Traditional systems’ younger sibling is gaining acceptance worldwide, but does it have staying power?

One of your reporter’s first assignments for ELEVATOR WORLD was writing about the modernization of the roped hydraulic elevator system in the 16-story Waterman Building, one of the first “skyscrapers” in Mobile, Alabama. The system was originally installed by EW founder William C. Sturgeon. KONE handled its recent overhaul and led your reporter on a tour. A highlight was the top floor’s expansive machine room, which was treated by project managers with a kind of reverence: the room holds both the brawn and brains of the system — the big, powerful machines (original to the 1940s) for hoisting the heavy steel cables and the controllers for telling the units where to go.

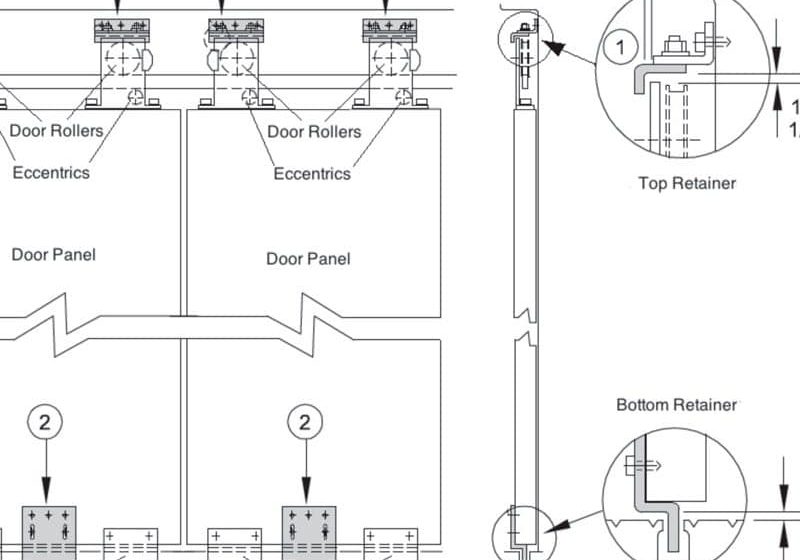

Were the Waterman built today, chances are, it would lack this 35- X 20-ft. room. That is because machine-room-less (MRL) traction systems — which have smaller machines located in their hoistways — continue to gain popularity in most parts of the world as they become the system of choice for low- to mid-rise buildings. They eliminate the costs associated with a machine room and create more leasable or sellable space — a win/win as far as property owners are concerned. They are also touted for their energy efficiency and environmental friendliness, since they do not require potentially hazardous oil.

Although it is more fun to think about the superfast, super-powerful vertical-transportation systems in the world’s glittering supertalls, the reality is that most of the world’s buildings are low to mid rise. It is where the profit lies. “More than 99% of the European building stock is less than six stories, approximately 75% of which is four stories or less,” says Dr. Ferhat Celik of Germany’s Blain Hydraulics. “The world’s building stock will more or less have the same tendency.” This, coupled with certain economic trends, aligned the stars for MRL systems, Celik says. “Energy bottlenecks and high oil prices of the last 15 years, together with good marketing strategies of the multinationals, have shifted the trend toward MRL [units] in low-rise buildings,” he observes.

Mariano Escobal, Engineering manager at Delaware Elevator in Salisbury, Maryland, says MRL systems are limited to 300 ft. or less of travel for several reasons. One has to do with rope life:

“All MRL applications are single-wrap with 2:1 roping, which means the rope speed will be high, two times the car speed. Groove pressure will also be high because of the single wrap. These two factors can shorten the rope life substantially and that is why [MRL systems] are not practical for high-rise applications. For travel of 300 ft. or higher, machine room double wraps are a must for long rope/sheave life.”

Another factor is sheave shaft load (SSL) capacity, he says. High-rise applications require heavy cars, ropes and compensation weights, which typically is beyond the SSL capacity of small MRL machines.

