Haughton Elevators (1923) Part 1

Nov 1, 2024

Company catalog describes and illustrates elevator components and more.

In 1923, the Haughton Elevator & Machine Co. of Toledo, Ohio, published a 32-page illustrated catalog designed to introduce prospective customers to their product line. Woven into this introduction was a clear rationale regarding why prospective customers should engage directly with the company:

“Your medical specialist cannot prescribe for you until he makes a diagnosis of your case. We are elevator specialists, and cannot prescribe the proper elevator equipment for your building until we make a study of the building, its size, character, purpose, power available and loads to be carried. The standardizing of passenger and freight elevators has not developed to a point that enables giving enough detail in a catalogue to allow owners or engineers to select the proper elevator or determine its price. This catalogue is, therefore, intended to present purely in a general way the facts about Haughton Elevators and The Haughton Elevator & Machine Co., and to give some idea of the Haughton principle of design, type of installations, service to customers and engineering assistance available.”[1]

Haughton’s equating a vertical-transportation (VT) specialist with a health care specialist served to raise the professional profile of their employees and, as did the claim that there was limited standardization of VT solutions, highlighted the importance of hiring a qualified VT professional to solve each building owner’s unique problem.

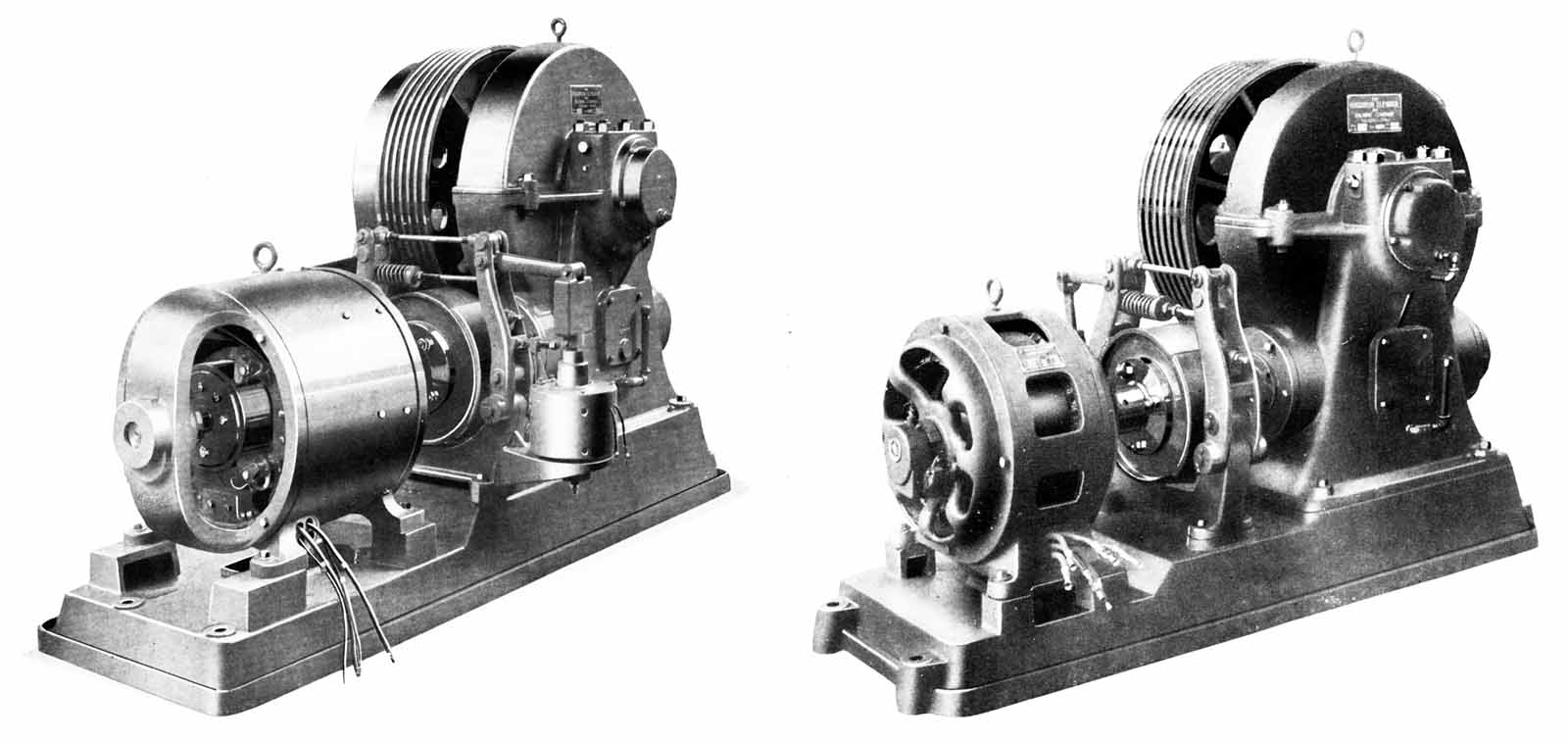

In their attempt to present the “facts” about Haughton Elevators “purely in a general way,” the catalog’s authors faced the challenge of balancing the inclusion of technical information (desired by engineers and architects) with non-technical information (desired by building owners). This balance is evident in the description of Haughton’s single gear V-groove traction machine:

