Emergency Access to Elevator Shafts

Apr 1, 2013

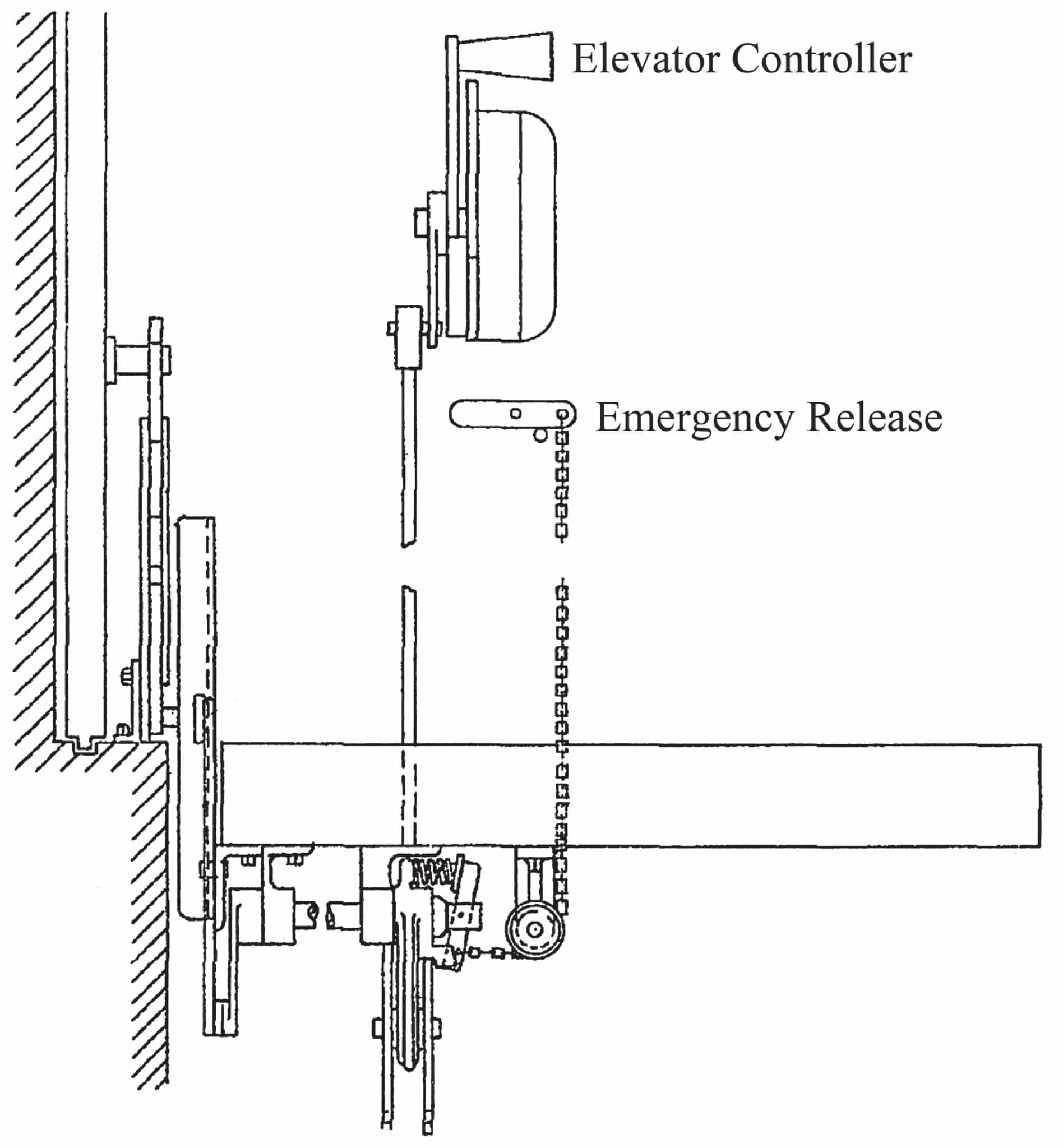

Last month’s history article, “A 1950s Haughton Elevator,” referenced a 1937 drawing that depicted an “emergency release” located in the hallway, was intended for “fire department and emergency use only” and which was operated by an “emergency door key.” The repetitive use of the term “emergency” highlights the device’s perceived importance and, perhaps, adds weight to a question about this device: when were emergency door releases first introduced and required by code? The answers will be explored through an examination of editions of the ASME A17 Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators published between 1921 and 1955 and the patent record for the same period. Like most historical inquiries, they are both simultaneously satisfying and frustrating in that they shed light on the past and prompt additional questions.

