The Levytator: A New Innovation That Could Change Escalators as We Know Them

Jan 1, 2011

This paper discusses a new innovation that represents the first significant change in elevator design in more than 100 years.

by Don Sadler, EW Correspondent

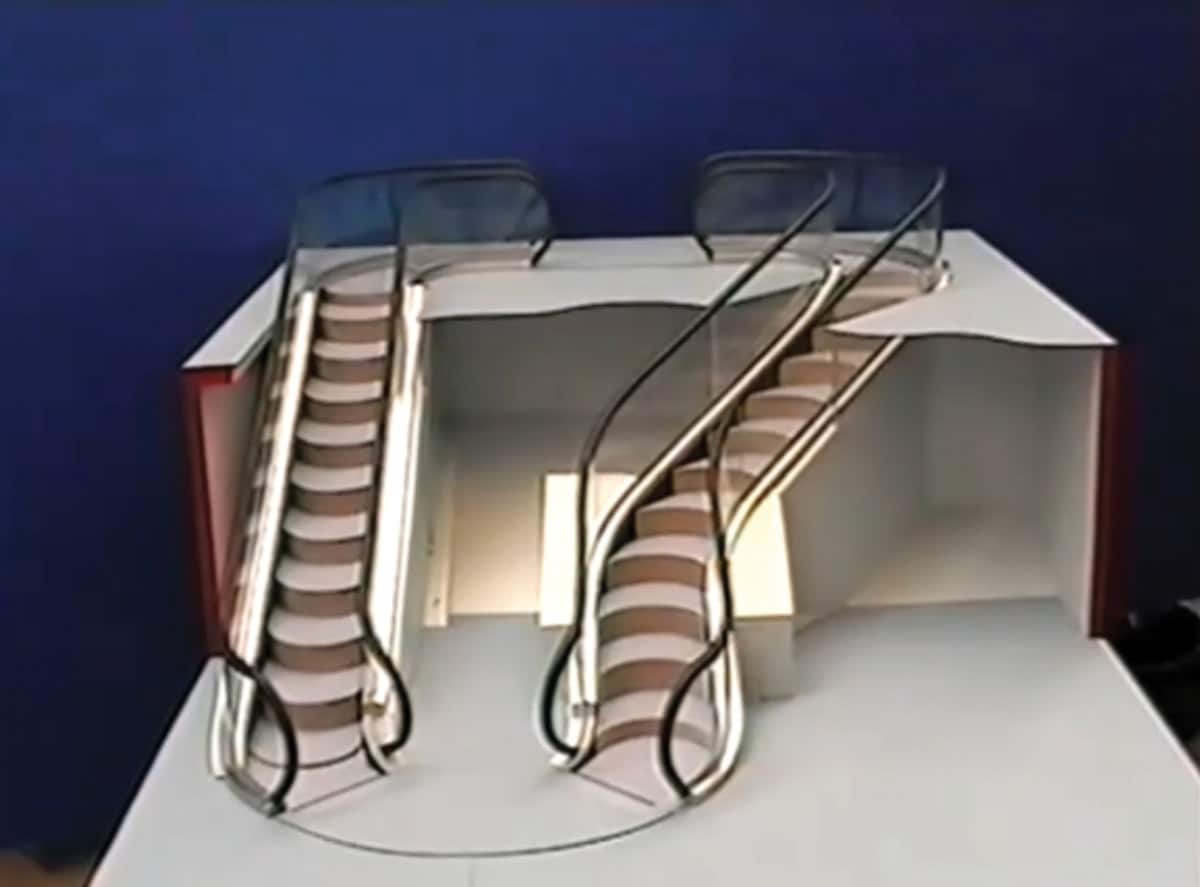

What’s a common mechanical device found in all kinds of buildings all over the world today that is essentially unchanged since it was first invented more than 100 years ago? If you guessed the escalator, you’re right. However, a new innovation has recently been patented that represents one of the first significant changes in design since escalators were invented in the late 19th century. It’s called the Levytator. It was patented in 2010 by Jack Levy, an emeritus professor of Mechanical Engineering at City University London.

