Explaining the focus and construction of the important American standard between its inception in 1921 and 1931

The first three editions of the American Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators employed the same organizational scheme: one or more introductory sections followed by a section titled “Definitions” followed by the code’s core content, expressed as a series of “rules” organized into seven “parts.” The introductory sections explained the code’s purpose and provided general guidance on its use. These sections increased in content and complexity with each subsequent edition. The definitions section also steadily increased in size, growing from 40 terms in 1921 to 82 terms in 1931. And, although the text of some of the rules was modified from edition to edition, its overall focus remained largely unchanged in these early code editions. However, these rules cannot be understood without first understanding the editorial development of the introductory and definitions sections.

First Edition

The first edition, A Code of Safety Standards for the Construction, Operation and Maintenance of Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators: 1921 provided a minimal introduction, which was simply titled “Application of the Code.” This was divided into three paragraphs (each identified by a lowercase letter) and included one note:

“a. This code of safety standards is intended as a guide for the construction, maintenance and operation of elevators, dumbwaiters, escalators and their hoistways except as stated in the following paragraph.

“b. This code does not apply to belt, bucket, scoop, roller or similar inclined or vertical freight conveyors, tiering or piling machines, skip hoists, wharf ramps or apparatus in kindred classes, amusement devices, stage lifts or lift bridges, elevators of capacity exceeding 30,000 pounds and platform area exceeding 300 square feet when suspended by cables near each corner of the hoistway and at additional positions, nor to elevators used only for handling building materials and mechanics during the building construction.

“NOTE: The types of apparatus listed above should be made subject to suitable specifications for each type.

“c. The code recognizes the deteriorating influence of wear, rough usage, and the atmospheric conditions under which elevator apparatus, particularly door locks, interlocks and electric contacts, are required to operate. In the design and installation of such apparatus, due regard must be given to these conditions and to the construction upon which such apparatus is mounted.”

This series of statements reflects, perhaps, the relative newness of the idea of a national code: it was intended as a guide, rather than a set of prescriptive rules, it had a specific application, and it recognized the realities of elevator usage. It is also important to note that these statements did not, in fact, provide any guidance on the actual application or use of the code.

Second Edition

The second edition, Engineering and Industrial Safety Standards: A Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators: Rules for Construction, Inspection, Maintenance and Operation: 1925, included an introduction and a section titled “Scope and Purpose.” The introduction offered a more fulsome description of the code’s proposed application:

“This Code is intended as a guide to state and municipal authorities and may be adopted by them in whole or in part. It is also intended for use as a standard reference for safety requirements for the use of elevator manufacturers, architects, and consulting engineers. For this purpose it may be used to advantage in connection with the Standards for Elevator Construction now in preparation under the American Engineering Standards Committee procedure. It is also intended as a standard for use by hotels, department stores, office buildings and other users of elevators through voluntary application.”

The “Scope and Purpose” section began with a revised version of the first edition’s three-paragraph introduction. The opening sentence, now labeled “Scope,” read as follows: “This Code of safety standards covers the construction, inspection, maintenance, and operation of elevators, dumbwaiters, escalators, and their hoistways except as stated in the following paragraph.” (The paragraph on elevator types not covered by the code remained the same.) An additional subsection titled “Purpose, Interpretation and Exceptions” expanded the introduction’s explanation of the code’s proposed application and use:

“The purpose of this Code is to provide reasonable safety for life and limb. In case of practical difficulty or unnecessary hardship the enforcing authority may grant exceptions from the literal requirements or permit the use of other devices or methods, but only when it is clearly evident that reasonable safety is thereby secured. Note: It is suggested that in cases where exceptions are asked for, the enforcing authority consult with the Committee on Elevator Safety Code, care of American Engineering Standards Committee.”

Although these statements retained the use of the term “guide,” they also added the concept of inspection and provided recommendations regarding the code’s use by municipal and state authorities, architects, engineers and the elevator industry. The description of the process for requesting “exceptions” appears to somewhat contradict the idea that the code “may be adopted. . . in whole or in part” and, perhaps, expressed the authors’ desire for stricter implementation and interpretation of the code’s contents. The reference to the development of a parallel document – “Standards for Elevator Construction” – is also intriguing. However, thus far, these standards have not been found (although the search continues, and they may be the topic of a future article).

