The American VT Industry in the 1880s (Part 2)

Feb 1, 2025

An in-depth look at a Louisville, Kentucky, manufacturer

Part one of this article provided a broad overview of the American vertical-transportation (VT) industry in the mid-1880s. This overview illustrated the presence of a diverse, mature industry composed of more than 100 companies — distributed across much of the country — which offered consumers a wide variety of products. Somewhat surprisingly, this survey also revealed the almost total absence of VT companies in the Southern U.S. (the South’s sole representative was Louisville, Kentucky). If this record is correct, and the South truly lacked VT manufacturers, this fact raises important questions about who supplied the South with elevators during this period. One answer to this question is, perhaps, obvious: By the mid-1880s, Otis had established a nationwide operation that included regional offices that facilitated ordering and shipping elevators throughout most of the U.S. — a commercial practice that included the American South. However, while Otis was a leading player in the American VT industry, it was not the only source of VT products for the South (or, for that matter, the rest of the country).

Unfortunately, the character of the historical record for this period presents several challenges to determining the commercial presence and impact of many VT companies. Almost all advertisements in the 1880s encouraged prospective customers to send for a “circular” that included product details, prices, ordering information and references. The latter was a list of clients that prospective customers could visit to see a company’s elevators “in action.” These lists were often quite extensive and, when found, provide an important guide to the commercial impact of a given company. Regrettably, very few of these circulars have survived. However, on rare occasions, a company would include a reference list in an advertisement. The survival of one such advertisement, for George Scott of Louisville, Kentucky, answers, in part, the question of who, in addition to Otis, provided the South with VT systems. An investigation into the history of this company also provides insights into typical business practices during this period.

