by Sasha Bailey

Indoor air quality has become an increasingly important and relevant topic for building owners and occupants in recent years. With more and more information available to the public on air quality issues, including the potential negative effects of off-gassing, the evaporation of volatile chemicals and other emissions, it is imperative for building product manufacturers to focus on eliminating indoor air quality issues associated with their products.

To better understand indoor air quality issues, it is beneficial to have a background on how it relates to buildings and building occupants. In particular, Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) has been studied for the last few decades relevant to building occupants’ health. Anyone can be affected by SBS, but office workers are most at risk, because they usually do not have control over their work environments. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines SBS as “situations in which building occupants experience acute health and comfort effects that appear to be linked to time spent in a building, but no specific illness or cause can be identified. The complaints may be localized in a particular room or zone, or may be widespread throughout the building.”

The World Health Organization Committee released a report in 1984 suggesting up to 30% of new and renovated buildings worldwide could be subject to excessive complaints about indoor air quality. Some common complaints related to indoor air quality and SBS include the following: headaches; eye, nose and throat irritation; dizziness; nausea; fatigue; skin problems and difficulty concentrating. Most cases of SBS occur in offices, although buildings such as schools, libraries and museums often have cases due to the large volume of people occupying these spaces. Widely agreed upon contributing factors of SBS include inadequate ventilation, chemical contaminants from indoor sources like carpet or paint, chemical contaminants from outdoor sources such as vehicle exhaust or plumbing vents, and biological contaminants like mold, bacteria and viruses.

One of the main culprits in decreased indoor air quality and SBS is volatile organic compounds (VOC). VOCs are emitted as gas from various solid and liquid products all around us every day. Many building materials that surround us have the potential to emit VOCs. Some examples include paints, carpet, furniture, wood products, adhesives, as well as indoor maintenance agents such as pesticides, cleaning products, office equipment and even permanent markers. Some of the effects associated with the emission of VOCs mirror those found in SBS cases and can include headaches, nose and throat irritation, dizziness, skin rashes or fatigue. It is important to note that not all organic chemicals contribute to adverse health effects; it is contingent upon the toxicity level of the substance and the concentrations and exposure for humans. It is no secret that Americans spend a majority of their time indoors. Unfortunately, EPA studies have shown that several VOC levels are two to five times higher indoors than outdoors. As a result, the EPA has developed many resources, such as the Building Air Quality Action Plan, available to building owners and manufacturers who want an easy-to-understand path for transforming their building from its current conditions and practices to a successful institutionalization of good indoor air quality management practices.

As more becomes known about the adverse effects of poor indoor air quality on tenant health, productivity and attendance, it is clear that a responsibility lies with the construction and leasing industry. Building product manufacturers act as the front line on this issue and, therefore, are in a unique position to make positive changes to the environments in which we operate. Forward-thinking companies have begun to utilize tools like life-cycle assessments to help them identify potential issues with their products. Some of those issues include identified toxins within their manufacturing processes that can adversely affect their employees’ health, as well as product emissions or off-gassing that can continue well after a product’s installation. The life-cycle assessment technique allows companies to assess environmental impacts associated with all the stages of a product’s life, from cradle to grave. After identifying potential air quality problems within a given process or product component, it then falls upon manufacturers to seek the source, often within their supply chains.

In the past, it was acceptable for manufacturers to claim responsibility only for what occurred within their own facilities. However, in today’s global economy, that is no longer the case. Manufacturing companies are now expected to not only be aware of all that happens within their own walls, but to hold their suppliers accountable, as well. To this end, quite a few Fortune 500 companies, as well as state and local governments, have begun working to identify chemicals of concern and document them. To date, there are more than 20 such lists compiled by states, corporations, the EPA, European Union, etc. The compilation of so much data on toxins and chemicals has allowed for the gradual phase-out or replacement of chemicals of concern to become a more manageable task for manufacturers. Once identified, finding alternative materials or products can sometimes be a challenge. However, with the growing global emphasis on sustainability and green construction, more and more companies are now offering healthier products at the same or slightly increased pricing. This was not the case several years ago.

Once a manufacturer has found an appropriate replacement product and adjusted manufacturing processes accordingly, it is important to make it clear to their buyers and buyers’ influencers that the improved product exists. In the past, simply marketing this information might have been sufficient, but with so much greenwashing (misleading claims about a product’s green attributes), it is now important to rely on reputable third parties to test and validate claims. Reputable and established product-certification services, such as Underwriters Laboratories (UL), have entered the environmental certification arena. Products can now be submitted to UL for placement within its testing chambers to evaluate emissions, off-gassing, toxicity, indoor air quality, etc. Famous for fire-rating testing, the generations-old company has now added reputability to environmental product claims.

