The Dahlstrom Metallic Door Co. (1925)

Mar 24, 2025

In 1924, the Dahlstrom Metallic Door Co. celebrated the 20th anniversary of the company’s founding. The following year, it published its first catalog devoted to elevator doors. This event highlighted the company’s expansion of its product line into the vertical-transportation (VT) landscape and the company’s continued growth and commercial success.

The company was established by Charles P. Dahlstrom (1872-1909). Dahlstrom was born in Sweden, on the island of Gotland. He attended public school there until the age of 12, after which he attended a trade school in Stockholm. Following graduation, “he served an apprenticeship in the trade of tool and die making.”[1] In 1890, he immigrated to the United States. He first settled in Buffalo, NY, where he was employed by the Spalding Machine & Screw Co.; after a few years, he left to work in Chicago and Milwaukee, after which Spalding “persuaded him to return to Buffalo.”[1] However, Dahlstrom soon departed Buffalo again (for the final time), and moved to Pittsburgh where he worked for the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co.

In 1899, he moved to Jamestown, NY, to work for the Art Metal Construction Co., which specialized in the manufacture of metal office furniture. He signed a five-year contract with the company and, during this period, began to pursue the design of metal doors. His efforts resulted in one patent: Metallic Door, U.S. Patent No. 747,149 (December 15, 1903).

On the strength of this single patent, he founded the Dahlstrom Metallic Door Co. in 1904 (Dahlstrom later earned additional patents related to metal door design). His entrepreneurial spirit and business acumen was such that in 1905 the fledgling company was awarded a contract to provide more than 2,000 metal doors and trim for the new 22-story United States Express Building in NYC. The quality of the products and the successful completion of this project ensured the company’s future success.

In 1907, Dahlstrom installed its first metal elevator doors in the Wells Fargo Building in Portland, Oregon. The impact of this “first” is difficult to judge, as is the pace at which the company began to manufacture elevator doors. The company’s first catalog, published in 1913, somewhat downplayed the importance of elevator doors within the overall product line.[2]