The first edition of A17, A Code of Safety Standards for the Construction, Operation and Maintenance of Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators (1921), included a definition and rule concerning emergency releases. The definition read, “An emergency release is a device the purpose of which is to make inoperative door or gate electric contacts or door interlocks in case of emergency.” The accompanying rule offered an explanation of the device’s operation and required location:

“Rule 118 Emergency Release

a.) The emergency release control shall be in the car, plainly visible to the occupants of the car and reasonably, but not easily, accessible to the operator.

b.) To operate the car under emergency conditions it shall be necessary for the operator to break a glass cover protecting the emergency release and to hold the emergency release in operating position. The emergency release shall be so constructed and installed that it cannot be readily tampered with or “plugged” in the operating position.

c.) Rods, connections and wiring used in the operation of the emergency release, that are accessible from the car, shall be enclosed to prevent being tampered with readily.”

This definition and rule clearly indicate the emergency release – as first conceived – had nothing to do with accessing the shaft or car from the hallway: it was intended to facilitate car operation during an emergency.

The logic behind this initial conception may have arisen from early efforts to define proper elevator usage during fires or other emergencies – efforts that were impacted by changes in elevator operation that occurred due to the introduction of door interlock systems. This supposition is supported by Edward L. Dunn’s 1924 Mechanical Interlock for Elevators (U.S. Patent No. 1,493,069). The patent application had been filed in 1921; thus, its content reflected attitudes contemporary with the first elevator safety code. According to Dunn (an engineer with Otis), an emergency-release mechanism was designed to be operated when a “panic or fire” occurred, “in which case, it may be desired to operate the car with open doors.” This statement suggests the elevator was to be used during an emergency to evacuate a building’s occupants. It also suggests the ability to operate the car with its doors open was beneficial, because it would increase passenger entry and exit times and allow for greater efficiency during an evacuation.

Dunn’s emergency-release design anticipated some of the 1921 code requirements in that it was “reasonably, but not easily, accessible to the operator”; however, its design omitted the protective glass case (Figure 1). In fact, this omission unknowingly anticipated one of the revisions that occurred in the second edition of A17, A Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators (1925). This edition included the 1921 definition; however, section “b” of the rule (now designated as “Rule 123”) was revised such that the glass cover was no longer required. The 1925 code also included “reference figures” identified as 0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 12 and 24, which were used to “indicate when such rules or paragraphs become effective when applied to existing installations.” Rule 123 Emergency Release was assigned a “0” designation, which meant the rule was “to be applied immediately.”

The third edition of A17, The American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators (1931), retained the 1921 definition, reverted to the 1921 code’s requirement of a protective glass cover, more precisely articulated the rule’s requirements and included a new section on testing:

“Rule 123 Emergency Release

a.) The emergency release shall be in the car, plainly visible to the occupants of the car and shall be easily accessible to the operator.

b.) The emergency release shall be provided with a break glass cover and with means for breaking the glass.

c.) To operate the car under emergency conditions, it shall be necessary for the operator to hold the emergency release in the operative position.

d.) The emergency release shall be constructed so that it cannot be readily tampered with or ‘plugged’ in the release position. Rods, connections, and wiring used in the operation of the emergency release, that are accessible from the car, shall be enclosed and protected from injury.

e.) Each make and type of emergency release shall be tested and approved by some competent designated authority as to compliance with a, b, c, and d of this rule and as to meeting the test for insulation as specified for interlocks in 121i, Test F.”

The structure of the revised rule, with its more precise separation of requirements and the addition of section 123e – requiring testing by a “competent designated authority” – reflected the continued refinement of A17.

The 1931 code also contained, under a separate rule, the first reference to a required means of accessing an elevator shaft or car from the hallway. Section 120j of Rule 120 Hoistway Doors for Passenger Elevators addressed two types of hallway access systems and keys:

“A service key shall be provided for the purpose of opening from the landing side, the hoistway door where the car is normally parked, but only when the car is at that landing. This key shall open no other hoistway door.

“An emergency key shall be provided which will open from the landing side and irrespective of the position of the car, the hoistway door at the landing where the car is normally parked, the lowest landing, and such other hoistway doors and emergency doors as are specified below. It shall open no other hoistway door. Such an emergency key shall be placed in a break-glass receptacle clearly marked ‘For Fire Department and Emergency Use Only,’ at the landing nearest the main entrance to the building.

“For an elevator operating in a blind hoistway (as is usually the case with express elevators), the first hoistway door above the blind portion of the hoistway shall be so arranged that it can be opened from the landing side by the emergency key specified above and irrespective of the position of the elevator car.