Describing them as the biggest energy-related game changer the elevator industry has ever seen, analysts covering KONE observe:

“The elimination of a dedicated machine room enables energy savings of 50-70%. KONE pioneered MRL elevators with the launch of its MonoSpace® model in 1996. Schindler was quick to follow with a launch in the same year, but Otis and ThyssenKrupp lagged by four and eight years, respectively. Today, MRL elevators account for over 40% of the installed base of elevators and 75% of new installations.”[1]

Mary Ryan, senior product manager, New Equipment, Otis North America, states:

“Fitting all equipment into the hoistway has become an expectation for many customers. Building space is of critical importance to our customers, and with our machine-room-less HydrofitTM (which uses hydraulic technology with a pump and valve to control the flow of oil to the pistons) and Gen2® (gearless traction system using coated steel belts to improve ride quality), we allow architects and buildings to use their space in a more productive way.”

Otis introduced Gen2 in 2002 and Hydrofit in 2011, and Ryan said sales of both have grown in the years since.

Responding to demand, many independents now offer their own MRL systems, and MRL R&D is continuously underway, regardless of whether one is an OEM or independent. “It’s a matter of keeping up with the Joneses,” says Charles “Pete” Meeks, president of Delaware Elevator, which, in response to demand, is developing an MRL elevator the company hopes to roll out by the end of 2015.

Meeks would prefer to produce strictly traditional systems. “We still feel that the tried and true method of a standard non telescopic, single-stage, holeless hydraulic elevator or in-ground hydraulic direct-acting unit is the best application for a low-rise elevator for quality, longevity, safe access and costs related to service and installation,” he says. “MRL [systems] may have a place, but it’s always our last recommended option to our customers.”

MRL systems have definitely found a place among customers of Quebec City, Canada-based Global Tardif (GT), one of North America’s largest independent manufacturers. Providing both passenger and service MRL units, GT debuted its customized MRL applications in 2002, and sales have grown from only a few that first year to approximately 30% of GT’s annual sales today. GT has hundreds of MRL elevator customers, and plans to release its newest model, the ultra-compact GT MRL EVOLUTION, by summer 2015. It projects sales volume for EVOLUTION to reach up to 300 units within the next two years.

KONE reports MRL elevators were first embraced in Europe, the Middle East and Asia-Pacific, excluding India. The most significant shift from roped hydraulics to MRL systems occurred from 2011-2012, according to KONE.

Mohamed Iqbal, managing director at Toshiba Elevator Middle East LLC, has observed the rise of the MRL elevator, particularly in the Middle East, where practically all installations — except large-capacity ones in tall buildings — lack machine rooms. He says South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation nations have been slower to accept MRL systems, but that is starting to change. “Since MRL [units] are a new addition to elevator technology, some designers and consultants have been reluctant to implement them due to code, safety and maintainability concerns,” he says. “But, in recent years, it has increased in sales due to its advantages.”

MRL elevators continue to gain popularity worldwide. The level of acceptance they enjoy, however, depends on which part of the world one is in. In Europe, for instance, MRL units have had an easier path than in the U.S., thanks to a more uniform and flexible code. Achim Hütter, who owns Achim Hütter Consulting in Hamburg, Germany, elaborates:

“The first European Lift Directive from 1996 offers different paths [by which] to secure a safe elevator. You can either follow a harmonized norm (within the EN 81 family) or decide to follow your own design which has to be approved by an accredited Notified Body. Consequently, MRL [units] found a relatively easy way into operation. Also helpful is the fact that European legislation becomes automatically adopted in its member states once they have been listed in the official journal.”

John Koshak of Elevator Safety Solutions LLC in Tennessee points out that another factor was at play. In North America, he says, hydraulic systems outnumbered traction systems 7:1 until 2000. In Europe, there were no direct-acting hydraulic systems, so the transition to MRL systems was simpler. “The transition was simply a traction [elevator] with or without a machine room — an easier gap to bridge,” he says.

Hütter adds that since individual U.S. states are not required to adopt every new code, “a mosaic of different stages of the A17 code” has emerged. During this time, murmurings of discontent have also begun to be heard. Critics maintain MRL systems are, at best, a hassle to maintain and, at worst, dangerous for mechanics and, potentially, passengers. They also point out their lifespan is considerably shorter than that of an old-fashioned hydraulic system. To be fair, they say, that is a trend that stretches far beyond elevators — to smartphones, household appliances and more. Hütter observes:

“All these products designed 20 years ago had roughly double the lifespan than that of their succeeding models. The need of small drives in small headrooms accelerated this development for MRL [units]. Sheetmetal thickness and duty cycles are reduced to minimize the diameters of the ropes, the diameter of the sheave and the size of the motor. All the action taken results in a [shorter] lifespan for elevators nowadays.”