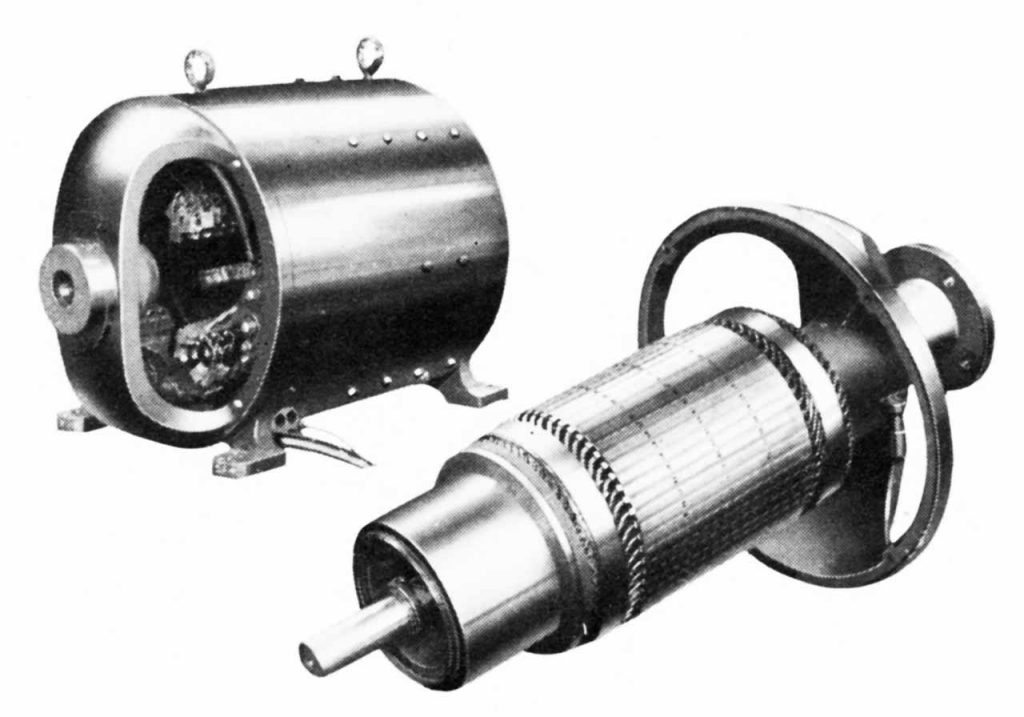

“Haughton Elevator engines are of the direct connected V-groove Traction type, the gearing and motor being mounted on a heavy cast-iron bed plate, assuring perfect alignment. This type of engine is built in many sizes, making it possible to obtain the proper size for any specified duty. The variety of sizes allows a selection of car speeds from 25 ft/min to 700 ft/min, and capacities ranging from the lightest load to the heaviest. Haughton Elevators have been installed to lift 50,000-lb live load. These machines have proved the most economical and the most efficient for high-speed service. Only the best materials and workmanship go into Haughton Elevators. Current consumption is lower than that in other types, and total maintenance cost is considerably less. Haughton Elevators are noted for their flexibility of control, rapid handling at floors and smoothness in operation. The worm gearing is cut with extra care on precision machines specially designed for the purpose. This accounts in part for the smooth-running qualities of Haughton Elevators. The bearings are adjustable and removable so that gears may be adjusted to suit conditions without the necessity of tearing down the engine. New bearings can be installed without shutting down the equipment for any great length of time. All bearings are of the chain oiling type, with large oil reservoirs and drip pockets to catch any excess oil which might work out. The reservoirs are provided with filling and drain plugs to allow oil to be drained and replenished easily.”

The emphasis on the engine’s ease of operational maintenance highlights an additional theme found throughout the catalog. This description also included a summary of the elevator’s overall specifications (which noted that it was available in five sizes):

- Range of horsepower capacities: 5 to 60

- Range of capacities (live loads): 1000 lb to 30,000 lb

- Range of speeds: 25 to 700 ft/min

- Brake: Electrically released

- Current: Either alternating or direct

- Bearings: Drum and gear shaft used Haughton patented adjustable bearings

- Worm Shaft: ball thrust

Lasty, the illustrations that accompanied this information echoed this mix of general and specific information: They included images of a large and small single gear engine and a detailed image of a worm gear (Figures 1 and 2).

In addition to elevator engines, Haughton also manufactured electric motors (alternating and direct current) and controllers (alternating and direct current). The majority of these systems and components were described as the result of years of R&D, as was evident in the description of their direct current motor (Figure 3):

“In direct current motors, we have also conducted a great many experiments and our experience has been even longer than with the alternating current type. These motors are of especially rugged and liberal design so as to stand the severe requirements of elevator service. There are three different designs: the single-speed motor with speed control by armature resistance, the multi-speed with a 200% speed change by shunt field and the multi-speed with a 300% speed change by shunt field. The single-speed motor with speed control by armature resistance is used for the slower speed service and in cases where it is necessary to keep the first cost as low as possible. Those with speed change of 200% by shunt field are used for moderate speed service, because of more accurate floor stopping. Those with speed change of 300% by shunt field are used for high-speed service and for all service where very accurate floor stopping is essential, or where automatic floor control is desired. The shunt control motors are somewhat more expensive in first cost, but give very positive slow speeds and are much more economical in power consumption.”

This description is of interest because it appears to indicate that not all Haughton elevators were equipped with automatic leveling devices. The statement that their motor designed for high-speed service was intended for settings “where very accurate floor stopping is essential, or where automatic floor control is desired,” suggests that automatic floor control was an optional feature. Although this was a relatively new VT industry innovation, Haughton’s apparent decision not to provide it on all of their elevators is intriguing.

