Talking Elevators

Oct 1, 2012

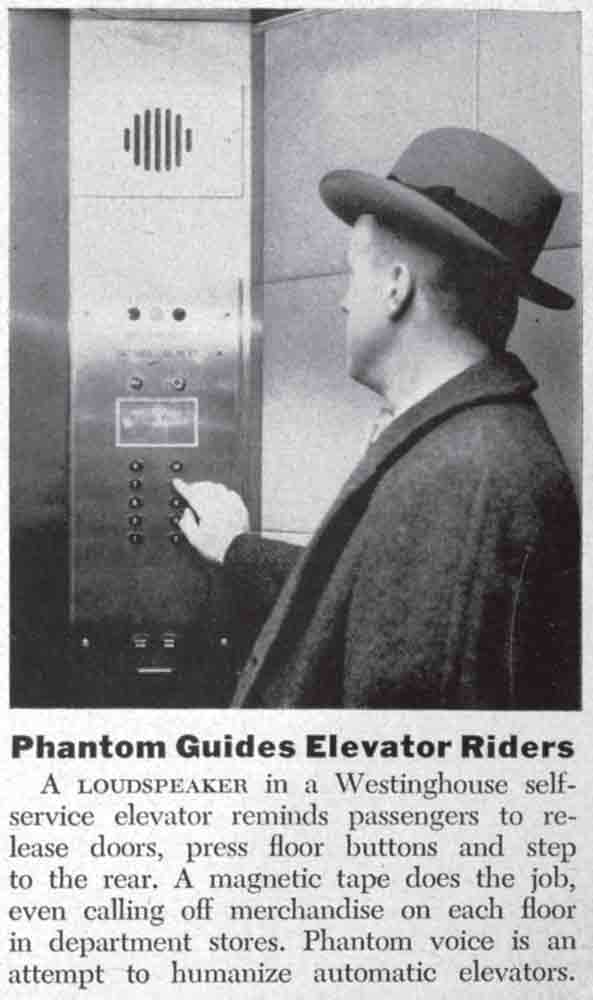

The public’s response to talking-elevator systems developed by Westinghouse and Otis during the 1950s

The introduction of “operatorless” elevators in the 1950s fundamentally changed the experience of riding an elevator: passengers were no longer passive participants who simply watched the operator “drive” the car; they now played an active role in the machine’s operation. However, as recounted in a previous article (“No Operator Needed,” ELEVATOR WORLD, November 2003), many passengers struggled as they attempted to make the transition from a passive to an active rider. A feature specifically developed to aid in this transition was the automated audio-messaging system, which transformed operatorless machines into “talking elevators.” This article will briefly explore the talking-elevator systems developed by Westinghouse and Otis, and the public’s reception of this innovation as found in the technical and popular press.

In the summer of 1954, Westinghouse debuted its new “Phantom Voice” system in the recently completed National Distillers Building in New York City. The building featured 10 fully automatic elevators, one of which was a talking elevator. The New Yorker magazine, reporting with its typical flair, described the experience of riding the elevator as follows:

“The doors slid open without a word, disclosing a cab with rich-looking brown walls and a mouse colored carpet. We hesitated before entering, and the elevator uttered an irritated buzzing sound. No sooner had we stepped inside than the elevator said, ‘Press your floor button, please!’ Before we could choose a likely button, the elevator repeated its request, this time with a hint of well-bred impatience in its well-bred voice. Hastily we pushed ‘14,’ the highest number on the panel. The doors closed smoothly and the elevator started up. At the eighth floor, it stopped, opened its doors, and said sharply, ‘Going up!’ A man got in and pressed the ‘13’ button. We shot up in silence to the 13th floor, where the man got off. On reaching the 14th floor, the elevator stopped and opened its doors, but we stayed aboard. ‘Going down!’ said the elevator, and we seized that moment to test its response to an unexpected delay. We laid a hand against the rubber edge of one of the doors as it started to close. ‘Release the door, please!’ the elevator said, in such a commanding tone that we did so at once, and the doors slid shut. Having pushed the ‘1’ button, we started down, and at the halfway mark we decided to see what sort of conversation the red emergency button on the panel would provoke. We pressed the button, and the elevator stopped and said, ‘The car has been stopped because the red emergency button has been pressed. If emergency has passed, pull the button out.’ Humbly, we pulled the button out.”

