Salovaara and Peter Severin More (or Less) Elevated Fiction

Aug 1, 2013

Your author’s “Elevated Fiction” History article (ELEVATOR WORLD, June 2012), examined several detective and mystery novels that incorporated an elevator as a key plot element. This month, a different set of fictional narratives will be examined. However, the literary examples included in this month’s article are, perhaps, slightly less “elevated” than the previous examples: these stories were culled from comic books and science fiction/horror magazines of the 1950s and 1960s. While this may seem like a kind of “trip down memory lane” — before the advent of “graphic novels” – these stories do serve as yet more evidence of the cultural presence of vertical transportation.

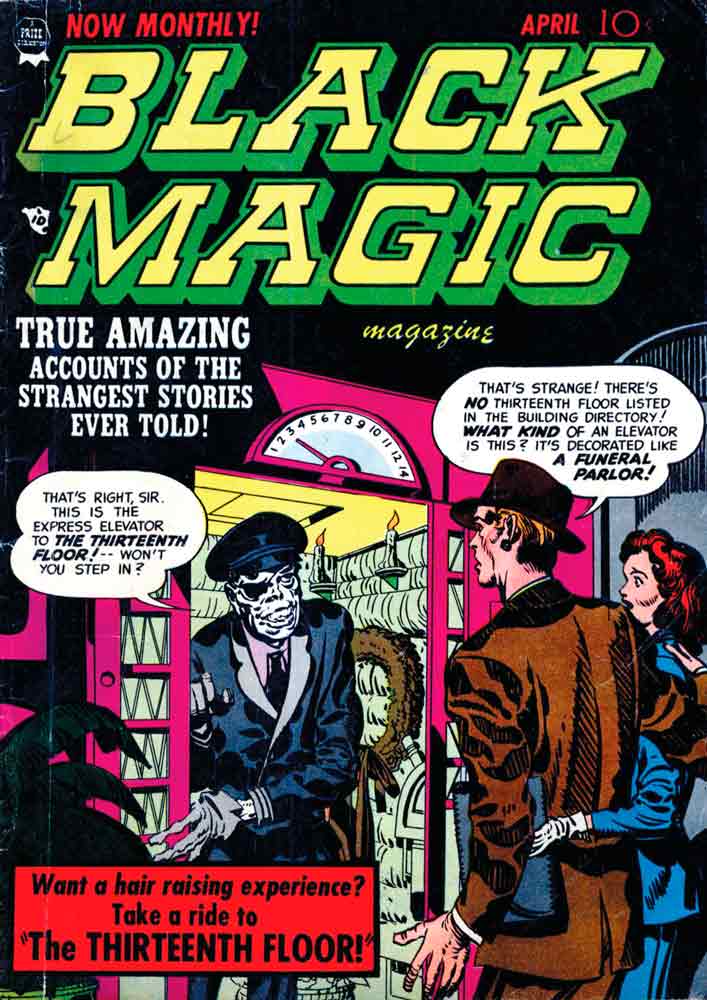

In October 1950, S&K Comics launched a new title: Black Magic. The creative team behind this effort was Jack Kirby (1917-1994) and Joseph Henry “Joe” Simon (1913-2011). This remarkable duo was responsible for an extraordinary range of comic books and comic-book heroes during their lengthy careers; they are best remembered for their creation of Captain America in 1940. The April 1952 issue of Black Magic featured Kirby’s distinctive cover art, with an open elevator car through which the operator beckons a waiting couple to enter (Figure 1). The car is decorated to resemble a funeral parlor and features fabric-draped walls, candles and a wreath. However, the car also includes a typical controller (seen to the right of the operator), typical center-opening doors and a typical hallway floor indicator (missing the number 13).

The cover highlights a story titled “The Thirteenth Floor” and implies its plot includes a harrowing elevator ride. Of course, the use of a building’s 13th floor as a site of mysterious events derives from the urban legend that tall-building owners typically avoided labeling a floor with the number 13 because of its association with bad luck. Some readers may have been slightly disappointed when they reached this particular story, the third of five included in the issue. The elevator was not the primary setting for the story, nor did it convey passengers to the mysterious 13th floor. Instead, it served as a means of escape and resembled a normative elevator car.

The story concerns Clement Dorn, a man considering suicide. Seeking a quiet place where he can “leap to his death,” he ascends the stairs from the 12th to the 13th floor, where he finds a court-like proceeding in progress. He quickly ascertains that the proceeding decides which “new arrivals” are dispatched to heaven and which are sent to hell. Once it is determined he is not really “dead,” Dorn is allowed to leave via a door labeled “42.” After passing through the door, he “plunges” down a “thousand foot drop into a well of darkness” (Figure 2). When he opens his eyes, Dorn finds himself sitting on the floor of a typical elevator car with a uniformed operator offering him assistance; he leaves the elevator with a new perspective on life, and the story concludes.

