The Invalid Lift, Part One

Dec 1, 2018

Early elevators for handicapped persons emerged in 1869.

A primary focus of the vertical-transportation industry is the efficient movement of able- bodied persons. Of course, this (perhaps logical) focus does not mean that the needs of persons with disabilities are ignored. These important concerns are fully integrated into modern elevator design. However, this seamless integration also means these passengers — and their elevators — rarely receive special attention. The recognition that elevators play a critical role in assisting persons with disabilities dates from the mid-19th century. These early efforts focused primarily on residential systems. Unlike the present day, their purpose was highlighted with a distinctive label: the invalid lift.

The origins of the invalid lift are found in the development of dumbwaiters in the late 1840s, hand-powered freight elevators in the 1850s and steam-powered passenger elevators in the 1860s. The intersections between these worlds may be summarized in terms of familiarity, safety and promise. By the 1860s, thousands of dumbwaiters were employed in buildings in major cities throughout the U.S. The perfection of hand-powered freight elevators paralleled and supported the development of the safety devices needed in dumbwaiters. And, the appearance of the steam-powered passenger elevator in grand hotels hinted at the technology’s potential for future domestic application. However, the imagined widespread appearance of residential elevators failed to occur. This was due, in large part, to the technical challenges associated with domesticating the steam engine. (Mechanized residential elevators systems did not appear until the 1880s, following the development of small hydraulic engines).

Thus, while the widespread use of mechanized residential elevators never materialized, dumbwaiter manufacturers recognized that, by redesigning their existing systems, they could build simple and safe hand-powered passenger elevators. They also determined that the consumer group most in need of these elevators were persons with disabilities, known in the 19th century as “invalids.” While the irony of supplying hand-powered elevators to persons with disabilities to aid them in moving vertically through buildings cannot be avoided, there is ample evidence these systems were popular and used in a surprising number of homes.

One of the first references to invalid lifts appeared in the April 3, 1869, edition of the New York Herald, which published an advertisement for “Murtaugh’s celebrated dumbwaiters,” manufactured by James Murtaugh (1824-1902) of New York City (NYC). These dumbwaiters were the subject of an earlier history article (ELEVATOR WORLD, July 2010, “James Murtaugh’s Standard Dumbwaiters,” included in this month’s Online Extras). In his advertisement, Murtaugh noted that, in addition to dumbwaiters, he also manufactured “invalid elevators of the most approved pattern.”[1] This casual reference implies these elevators were common products and well-known to the American public.

In the 1870s, Murtaugh licensed Isaac Richards of Philadelphia to build his patented dumbwaiters. In 1875, Manufacturer and Builder reported Richards also specialized in the manufacture of “invalid safety elevators” that combined “ease of working and security with the utmost durability.”[2] Murtaugh and Richards continued to build invalid lifts throughout the remainder of the 19th century and were quickly joined by numerous competitors.

By the early 1880s, three Boston firms were advertising invalid lifts: Felix P. Canfield (balanced hand elevators), Zerah Wile (passenger and freight elevators, hand hoists, etc.) and Elias Brewer (elevators).[3] While, like Richards, Wile and Brewer claimed invalid elevators were a “specialty,” all three Boston firms differed in that they manufactured passenger and freight elevators, not dumbwaiters. Thus, the invalid lift was perceived as a standard elevator type. This did not, however, mean dumbwaiter manufacturers ceased building them. In 1888, Butler Hardware Co. of NYC reported it was the “sole manufacturer” of Cannon and Emerick dumbwaiters, with the latter easily “adapted for invalid lifts. . . in flats and private dwellings.”[4]

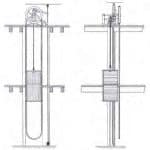

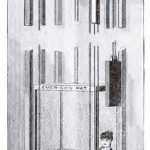

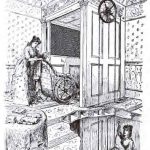

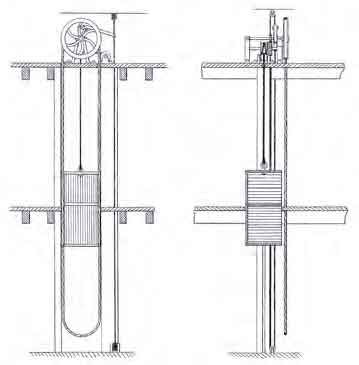

The Emerick invalid lift derived from Garrett M. Emerick’s design: “Dumb-Waiter,” U.S. Patent No. 375,146 (December 20, 1887). While his patent does not mention the application of this technology to passenger use, this did not prevent Butler Hardware from using it as the basis for a hand-powered passenger elevator. In its 1890 catalog, the company published one of the first drawings of an invalid lift, which, when compared with Emerick’s patent drawings and an engraving of an Emerick dumbwaiter, reveals a simple technological transformation that primarily involved replacing the dumbwaiter cupboard with a passenger car (Figures 1-3). The invalid lift image also attempts to highlight the supposed ease with which a passenger could transport themselves. However, the prospect that a seated disabled person could power the lift — using only one hand — raises numerous questions. This suggests the lift employed a perfectly counterbalanced system with extremely efficient gearing and an effective automatic braking mechanism. This also implies a system that moved very, very slowly.

