A summary of how the elevator codes affect NYC units and a rundown of the major compliance mandates on the horizon

by James Marinelli, Electrodyn Systems Ltd.

New York City (NYC) has always been a unique place to live and work. From its stone canyons, comprised of some of the world’s most famous skyscrapers, to its public transportation, responsible for delivering millions of people to their place of employment every day, the city has provided a daunting challenge to those of us responsible for vertically transporting the public to their lofty destinations.

It is often said that there is more vertical traffic than horizontal traffic in the city. The vertical-transportation industry in NYC is one of the largest in the world and, as such, is home to some of the oldest, most diverse and complicated elevator systems our industry has ever devised.

The vertical-transportation industry in NYC is one of the largest in the world and, as such, is home to some of the oldest, most diverse and complicated elevator systems our industry has ever devised.

As a direct result of this diversity, our elevator code requirements are unique, as well. In addition to the adoption of the ASME A17.1 Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators, modifications have been implemented by the NYC Department of Buildings to address the special requirements of a city of some eight million people. While the A17.1 has been modified to meet our local needs, from time to time, the NYC Elevator Code Committee has had to lobby the city council to adopt additions to the NYC Building Code to address catastrophic events that have occurred. This is not a new concept but a practice that has been used since the adoption of the first building codes. As a member of the National Code Committee, I have been involved in several code changes made to address such events. The best example of this is found in the aftermath of the MGM Grand fire, which took place in Las Vegas on November 21, 1980. During that horrific event, many lives were lost that could have been spared if the code had addressed some of the areas that were left to chance, like an “Alternate Recall” landing.

The New York Elevator Code is a modified version of ASME A17.1. It is referenced by Chapter 30 of the NYC Building Code, and the provisions of ASME A17.1 are modified in accordance with Appendix K, Chapter K1. The NYC Elevator Code Committee, for the most part comprised of professional engineers and consultants, has been entrusted with the task of keeping our local code current by adopting the latest version of A17.1 on a three-year cycle.

The committee is further tasked with amending A17.1 to keep up with the changing technology and events that shape our local industry’s needs. As a result of some recent events, new code requirements have been proposed, and, to date, several have been adopted by the city council. Several major new requirements have been adopted in recent years to address issues that have been brought into focus by events ranging from metal fatigue, frozen brake plungers, up overspeeding, broken door relaying cables and human error. Mother Nature has even gotten involved, with the flooding of Battery Park and the surrounding buildings.

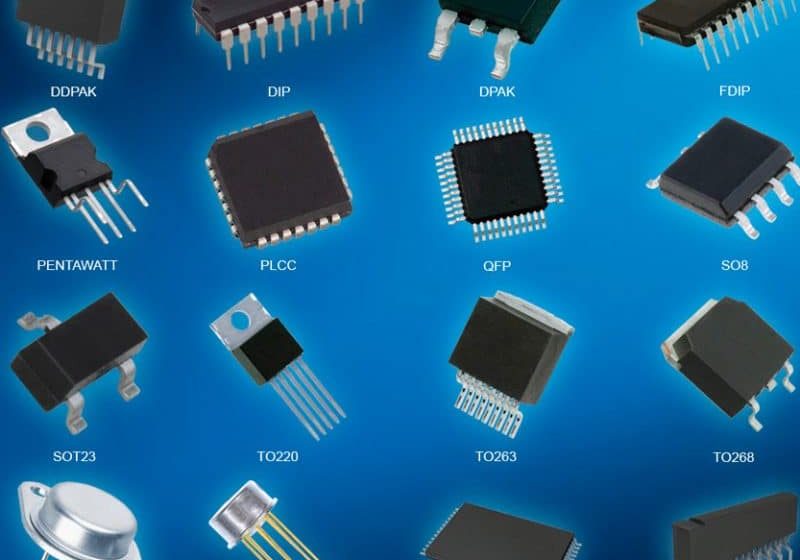

The first new requirement for all NYC elevator systems was adopted by the city council several years ago. Its purpose is to provide an upgrade to all hoist machines with single plunger brakes. This upgrade can be accomplished in one of two ways. The first way is to alter the single-plunger brake assembly to a dual-plunger type. The second (and more common) approach to compliance is to refit the hoist machine with an emergency braking system that will meet the requirements of “Unintended Car Movement Protection” as specified in ASME A17.1 Section 2.19.2. This section states that an emergency brake must be engaged should an uncontrolled motion or up overspeed event occur. This upgrade to all hoist machines must be done by 2027 as mandated by the NYC Building Code, Appendix K3, and Rule 3.8.4.1. The specified year seems a long way off, but keep in mind there are approximately 72,000 elevators in the greater metropolitan area and, when seen from a scheduling prospective, the deadline for compliance is not far off at all.