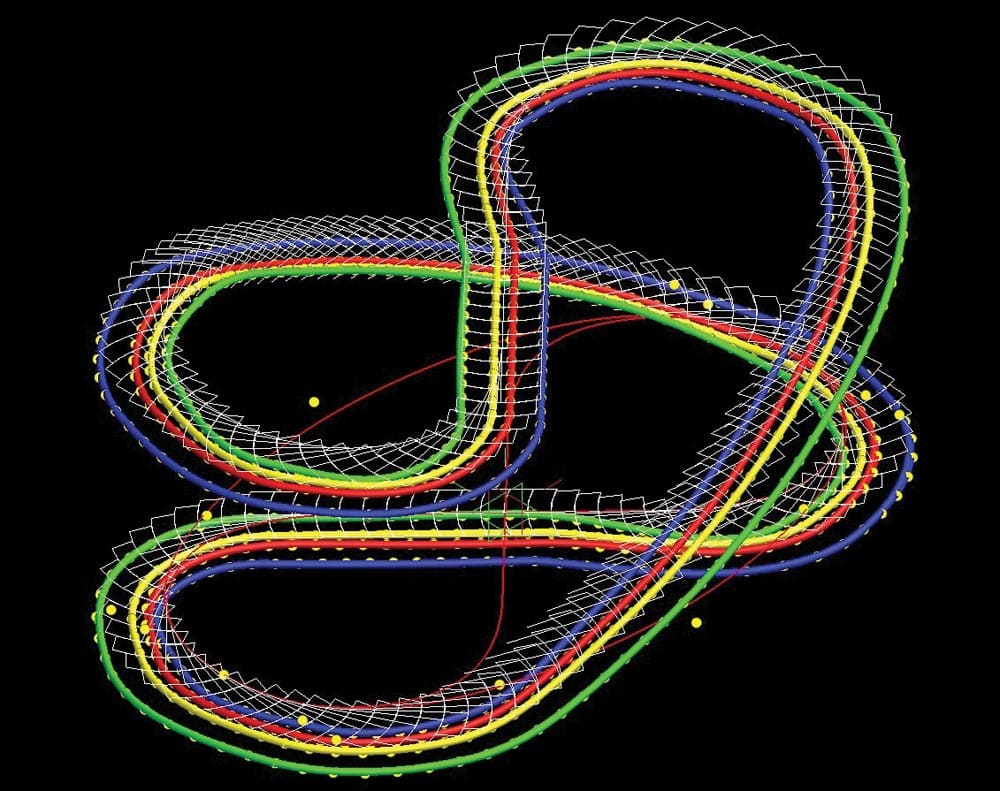

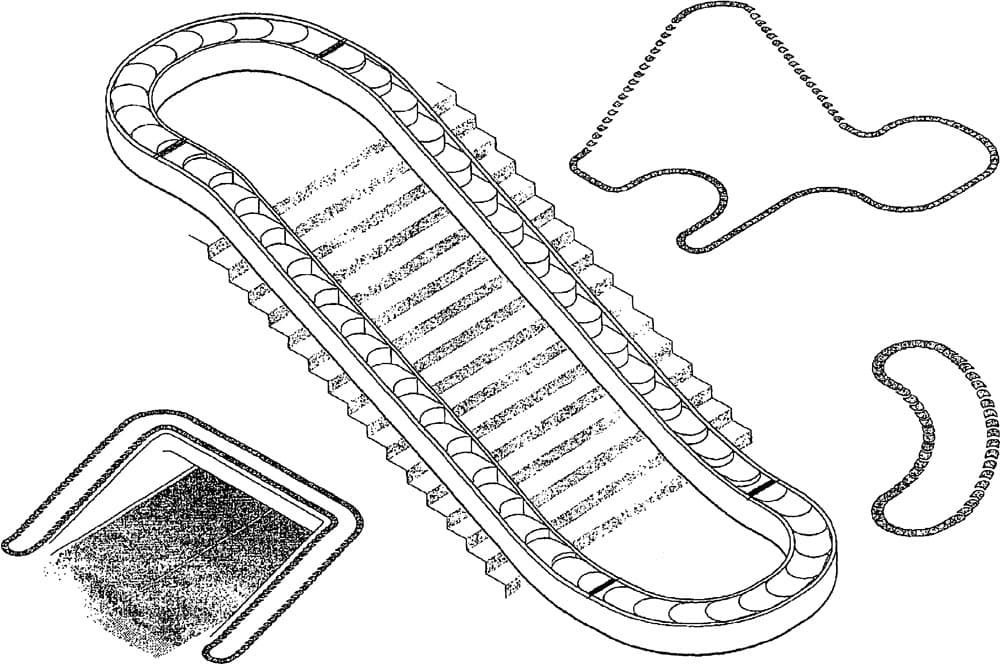

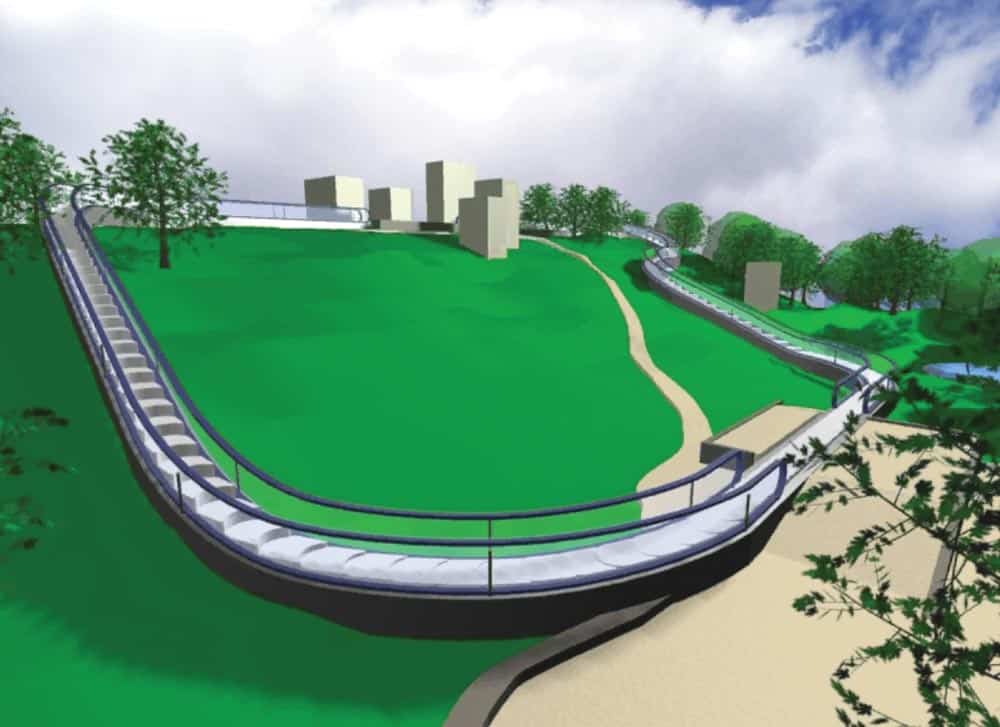

With traditional escalator designs, redundant steps move underneath those in use, which significantly limits design possibilities. However, the Levytator utilizes a continuous loop of curved, interlocking steps that can follow any path: up, down, flat, straight or curved, all while supporting passengers.

According to Levy, all escalators have relied on the same basic design since 1897. This is also one of the first times anyone has gone back to the drawing board and thought about how an escalator could be built from the ground up using today’s technology. This design breakthrough will enable architects to create escalators in virtually any shape they desire, including freeform curves.

New Possibilities

Levy adds:

“The need to move people in a fast, efficient way between floors has dictated a set of straight lines in atriums and open spaces. But what if these could follow the design of the open space or could curve? This opens up a whole new set of possibilities for architects.”

For example, imagine putting a Levytator configured as a DNA double helix in a building for a bioscience organization, or using a Levytator to carry guests safely along on a moving theme-park tour.

