The Chicago Cubs and the 2016 CTBUH Best Tall Building Symposium

Feb 1, 2017

Buildings from around the world are awarded, and a connection to the World Series is explained.

The 15th Annual Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) Best Tall Building Symposium occurred on November 3, 2016, on the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. The event consisted of three sessions (each of which included four presentations), followed by a reception and awards dinner. This event remains unique in bringing together architects, engineers, developers, consultants, suppliers and clients to discuss and celebrate the challenges and achievements associated with tall-building design. Shanghai Tower in Shanghai was awarded as the 2016 Best Tall Building, with Regional Best Tall Building Winners as follows:

- Americas: VIA 57 WEST, New York City (NYC)

- Asia & Australasia: Shanghai Tower

- Europe: The White Walls, Nicosia, Cyprus

- Middle East & Africa: The Cube, Beirut, Lebanon

CTBUH stated this year’s selection was “the most competitive yet, with winners selected from a pool of 132 entries. The Best Tall Building Worldwide was named from the winners of the four competing regions in the world, from nominees representing a total of 27 countries.” Additional building/product awards presented were the Performance Award to Taipei 101 in Taipei, the Urban Habitat Award to Wuhan Tiandi Site A in Wuhan, China, the 10-Year Award to Hearst Tower in NYC, and the Innovation Award to the Pin-Fuse Seismic System. The following experts in the field were given awards, as well:

- Lynn S. Beedle Lifetime Achievement Award: Dr. Cheong Koon Hean, CEO, Housing & Development Board of Singapore

- Fazlur R. Khan Lifetime Achievement Medal: Ron Klemencic, Chairman and CEO, Magnusson Klemencic Associates

In addition to presentations that addressed the winning projects and lifetime achievement awards, the symposium also included presentations on two regional Best Tall Building finalists: Benjamin Romona (founding principal of LBR&A Architectos) presented on the Torra Reforma in Mexico City, and Wolf D. Prix (Design Principal and CEO, COOP Himmelblau) presented on the European Central Bank building in Frankfurt, Germany.

Two of the presentations mentioned vertical transportation. Prix highlighted the presence of “interchange floors” in the European Central Bank building that were served by express elevators. The architectural importance of these contemporary sky lobbies was described as follows:

“Connecting and transitioning levels between the two tower volumes divide the main atrium space horizontally into three separate atria, breaking down the public space into a more manageable scale of 45-60 m (148-197 ft.) in height. Within each atrium, interchange platforms and pedestrian bridges recall urban streets and squares, while hanging gardens regulate interior temperature to create a pleasant climate, inviting communal activity.”[1]

The European Central Bank building features 18 thyssenkrupp elevators, eight of which are TWIN® elevators.

In their presentation of the Shanghai Tower, Jianping Gu (general manager, Shanghai Tower C&D) and Grant Uhlir (managing director, principal, Gensler) noted the presence of the world’s fastest elevators in the building. These Mitsubishi electric units are now capable of operating at 20.5 mps. The technical challenges associated with design were numerous, resulting in an aerodynamic pressurized car, active guide rollers, a 310-kW traction machine, ceramic brake shoes and Mitsubishi Electric’s sfleX-rope (ELEVATOR WORLD, April 2012, June 2013 and July 2013).

The Shanghai Tower’s high-speed elevators serve as a reminder of the challenges associated with elevatoring skyscrapers, as well as a reminder that specific building types represent very different types of vertical-transportation problems. The building typology that concerns the CTBUH is, of course, the “tall building.” At the conclusion of the awards symposium, CTBUH Executive Director Antony Wood reminded the audience (as he has in past years) that the Best Tall Building Award is not intended for the tallest building, but the best tall building as defined by CTBUH. The CTBUH “Criteria for the Defining and Measuring of Tall Buildings” describes/defines a tall building as follows:

“There is no absolute definition of what constitutes a ‘tall building.’ It is a building that exhibits some element of ‘tallness’ in one or more of the following categories:

- a) Height relative to context

- b) Proportion

- c) Tall building technologies: vertical transport technologies, structural wind bracing as a product of height, etc.

“Although number of floors is a poor indicator of defining a tall building due to the changing floor-to-floor height between differing buildings and functions (e.g., office versus residential usage), a building of perhaps 14 or more stories — ormore than 50 m (165 ft.) in height — could perhaps be used as a threshold for considering it a ‘tall building.’ The CTBUH defines ‘supertall’ as a building over 300 m (984 ft.) in height and a ‘megatall’ as a building over 600 m (1,968 ft.) in height.”[2]