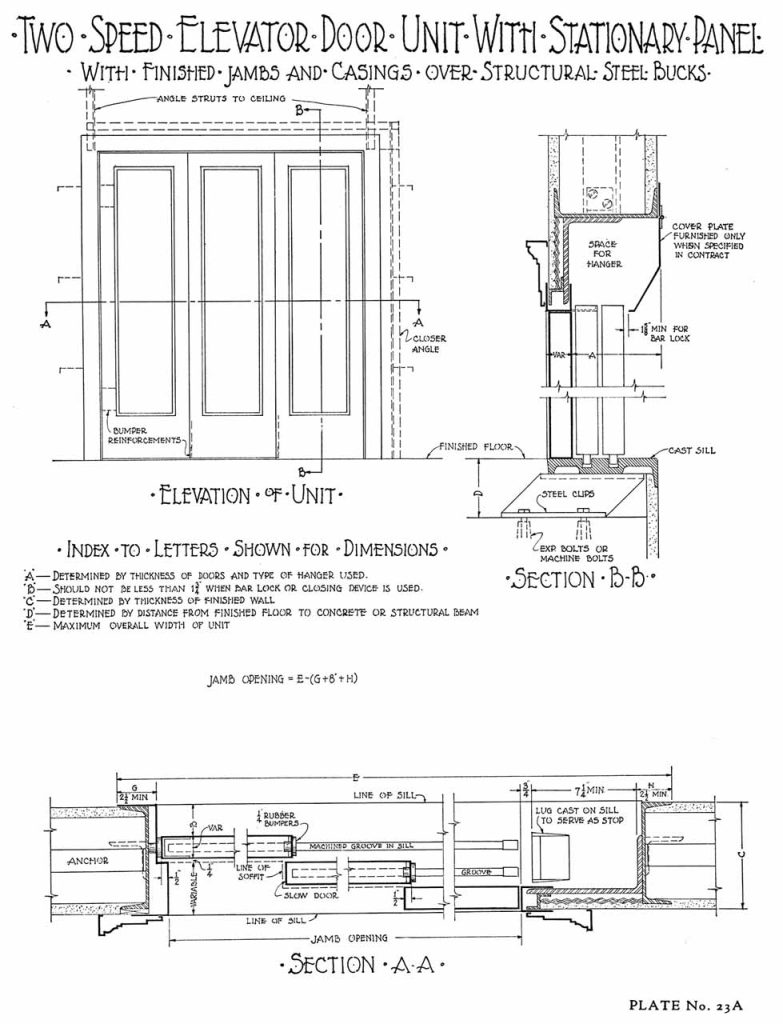

The catalog included 30 plates that featured detailed drawings of door types and installations; however, only six plates were devoted to elevator doors. These drawings depicted steel elevator doors, steel elevator enclosures, two-speed sliding elevator doors with fixed panels, a collection of standard elevator door details and a steel elevator car.

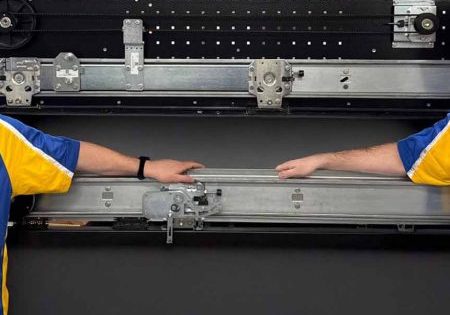

In addition to providing information on individual door design and operation, the drawings also provide insights into the challenges associated with building elevator doors. While Dahlstrom specialized in building metal doors, it did not manufacture any of the hardware needed to operate their doors (hangers, door operators, etc.). The drawings included representations of door hangers and related hardware, and they identified the components’ manufacturers. The suppliers listed included the Reliance Ball Bearing Door Hanger Co. (NYC), the Diamond Door Hanger Co., Inc. (Brooklyn, NY), P & F. Corbin (New Britain, Connecticut), the Russel & Erwin Manufacturing Co. (New Britain, Connecticut) and Stanley Works (New Britain, Connecticut). The Reliance and Diamond companies specialized in elevator door hangers and operators, while the others primarily manufactured door hardware.

By 1925 Dahlstrom’s production of elevator doors had reached the point that it warranted a dedicated catalog. The result was an 86-page book, titled Dahlstrom Elevator Entrance Enclosures, which included sections on elevator enclosures, standard door designs and types, casing, scribes and pilasters, hardware, construction details, glass, finishes, selected Dahlstrom installations and specifications. The introduction to the section on elevator enclosures captured Dahlstrom’s enthusiasm for its products, as well as the dynamic nature of the VT world in the mid-1920s:

“No one can watch the constant flow of people through the portals of our large buildings and see them apparently swallowed up by openings in the lobby walls, without a feeling of wonderment over the developments which have attended the evolution of our modern office building. Conveniences and safeguards which were unknown a few short years ago are now in common use and the absence of them would bring forth much more notice than does their presence. The development of the elevator and the shaft which encloses it has kept pace with other features of building construction. In this connection the modern elevator enclosure has played an important part. Contrast the old type open grille work around elevators with the modern installations of Dahlstrom enclosures, and the vast strides made in recent years will at once become apparent. It is a distinct source of pride with us that it fell to our lot to pioneer this important achievement in modern buildings.”[3]

The replacement of “open grille work” elevator doors and shaft enclosures, which allowed waiting passengers to catch glimpses of the cars as they traveled up and down with the solid walls of the “modern” elevator enclosure, had the — perhaps unexpected — result of enhancing the mystery associated with riding elevators — with prospective riders “apparently swallowed up by openings in the lobby walls.” However, the use of glass panels in Dahlstrom’s doors meant that waiting passengers would have been aware of the arrival and departure of the car as its lighted cabin gradually appeared and disappeared in the shaft.