Richard Baxter, who owns Texas consultancy Richard E. Baxter & Associates LLC, estimates the lifespan of most MRL systems in the 15-20-year range. He agrees that equipment is not as robust as it once was, thanks in part to the electronics they contain. He recalls a recent discussion with a salesman from one of the major OEMs: “He said his company is beginning to tell customers to be ready to change elevator equipment just as you do your computer equipment,” Baxter says. “He said their company would be obsolescing equipment in 10-15 years. I don’t believe this is unique to MRL elevators — I believe it is the new norm.”

In California, state officials are mulling changes to the code aimed at ensuring mechanic and passenger safety. California Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) spokeswoman Victoria Maglio says that in MRL elevators, there is a lack of egress and ingress if elevator professionals become stuck in the hoistway. Cal/OSHA, the division of DIR overseeing programs promoting public safety on elevators, amusement rides, and ski lifts, started to notice MRL designs with so many major elements in the hoistway that workers servicing the equipment were put in danger. Dan Barker, senior safety engineer for Cal/OSHA’s Elevator Unit, opines: “If the elevator isn’t safe to maintain, then it isn’t safe to ride.” A decision on the changes could come as early as the end of 2015

Until then, many in California are taking a wait-and-see approach. The state requires elevator systems to have machine rooms, and all companies that have had MRL systems installed there have had to obtain variances. Tom Shield of T.L. Shield & Associates of Thousand Oaks, California, says the variance process is initially arduous, but gets easier each time one does it. It’s naturally easier for the majors, which have the legal and technical manpower to quickly work out such details. As for his company, Shield says, “Right now, we are staying away from MRL [systems] until the state figures out what it is going to do.”

Meeks says he misses the workplace clearances and “common sense” safety factors prevalent in the designs of the systems of yesteryear. With MRL systems, he says, those regulations are fewer. Manufacturers maintain that safety is priority number one regardless of what kind of equipment they are producing. Meeks also says owners of MRL systems eventually stand to “get bitten and stung by higher maintenance and service costs.”

Also uneasy about MRL systems is the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In a bulletin issued in October 2014, the corps listed the following concerns:

- Lack of a working space for mechanics to adjust and repair the system

- Risk of electrical shock and arc-flash hazard due to 480-VAC electrical components associated with the drive motor being adjacent to the elevator doors

- Risk of being struck by the elevator while performing maintenance or repairs

- Nonstandard equipment for minimally extended hoistways that lacks servicing training, resulting in additional parts and service costs

- The fact that there are many non-MRL systems that are energy efficient

Adding to the uneasiness, there are examples of product incidents. While at least one model was discontinued, manufacturers have addressed issues with products that remain on the market.

Despite these murmurs, MRL systems are likely here for the foreseeable future, since there is more agreement than discord about them. In North America, for instance, “The train is long and heavy and will likely not stop quickly, since all the major companies — with the exception of ThyssenKrupp — have made their primary product offerings MRL intensive,” Koshak says. As for safety, that will likely remain shrouded in mystery since public reporting of safety statistics is limited, he says. Koshak states:

“It is not until a product cycle times out and the results are in before a handful of industry professionals can rate the efficacy of any design. That is to say, when 20 years has expired, we can ask, ‘Did the product meet its design expectations?’ There have been some early MRL designs that didn’t make the cut. The ones that have continued in production are the ones that will need this scrutiny.”

Hütter says he believes most would agree hydraulic, machined systems are superior, at least from a technical standpoint. However, when all factors are taken into account, it seems clear that MRL systems have gained a foothold in our elevator world — one that is unlikely to go away anytime soon. Nevertheless, Hütter says he prefers hydraulic systems, even in low-rise buildings, due to their “simplicity, low maintenance and repair friendliness.”

References

[1] Philip Wilson, James Moore, Louise Greenwell, KONE. “Chinese Whispers,” Redburn Research, September 8, 2014.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.