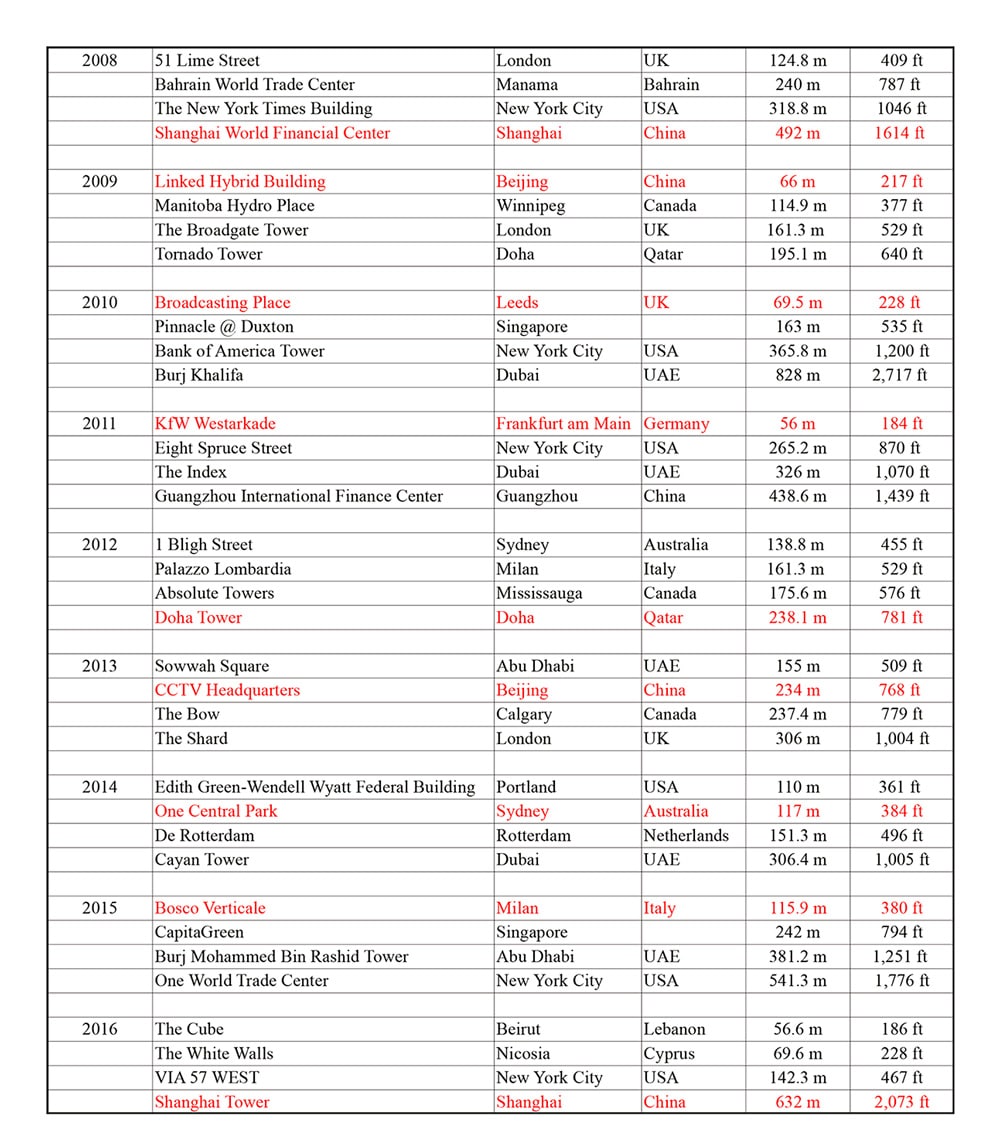

Although this definition divides tall buildings into three specific categories (tall, supertall, and megatall), for the purposes of the Best Tall Building Award, all buildings that satisfy this somewhat general definition are considered equal contenders. The jury has, throughout the award’s nine-year history, moved from one extreme to another, with the shortest regional finalist winning four times, the second-shortest building winning twice, and the tallest building winning only three times (Table 1). While these results support Wood’s statement about the awards process, CTBUH appears to be avoiding the fact that the architectural, engineering and vertical-transportation problems presented by a 56.6-m (186-ft.) building are not comparable to those of a 632-m (2,073-ft.) building. (These are the respective heights of this year’s shortest and tallest buildings.)

An additional factor in judging is the impact of a building on its urban habitat. CTBUH has increasingly and appropriately focused attention on the urban design implications of tall buildings. However, the urban impact of a “tall” building, with regard to building population size and implications for the adjacent urban habitat and infrastructure, is significantly different from that of a megatall building. Thus, evaluating these diverse buildings as if they represented the same type of architectural and urban design problem is problematic. It may be time for CTBUH to consider separating the awards into different categories. This separation might also increase the number of submissions, particularly with regards to the tall-building category, which could result in an expansion of the organization’s influence on architectural and urban design.

