This article tries to answer some nagging questions regarding company compliance with consensus standards.

by Paul Waters

Over the past two years or so, I have received many questions from companies about compliance with so-called “consensus standards” such as NFPA 70E, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA)’s standard for electrical safety in the workplace. Companies performing elevator repair or construction have been particularly concerned about NFPA 70E. Their questions generally include, “Can OSHA cite me for not following NFPA 70E?” That is a good question with no easy answer.

The original NFPA 70E was published in 1979 to address certain perceived problems in OSHA’s electrical safety standards, such as those in construction (Subpart K, 29 C.F.R. § 1926.400, et seq.) or general industry (Subpart S, 29 C.F.R. § 1910.301, et seq.). One major reason for NFPA 70E was to provide a speedier and more-streamlined guide to safe work practices that could not be matched by the procedures required of OSHA in Section 6(b) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) to amend its standards. Another reason was to provide an explanation of safe work practices that average employers could understand and apply in their workplaces.

By 2004, NFPA 70E had expanded in scope to cover topics such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and safe work practices in a level of detail far exceeding OSHA’s electrical safe work practices standards. By this time, the sole reason for NFPA 70E was to set forth the latest in electrical work practices to guide OSHA, employers and employees, with topics such as electrical system design or installation being removed and left to the National Electrical Code.

Then, in mid 2008, the latest NFPA 70E was released, with an effective date of September 5, 2008. Even prior to that, though, my phone began ringing as companies asked urgently what it meant and what force of law it would have. The new NFPA 70E contained significant revisions to prior versions, including provisions setting forth calculations of such things as an arc flash protection boundary for workers, the contents of electrical safety programs, procedures for evaluating hazards/risk of electrical work and analyses on the permissibility and practices for energized electrical work. Employers committed (and continue to expend) significant resources trying to ascertain what is required of them under the new standard.

‘‘Can OSHA cite me for not following NFPA 70E?’’

The first obvious question concerns why any employer should be concerned with NFPA 70E. It is important to note that, as a “voluntary consensus standard,” the NFPA 70E has no independent legal force; it is “voluntary.” It is not an OSHA standard, nor has it been adopted by OSHA through the proceedings set forth in Section 6(b) of the OSH Act to make it law. Thus, on one level, it is only a “guide” for employers for making decisions about safe work practices, programs and PPE. An employer cannot be cited by OSHA merely because it does not follow the provisions of a consensus standard like NFPA 70E.

Moreover, the process for creating a “voluntary consensus standard” is significantly different than the process for creating a legally binding OSHA standard. For example, parties like vendors of machinery and PPE to abate the hazards covered by the consensus have a significant role in crafting the standard’s terms. Many would argue that such parties have a significant conflict of interest. Without the mechanisms that exist in an OSHA rulemaking proceeding to protect the regulated community, requirements of consensus standards may overstate potential hazards and require measures that many industries consider overkill based on their experience with actual working conditions.

The whole answer concerning a consensus standard’s legal force, however, is not that simple. Although the NFPA 70E is not law, OSHA can use provisions of the NFPA 70E to support citations of OSHA regulations and the General Duty Clause of the OSH Act. For example, certain OSHA electrical PPE standards are written in very general terms. Section 1910.132(a) requires PPE “when necessary by reason of hazards.” Likewise, § 1910.132(c) requires equipment to “be of safe design and construction for the work performed,” while § 1910.132(d) requires that employers provide equipment that will “protect the affected employee from the [identified] hazards.”

These general standards do not specify which equipment to use under particular circumstances, allowing employers flexibility in determining what is appropriate based on working conditions. However, OSHA can cite an employer for not providing suitable PPE for the work being performed and use the provisions of NFPA 70E as evidence to support that violation. Similarly, in a case where a specific standard does not apply, OSHA could use NFPA 70E in a citation for a violation of the General Duty Clause, Section 5(a)(1) of the OSH Act. There, NFPA 70E is used as evidence that the alleged hazardous condition was “recognized” by industry and that a feasible method of controlling the hazard existed. OSHA has taken those approaches with NFPA 70E to issue multiple citations for violations of the electrical safe work practices, training and PPE standards to the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) over the last year, amounting to hundreds of thousands of U.S. dollars.