In 1891, Storm Manufacturing Co. of Newark, New Jersey, published a drawing of its invalid lift that expands our understanding of this type (Figure 4). The image accompanied an article titled “A Help for the Infirm,” which described the benefits of these lifts:

“Nothing of the many modern appliances that are being put into the new houses of today is a source of greater convenience and more comfort than an invalid lift, when properly constructed. Not only are they of inestimable value in a household where there are one or more invalids to go up and down stairs, but they are also of great convenience in every well-equipped house, being easier and quicker than walking.”[5]

The article also provided information on the car design and operation:

“The cars of these machines are handsomely made, being paneled 4 ft. high with bronzed wire work on top of the panels. And, they are made in different sizes to suit the various places where it is desirable to place them and can be run any number of stories. They can be operated by the person on the car or by an attendant on either floor to which they go. Being operated by hand, they are not expensive and can, therefore, be used in many places where power elevators would be impracticable.”[5]

The article’s unknown author reported Storm had “made hundreds” of these lifts.

The design of the Storm invalid lift followed the pattern established by Butler Hardware in that it also derived from a patented system. In this case, the patents concerned hand-powered elevators, and the designer was Abraham S. Humphrey: “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 393,831 (December 4, 1888) and U.S. Patent 434,599 (August 19, 1890). Although the 1891 drawing conceals the gearing and brake, the placement of the hand and brake ropes (the latter being pulled by the woman on the lower floor) are consistent with Humphrey’s patent drawings. (Compare Figures 4 and 5.) This depiction of an invalid lift does not rely on the disabled person to transport themselves. However, the location of the individual who, presumably, will power the lift is somewhat odd. Their presence on the floor below where the lift is being accessed seems to indicate that a great deal of shouting was needed to coordinate the lift’s movement. It is also of interest that all those depicted in the invalid lift drawings examined thus far are women. This may represent an effort to reinforce the domestic character of this technology and the idea the elevators were easy to use.

The production of invalid lifts continued to expand throughout the 1890s with new companies steadily entering the marketplace. In Chicago, Cannon’s Dumb Waiter & Hand Elevator Co. and J.W. Reedy Elevator Manufacturing Co. advertised invalid lifts. In Philadelphia, McCalvey Elevator Works manufactured “Invalid Safety Elevators.” In Boston, George H. Davis described himself as a “manufacturer of hand elevators, carriage hoists, invalid lifts, dumb waiters, hatch covers and doors for elevators.”[6]

Storm continued the production of invalid lifts during this period. They were featured in a second illustrated article published in 1904 with an image of a revised version of the 1891 drawing that revealed the gearing and brake at the top of the shaft (Figure 6). The description of the lift and its perceived benefits paralleled the earlier account:

“This very desirable addition to dwellings, where proper care and attention are needed to be given to the afflicted, has been demanded in common with other conveniences in household economy so necessary for perfect comfort. The machinery for this special Invalid Lift is their Improved Humphrey Hand Elevator. The car is built of hard wood, handsomely paneled and finished with brass grille work and makes the most complete, easiest working and safest Invalid Lift that could be desired. This machine is equipped with two cables or with safety attachment as desired. Directions are furnished for erecting, or prices will be quoted for them to be erected in any part of the country.”[7]

The presence of the wheelchair in both Storm invalid lift images was clearly intended to emphasize the purpose of the system: to serve persons with disabilities.

The U.S. was not alone in the production of invalid lifts during the 19th century. In 1880, Clark, Bunnett & Co. of London advertised “Bunnett’s safety hoists” and “invalid lifts.”[8] These were joined by Pickerings in 1889 (passenger and invalid lifts) and Lift and Hoist Co. of London in 1896 (invalid lifts).[9] Unfortunately, no images of these lifts have been discovered. Their presence outside the U.S. and England also remains an unexplored topic. The conclusion of this article will follow the history of invalid lifts in the U.S. into the first decades of the 20th century.

- Figure 1: Front and side elevations of Emerick Dumbwaiter, derived from Garrett M. Emerick’s “Dumb-Waiter” patent

- Figure 2: Emerick Dumbwaiter with hinged shelf, “Emerick Dumbwaiter,” Carpentry and Building (February 1888).

- Figure 3: Emerick Invalid Lift. Butler Hardware Co. Catalog (1890).

- Figure 4: Storm Manufacturing Co. Invalid Lift[5]

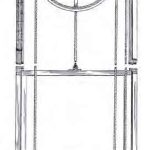

- Figure 5: Front elevation of Humphrey Dumbwaiter, derived from Abraham S. Humphrey’s “Elevator” patent

- Figure 6: Storm Manufacturing Co. Invalid Lift[7

References

[1] “Murtaugh’s Celebrated Dumbwaiters,” New York Herald (April 3, 1869).

[2] “Miscellaneous and Advertising,” Manufacturer and Builder (March 1875).

[3] Boston City Directory (1881, 1883 and 1885).

[4] Butler Hardware Co. advertisement, Carpentry and Building (December 1888).

[5] “A Help for the Infirm,” Scientific American Architects and Builders Ed.

(September 1891).

[6] Chicago Business Directory (1891 and 1894), Boston City Directory (1894), Cambridge Directory (1895) and Boyd’s Co-partnership and Residence Business Directory of Philadelphia City (1895).

[7] “Special Invalid Lift,” Hardware ( June 10, 1904).

[8] Clark, Bunnett & Co. advertisement, London Daily News (November 27, 1880)

[9] Pickerings’ advertisement, Northeastern Daily Gazette, North Yorkshire

( June 15, 1889) and Lift and Hoist Company advertisement, Academy Architecture (1896).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.