The magazine also reported that if the car stopped “due to a mechanical failure,” the voice would announce: “An automatic protective device has stopped the car. Please press the alarm bell to notify the engineer.” Although it is doubtful the Phantom Voice actually conveyed the suggested “hint of well-bred impatience” or the emphatic tone described by The New Yorker, there is little doubt that riding a talking elevator was perceived as a novel experience.

However, this novelty was also described as a temporary phenomenon, not because it was assumed that passengers would grow accustomed to this experience, but because it was, according to The New Yorker, a “temporary little wonder. . . . It has been devised to help gain a greater acceptance for self-service elevators, which manufacturers have now brought to a pitch of more than human adroitness but which the public remains leery of.” In fact, the public’s slow, almost hesitant acceptance of automatic elevators was reinforced by the observation that:

“Although most of the elevators being installed in our big new office and apartment buildings are designed to be automatic, they will be run by operators until the owners of the buildings are convinced that the tenants have become brave enough to do their own button pushing; when that day arrives, operators will be dispensed with and talking elevators will be made to shut up.”

In the interim, The New Yorker noted that “everything else being equal, we’d prefer a silent elevator to a talking one, but if the choice lies between an elevator that talks and an elevator operator that talks, we’ll take the former every time.” The rationale behind this choice was simple: “The talking elevator is self-service, and its hollow, tape-recorded voice is limited to a few pertinent remarks; there’s no chance of it stopping to relay the latest joke or peddle sweepstakes tickets.”

While The New Yorker provided one of the most thorough accounts of riding a Phantom Voice-equipped elevator, it is only one of a diverse set of magazines and journals that covered this story, a set which included Automatic Control, Control Engineering, Engineering News-Record, Science Digest, Popular Science, National Safety News, Finance and Data Systems Engineering. One of the intriguing aspects of this collection of articles is that their authors reported slightly different versions of the recorded messages given to passengers. In contrast to the curt commands recounted by The New Yorker, an article in Popular Science, which described all aspects of the fully automatic elevator in reference to its electronic “brain,” stated:

“If you forget to push your floor button the brain waits a polite interval. Then a ‘phantom voice’ reminds you. A message comes through the speaker in the car: ‘This is an automatic elevator, push your floor button please.’”

Popular Science also reported other Phantom Voice messages as: “This car up,” “This car down,” “Stand back from the door. You are delaying the car” and “If you pushed the emergency button by mistake pull it out again. If not, you may talk to an engineer through the car speaker.” In 1960, Fred A. Annett (1879-1959), in the third and final edition of his important reference book Elevators: Electric and Electrohydraulic Elevators, Escalators, Moving Sidewalks, and Ramps noted most Phantom Voice systems consisted of a set of six messages, which included “Please press your floor button,” “Please release the doors” and “Be calm; a protective device is now in operation.”