Third Edition

The third edition of the code, American Standard Safety Code for Elevators, Dumbwaiters and Escalators: Rules for Construction, Inspection, Maintenance and Operation: 1931, included a forward and an introduction, the latter of which was divided into two sections: “General” and “Scope and Purpose.” These sections contained much of the same text found in the second edition with a few editorial modifications and additions that responded to the ongoing implementation of the code. This was reflected in the forward, which noted:

“The application of this Code in the formulation of various state and municipal codes emphasized the need for its further development and extension. Accordingly, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers requested the American Standards Association to authorize the organization of a Sectional Committee to undertake this revision.”

While this serves as a general indication of the code’s usage, it raises questions regarding the degree to which, by the late 1920s, the code had been adopted and/or used to formulate local and state elevator codes. This aspect of its use was also reinforced by a subtle shift in language. The sentence “This Code is intended as a guide to state and municipal authorities and may be adopted by them in whole or in part” was revised to read, “It is intended as a guide to state and municipal authorities in the drafting of their regulations and may be adopted by them in whole or in part.” This statement was followed by specific advice on the development of new codes:

“It is suggested that before adopting this Code for state or municipal use or drafting a code with this as a basis, a careful survey be made of the state or municipal regulations providing for prior publication, public hearings, or similar means of bringing such regulations before the public. Whether required by law or not, public hearings are beneficial in that they permit building owners to voice their objections to particular rules and at the same time provide an opportunity for the authorities to explain the reasons for such rules, and the public is thus informed of the need for such regulations.”

Definitions

This new language, and the growth in the information found in the code’s introductory sections from 1921 to 1931, represents the gradual maturation of the presence and implementation of national codes and standards. This process also influenced the growth of the “Definitions” section over this same period. The first edition introduced a list of 40 terms prefaced by a simple declaration: “In this code the meaning of the following terms shall be understood to be as here defined.”