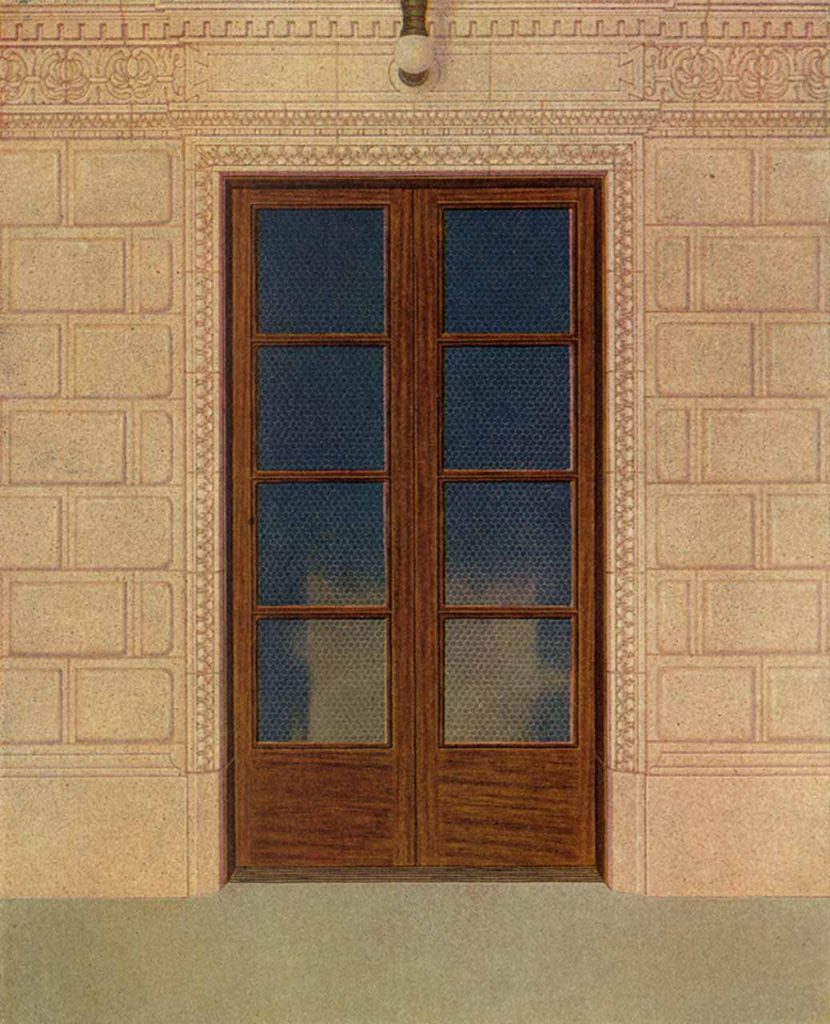

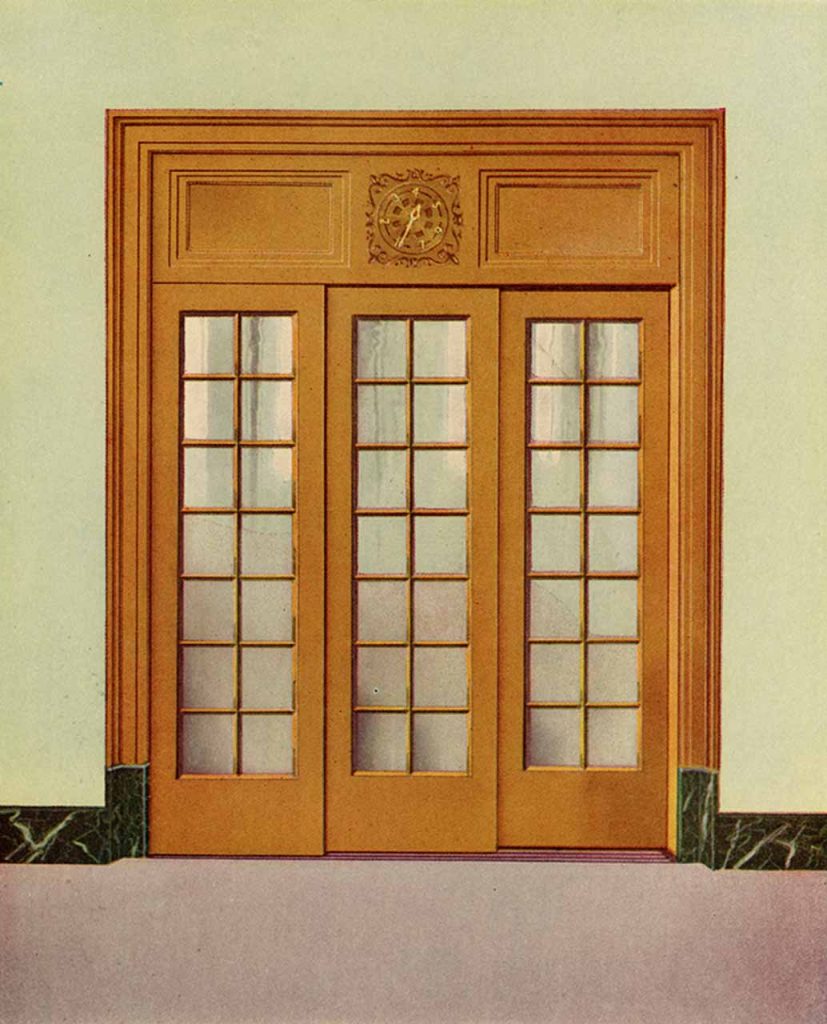

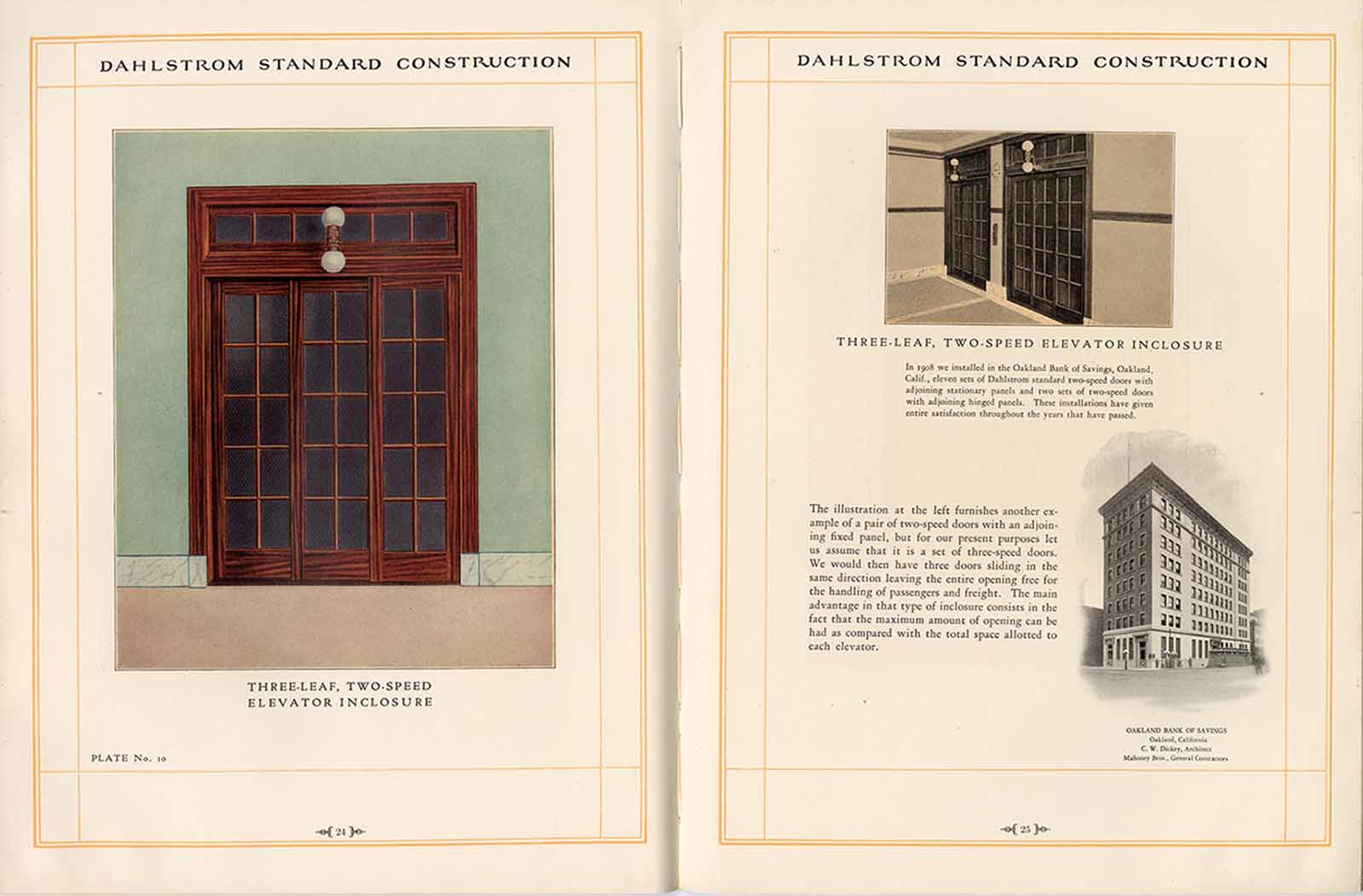

Dahlstrom’s presentation of its elevator enclosure designs included 10 two-page spreads, each of which depicted a completed installation (each spread featured a color rendering, a photograph of the installation and a photograph of the building) (Figure 1). A sample of the color renderings reveals the variety and quality of Dahlstrom’s designs (Figures 2 – 4).