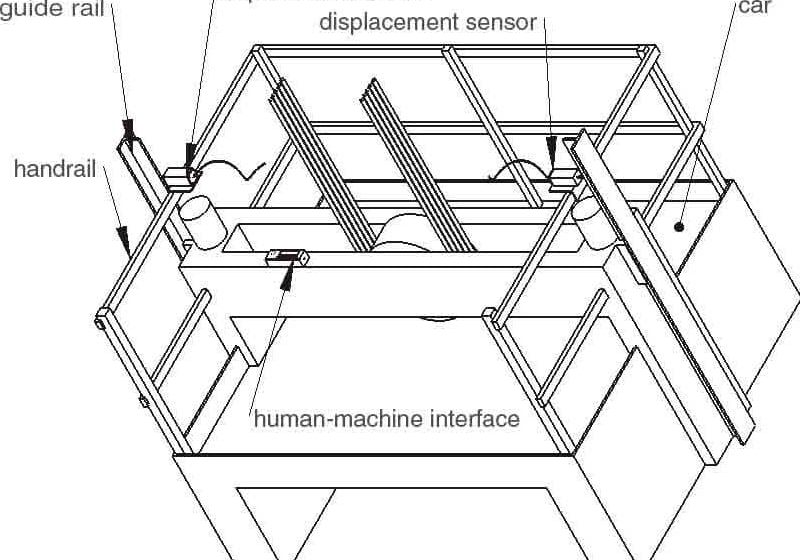

The subtle variations in message content cited above may have resulted from careless note-taking on the part of the authors or Westinghouse’s experiments with different messages to gauge their effectiveness. In fact, the operational characteristics of this system appear to have made it relatively simple to change messages. In June 1955, EW described the system as a “magnetic tape device” with the “tape playback machine installed in the elevator machine room and connected by cables to loud speakers concealed in each car.” According to Annett, the Phantom Voice system consisted of a series of individual “tape recordings” that, when activated, traveled “past a single-channel magnetic head.” The magnetic head relayed the message “through the elevator’s control cables to a loudspeaker in the car.”

Also in June 1955, approximately one year after the debut of Westinghouse’s Phantom Voice system, Otis introduced “Elevoice” at the Building Owners & Managers Association convention in Cincinnati. The account published in Engineering News-Record echoed the Phantom Voice articles in describing the new system as a “device designed to eliminate confusion for passengers in the transition from attendant operated to automatic elevators.” Engineering News-Record also provided a brief technical description that highlighted the operational differences between the two systems. The Elevoice system employed “loud speakers” that were:

“. . . connected to one or more master drums on which any number of messages are electronically recorded. The drums, which are usually located in the machinery room, rotate every three seconds and deliver a message appropriate to each car’s movement.”

This description matched that found in the system’s primary patent (application filed by Lew H. Diamond, John H. McConnell, Murray Hill and Henry B. Brown on March 28, 1956, and awarded July 4, 1961) Elevator Announcing System, U.S. Patent No. 2,991,448:

“A variety of messages. . . are prerecorded on a magnetic sleeve in such a manner that there is a separate track. . . for each message. The magnetic sleeve is fixed onto a drum which is rotatable at a constant speed. . . and the time required for one revolution. . . corresponds to the duration of a typical message.”

The advertised features of Otis’ Elevoice system were, not surprisingly, similar to those of Westinghouse’s Phantom Voice:

“The voice will announce the floor at which the car has stopped regardless of the number of floors between stops or the direction of travel. It will caution against delaying the operation of the door, but only when the operation is being delayed. Too, it will suggest that entering passengers press buttons for the floors they want and step back in the car.”

However, Otis also suggested its system was flexible, easy to change and adaptable to diverse settings:

“In department stores, the voice can announce the merchandise on sale at each floor, with daily changes. In office buildings, it can call out tenants’ names. The voice can be that of a Bostonian, Atlantan, Chicagoan, or the dulcet tones of a well-known movie actress.”

Unfortunately, the process by which such “daily” changes could be made is unclear. Otis’ advertising claims also raise another interesting question – if it were possible to utilize the “dulcet tones of a well-known movie actress,” who was under contract to lend her voice to a talking elevator? A similar question may be asked of the Phantom Voice – in response to an inquiry from The New Yorker, Westinghouse simply replied that the voice used was that of an “N.B.C. announcer.”

The New Yorker article also prompted a reader to write a letter to the editor that reveals another talking-elevator mystery. The author claimed there had been talking elevators in England “for years,” which were located:

“. . . in the underground railway’s Goodge Street Station. . . . Actually, there are two talking lifts at Goodge Street, one beside the other. The Goodge Street lifts are not as advanced in their speech as the one in the National Distillers Building; they have only five words apiece, but they do rather well with those. The procedure is as follows: On arriving at Goodge Street, you give up your ticket to the ticket collector (live, male) and step into one of the two lifts, which are small and lined with theatrical advertisements in neat glass frames. Ahead of you is a closed door and behind you an open one. Presently, signs over both doors light up. I forget the exact wording, but it is something like, ‘WARNING: GATES CLOSING.’ This is followed by the sharp ringing of a bell, and then the lift says very loudly, ‘Stand clear,’ waits for the passengers to jump, and adds, in a much smaller voice ‘of the gates.’ The open gate then slams to with a crash, and you are borne aloft and jettisoned at street level without further comment from anyone.”

If any of EW’s British readers can shed light on these elevators, please feel free to contact your author or the EW Editorial Department at e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected], respectively. Similarly, if any reader would like to share information on the operation of the Phantom Voice or Elevoice systems, please contact us.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.