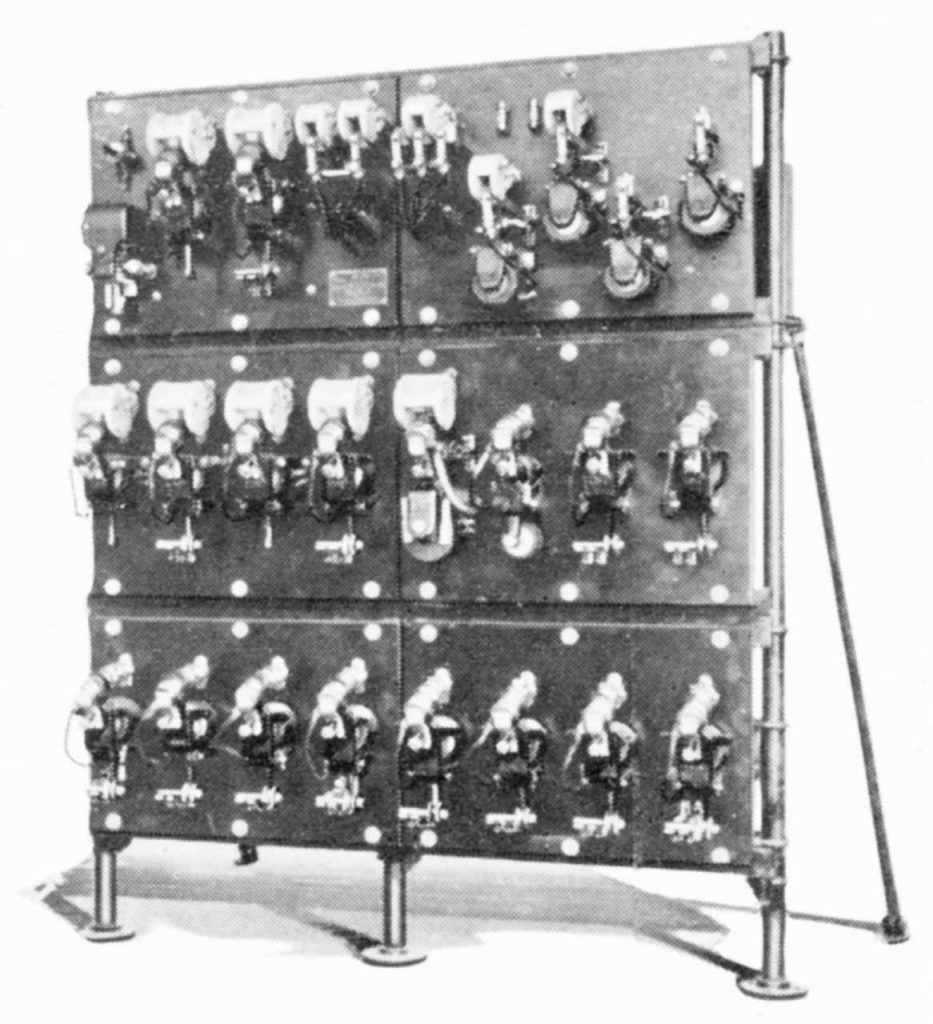

The description of the company’s direct current controllers also emphasized their careful development over time (Figure 4):

“Haughton direct current controllers, like the alternating-current controllers, have been developed along individual lines, drawing upon the experience of many years in direct current installations. All power contacts are copper to carbon and are liberal in design, so as to reduce maintenance cost to a minimum. They are built for all methods of control desired and for single-speed and multi-speed motors. Like the single-speed motor, the single-speed controller is much cheaper in first cost; but like the motor, its use is recommended only for the slower speed service. The controllers for the 200% and 300% shunt field control motors are somewhat more expensive in first cost, but when power economy and more accurate floor control are necessary the greater initial cost is soon offset by the gain in economy and efficiency of operation. On our controllers for moderate or high-speed service we use double the customary number of starting steps, which is one of the reasons why Haughton Elevators operate more smoothly than others.”

This description echoed that of their shunt-controlled motors in noting the higher first cost while emphasizing their long-term “gain in economy and efficiency of operation.” In fact, a section of the catalog, titled “Proof of Efficiency,” was devoted to this topic.

