The Ritter Controller and Door Locking Device for Elevators

Sep 1, 2018

The story of an amateur’s limited success in the development, manufacture and selling of elevator components in the early 20th century

Nineteenth and early 20th-century patent records include hundreds of designs for elevator door safeties. These designs include both overly simplistic and incredibly complex solutions. Many of these schemes shared a common characteristic: they existed solely in the mind of their inventors and within their respective patents. In other words, the proposed safety was never commercially produced or tested in a “real-world setting.” Many of the inventors of these devices also shared a common characteristic: they often had no connection to the elevator industry and, thus, regardless of their personal engineering or technical skills, operated as “amateur” elevator safety designers. There were, however, a few instances where one of these seemingly untenable but patented designs was manufactured, marketed and unleashed on an unsuspecting world.

In July 1905, Isaac B. Ritter, owner of Ritter Machine Co. in Philadelphia, filed his first application for an elevator-related patent. This was followed by a second application in March 1906. Both patents, each named “Safety Device for Elevators,” concerned the design of an elevator safety: U.S. Patent No. 809,076 ( January 2, 1906) and U.S. Patent No. 838,213 (December 11, 1906).

While the descriptive language required in patents occasionally results in somewhat inelegant technical descriptions, Ritter’s summaries of his design represent particularly tortured examples of the English language:

“My invention as generally stated consists in the employment of locking-levers at the doors of the hatchway for locking the doors and mechanism upon the car to engage said levers to unlock the doors, also a lever which is thrown into action when said door is open to lock the operating mechanism of the car, together with various novel features of construction and organizations of parts.”[1]

Expressed more simply: the safety ensured that the shaft door could not be opened unless the car was at the landing, and that the car could not move from the landing until the shaft door was closed.