As it has since 2008, CTBUH published a book that highlights the various award nominees and winners: Best Tall Buildings: A Global Overview of 2016 Skyscrapers (Routledge). One of the consistent strengths of CTBUH has been providing as much information as possible about the participants involved in a particular project: clients, owners/developers, architects, engineers, suppliers and consultants. This year, there was, however, a noticeable change in the format used to list project consultants and suppliers. Whereas past awards books used the headings “Consultants” and “Suppliers,” the 2016 awards book used “Other CTBUH Member Consultants” and “Other CTBUH Member Suppliers.” According to Wood, this change was part of an editorial strategy designed to manage the steadily increasing amount of information provided for each project. The CTBUH’s editorial strategy for the 2016 awards book was defined as follows:

- All primary involvement is listed, where known, irrespective of CTBUH membership, which includes: owner; developer; architect; structural engineer; mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineer; and main contractor.

- All other consultants or suppliers are listed only if they are CTBUH members.

This editorial decision is, perhaps, the reason for the dramatic reduction in the number of vertical-transportation consultants identified in the awards book, listed as:

- MovvéO Ltd., U.K.

- WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff, U.K.

- Edgett Williams Consulting Group Inc., U.S.

- Lerch Bates Inc., U.S.

- SYSKA Hennessy Group, U.S.

- Van Deusen & Associates, U.S.

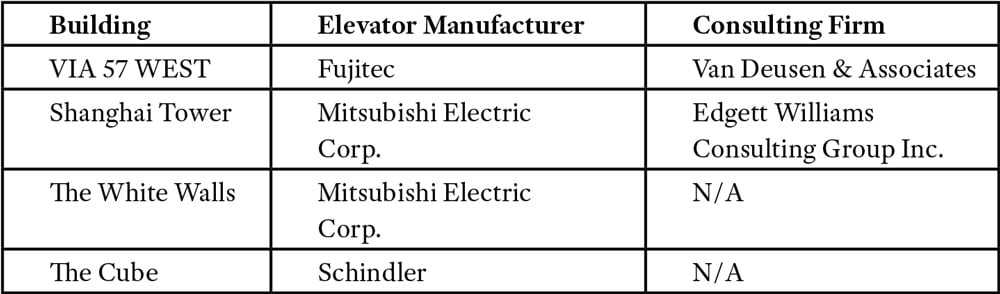

This editorial decision also made it difficult to identify the elevator suppliers for the four regional winners. A search for this information revealed three different manufacturers and the fact that two project teams included a vertical-transportation consultant (Table 2).

The vertical-transportation industry had an overt presence in Chicago in that Otis, KONE and Schindler were identified as sponsors of the symposium and awards dinner. Thus, as has been the case in past years, the industry was both present and represented in a variety of ways at this important event.

The 2016 symposium was also somewhat overshadowed by the events of the previous evening, when the Chicago Cubs, with a dramatic 10th-inning rally in game seven, won their first World Series in 108 years. The link between this sporting event and tall buildings may, at first glance, appear nonexistent. However, the history of skyscrapers — and vertical transportation — provides a powerful connection. One of the buildings honored by the CTBUH was the Hearst Tower in NYC, which received the 10-Year Award. This award is intended to recognize:

“Proven value and performance in a tall building, across one or more of a wide range of criteria, over a period of 10 years since its completion. This award gives an opportunity to reflect back on buildings that have been completed and operational for at least a decade, and acknowledge those projects which have performed successfully, long after the ribbon-cutting ceremonies have passed.”[1]

One of the Hearst Tower’s defining characteristics is that it appears to sit atop the original 1928 Hearst Building. The connection with the Chicago Cubs and CTBUH lies in the fact that the Cubs’ last World Series victory occurred in 1908, the year the Singer Building in NYC was completed. While history does not repeat itself (things are never that simple), there are often intriguing parallels between past and present events. The Singer Building project involved the expansion of an existing building that also served as the base for the skyscraper. Thus, this project was, in many ways, a precedent for the later Hearst Building.

Ernest Flagg, the Singer Building’s architect, was also a well-known critic of tall buildings, and he had expressed concerns about their potential negative impact on the urban fabric of NYC as early as 1896. Flagg’s concerns focused on issues of daylight, air and urban congestion — issues that lie at the heart of the current discussion about well-designed urban habitats. The Singer Building also represented the first large-scale test of the electric traction elevator in a high-rise setting, a feat comparable to the innovative elevator systems found in Shanghai Tower. The comparison of this historical precedent with contemporary parallel projects serves as a reminder that many “contemporary” conversations have been going on for a long time. It also, perhaps, reminds us that there is often as much to be gained by looking back to the past as there is in looking forward to the future (or being focused on the present). As with all things in life (and vertical transportation), it is a question of balance.

References

[1] Best Tall Buildings: A Global Overview of 2016 Skyscrapers (Routledge: 2016).

[2] “CTBUH Criteria for the Defining and Measuring of Tall Buildings” (www.CTBUH.org).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.