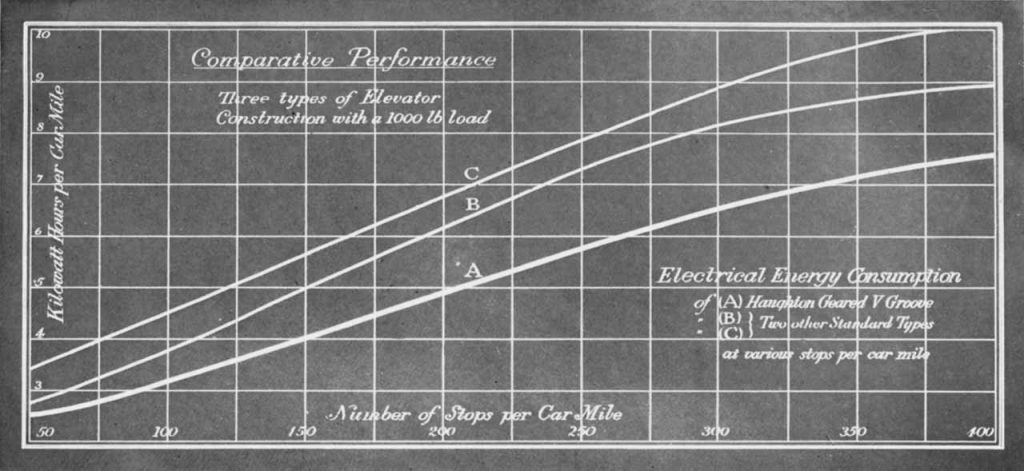

The primary feature of this section was a chart that illustrated data gathered during “a series of 50 tests on actual installations of the three different principles of passenger elevator construction, the same engineers and test instruments being employed throughout.” While the descriptive statement “three different principles of passenger elevator construction,” is somewhat ambiguous, it may be safe to assume that it refers to elevators built by rival companies. An equally safe assumption is that the companies were most likely Otis and Westinghouse. The chart measured kilowatt-hours per car mile against the number of stops per car mile, for cars carrying a 1000-lb load (Figure 5). The Haughton elevator, line “A” on the chart, was clearly the more energy efficient machine. According to the catalog text:

“Much of this saving is accomplished by the Haughton method of retarding and stopping the motor, which not only saves current, but also ensures accurate floor landings and thereby eliminates current waste in jockeying for floors. Besides the saving in current there is also an important saving in time, increasing the service of the elevator.”

Haughton also noted that the “power saving … increases with the number of stops, which in the case of most passenger elevators range from 150 to 300 per car per mile.” Critical information missing from the description of these comparative test results includes the building height and number of floors served, the building type (office, etc.), the number of elevators tested and the method of measuring current used by the machines. Haughton was, of course, not the only manufacturer to conduct efficiency tests, and a future article will explore this VT industry practice.