Therefore, given that OSHA can utilize NFPA 70E to support citations involving electrical safe work practices, PPE and training, a reasonable employer cannot blithely conclude that the standard is hogwash and ignore it simply because it does not seem relevant to the employer’s work. This is especially so when given OSHA’s recent emphasis on using its egregious or “instance-by-instance” penalties for violations in areas such as PPE or training. An employer of even modest size faced with penalties based on each instance of an employee who allegedly did not receive proper PPE or training could quickly see proposed penalties such as USPS has experienced.

A repeated concern voiced by employers, especially in the elevator/escalator industry, was that the NFPA 70E’s apparent sweeping application could mean millions of dollars in purchases of new PPE. By applying the NFPA’s key tables, such as Table 130.2(c) (“Approach Boundaries to Live Parts for Shock Protection”) and Table 130.7(c) (9)(a) (“Hazard/Risk Category Classification”), work tasks that had previously been thought to present only minimal risks now seem to clearly fall into elevated hazard/risk categories. Then, by applying tables like 130.7(c)(10) (“Protective Clothing and PPE Matrix”) and 130.7(c)(11) (“Protective Clothing Characteristics”), this work appeared to require specialized PPE that had not previously been considered necessary. Quite literally, work by an adjuster on an energized control panel would require an outfit that would make him look like Neil Armstrong on his moonwalk.

‘‘A repeated concern voiced by employers, especially in the elevator/escalator industry, was that the NFPA 70E’s apparent sweeping application could mean millions of dollars in purchases of new PPE.’’

It is important to note that these concerns were not from employers looking to shirk their responsibility to protect workers – they were already spending millions of U.S. dollars on various types of PPE nationwide, and they consistently put safety first and tried their best to protect their workers. Elevator companies, for example, have had employees performing certain tasks on control panels repeatedly and for decades, with virtually no incidents. Suddenly, because of the guidelines in the new NFPA 70E, the industry is being told that those tasks were potentially far more hazardous than extensive field experience has shown them to be.