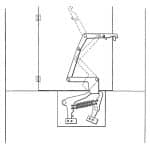

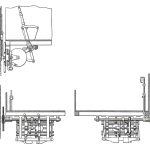

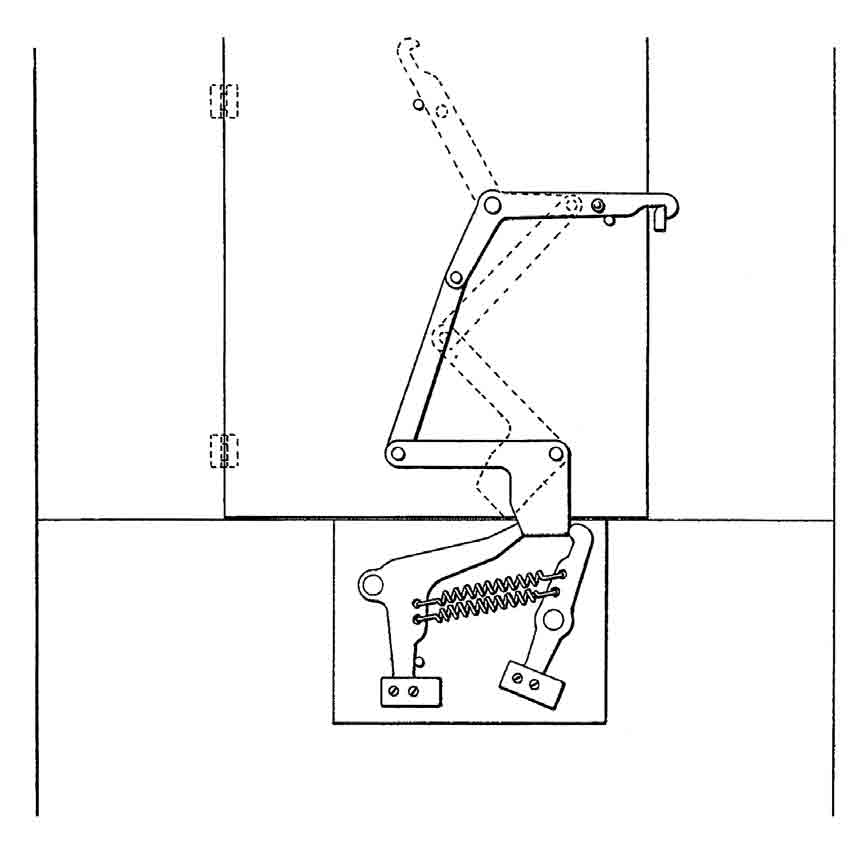

Ritter’s technical solution was almost as complex as his explanation. The lock locking mechanism, which would be released by the presence of the car, was the simplest component. A plate mounted below the door held a bell crank lever, which, when released, allowed the door locking levers to rotate such that the operator could open the door (Figure 1). The function of the lever opposite the bell crank lever is less obvious. It was intended to lock the car operating mechanism such that the car could not move while the door was open. This relatively simple mechanical operation was made possible by a complex mechanism located beneath the car (Figure 2). It featured a series of cams that engaged the shaft door levers. It was activated when the operator pulled the control lever to stop the car.

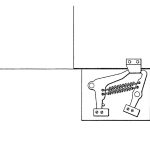

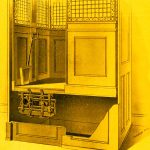

At this point in the history of similar overdesigned safety devices, the story would normally conclude, as the device appears to be too complicated to offer users a viable technical solution. However, in this instance, the inventor’s faith in his design, coupled with his possessing the means to manufacture the device, led to the production of the “Ritter Controller and Door Locking Device for Elevators.” Ritter’s marketing campaign included an illustrated catalog that extolled the technological virtues of his invention. The catalog drawings reveal that some, albeit limited, design development continued after the patent phase. One change was a simplification of the door lock. The mechanism was reduced to a simple bracket mounted on the bottom of the door that was engaged by the bell crank and straight levers (compare Figures 1 and 3). However, the core of the design, the mechanism located under the car, retained its complex mechanical scheme (Figures 4 and 5).

The catalog included a detailed description of the safety’s operation. When the car approached a destination landing and the operator moved the control lever (or wheel) to the stop position, this action caused the safety gear below the car to shift forward and engage the bell crank lever, unlocking the shaft door. When the operator slid the door open, this released the straight lever opposite the bell crank lever. This action engaged the car control lever such that the car could not be moved. Once the passengers had exited and entered, the operator would slide the shaft door closed, an action that simultaneously released the car operating mechanism and locked the door. Ritter summarized the key features of his safety as follows:

- The locking apparatus of each landing acts independently.

- The doors of the shaft are locked from the inside and cannot be opened until the controller is in a “stop” position and the car is brought to a stop within 3 in. above or below the landing.

- The opening of the door locks the controller in the “stop” position.

- The car cannot be started until the door is closed, whereby the operator is prevented from starting the elevator while passengers are entering or leaving the car.

- The car can be run from the top to the bottom of the shaft without touching any of the mechanism of the landings, unless a stop is desired at a given landing.

- The device is attached to the regular controlling mechanism of the car, or it may be operated by a push button in the floor of the car.

- The device may be used on hydraulic, plunger or electric elevators with hand wheel or lever-controlled mechanism.

- This device takes up very little room under the floor of the car and can, therefore, be installed where there is only a shallow pit (a minimum of 18 in. in depth).[3]

Ritter also reminded potential purchasers of the importance of passenger safety (and, thus, the rationale behind his safety) in his catalog copy:

“Every elevator should be equipped with a Controller and Door Locking Device, because 90% of all elevator accidents result from persons making a hasty entrance or exit while the operator is starting the car, before the door is closed.”[2]

His confidence in his design — and his manufacturing skills — was reflected in his assurance of product quality:

“The Ritter Machine Co. guarantees its work for two years to the extent of making necessary repairs to devices installed within 100 mi. of Philadelphia. On devices at further distances, we will furnish all repair parts needed free of charge for two years.”[2]

Of course, patents and a published catalog do not serve as indications of commercial success; they only speak to invention and marketing. Fortunately, the catalog that inspired this investigation, which appears to date from 1915, included a list of buildings where Ritter’s safety was “installed and could be inspected.” The list included 19 buildings: 14 in Philadelphia; three in other Pennsylvania cities (Pittsburgh, Germantown and Scranton); and one each in Wilmington, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. In addition to identifying the individual buildings, Ritter also reported on the extent of his safety’s use: it was installed beneath a total of 36 elevator cars and on 337 elevator doors. The largest installation was in the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia: nine elevators (built by Standard Plunger Elevator Co.), which engaged 162 shaft doors.