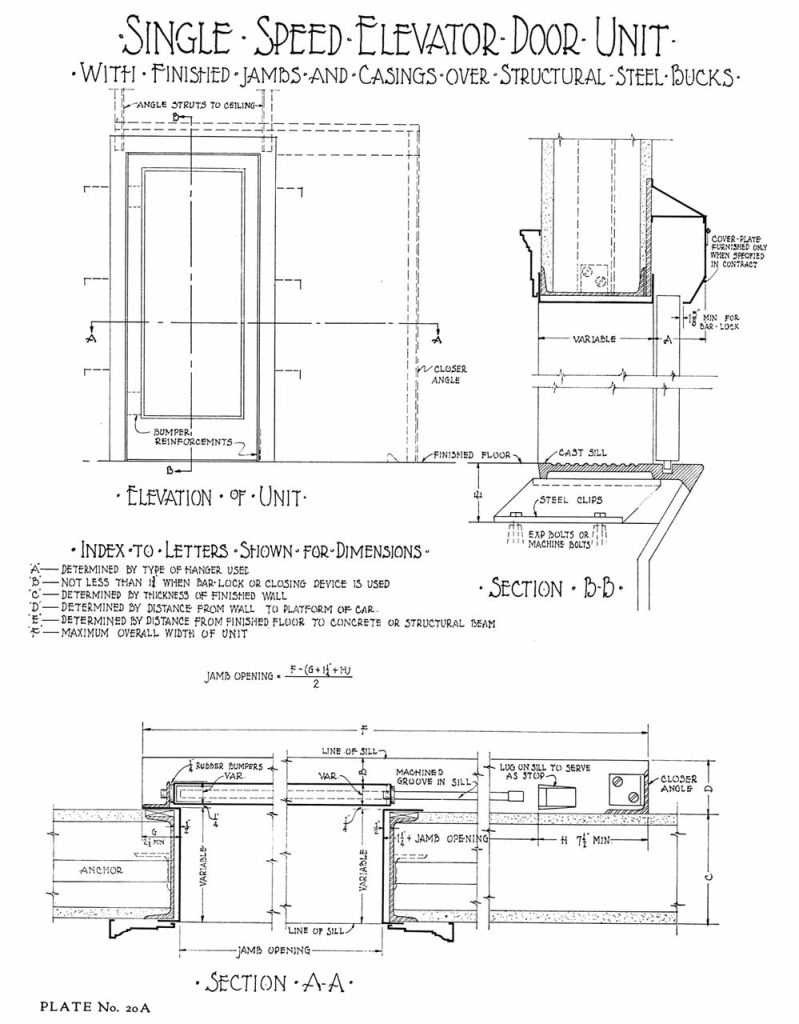

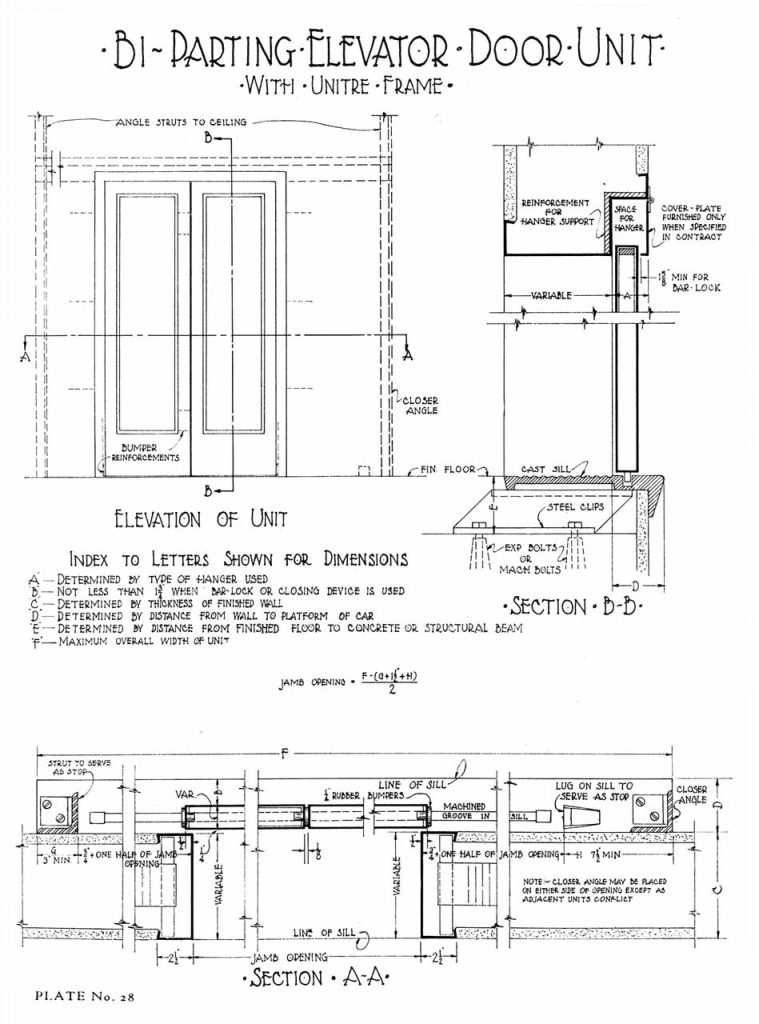

This material was supplemented by the Construction Details section, which featured 11 pages of drawings, each of which included an elevation, plan and section of a specific door type. The drawings for the doors illustrated in Figures 2–4, when coupled with their color renderings, yield a thorough understanding of each design (Figures 5–7).

An interesting difference between the 1925 drawings and those included in the 1913 catalog is the absence of suggested hardware suppliers. The 1925 drawings simply included a blank “space for hangers.”[3] The catalog’s description of door hardware emphasizes the fact that Dahlstrom continued to rely on other manufacturers to fulfill this critical need:

“The selection of hardware for elevator enclosure doors is an important item, since the smoothness of operation depends in a great measure on the type of hanger and closer used. Therefore, the merits of various kinds and types of hangers and closers should be carefully considered. Obviously, the question of price is not the main consideration, but rather the mechanical perfection of the device itself and its adaptability to the work required of it. The hardware requirements are governed to a certain extent by local regulations which vary considerably in the different states and cities … The hangers may be classified under four headings, viz., single speed, two-speed, three-speed and bi-parting. The main considerations in the selection of a hanger are ease of operation and durability … For manually operated elevators the doors may be equipped with automatic self-closing devices or with bar locks.”[3]

The catalog also noted that standard door hardware “should be supplemented by electric interlocks which prevent the car leaving any landing until the doors” have closed. Interlocks were not, however, included in the company’s standard scope of work:

“This contractor shall furnish and set complete elevator entrance enclosures on all floors as shown on the drawings. He shall include the steel buck units, sills with nosings on shaft side, doors, jambs, trim, hangers, hanger housing, door closers, closer supports, glass and rubber glazing channels, making a complete installation. This contractor shall not furnish such items as electric interlocks, signals or landing lanterns.”[3]