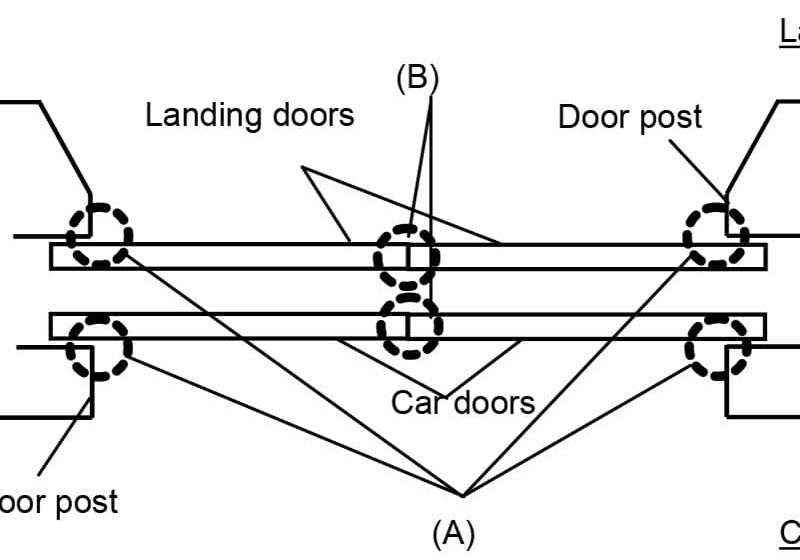

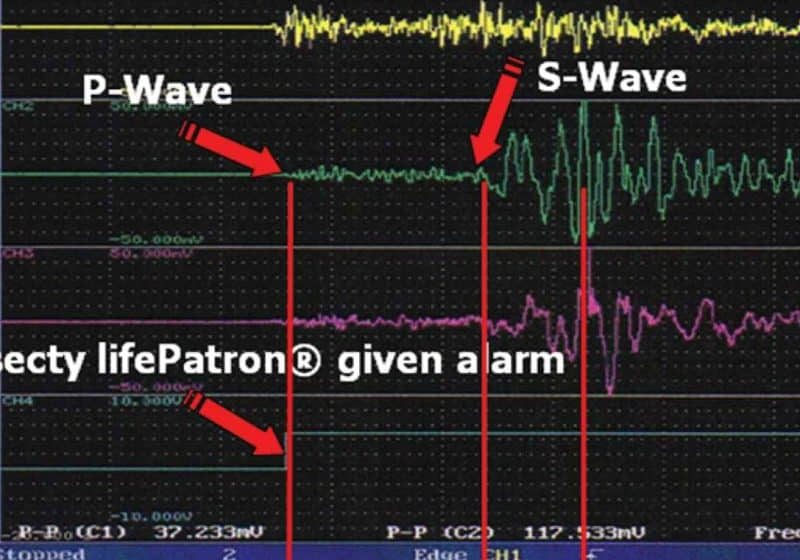

Other issues have shown the difficulty of applying broad consensus standards like NFPA 70E in particular settings. For example, an elevator company servicing equipment at a host employer may have employees doing diagnostic work on energized control panels. There may be multiple employees doing such work each day, with some employees doing service calls at multiple locations in a single day, with little to no advance notice. Most panels would contain parts operating at less than 240V, while others might have lines into the panel greater than 240V, but reduced to 240V or less in the area of the box where work was to occur (but still putting the employee within the “arc flash boundary” for the higher-voltage part, assuming, without calculating, that it is 48 inches). There could be multiple transformers serving circuits, as well, which would not be known beforehand. Under NFPA

70E, such conditions could be construed as requiring a detailed “arc flash hazard analysis” for each instance of service and piece of equipment, despite the fact that in decades of diagnostic work industry wide, no arc flash injury had occurred.

In addition, NFPA 70E tables meant to provide a “quick and easy” decision tree to avoid an “arc flash hazard analysis” technically may not be used, because their use is conditioned upon knowing such things as short-circuit current and fault clearing times for the equipment serviced. Thus, what previously had been routine work thought to present no “extraordinary” electrical hazards (where PPE could consist of appropriate gloves, boots, safety glasses, natural-fiber pants and long-sleeve shirts) is elevated to work requiring higher-level math skills for an arc flash hazard analysis, an arc flash suit hood or balaclava and face shield, coveralls with an arc rating of at least eight, and the like. This would all be in a situation where no previous serious incidents had occurred.

The foregoing is a simplification, but not by much. Obviously, the intent of consensus safety standards like NFPA 70E is to prevent accidents before they occur, so the mere fact that an industry has not had an accident does not mean a provision in a standard is not needed or not useful. Industry experience, however, is important to illustrate the difficulty of giving consensus standards the force of law.

‘‘Thus, what previously had been routine work thought to present no ‘extraordinary’ electrical hazards is elevated to work requiring higher-level math skills for

an arc flash hazard analysis.’’

Unfortunately, a consensus safety standard meant to be broad in application cannot help but sometimes be over-inclusive by its nature. This is partly why the procedures for the way OSHA makes rules exist, so as to minimize nasty surprises on the regulated community and provide an opportunity to have the rule reflect industry and worker concerns. Here, given that OSHA’s use of NFPA 70E will be to show what allegedly is “necessary” to protect against “identified” hazards, an employer could justifiably assert that its lengthy experience and lack of incidents in its industry proved that its PPE was perfectly adequate, despite not being what was mandated by the NFPA 70E. Unfortunately, of course, such an argument most likely would come during a battle with OSHA (after violations have issued), with OSHA waving NFPA 70E before the judge.

Paul Waters represents employers nationwide in enforcement and rulemaking proceedings before the federal Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and state OSHAs. He also represents clients in civil litigation, ranging from whistleblower claims to employment and housing discrimination. Waters has handled multiple trials and numerous appeals in state and federal courts concerning related cases. He regularly speaks on these issues and has been a panelist at the annual Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission’s judge’s conference. He has also participated in industry panels concerning environmental safety and health issues in the field of nanotechnology. He received his JD from Boston College Law School in 1994.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.