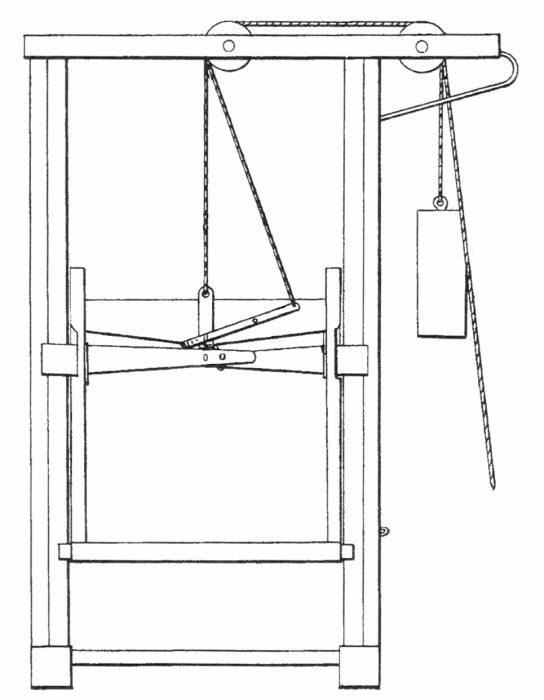

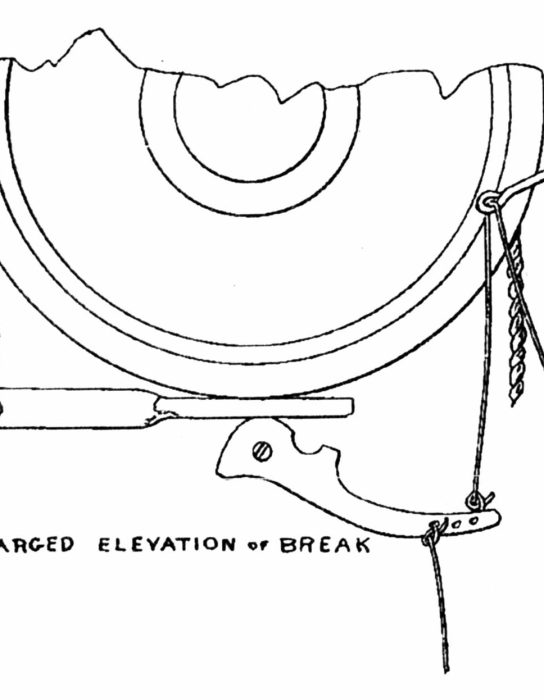

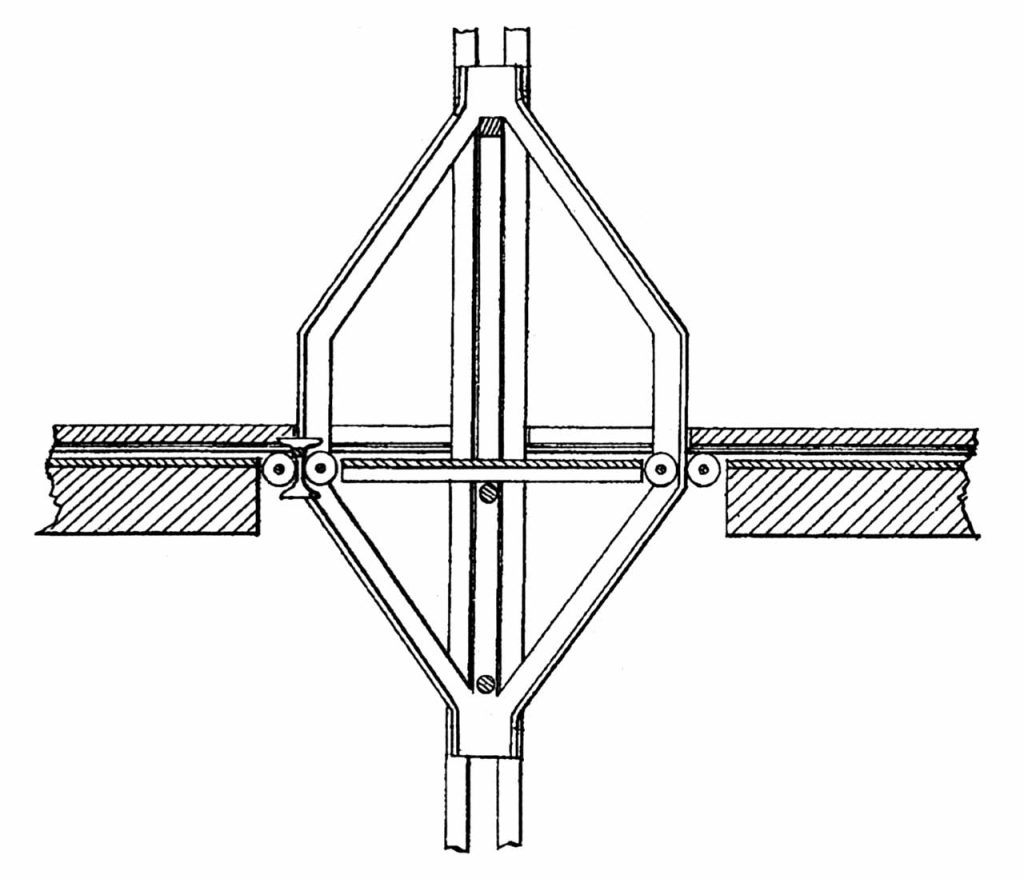

George Scott (1823-1892) was born in New Brunswick, Canada. The year he immigrated to the U.S. is unknown; however, the 1850 U.S. Census listed him as living in Louisville, working as a blacksmith. By the 1860s, he had established himself as a builder of “pumps, blocks, tackle, etc.”[1] His success in manufacturing blocks and tackles may have led him to pursue building hand-powered, platform freight elevators. Evidence of this new pursuit is found in two patents awarded to Scott in the late 1860s: Improvement in Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 81,299 (August 18, 1868) and Improved Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 91,775 (June 22, 1869). The first patent concerned an improved sheave and counterweight design for a hand-powered freight elevator; the second patent concerned an improved safety device designed to prevent the platform from falling if the hoisting rope broke (Figures 1 and 2). The primary patent drawing for the safety device leaves a lot to the viewer’s imagination regarding its design. Its operation was predicated on the well-known principle of employing ratchets (referred to as “cleats” by Scott) on the guide posts, which would be “grabbed” by a “safety clamp” if the hoisting rope broke. While the drawings for the improved sheave and counterweight design were more convincing, the patent’s overall strength was somewhat diminished by what might be termed an “unforced error” in the caption for a detail of the brake design. The caption read: “Enlarged Elevation of Break” (Figure 3).

