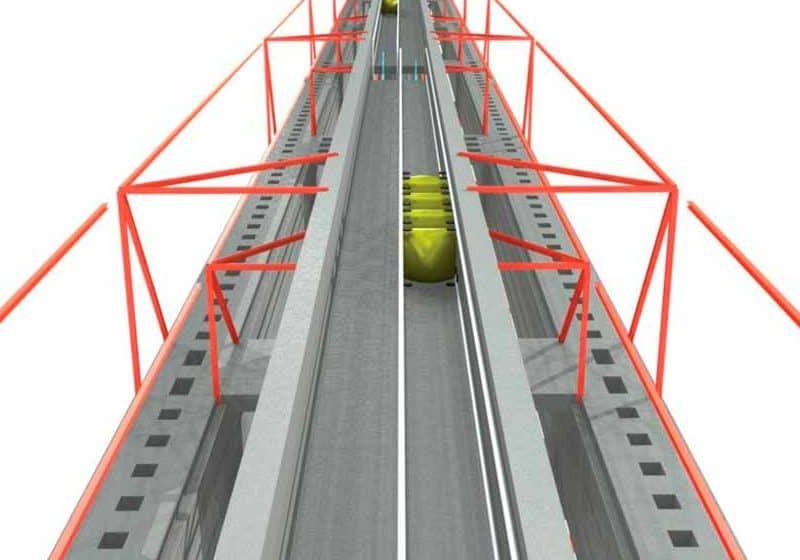

In the future, many large elevator lobbies will be designed for easy interface with horizontal movement systems. Automated people movers (APMs) are commonly known as people movers, shuttles, monorails and trams. A step up from moving walks, APMs are driverless horizontal passenger mobility systems. Like their vertical cousins, their performance and sophistication levels vary.

Some APMs are simple back-and-forth shuttles akin to an elevator between only two floors. More elaborate APMs serve a string of stations. High-end APMs are known as personal rapid transit (PRT), with taxi-sized vehicles and ramps that bring them off the main guideway (track) when they make a station stop, which can be adjacent to or even integrated within a civil building, such as an office tower, apartment complex, hospital or other large urban facility. (The term “PRT” is roughly equivalent to “podcar” and “automated transit network.”). The building’s elevators should be nearby, and the space between should be a place for interactions. These multimodal lobbies will have several mobility elements to interface with the APM – elevators, pedestrian circulation, stairways, and perhaps escalators and moving walks. APM stations are commonly found at large airports and hint at what lies in store for elevator professionals around the world.

Ultimately, to be managed as active public spaces, intermodal lobbies need careful design attention. If PRT is the horizontal mode, the off-line ramp can be located with great flexibility inside the building or against an exterior wall. Designers of multimodal lobbies will need to analyze and coordinate a wide range of dimensions and requirements. APM dimensions are considerably smaller for buses and rail transit. PRT guideway and station dimensions are even smaller. Moreover, for PRT systems, the area for boarding and de-boarding passengers is off the main guideway.

A multimodal lobby is unlikely to be at ground level. A building’s main entrance(s) are, by definition, at ground level and convenient to sidewalks and streets. Of course, larger buildings – especially those on hills – can have several principal entries. However, APM engineers, seeking to avoid conflicting traffic, need to provide an exclusive (or well-protected) right-of-way. Thus, APM guideways are not generally placed at ground level. Because underground infrastructure is costly, APMs are typically envisioned and promoted as elevated infrastructure. As a result, stations are likely to be located at second- or third-floor levels. Basement-level alternatives are possible but expensive.

Securing District Benefits

Even some informed architects and engineers have not explored the many benefits of introducing APM guideways into a master plan. APMs can move not only passengers, but parcels, supplies and small cargo. On a district level, APMs can create easy and economic conduits for wires, cables, pneumatic tubes and heating/cooling fluids. If heating and cooling are included, APMs can also solve winter icing problems during frigid winters. Besides moving passengers, APM networks can transport parcels, supplies and small cargo.