The next requirement deals with securing the car door/gate between landings to prevent passengers from self evacuating during an entrapment. This action, taken by passengers when panic sets in, has resulted in more fatalities than any elevator-system malfunction, whether electrical or mechanical. The remedy for this long-recognized passenger-safety issue is to secure the car door/gate while the elevator travels between landings, thus preventing self evacuation. While this has been a requirement for NYC elevators since 1985, its enforcement has now been extended to include all elevators, regardless of their installation date, as required under ASME A17.3. The A17.1 Handbook on Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators, 2000 Edition, Section 2.12.5, explains the rationale behind the use of door restrictors in this way:

“When a passenger elevator is outside the unlocking zone, it is unsafe for a passenger to try to exit through the elevator entrance unassisted (Note: the unlocking zone is an area seven inches above or below the landing). In fact, there have been many reports of fatalities due to this condition. A person inside the car should not be able to accomplish their own emergency evacuation through a hoistway door when the car is located outside the unlocking zone. This requirement may be met by restricting the opening of the car door or the hoistway door.”

The third requirement is new and looks to the catastrophic event that took place on December 14, 2011, in which a woman lost her life as a result of an elevator leaving the landing with its doors opened as she attempted to board. Added to the NYC Building Code with the effective date of January 1, 2015, the new rule states that all elevators under the jurisdiction of the NYC Department of Buildings must have their hall doors and car doors/gates monitored for proper operation. All passenger and freight elevators must comply by January 1, 2020, per ASME A17.3 as modified by NYC Building Code Appendix K3, Rule 3.10.12. The rule simply states that means shall be provided to monitor the hall doors and car door/gate for faulty contact circuits and, if a faulty circuit is detected, the elevator shall be prevented from operating and removed from service. The deadline for compliance, leaves four years, or 1,241 working days, to apply this safeguard to the approximately 72,000 elevators in the greater metropolitan area. Ultimately, given the small window for compliance provided by this rule, both consulting firms and elevator companies have an obligation to advise their clients as to the rule and its implications. As can be imagined, the liability exposure is huge.

The question heard most often when a code change is contemplated or adopted is, “How will the change be accomplished on the thousands of existing elevator systems?”

The final change being contemplated by the NYC Code Committee is in response to the storm flooding experienced in the downtown area several years ago as a result of Hurricane Sandy. There is a new code requirement being proposed to provide fluid detection systems for elevator pits in buildings located in areas designated as flood zones. These systems would monitor the elevator pits for liquid intrusion and relocate all elevators in an affected building to a safe landing above the base flood elevation (BFE) plain. Once relocated, the elevator systems would be removed from service. The elevators would be returned to service only when the liquid intrusion monitoring device were manually reset by trained personnel. This proposed addition to the code is being reviewed by several city agencies, including the NYC Fire Department. It is expected to be presented to the city council within the year.

It is important to note that the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) has weighed in on this issue. Protecting buildings constructed in “special flood hazard areas” from damage caused by flood forces is an important objective of the NFIP. In support of this objective, the NFIP regulations include substantial improvements to existing buildings in areas designated as flood zones. As NFIP’s “Technical Bulletin 4,” dated November 2010, states:

“All appropriate measures must be taken to mitigate flood damage to elevators and associated equipment to the maximum extent possible. Although some components must be located below the lowest floor of a building (i.e., below the BFE) to function, most elevator components vulnerable to flooding can be located above the BFE or be designed to minimize flood damage.”

The resulting compliance with the NFIP regulations should result in lower flood-insurance premiums, since the premiums are determined, in part, by the level of exposure to storm damage to which the elevator equipment is exposed. Once this comprehensive rule is adopted, it will go a long way toward protecting the riding public from possible injury or worse. The new proposed rule will also have the effect of saving the building owners the substantial cost of replacing cabs, hoist cables, electrical cables, car-operating panels and car-top equipment, all of which could be damaged if the elevator systems were left in service.

The question heard most often when a code change is contemplated or adopted is, “How will the change be accomplished on the thousands of existing elevator systems?” While the code changes are required to be implemented within a given period of time, there is no requirement to replace the existing elevator equipment to accomplish these changes. This allows the industry the opportunity to apply upgrades to existing elevator systems to accomplish the new rule requirements, thus dramatically lowering the cost of compliance by building owners as compared to a complete elevator-system replacement. The cost of these upgrades is usually one-fifth the cost of a new elevator system.

The rule of thumb for refitting existing systems with new logic functions or equipment has always been, “Is the existing elevator system operational and relatively trouble free?” If the answer to this question is “Yes,” then an upgrade to the elevator system is an avenue that should be explored. Refitting is a method that uses a device to add new functionality to existing operational elevator systems. These upgrades alter an elevator control system in a way that incorporates new logic operations to the existing controller’s operation.

An upgrade can be applied to the mechanical side of an elevator system in the form of an emergency brake added to an existing hoist machine or a door restrictor added to an existing door operator. Devices used for these upgrades must meet certain standards, the most important of which is that they are compatible with the host elevator system, while upgrading the operation to the new requirements. Without the “compatibility” factor, a refit device becomes a liability, rather than an asset. While elevator modernization has been a widely accepted practice throughout North America in recent years, it is generally not as well known a remedy for code compliance as is replacement of the entire elevator system. It has become more popular in recent years as a result of a poor economy. When a building is faced with the high cost of elevator-system replacement, refitting it with an upgrade becomes an attractive and viable option.

From NYC’s oldest elevator systems to its newest additions, the NYC Elevator Code Committee, Department of Buildings and City Council are committed to keeping its vertical transportation, which the public uses to reach the clouds, the safest conveyance they, as a team, can provide.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.