Scott nonetheless effectively used his patents to launch his elevator business. Ironically, the level of his success was indicated by two events that occurred in 1871 which, while signaling the public’s and VT industry’s notice of his efforts, where doubtless unwelcomed by Scott. On January 10, 1871, Henry J. Reedy of Cincinnati filed a lawsuit claiming that Scott had infringed on his patent, Improvement in Hoisting Machines, U.S. Patent No. 78,829 (June 9, 1868), by building and selling “a number of machines — the exact number unknown — which in principle and mode of operation were the same as those described” in Reedy’s patent.[2] As the suit continued, it was expanded by Reedy to include Scott’s 1868 patent. However, when the suit was finally concluded in 1874, Scott was found not to have infringed upon Reedy’s patent — a decision that was first reached in an arbitration settlement in 1871. The second event that highlighted the public’s awareness of his company was even less welcome than Reedy’s lawsuit. The August 4, 1871, edition of the Louisville Courier-Journal included an account of a fire that was described as “one of the most destructive that has visited Louisville in a long time.”[3] The buildings destroyed included “George Scott’s elevator shop,” which was valued at US$3,000 (and which was uninsured).[3]

Scott quickly rebuilt his “elevator shop” and, by the mid-1870s, he was advertising his company as: George Scott, inventor and builder of Scott’s patent elevator for stores, warehouses and factories. Manufacturer of pumps, tackle blocks, trucks, hoisting wheels, tobacco casing, water wheel crabs, oars, capstans and bars, distill tubs, etc. Second-hand hoisting wheels always on hand.[4]

While his advertisement emphasized the production of freight elevators for various settings, it also indicated the full range of his product line. Thus, although Scott was well known as an elevator builder, his company belonged to the subset of VT manufacturers for whom elevators constituted only one aspect of their business.

His reputation as an elevator builder was highlighted in an 1878 article that described a test of his 1869 safety device in the Louisville Hotel:

“Mr. George Scott, the elevator builder, yesterday attached his patent clamp or brake to the freight elevator at the Louisville Hotel. An experiment to test the reliability of the improvement afforded quite an interesting entertainment to the guests of the house and others who gathered in a crowd within the office. After adjusting the brakes just as they are hereafter to remain, he put three thousand pounds of freight on the elevator, and then with a cold chisel cut the iron rope. The elevator fell about 4 in., when the heavy clamps closed on the iron columns, and held it still with a grip which no power could have sundered.”[5]

Scott’s public demonstration of his safety device followed a pattern established by other VT manufacturers. The demonstration also indicated to the public that the safety, while a critical feature of Scott’s elevators, could also be purchased for use on existing elevators. In fact, the freight elevator in the Louisville Hotel had not been built by Scott.

The first evidence of Scott’s commercial activity outside of Louisville appeared in an article published in the Clarksville, Tennessee, Leaf-Chronicle Weekly on October 20, 1882:

“Mr. George Scott, of Louisville, Ky., is now in the city, putting elevators in Mr. Frech’s house. Parties wanting new elevators put in or old ones repaired, will do well to call on him within the next few days at the Southern Hotel. Mr. Scott built nearly all the elevators in this city. He is thankful for the very liberal patronage heretofore given him, and will give strict attention to future orders.”

This brief account requires a bit of “unpacking.” The phrase “Mr. Frech’s house” refers to Henry Frech’s general store, which occupied a three-story building in Clarksville. Scott’s presence in the Southern Hotel, and his willingness (and availability) to meet with prospective customers, followed a common business practice employed by other VT manufacturers. Orders would be solicited, specifications confirmed and, upon receipt of payment, a disassembled elevator would be shipped to the customer. The manufacturer would also, typically for an additional fee, send a representative to oversee the elevator’s installation.

Lastly, the statement that Scott had “built nearly all the elevators in this city” is intriguing. Clarksville is located on the Tennessee/Kentucky border, approximately 200 m from Louisville. The 1880 census recorded a population of 3,880, thus the city embraced a relatively small business community. How Scott became aware of this potential market for his elevators is unknown. However, the publication of a lengthy list of references in 1883 revealed that Scott had built freight elevators for seven Clarksville businesses. Thus, given the city’s size, Scott could have easily built the majority of its elevators (interestingly, the list that did not include Frech’s general store).