So why aren’t there more examples of multimodal lobbies, other than in a few dozen airports and large passenger terminals? Some point to high APM costs, while APM suppliers and consultants report that airports demand highly reliable service, often 24/7. Others blame architects’ and public safety officials’ lack of creativity and unfamiliarity with the many district benefits APMs can bring. Zoning and district management bureaucracies are inertial, but innovative district designs need flexibility and governmental support.

Public safety demands that lines of responsibility and command be unambiguous and explicit. Elevators, escalators and moving walks (hereafter referred to as “elevators”) are governed by well-debated rules and regulations. Signatures with legal authority must be in place before an installation opens to the public. Routine inspections are mandatory. Reporting procedures are reviewed.

APMs are less commonly known to the disciplined worlds of building/

elevator inspections and insurance reviews. Will APMs and their stations in intermodal lobbies fall under the same regulatory offices as elevators? Or, do they belong under rail authorities? The picture in the U.S. varies by state.

Who will have to worry about the cleanliness and security of multimodal lobby areas? Most likely, it will be someone within a specialized facility-management unit.

High Up or Over?

The 220-story Sky City is being built in Changsha, China (ELEVATOR WORLD, February and August 2013). It is largely ego that drives the decision to build such higher-than-thou structures. Economic and safety issues would lead more rational developers to spread all that floor space out into a district of, say, four 50-story buildings and integrate them horizontally. What is the optimal massing of floor space in a dense district? Where is the parking?

Many world urbanologists argue that very dense districts save agricultural and other land from sprawl. But is highest best? What is the optimal density? What is the best floor-to-area ratio? How high is good?

There are advantages and disadvantages in super-high living. Better views, visibility and prestige for users and residents are some of the advantages. Higher is better for rooftop telecommunications stations. On the other hand, is it psychologically good to live so high? Isn’t a high structure more vulnerable to earthquakes and wind? It seems that more stability can be designed into shorter buildings integrated into a polygon of sorts, with APMs connecting them at one or more levels. More interesting strategies for parking also become apparent.

Integration in Perspective

Historically, cities had modest dimensions. Populations rarely exceeded one million, because citizens relied on walking. It was not until the 1800s that pressure for larger cities created intense demand for central spaces, hence incentives to build up. The elevator industry emerged in response to this pressure. Building height, limited by tolerance for climbing, rarely exceeded six floors.

Today, cities have grown larger, often exceeding populations of 10 million and creating horrible street and highway congestion with intolerable traffic accidents and carbon-dioxide (CO2) pollution. In contemporary automobile-addicted cities, towns and sprawled regions, parking requirements stretch large districts horizontally to dimensions that are unwalkable. On foot, it’s hard – almost impossible – to get around. In response to last-mile travel and delivery needs, the APM industry has emerged and needs to talk with the elevator world.

Where are the growth zones of tomorrow’s cities? Rapid growth is taking place in Asia, Africa and Latin America, where each year, cities are absorbing thousands of migrants from rural areas and small towns. In the U.S., growth is modest and selective. Some southern states – Florida, Texas, Arizona and California – are growing rapidly and are largely highway-oriented.

Yet, even in slower growing or stagnant areas – the U.S. Heartland, Great Lakes belt and Northeast – airport officials are looking for better ways to provide parking, serve car-rental operations, and connect to hotels and convention and event facilities. Security concerns make de-clogging airport roads a priority. Environmental concerns make shifting from CO2-spewing cars to electric transportation attractive. It is here where we will likely see progress in intermodal lobby design.

Medical and research districts are also growing in size and complexity. They have needs that a series of visitor-orienting lobbies interconnected by easy horizontal movements can satisfy.

Most metropolitan areas also have knowledge zones – districts with clusters of universities, colleges and research institutes – that create intense circulation needs and parking headaches. Other districts may be cultural and include museums, concert halls, etc. Yet others may cater to growing populations of senior citizens with their special needs and interests.

The future holds many opportunities for the elevator and APM worlds to interact. One opportunity this month will be in Arlington, Virginia, at George Mason University, where the Seventh Podcar City conference takes place October 23-25 (www.podcarcities.org). With mutually respectful synergy, APMs and elevators can help create urban areas that make for safer, healthier and more sustainable lives.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.