“If an elevator is installed in a single hoistway, the emergency key shall open all hoistway doors and where the elevator is installed in a single blind hoistway, then provision shall be made for emergency hoistway doors at every third floor, but not more than thirty-six (36) feet apart, to permit access to the elevator in the blind portion of the hoistway.

“Emergency hoistway doors shall be provided at every third floor to permit access to the elevator in the blind portion of the hoistway. Such emergency hoistway doors shall be not less than thirty (30) inches wide and (6) feet, six(6) inches high (clear opening), and shall be easily accessibleand free from fixed obstructions. The emergency key required above shall open all such emergency hoistway doors.”

The perceived need to have different keys for service and emergency access reflects elevator use patterns in the 1930s, when most systems utilized operators. The service key provided access to the car at a single designated location: “where a car is normally parked.” Operators, at the end of the workday or other designated times, often took their car out of service, “parked” it at a designated floor, and locked the controller and doors to prevent access. The emergency key allowed greater access due to the perceived need to respond to the various emergencies that could occur in or adjacent to an elevator shaft. It should be noted that the required language found in the 1931 code for use on the emergency-key receptacle is similar to that found on the 1937 Haughton drawing, which recommended the statement “Emergency door key for fire department and emergency use only.”

The fourth edition of A17, American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators (1937), and the revised fourth edition (published in 1945, which incorporated changes made in 1942) retained the original 1921 emergency-release definition and Rule 123 as stated in the 1931 code. However, Section 129j of Rule 120 Hoistway Doors for Passenger Elevators was revised to reflect the increased use of push-button elevator systems:

“A service key shall be provided to open the hoistway door from the landing side that the landing where the car is normally parked out of service, except for automatic operation and continuous-pressure-operation elevators. This key shall open this door only when the car is within the landing zone and shall no other hoistway door.”

As with earlier code revisions, this change also brought greater specificity to the rule and confirms the fact that the service key was intended for use only when a car was “parked out of service.”

Industry awareness of these rules and their implications for elevator use and design are found in Clifford Norton’s 1937 Elevator Door Mechanism (U.S. Patent No. 2,067,242). Norton (an engineer with Otis) noted “authorized attendants are furnished with service keys [that] enable them to gain access to the elevator car, while it is parked at the floors provided with service key mechanisms.” He also noted “an emergency or fireman’s key. . . is positioned near the hatchway entrance of each door provided with emergency mechanism. This key is preferably housed in a locked container with a “break glass” cover to ensure its use only in case of a real emergency.” And, he observed that best practice suggested:

“. . . a combination of both of these mechanisms be provided for at least one door, preferably the door at the ground floor, where the car is normally parked, and which usually would be the most advantageous entrance to the hatchway during an emergency.”

Norton’s patent also contained a detailed description of the two keys: the service key was to be “preferably of round circular section for insertion in a circular aperture,” while the emergency or fireman’s key was to be “preferably of lunar- or crescent-shaped section for insertion in a lunar-shaped aperture.” Although the differing designs required two points of access, the perceived benefit of this feature was that “neither key could perform the function of the other.”

Thus, by the 1940s, rules concerning emergency releases and service and emergency access systems had been thoroughly defined, and these code requirements had become accepted aspects of elevator-door design. However, the fifth edition of A17, American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators (1955), literally changed the rules of the game with regard to emergency access. Rule 123 (among several other related rules) was incorporated into a new set of rules under Section 111 Hoistway-Door Locking Devices, Car-Door or Gate Electric Contacts, Hoistway Access Switches, and Elevator Parking Devices. The title of Rule 111.11 Emergency Keys for Unlocking Hoistway Doors Prohibited clearly signaled the authors’ intentions toward these devices; the 1955 code also omitted all references to service and fireman’s keys.

However, the single line of text provided for Rule 111.11 suggested the topic of emergency access was not completely absent from the 1955 code: “Means shall not be provided or used to unlock hoistway doors from the landing side when the car is not in the landing zone.” This statement implies a “means to unlock hoistway doors” could be provided, as long as its operation required the presence of the car in the landing zone. Rule 111.10 Hoistway Access Switch addressed the means by which this would be accomplished:

“A hoistway access switch shall be provided for every power elevator at the top terminal landing to permit access to the top of the car, and at the bottom landing to permit access to the pit here to door at this landing is the only means of access to the pit.”

The remaining subsections of Rule 111.10 further defined the operation of hoistway-access switches. This information brings this investigation full circle in that it suggests similar questions to the one that prompted this month’s article: how did these switches work, how long were they required by A17 and what is their relationship to current practice? These questions will be explored in a future article.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.