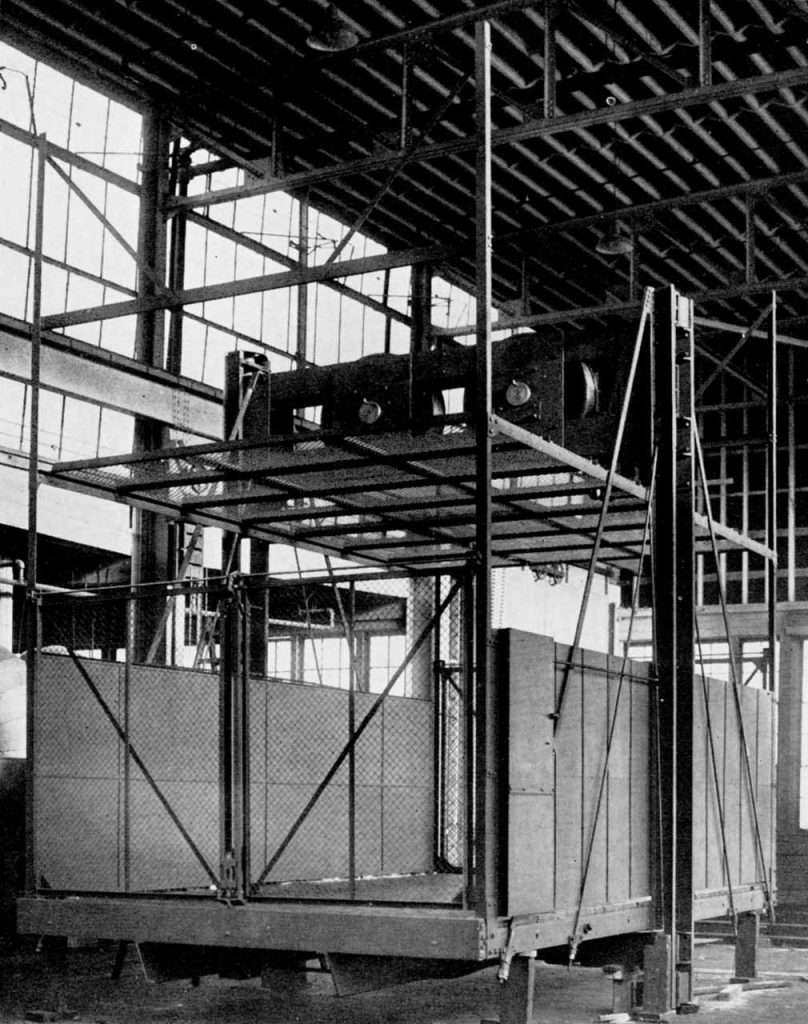

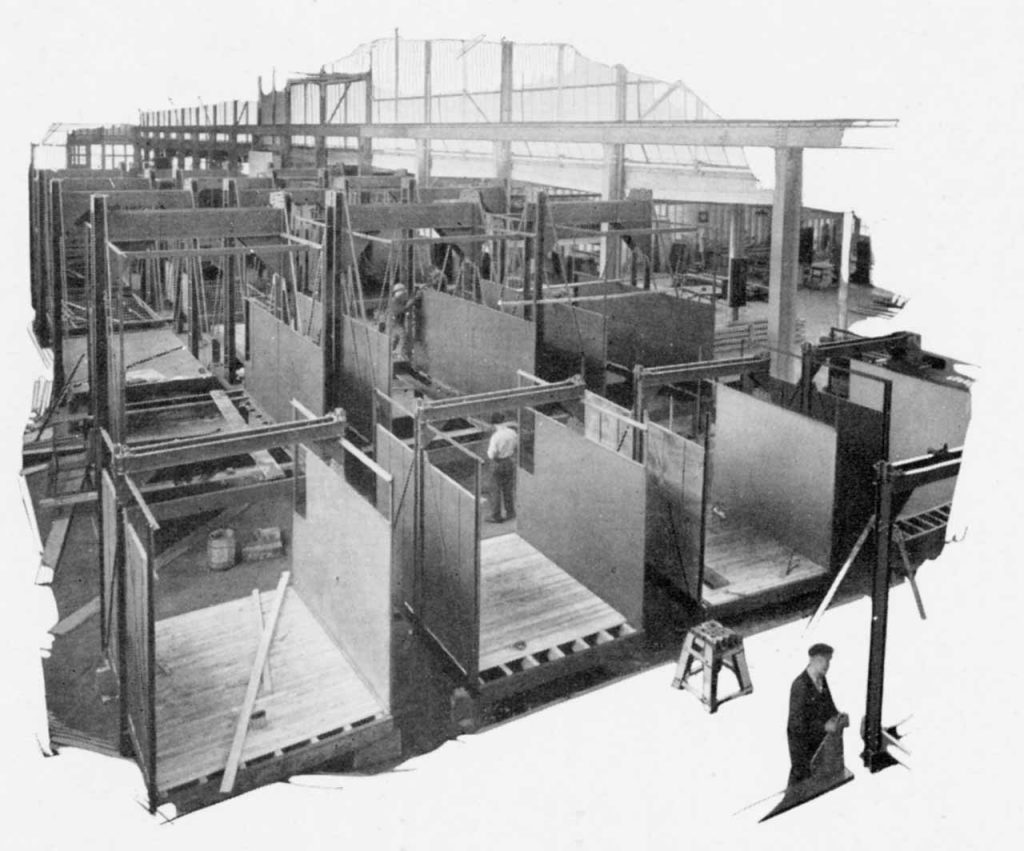

The range of Haughton products also included elevator cars and a full complement of safety devices. Although they built passenger and freight cars, the catalog focused on freight cars due to the fact that freight elevator production comprised the majority of their business. The following description accompanied a photograph of a completed freight car on their factory floor (Figure 6):

“Heavy construction means long life. All Haughton cars are built to withstand over-loading and severe service. Haughton has built cars up to 14’0” x 30’0”, and for capacities up to and including 50,000-lb live load. The gate shown on the car above is equipped with safety catches to keep the gate from falling in case the cable breaks. This gate is arranged for power operation by use of the Haughton Patented Electric Gate Operator. This Electric Gate Operator also operates the landing gates or fire doors. Many of the large industrial plants use Haughton Gate Operators because of increased speed in handling at the floors.”

The catalog text noted that these cars were built “under supervision of Haughton engineers,” and that “a large section of the plant is devoted entirely to car building” (Figure 7).

