The death of an industry worker on the jobsite is examined.

Following my column in Elevation 71 titled “Not our Finest Month,” I was contacted by a number of people in the industry who asked about the second accident I described in the article. The common response was that the industry needs to learn from incidents such as those on which I reported. I did not go into great detail about one of the accidents, because while writing, the inquest of Peter Knight’s death had only just finished at Southwark Coroner’s Court in London.

Over the years, I have been involved with the investigation of a large number of cases in which fatal accidents have occurred. However, this was my first time to provide evidence to a coroner’s court. I found the experience as daunting as giving evidence in crown and civil courts. I attended the locus with a number of professionals from the elevator industry, and after interrogating the data logger, we were quickly able to produce an accurate chronology of the events.

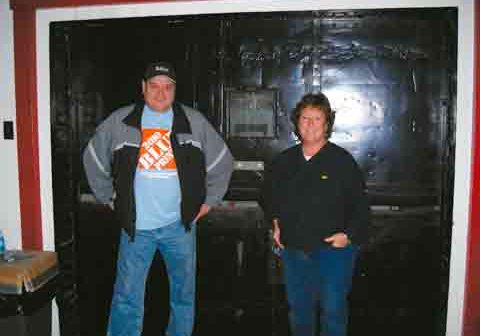

Knight, the deceased, was 26 years old and had been in the lift industry for approximately two years. He died on September 22, 2010, while performing routine work. Knight had been vacuuming in the pit. The engineer he was working with had left the area to get something. Upon returning to the lift, the car was at the ground floor, its doors open and the vacuum still running in the pit. Knight had sustained fatal head injuries and was found dead in the pit. The two obvious questions of “how” and “why” this happened had to be answered.

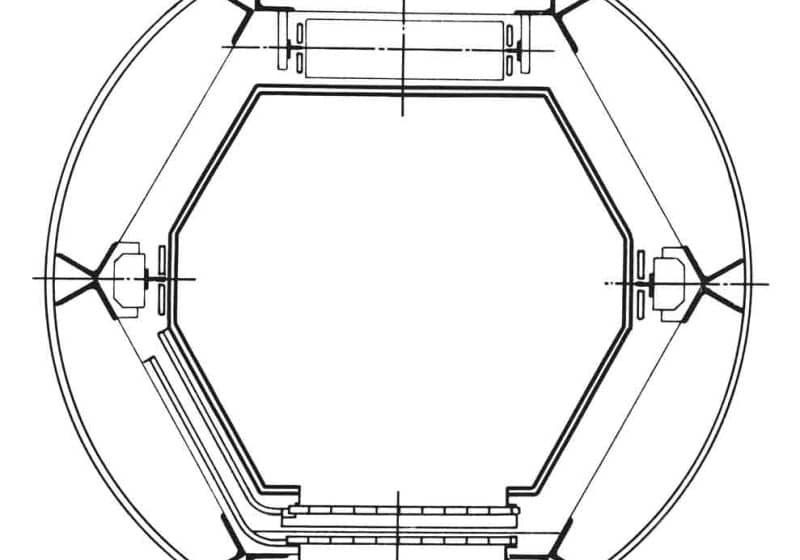

A commissioning process established that the lift was in good operating condition and all safety-circuit components were functioning properly. The process also proved the data logger to be working correctly and recording events as it was designed to do. Since nobody actually witnessed the event, there will always be a certain amount of speculation as to whether the landing door was closed purposely by the deceased, or whether it was closed by accident. However, the action of the landing door closing allowed the lift to perform a reset to the bottom floor. Again, this is speculation, but it is reasonable to assume Knight failed to hear the lift move, because he was vacuuming.

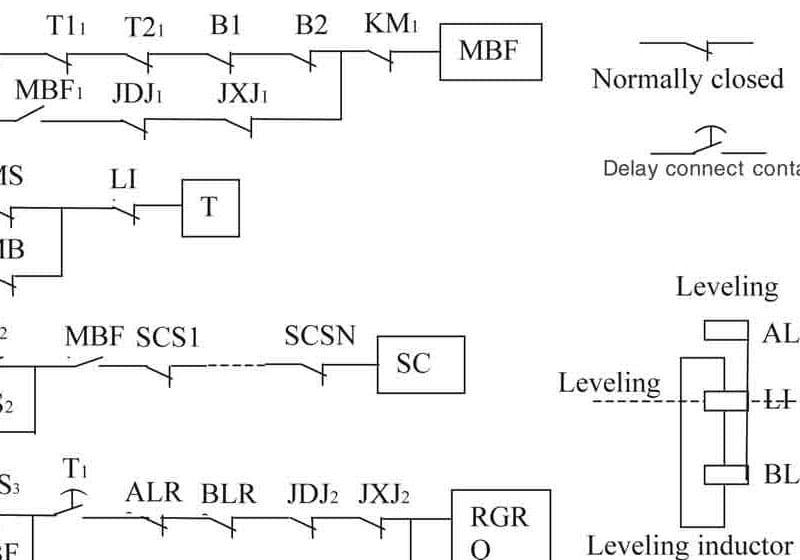

So, how could this happen? It was established by interrogation of the data logger that at no time had the pit stop switch been used. The immediate reaction is shock, because the industry knows the first thing you do before you get under a lift car is to protect yourself by proving the pit stop switch. As stated, the pit stop switch had not been operated at any time, so there had been no proving process, let alone use of it when in the pit. Note that this is a pit stop switch and not an emergency stop switch. It can be frustrating to see lift contractors refer to an emergency stop switch in this respect, because that is not its function.

BS7255: “Safe Working on Lifts” details safe procedures for working under lift cars. Perhaps Knight had not been trained properly. However, examination of the training records for both individuals revealed they had been trained to safely access a lift pit. In evidence, the engineer said he thought Knight had put the pit stop switch in. It is clear, though, that we are responsible for our own safety and for the safety of others. The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 is very clear in this respect. The rules are simple – if you are getting in the lift pit, make sure you are protected.

The next question that comes to mind involves the use of a door blocking device. Why was one not used? Again, upon investigation it was established that the workers had been issued with door blocking devices and, yet, they chose not to use them. I, and others, trawled through the documentation associated with the contract and could find no fault with either the lift contractor or the lift owner; therefore, the lessons published in Elevation 71 stand firm for me and are directed toward operatives in the field:

- Make sure you communicate clearly.

- Do not take shortcuts.

- Follow procedures.

Unfortunately, the failure to follow procedures and not use equipment provided meant this accident was predictable. I hope others will learn from this simple mistake, because it could have been so easily prevented. As a result of this case, I will be organizing a Lift Academy presentation that will focus on section 5, which is about the responsibilities of persons working on lifts. As with all Lift Academy events, there will be no charge to attend. Anyone from any position and company are welcome to attend. A tragic accident like this should never happen again. We must do everything we can to avoid it. My experience in the witness box at the coroner’s court was not pleasant, and everybody involved with this case has it inscribed in their minds.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.