Environmental claims can vary based on applicable product standards. For instance, the State of California has set strict standards for buildings’ indoor air quality, commonly referenced as Section 01350. Section 01350 covers public health and environmental considerations for building projects, including indoor air quality goals and procedures. Parts of these goals include limits on VOC levels and procedures for how to test building products for VOC-emission rates. Standards like these allow testing and certification bodies, such as UL, to validate and certify against them. This makes it possible for product manufacturers to provide not only an environmental claim, but also a third-party reviewed and validated label for their claim.

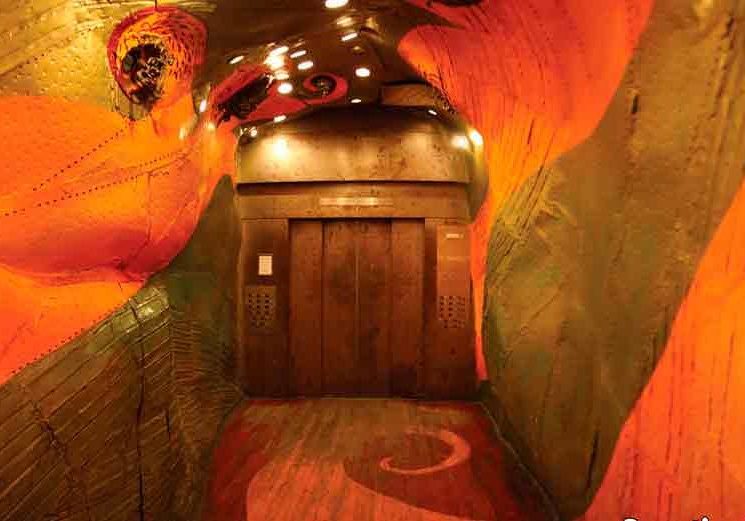

In the case of elevators, indoor air quality can be easily diminished in several places within the cab and the machine room. Products that contain high indoor air quality attributes include paints, coatings, adhesives and sealants used by the manufacturer, and wood or agrifiber products in the floor, walls or ceiling. Some good qualifying questions related to indoor air quality would be the following: if the manufacturer utilizes powder-coat processing or traditional solvent-based paints for its cab interiors; if wood-based products, such as particleboard or plywood, contain added urea-formaldehyde; and what kind of sealants and adhesives are used to adhere interior items. Standards like the U.S Green Building Council’s (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) rating system contain details and limit levels for indoor-source contaminants, such as the ones listed above. In particular, the Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) section on low-emitting materials can provide detailed information. For instance, IEQ credit 4.1 specifically identifies the VOC limit in grams per liter less water, for a variety of adhesives, including those used for carpet pad, drywall and panels, asphalt and ceramic tile. Additionally, IEQ credit 4.2, which pertains to paints and coatings, identifies standard VOC limits for specific items, such as bond breakers, cement coatings, shellacs, wood preservatives and traditional paints in various forms. By following strict guidelines established by commonly accepted standards like LEED, EPA or California’s Section 01350, it is easy to ensure optimum indoor air quality attributes in specified products for all new construction or renovation projects.

As a reaction to market demands for regulation or standards, several industries have begun to form alliances that have led to self policing. Some examples include the Carpet and Rug Institute (CRI), which is collaborating with major manufacturers to create an indoor-air quality rating for their floor coverings and carpet-pad adhesives. The standard that CRI created is the CRI Green Label Plus program. Green Label Plus sets acceptable limits for VOC emissions in micrograms per square meters per hour, along with testing methods for rating products.

When specifying products, it makes sense to ask the manufacturer to provide material safety data sheets (MSDS) and product attribute information sheets. This documentation can be used to substantiate indoor environmental quality or low-emissions claims beyond what is found in traditional brochures. By including the request for such documentation, the issue of greenwashing can be avoided, and the burden of proof relies on the product manufacturer, rather than the organization responsible for specifying or purchasing the product.

Green-building standards have gone a long way in helping to create processes during the design and construction phase that help to improve overall indoor air quality and reduce issues like SBS. Collaborative design is a trademark of green building and includes design professionals from various trades, including architects and landscape architects, mechanical and civil engineers, consultants and other external stakeholders, like owners or tenants. These collaborations help to avoid costly and inefficient last-minute design changes and issues between trades, as well as allowing for up-front decisions on minimum indoor-air quality performance, ventilation and chemical-pollutant source control. All of these factors play an important role in ensuring optimum indoor air quality for building occupants, upon completion. EPA makes several suggestions on reducing SBS, including pollutant source removal and modification, increasing ventilation rates, air cleaning and education, and communication. By working together, building owners, architects, general contractors, construction specifiers and product manufacturers have the opportunity to make significant positive changes in the buildings that we live, work and play in each and every day. Seeking out qualified and educated partners in product decisions means relying on manufacturers who can provide fact-based technical data and brochure claims. It is through educated industry partnerships that the health and wellness of building occupants will continue to improve in the coming years.

Reprinted from The BOMA Magazine, November/December 2012.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.