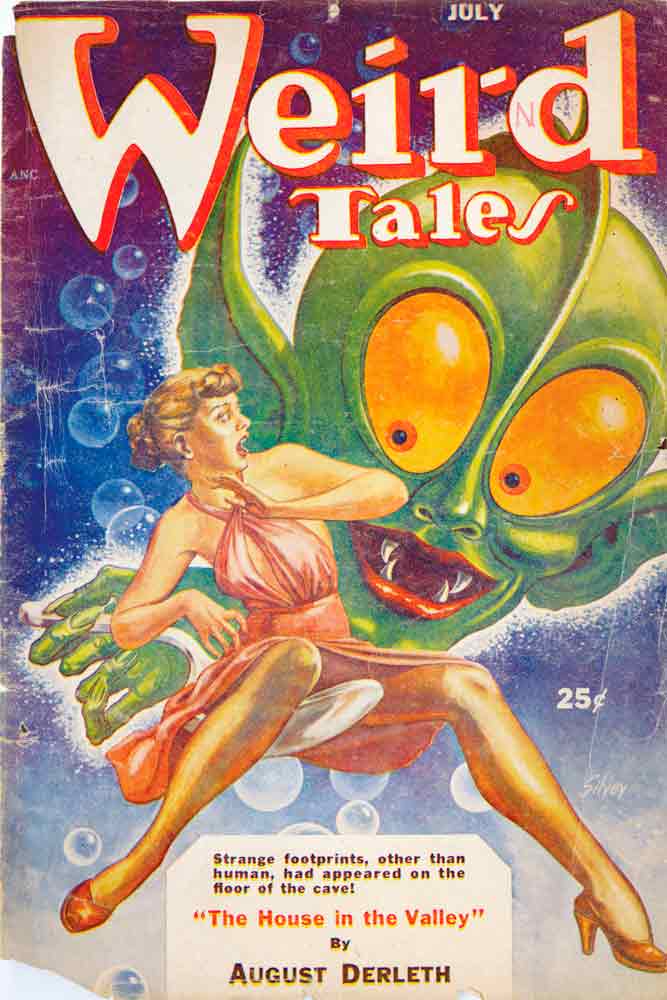

In the horror story “On the Elevator” by Joseph Payne Brennan (1918-1990), published in the July 1953 issue of Weird Tales, the elevator serves as a primary plot device (Figure 3). The setting is an old seaside hotel during a fierce nighttime storm. The night-desk clerk observes a mysterious figure clad in a long, dark raincoat enter the lobby, call the elevator, go into the car and ride up. Not long afterward, a “decidedly hysterical” woman calls the front desk and describes having just seen “something on the elevator which had imbued her with pure terror.” The desk clerk presses the elevator call button and quickly determines by the motionless cables – glimpsed through a window in the shaft door — that the elevator is not moving. He surmises something must be blocking the door on the floor where the car has stopped. Fortunately, the female guest is staying on the third floor, and he quickly climbs the stairs to investigate. When he arrives, he finds that the elevator has moved to an upper floor. At this point, he hears a loud scream and sees “a blur of movement in the shaft as the elevator shoots past.” After calling the police, he and two officers descend into the basement, where they discover the mangled corpse of a hotel guest, an empty and rotting raincoat lying half in and half out of the car, and wet footprints leading away from the elevator and out into the storm. While the story is, in many ways, decidedly average, its author was not. Brennan was an award-winning writer of horror/fantasy stories and was equally well known as a poet. It is interesting that Brennan decided to omit the elevator operator as a character. Although the story takes place at 11 p.m., most large hotels employed night elevator operators who also served as additional security, and monitored and assisted guests as they arrived and departed.