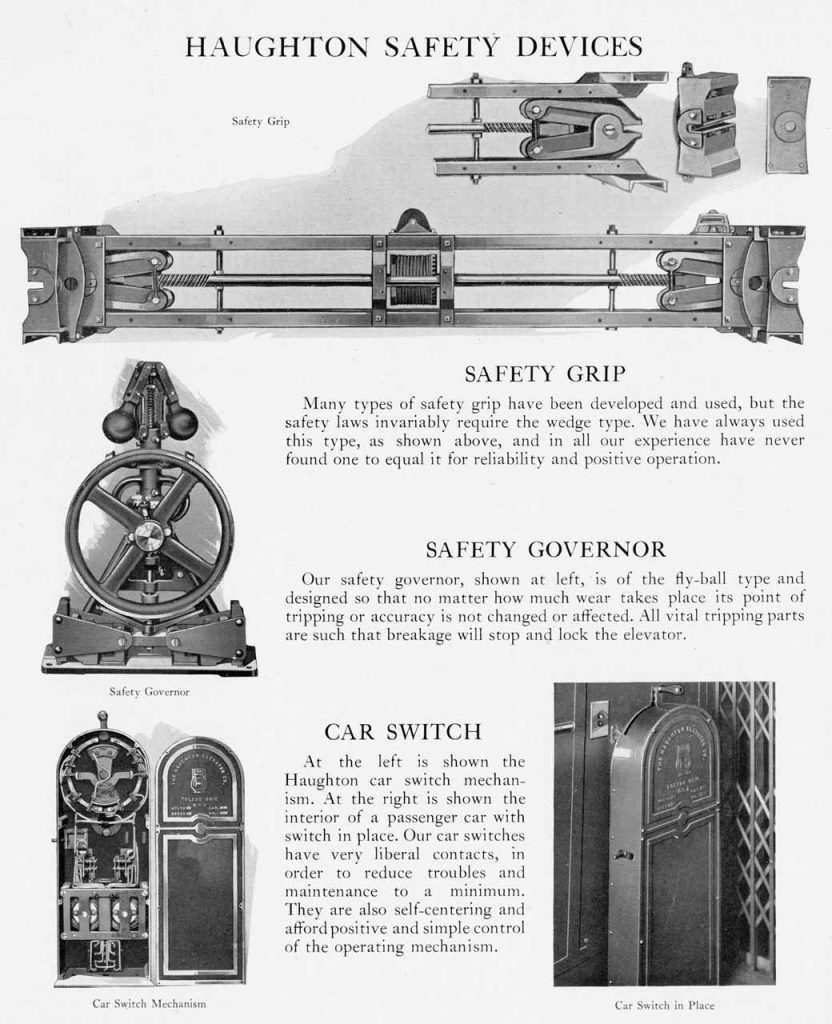

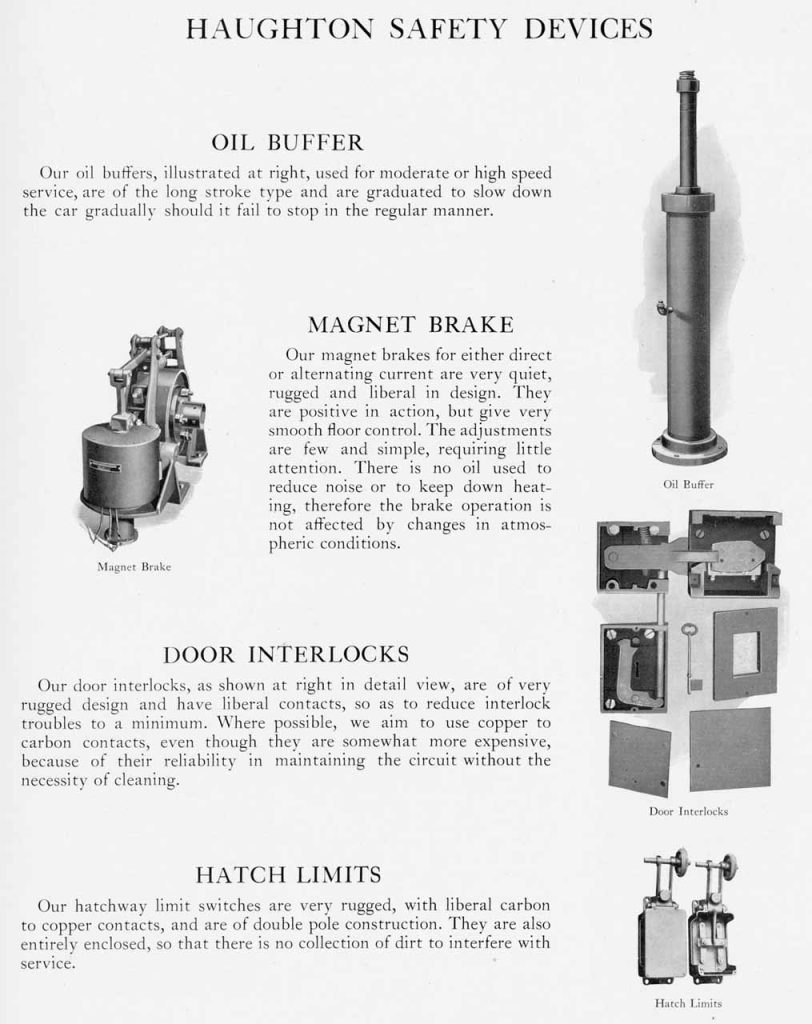

Haughton’s range of safety devices included wedge-type safety grips, fly-ball governors, car switches, oil buffers, magnet brakes, door interlocks and hatch limits (Figures 8 and 9). The company noted that its use of the wedge-type safety was due, in part, to the fact that most “safety laws invariably require the wedge type.” The company also reported that it had “always used this type … and in all our experience have never found one to equal it for reliability and positive operation.” In the essential design and operation, Haughton’s safety devices followed normative industry standards and illustrated VT state-of-the-art in the early 1920s.

In addition to describing and illustrating Haughton elevator components, the catalog also included a detailed guide to the writing of elevator specifications, as well as information on ropes, elevator speeds, the typical space required for floor and overhead installations, elevator lubricants and Haughton’s post-installation services. The conclusion of this article will examine these topics.

Reference

[1] Haughton Elevators, Haughton Elevator & Machine Co. (1923). Note: All quotes derive from this source.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.