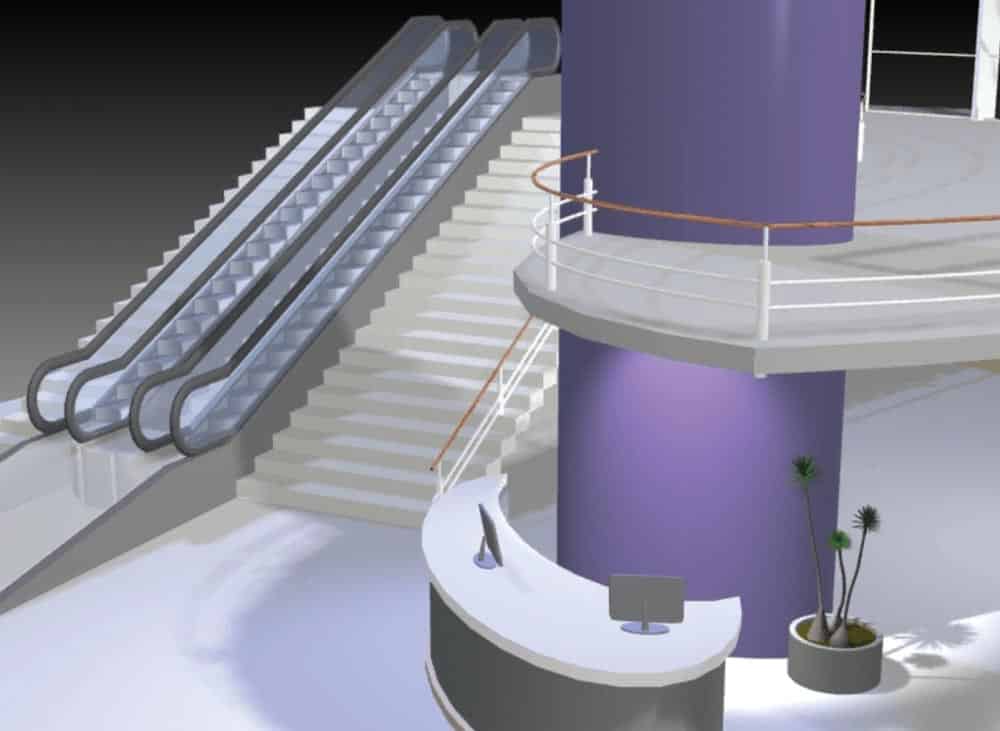

According to David Chan, director of City University’s Centre for Information Leadership and a consultant to the project, the Levytator opens up new possibilities for architects in various types of building designs. Since it doesn’t require excavation for the return path, it can be installed on top of existing staircases with minimal disruption.

The Levytator has been patented in the U.K., Europe, the U.S. and China, and Chan says that City University London is actively seeking strategic partnerships with architects and manufacturers to take the Levytator to market. Chan also claims that since it can carry twice as many people per step as a traditional escalator (and at a comparable price), it will be an attractive financial proposition.

Meeting Technical Challenges

Surprisingly, Levy’s background and experience are not in the escalator or elevator industries, but rather in industrial manufacturing and design. He started in the aircraft industry and has worked on a wide range of design and technology issues as head of the Mechanical Engineering department at City University London.

Levy has spent many years traveling on London’s underground escalators, leading him to wonder whether it was possible to design a multi-curving escalator model. “There were two primary technical challenges following the initial concept,” according to Levy.

He adds:

“The first was the design of a joint that would allow lateral, as well as vertical movement between the steps, and the second was the closing of the gap (for safety reasons) between the curved stationary wall and straight side of the moving step. The solutions to both of these problems are included in the patent.”

Lars Hesselgren, research director for PLP/Architecture in London, one of the architecture firms that is in discussions with City University about potential commercial applications for the Levytator, says he started doing some design work toward a curved escalator a few years ago, but put it in a drawer, since his firm isn’t a manufacturer.