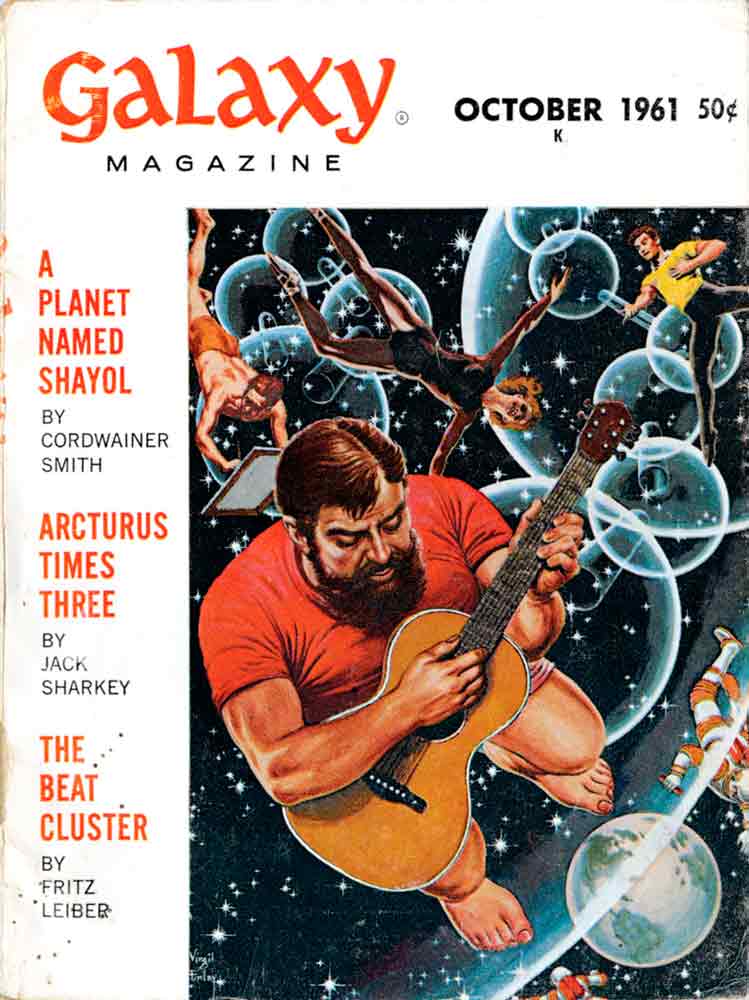

The October 1961 issue of Galaxy Magazine included a “novelette” titled “The Spy in the Elevator,” written by Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008) (Figure 4). Westlake was an incredibly prolific and successful author: during his career, he wrote more than 100 books, an equal number of short stories and five screenplays, one of which (The Grifters) was nominated for an Academy Award. His story is the best of the four reviewed for this article. It is set in the early years of the 21st century following a global nuclear conflict. As a result of the conflict and subsequent contamination of the environment, people are forced to live in massive, isolated “projects,” which are described as 200-story, self-sustaining buildings. The plot centers on what happens when the main character, who lives on the 153rd floor, attempts to visit his girlfriend, who lives on the 140th. When he presses the hallway call button, he is shocked when the elevator doesn’t arrive:

“The elevator had always arrived before, within thirty seconds of the button being pushed. This was a local stop, with an elevator that traveled between the hundred thirty-third floor and the hundred sixty-seventh floor, where it was possible to make connections for either the next local or for the express. So it couldn’t be more than twenty stories away. And this was a non-rush hour.”

This description of the building’s elevator service is normative in the expectation that the elevator should arrive within 30 seconds. It is somewhat surprising, however, in its account of the operation of a local elevator, which stops at a floor that operated as a type of sky lobby. The latter is surprising, because Westlake wrote this story four years before construction began on the John Hancock Center in Chicago, the first tall building that employed the sky-lobby system.

The reason the main character cannot call the local elevator to his floor is that access to all of the building’s elevators has been restricted, because the authorities are chasing a spy from another project who has taken refuge in one of the elevators. The authorities are unable to capture the spy, because, as the main character is informed:

“He plugged in the manual controls. We can’t control the elevator from outside at all. And when anyone tries to get into the shaft, he aims the elevator at them. . . . He runs it up and down the shaft. . . trying to crush anyone who goes after him.”

This presents an intriguing connection between the new world of the operator-less elevator, which was approximately 10 years old when this story was written, and the older generation of operator-driven machines. The idea that someone could “plug in” a manual control system that overrides the existing

system is also a fitting aspect of a science-fiction story. The story concludes when the spy escapes the elevator via an emergency shaft-

access door (located in the building’s stairwell), and the main character captures him.

The final story examined for this month’s article is titled “Mystery of the 13th Floor” and returns to the theme found in Black Magic, where the 13th floor is the site of mysterious events. It appeared as an un-illustrated, one-page story in the November 1967 issue of Mandrake the Magician (Figure 5). However, unlike the first story, the elevator now serves as a primary plot device. The main character is identified as George Wilson, who is late for an appointment and becomes increasingly agitated as the crowded elevator slowly climbs toward his destination. After the last passenger exits at the 12th floor and Wilson thinks he is speeding on his way at last, the elevator lights go out and the car stops. He finds that nothing works, not even the emergency call button. After waiting to be rescued, Wilson decides to take a chance and climb out the escape hatch:

“With little effort he managed to push the hatch open and pulled himself through it. He was now standing on top of the elevator car. In the darkness he could feel the rush of wind down the shaft which reached sixty stories above him. . . . Again, he used the lighter and saw that the door to the elevator on the floor above him was slightly open. . . . He reached up and grasped the ledge above him and pulled himself up. . . . Finally he crawled out of the elevator to the safety of the next floor.”

The “next floor” was, of course, the 13th, where Wilson discovers a meeting in progress:

“Ah, Mr. Wilson,” said the man in soft tones, “you’re just in time for the reading of the will.”

“Whose will?” he asked.

“Yours!” was the reply.

The story concludes the next morning when, after the building’s power is restored, the elevator returns to the ground floor, the doors open and Wilson’s body is discovered.

While these stories cannot be classified as “great” literature, the presence of elevators in comic books and science-fiction/horror magazines and their use as critical plot instruments of terror or suspense is not surprising. As EW readers know and previous history articles have shown, elevators have maintained a consistent cultural presence since their invention and have been featured in movies, children’s books, mystery novels, popular music, etc. As EW readers spot these popular-culture references, they are encouraged to share them with your humble author and elevator historian.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.