The omission of Frech from the reference list indicates that it was prepared prior to October 1882. In addition to referencing his work in Tennessee, the list also sheds light on the extent of Scott’s activity in Kentucky and throughout the South.[7] In addition to Louisville, Scott’s Kentucky work included elevators built for businesses in Frankfort, Glasgow, Henderson, Lawrenceburg, New Haven, New Hope, Owensboro, Paducah and Shepherdsville. In addition to Clarksville, Tennessee, Scott built elevators for businesses in Alabama (Eufaula and Montgomery), Arkansas (Fort Smith) and Georgia (Americus and LaGrange). Scott’s Southern activity (outside of Kentucky) involved the production of 20 elevators for 16 individual clients; within Kentucky he produced 54 elevators for 32 individual clients.

A critical missing piece of information concerns the time frame covered by these installations (thus far, the dates of only two installations have been confirmed: one in 1880 and one 1881). Thus, while Scott’s annual sales over a discrete period of time cannot be determined, it may be reasonable to assume he was viewed as a successful VT manufacturer. An 1883 advertisement described Scott as a:

“Manufacturer and builder of steam, gas, water and hand power elevators for stores, warehouses, hotels and distilleries. Also, dealers in store-trucks, pumps and tackle blocks. Scott’s patent safety clutch or catch attached to any of these elevators when so ordered. They are warranted to be perfectly safe. When ordering give hatch size and height of each story. Manufacturer of Chamber’s patent hatch doors.”[7]

Although he remained focused on building freight elevators, he had clearly expanded his production line beyond hand-powered machines. He was also still building his safety device (it is of interest that it was not a standard feature, but was only available “when so ordered”), and he was now manufacturing “Chamber’s patent hatch doors.”