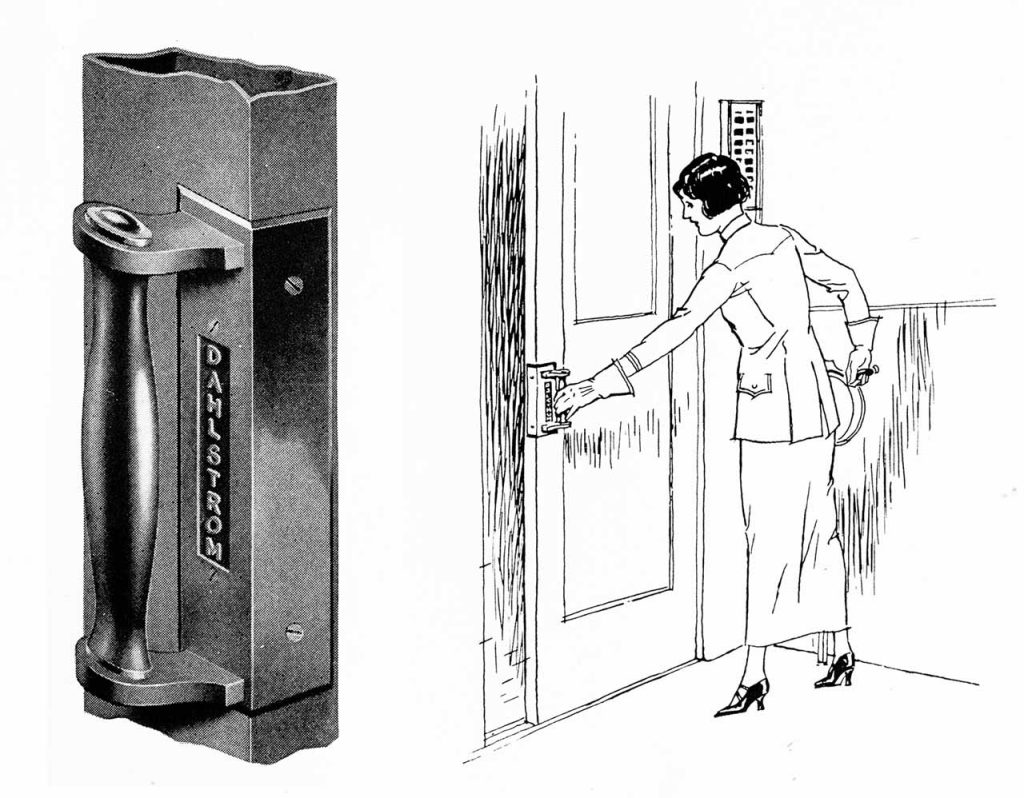

Apparently, they relied on the elevator manufacturers and/or other suppliers to furnish the door interlock and signal systems. The only piece of door hardware manufactured by Dahlstrom was a “protecting plate and handle,” which was “designed to protect the finish of the doors against the constant action of the operator’s hands” (Figure 8).

In the catalog, Dahlstrom also emphasized the critical role its installers played in achieving the best possible result:

“No matter how carefully fabricated and finished, if the material is improperly installed it will fail to give the measure of satisfaction which should result from every elevator enclosure. Satisfactory results can only be accomplished by placing the work in experienced and responsible hands. Placing the entire responsibility on the Dahlstrom Metallic Door Co. insures the proper installation of the enclosures. The rough bucks and sills will be correctly set and anchored into the masonry; the finished materials will be placed in true alignment; the hangers and other hardware items will be adjusted to function properly; the completed installation will be cleaned off and left in a first-class condition. As a result, the architect and owner will be relieved of the many irritating details which result from divided responsibility or from placing the work with an inexperienced and irresponsible manufacturer.” [3]

In addition to the 10 projects mentioned in the section on elevator enclosure designs, the catalog included a list titled “A Few Dahlstrom Installations,” which referenced 33 buildings that employed their door systems. The buildings, scattered across the U.S., provide evidence of the company’s national presence. The list also included two international installations: Dahlstrom provided elevator enclosures for the Tata Iron & Steel Building in Sacchi, India, and the Robert Dollar Building in Shanghai, China. These installations raise questions about the extent of Dahlstrom’s international business, as well as questions about the international scope of the American VT industry during this period.

A critical piece of information missing from the Dahlstrom installation references are the names of the elevator manufacturers. This information would provide insights into the overall nature of VT industry practice in the 1920s and the commercial relationships between elevator manufacturers and component suppliers. This topic will be the focus of a future article.

References

[1] John P. Downs, Editör, History of Chautauqua County, New York, And Its People, Cilt III, Boston: American Historical Society (1921).

[2] Hollow Metal Construction, Dahlstrom Metallic Door Co., Jamestown, NY. (1913).

[3] Dahlstrom Elevator Entrance Enclosures, Dahlstrom Metallic Door Co., Jamestown, NY. (1925).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.