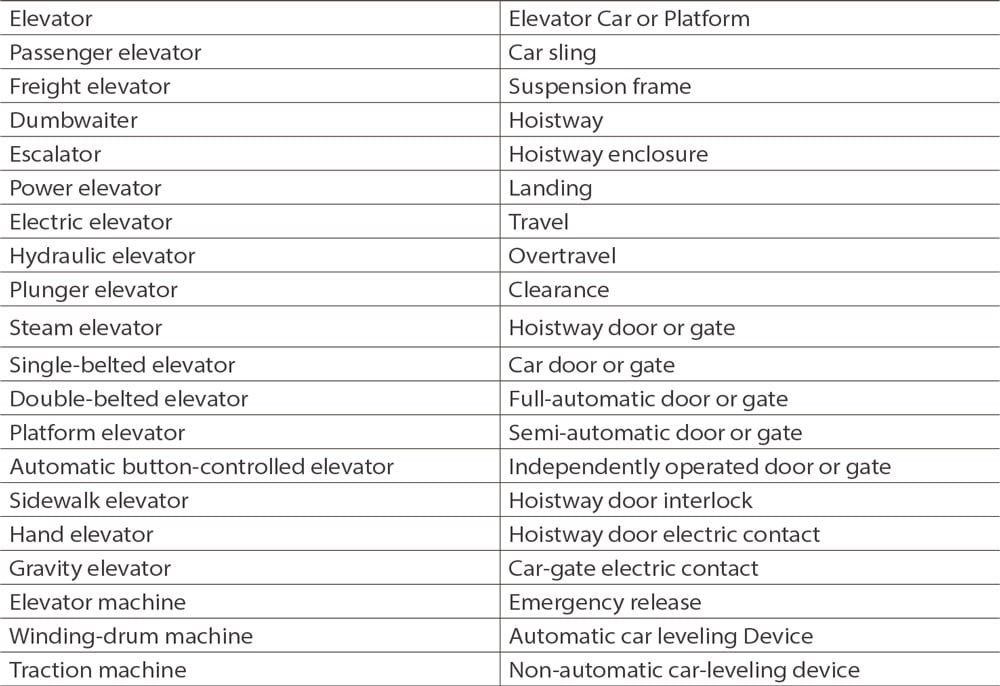

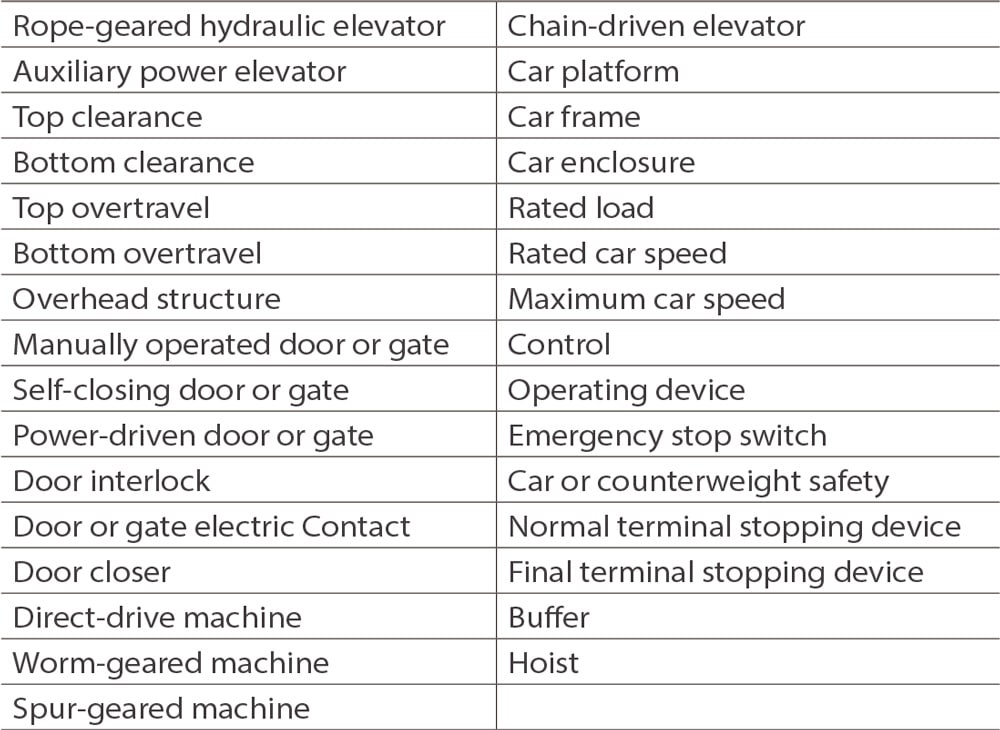

Although the included terms comprised a kind of dictionary, they were not listed in alphabetical order, a fact that made it difficult to “lookup” a given term. However, the terms were grouped or organized loosely by topic, such as elevator type, machine type, cars, hoistways, doors/gates and miscellaneous (Table 1). In the second edition, in addition to editorial changes to several definitions, three terms were eliminated (“car sling,” “non-automatic leveling device” and “suspension frame”), two terms were divided into separate terms (“clearance” became “top clearance” and “bottom clearance,” and “overtravel” became “top overtravel” and “bottom overtravel”), three terms were modified or contracted (“car-gate electric contact” and “hoistway door electric contact” became “door or gate electric contact,” and “Hoistway Door Interlock” became “Door Interlock”) and 25 new terms were added, bringing the total to 62 (Table 2). The new terms primarily addressed cars and gates.

The definitions section of the third edition reflected the ongoing development of the code (the number of terms increased from 62 to 82), as well as the dynamic nature of code writing. The latter was evidenced by the reversal of several editorial decisions made in the second edition: “door interlock” was changed to “hoistway-door interlock” (the term used in the first edition), and “door or gate electric contact” was once again divided into two terms: “car-door or gate electric contact” and “hoistway-door or gate electric contact” (similar terms were used in the first edition). Other modifications included changing “power-driven door or gate” to “power-operated door or gate,” changing “automatic-control elevator” to “automatic operation,” deleting four terms (“semi-automatic door or gate,” “rated load,” “rated speed” and “maximum car speed”) and adding 22 new terms (Table 3).

