Liftscapes

Nov 1, 2018

Artist describes his commissioned work in elevators in a 16th-century Swiss structure and 14th- century German castle, both now homes.

Europe has an abundance of historical sites and castles, some dating back before medieval times. Once trading houses, seats of clerical authority and homes of reigning sovereigns, many of these structures have been altered over the years. The modern world views them with an attitude of romantic nostalgia. Despite their differences, these premises had one thing in common: occupants had to climb narrow, often winding stairways all the way up to the castle keep. Without distinction of person, rank or ancestry, everybody had to crest these elevations by ordinary, exhausting footwork.

Today, some of these buildings have been turned into private homes, including the former bailiwick, or residence, of the equivalent of a modern-day sheriff in Riehen, a prosperous village near Basel, Switzerland. The building, dating to the 16th century, is one of the most precious architectural treasures in the entire Canton of Basel, a former sovereign state that spans 37 km2. It is adjacent to a medieval fortress church, with which it forms an extraordinary, unimpaired historical ensemble. Even today, it hearkens to the wealth and power in rural Switzerland.

This old prefecture is now inhabited by a family of design manufacturers who own one of the world’s most famous furniture companies. One of the most important concessions to modernity the family added to their house was a lift to connect all four floors, from wine cellar to attic guestrooms. There was a battle with monument authorities before the lift was approved, but from then on, it would enhance the residents’ comfort by preventing them from carrying all the everyday transports up and down the numerous staircases. Although making daily life much more comfortable, the elevator’s sparse appearance, which stood in stark contrast to the family’s highly visible connoisseurship in modern art and design, did not please the lady of the house.

Sometime in the 1990s, the Littmann Gallery in Basel hosted a show of my work. The aforementioned lady of the Riehen Bailiwick attended opening night. The show, titled “The Rembrandt Lounge,” was a kind of assembly of contemporary artwork on the border between art and objects of utility. That same evening, I was invited to the house to look at its lift. After inspecting the cabin and talking with members of the family, I was commissioned to visualize a

“wall painting for a lift,” seemingly a novelty in the arts, as well as in the history of traditional lift design.

It was also a novelty to my portfolio, and, lacking an adequate classification for these mobile artworks, I merged the terms “lift” and “landscape” into “liftscape,” as it precisely describes this type of interior project. The lift in Riehen would, thus, become the first of its type, or, simply, “Liftscape #1.”

Conceiving Liftscape #1

A lift is a secluded space in which we travel from one location to another. Barring some mishap, the journey’s duration and direction is unalterably determined. When such a lift is turned into a work of art, its sight is subject to different rules of perception than when visiting a museum where artworks can be contemplated for any length of time and in any order.

I immediately understood the cabin of a lift as a way to be completely enclosed by a work of art. The art moves with its passengers in time and space for brief periods but, itself, is still. It is a kind of artistic synthesis, reminiscent of Kurt Schwitters’ The Merzbau, a famous piece (destroyed in World War II air raids) that inspired many an installation artist. The customary long, contemplative view is altered into fragmented bits of perception that are brief but repetitive during daily routines. I created a design that would correspond with these brief travels in time and space, inventing a world that echoes the past, present and future, shifting moments into layers, suspending the only rule of the journeys’ ups and downs.

The presentation allows the passenger to always grasp something new during these sequences of “floating.” Coated with a heavy-duty transparent varnish, the overall painting looks as fresh as on the day it was executed, despite five children growing up in the household.

Medieval Castle Provides Inspiration

Years later, another opportunity for lift painting arose at Dreckburg, a medieval, moated castle in Salzkotten, Germany. Its name is derived from “trecking,” as the castle was a milestone on the eastern-bound Old Salt Road used by salt merchants. The castle was once owned by the Earl of Westphalia, but later acquired and inhabited by Erhard Christiani, a museum architect.

As with the lift in Switzerland, the owner was not pleased with the formal extraneousness the elevator generated inside the romantic building until he heard about the artist who seemingly could bring it all together: the old and the new, the motion and the still.

Within three weeks of daily painting, I changed the elevator´s strangeness into an indissoluble part of the ancient heritage, as if the lift had been there even before the castle.

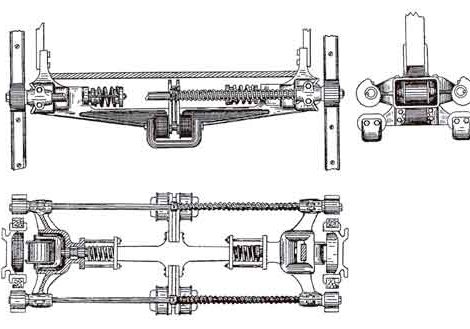

After presenting a draft true to scale, I was commissioned with its execution. Within three weeks of daily painting, I changed the elevator’s strangeness into an indissoluble part of the ancient heritage, as if the lift had been there even before the castle. A camouflage pattern alters the painted parts of the cabin from the cool, steely surfaces, turning the former into lookalike fragments of an old tapestry that seemingly once covered the walls.

This artifice reverses the perception of what was first, the lift or the castle? Now, the steely areas appear as if they are located underneath the painted parts, as if stripping the painting has revealed a concealed technical structure from times long past. Not only that, suddenly, the limited dimension of the cabin merges into the imagination of another spacious castle hall, with the painting telling about a once surrounding waterscape into which the fortress was once built.

Liftscapes #1 and #2 are both still in use. Due to the privacy of their locations, visits could only be arranged by appointment.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.