The awareness of these installations raises a question that often goes unanswered: how well did the safety work? In this case, one (very brief ) review of its operation exists. In 1915, the Building Managers’ Association of Baltimore appointed a committee charged with investigating “the elevator door locking devices used in buildings in Philadelphia.”[3] The committee examined the safeties installed in the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel and reported that, in their opinion, “these devices are dangerous to passengers, on account of projection in hatchway.”[3] They also noted that the safeties were “inoperative on several floors, particularly on the first floor.”[3] The context for this review is also important.

The committee’s investigation of elevator door safeties was prompted by a proposed new ordinance that would require all elevators in Baltimore to “be equipped with a device which is supposed to hold the elevator at the door until the door leading into the elevator shaft is shut and securely fastened.”[3] The association claimed that, to “install patented devices,” would cost owners “at least US$20 per door for each and every door opening into your elevator shafts.”[3] The association believed that this cost was too high, particularly for safeties that were typically “both ineffective and unsafe.”[3]

The invention and marketing of the Ritter Controller and Door Locking Device for Elevators was not, however, Ritter’s only attempt at designing elevator safeties. In 1907, he filed two more applications for patents that were issued in 1909 and 1913:

“Automatic Device for Bringing Hydraulic-Elevator Cars to the Floor-Level,” U.S. Patent No. 909,675 ( January 12, 1909) and “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 1,066,052 ( July 1, 1913).

The development of an effective automatic leveling device was one of the holy grails of the early 20th century. Ritter described this invention as providing “a means for automatically bringing the elevator car to the floor level when the car is stopped within 8 in. of the floor and also for preventing the car moving away from the floor level due to the leaking of the valves.”[4]

The patent with the somewhat ambiguous title of “Elevator” concerned an overly complex system designed to prevent the car from falling “should the supporting means break.”[5] Unlike his previous efforts, there is no evidence that Ritter sought to manufacture elevators that employed the designs found in these patents. His final elevator patent — “Hydraulic Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 1,261,624 (April 2, 1918) — concerned an improvement to his automatic leveling device. This appears to have been his most successful design effort, at least in terms of its reception by the elevator industry, as it was assigned to Otis. Unfortunately, the nature of his business relationship with Otis is unknown at this time, and his participation in the world of vertical transportation appears to have ended around 1918.

- Figure 1: Ritter door unlocking mechanism; drawing derived from image found in “Safety Device for Elevators,” U.S. Patent No. 838,213 (December 11, 1906).

- Figure 2: Ritter under-the-car safety mechanism; drawing derived from images found in “Safety Device for Elevators.”

- Figure 3: Ritter modified door unlocking mechanism; drawing derived from image found in “Safety Device for Elevators.”

- Figure 4: Ritter under-the-car safety mechanism[2]

- Figure 5: Ritter under-the-car safety mechanism[2]

References

[1] Isaac Ritter, “Safety Device for Elevators,” U.S. Patent No. 809,076 ( January 2, 1906).

[2] “The Ritter Controller and Door Locking Device for Elevators,” Philadelphia: Ritter Machine Co. (circa 1915).

[3] “A Protest Against Compulsory Installation of So-Called Elevator Safety Devices,” The Hotel Monthly, Vol. 23 (February 1915).

[4] Ritter, “Automatic Device for Bringing Hydraulic-Elevator Cars to the Floor-Level,” U.S. Patent No. 909,675 ( January 12, 1909).

[5] Ritter, “Elevator,” U.S. Patent No. 1,066,052 ( July 1, 1913).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.