The editorial process may also be illustrated by an examination of three terms: “elevator,” “passenger elevator” and “hoistway door interlock.” The definition of “elevator” (“an elevator is a hoisting and lowering mechanism equipped with a car or platform which moves in guides in a substantially vertical direction”) remained the same in each of the first three code editions. The term “passenger elevator” underwent modest editorial changes:

- 1921: “A passenger elevator is an elevator on which passengers, including employees other than those specified in the definition of freight elevator, are permitted to ride.”

- 1925: “A passenger elevator is an elevator that is designed to carry persons to its rated capacity.”

- 1931: “A passenger elevator is an elevator that is designed to carry persons to its contract capacity.”

The first revision simplified the definition, whereas the second – changing “rated capacity” to “contract capacity” – represented an attempt to clarify the code’s intentions. The term “rated load” had been defined as “the load in pounds which the elevator is designed and installed to carry in accordance with this code.” This term was deleted and replaced in the third edition by “contract load,” which was defined as “the load specified in the contract for the purchase of the elevator, or in the application for permit.”

The changes to the definition of “hoistway door interlock” included the modifications noted above, in addition to other changes in the text:

- 1921: “A hoistway door interlock is a device the purpose of which is: First, to prevent the movement of the car: a. Unless only that hoistway door, opposite which the car is standing, is closed and locked (Door Unit System); or b. Unless all hoistway doors are closed and locked (Hoistway Unit System); and Second, to prevent the opening of a hoistway door from the landing side: a. Unless the car is standing at rest at that landing; or b. Unless the car is coasting past the landing with its car control mechanism in the STOP position. A hoistway door or gate shall be considered closed and locked when within four (4) inches of full closure, if at this position and any other up to full closure the door or gate cannot be opened from the landing side more than four (4) inches. Interlocks may permit the starting of the elevator when the door is within four (4) inches or less of full closure, provided that the door can again be opened up to four (4) inches from full closure from any position within this range except that of full closure. (Note: The interlock shall not prevent the movement of the car when the emergency release hereinafter described is in temporary use or when the car is being moved by a car-leveling device.)”

- 1925: “A door interlock is a device, the purpose of which is: First: To prevent the operation of the elevator machine in a direction to move the car away from the landing, a. Unless the hoistway door at which the car is standing is closed and locked (Door Unit System), or b. Unless all hoistway doors are closed and locked (Hoistway Unit System); and Second: To prevent the opening of a hoistway door from the landing side, except by a key or special mechanism, a. Unless the car is standing at rest at the landing, or b. Unless the car is coasting past the landing with its operating device in the STOP position. (Note: The interlock shall not prevent the movement of the car when the emergency release hereinafter described is in temporary use or when the car is being moved by a car-leveling device.)”

- 1931: “A hoistway door interlock is a device, the purpose of which is: First: To prevent the operation of the elevator machine in a direction to move the car away from a landing unless the hoistway door at that landing at which the car is stopping or is at rest is locked in the closed position. Second: To prevent the opening of the hoistway door from the landing side, except by a special key; unless the car is at rest at the landing or, is coasting through the landing zone with its operating device in the stop position. Door unit system is an interlock system which meets the requirements of the interlock definition above, but does not require all the hoistway doors to be locked in the closed position. Hoistway unit system is an interlock system which, in addition to fulfilling the requirements given under the definition of interlock, will also prevent the operation of the car unless all hoistway doors are locked in the closed position.” (Note: The “closed position” for landing doors and gates for various types of elevators is specified under Rules 121c, 121d, and 121e.)

These changes appear to illustrate an editorial process that sought increased clarity and avoided unnecessary information.

The new terms found in the third edition primarily addressed doors, gates and operating systems. The latter serve as a reminder of the rapid development of the electric elevator in the 1920s and the invention of a variety of new push-button operating systems. The third edition also included the following introduction to the “Definition” section:

“Many of the definitions given are not used in the Code but have been included for the convenience of architects, engineers, and building owners and it is hoped that in this way a certain amount of standardization of the nomenclature of the various systems of control and operation will be accomplished.”

This statement expanded the proposed use of the code from regulatory to educational and reinforced the proposed goal of standardization across the vertical-transportation industry. These goals are also reflected in the rules that comprise the heart of the American Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators. These rules are the subject of the third and final article in this series.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.