Hesselgren commented:

“Then, when the Levytator demo video popped up on YouTube, people started asking me if it [were] my invention. Obviously, Jack and I were thinking the same thing. We want to work with the developers of the Levytator to make this happen, because we have very definite ideas about how we can use it. We think the Levytator has the potential to change the escalator world as we know it.”

Lower Cost, Greater Flexibility

Hesselgren believes the Levytator will enable developers and architects to build escalators less expensively and with more flexibility. Entire buildings are often designed around escalator runs, which is limiting. Currently, escalators cannot be used as a means of emergency escape, but the Levytator might change that.

Hesselgren also sees the Levytator as a creative way for shopping-mall owners and developers to draw more shoppers to the upper floors. Since the Levytator could get people higher more easily and in a more efficient way, it could have some appeal to mall developers.

According to Levy, the cost to install the Levytator will be similar to that of a traditional escalator. But since the Levytator can carry twice as many people per step, the cost per usable step is cut in half. Also, all maintenance work and inspections can be carried out from above ground, which will reduce downtime and operational costs.

Hesselgren believes that above-ground instead of underground maintenance could make the Levytator revolutionary for underground transportation. Escalators that get passengers down to subway systems can be shut down for maintenance for months, but the Levytator could potentially cut this time, effort and cost in half. Underground systems like the new Crossrail project in London are designed on the premise that escalators

have to be straight. Hesselgren believes that a curved escalator system like the Levytator could reduce costs considerably.

It’s Not a Spiral Escalator

If you’re thinking you’ve seen spiral or free-form escalators before, perhaps you have. Spiral escalator designs have been patented in the past – some as long ago as the early 20th century. Mitsubishi is among the manufacturers that produce spiral escalators and has installed about 100 around the world since 1986 (or only about four a year), mostly in Asia.

Dave Turner, U.S. elevator and escalator consultant is familiar with the spiral escalator design and notes:

“There has been limited marketplace acceptance of spiral escalators due to the high cost of manufacturing, installation and maintenance.”

However, Chan explains that the Levytator is much more than a spiral escalator, adding: Continued

“The key difference between the Levytator and the Mitsubishi spiral escalator is that the latter must follow a circular path with a fixed radius. With the Levytator, each step can move in a straight path, go around a bend of one radius, then go around a bend of another radius. In other words, the Levytator is configurable in [several] different shapes.”

Levy and Chan both acknowledge the challenges in gaining market acceptance and penetration of a new technology like the Levytator. After hitting some roadblocks in their initial efforts to market the Levytator to manufacturers, they took a different track, focusing instead on marketing to surrogates like architects, scheme developers and even consumers.

The Levytator video on YouTube, for example, had been viewed more than 226,000 times as of November 2010, and according to Chan, “If we can just get people interested, they’ll come to us, and this is exactly what’s happening.”

Levy believes that once about six Levytators are installed, all barriers will disappear, and it will expand opportunities for architects to design forms that are not linear. One of the main issues is the development cost of the prototype concept needs to engineered.

Safety is Paramount

Of course, the Levytator must take into account passenger safety, “and there are a host of safety issues that must be addressed with the design of the Levytator,” Turner adds.

Jim Marcusky, elevator and escalator consultant concurs:

“From an engineering perspective, the first thing I usually try to do is figure out what can go wrong with something. So I would want to know how the Levytator would operate in a heavy-duty environment, and, ‘Will it be safe?’ I think proper alignment and assembly of the track system would also be a challenge. Also, can tolerances be maintained, and what about vibrations and ride quality? However, I can see where architects would love this, and its potential is unlimited if it works like the designers believe it will.”

Looking ahead, beyond the early adopter phase, Levy believes the Levytator could expand the total elevator/ escalator market by 20%, since it can be used where conventional elevators and moving walks cannot be installed. It may replace some elevators with an attractive total cost of ownership characteristics.

Turner also believes that the Levytator has potential if all the pieces come together and the challenges can be overcome:

“If Levy is successful with his design, the applications are limited only by the imagination of the architect or building designer and the cost of the conveyance.”

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.