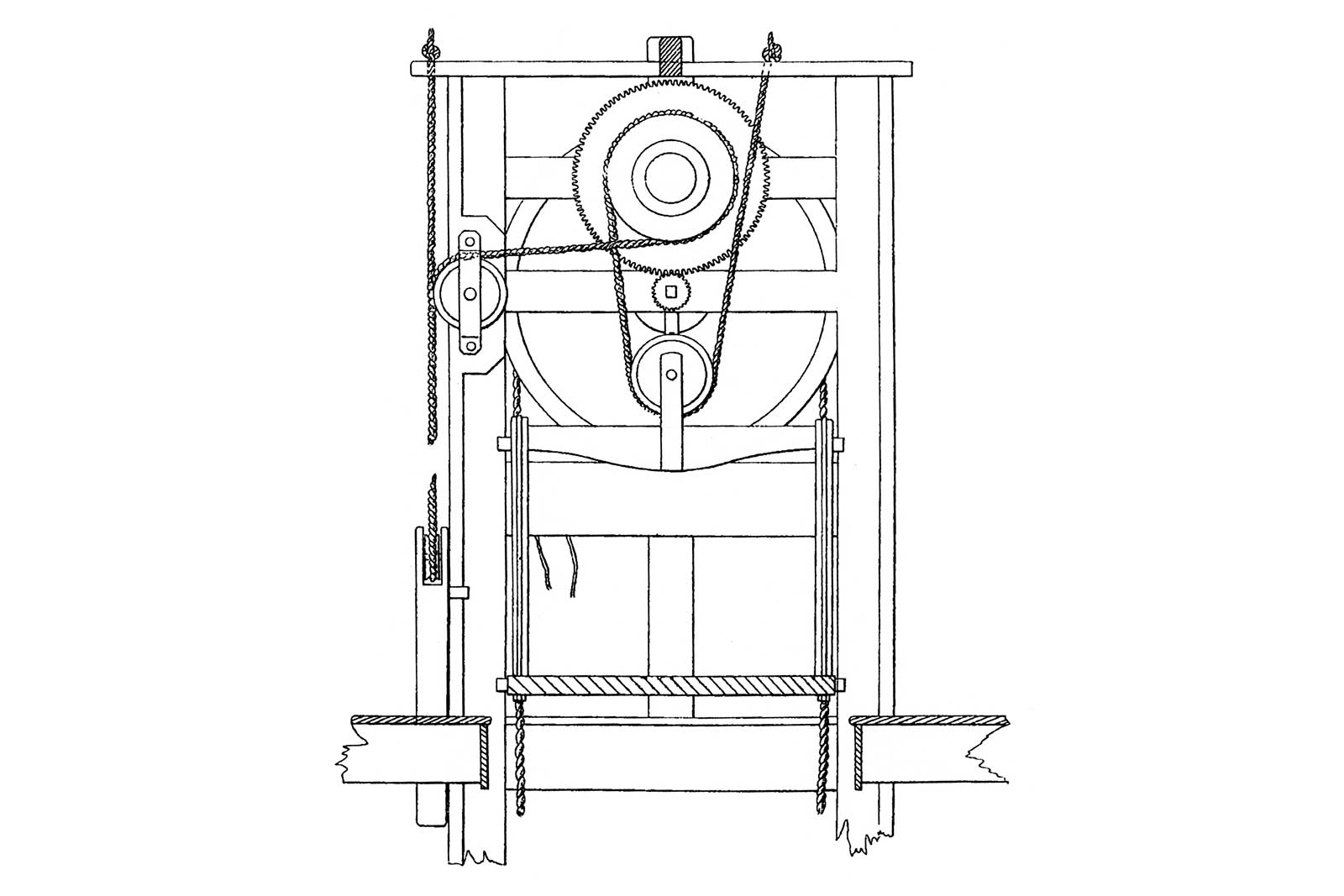

The latter reference, that Scott was building someone else’s patented device, was, in fact, a common feature of many VT advertisements during this period. This typically took the form of an acknowledgement that a company had an arrangement to build or was the agent for another VT company’s patented system or a particular inventor’s device. In this case, Scott was marketing a system patented by Josephus C. Chambers of Cincinnati: Self Closing and Locking Hatchway-Door, U.S. Patent No. 248,404 (October 189, 1881). The manner in which these types of business deals were made, and why particular designs were deemed suitable for marketing, remains a mystery. Why and how Scott chose Chambers’ design is a good example of this type of historical enigma. When he patented his hatchway device — his only elevator-related patent — Chambers was employed in a Cincinnati dry goods store and he was actively working on a variety of designs concerning the use of electricity as a means of treating medical issues (which became the subject of numerous patents). Thus, his resume does not speak to an understanding of or a sustained interest in VT technology that resulted in a device that would have naturally attracted Scott’s attention. Chambers’ design concerned a system common to other such schemes in which brackets were mounted on the sides of the platform that were intended to open and close sliding hatchway covers as the car passed through the shaft (Figure 4).

A final piece of evidence of Scott’s prominence as an elevator builder dates from 1885 and, perhaps, gives him “pride of place” as the first VT manufacturer to achieve a particular distinction. The September 18, 1885, edition of the Louisville Courier-Journal included a lengthy series of articles reporting on the success of the city’s celebration of its role in the American tobacco industry. The events included a parade through the streets of Louisville that featured a large number of floats, one of which was sponsored by Scott: “George Scott’s Steam and Hand-power Elevator Co. (presented a) large float driven by four coal-black horses, (the float) represented a hand elevator in miniature, in full operation.” Thus, Scott may have been the first VT manufacturer to participate in a major civic parade with a float that displayed a working model of an elevator.

This examination of George Scott’s business revealed how his commercial success extended well beyond his city and state. In his multi-state activities, Scott was not unique. Other regional manufacturers were also active in multiple states, and they represented an important aspect of the VT industry in the 1880s. They also helped to establish business practices that informed the industry’s continued development throughout the remainder of the 19th century. The conclusion of this three-part series will examine the emergence of an industry sector that supplied many VT companies with elevator call systems (typically referred to as elevator annunciators). The ability of the VT industry to elicit a significant commercial response from another industry sector also serves as further evidence of its maturity during this period.

References

[1] George Scott advertisement, Edwards’ Fourth Annual Directory of the … City of Louisville for 1868-69, Louisville: Southern Publishing Co. (1868).

[2] John William Wallace, Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the United States, October Term, 1874, Washington, D.C.: W.H. & O.H. Morrison (1876).

[3] “Yesterday’s Fire,” Courier-Journal (August 4, 1871).

[4] George Scott advertisement, Kentucky State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1876-77, V.4, Louisville: Courier-Journal Book and Job Printing Rooms (1876).

[5] “Local Brevities,” Courier-Journal (March 17, 1878).

[6] Untitled, Leaf-Chronicle Weekly (Clarksville, Tennessee) (October 20, 1882).

[7] George Scott advertisement, Kentucky State Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1883-4, V.4, Detroit: R.L. Polk & Co. and A.C. Danser (1883).

[8] “Our Tobacco Jubilee,” Courier-Journal (September 18, 1885).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.