The Salem Elevator Works (Part Two)

Nov 1, 2022

Conclusion looks at the success, expansion and transformation of Charles F. Curwen’s company.

Part one (The Salem Elevator Works (Part One)) of this two-part article traced the story of Salem Elevator Works in Salem, Massachusetts, (established as the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop) from its founding in March 1870 to December 1890. This 20-year period witnessed a critical leadership transition with Charles F. Curwen (1853-1909) assuming the role of proprietor in 1879. He steadily increased the company’s production of elevators until they became its leading product. This conclusion will address Curwen’s success in establishing his company as the leading supplier of freight elevators to the textile industry, the gradual expansion of his product line and the transformation of Salem Foundry and Machine Shop into Salem Elevator Works.

Throughout much of the 1890s, Curwen continued a strategy he had begun to employ in the mid-1880s, in which he regularly provided promotional materials and press releases to a variety of industry and engineering publications. This material often included reports of recent installations and information on the company’s business outlook. A July 1891 article characterized the company as “builders of every description of hand and power freight elevators,” and reported that current demand was “driving that concern to its utmost capacity to keep up with their orders.”[1] The installations referenced in the article also provided evidence of Curwen’s success in transitioning the firm from a regional, New England-based manufacturer to one having a broader national presence. In addition to installations in Massachusetts, Maine and Rhode Island, the article also mentioned installations in Pennsylvania, Michigan and South Carolina. This success apparently led to a plan to increase the size of their factory, as was reported by the Engineering Record in November (no details have survived about the proposed expansion).[2]

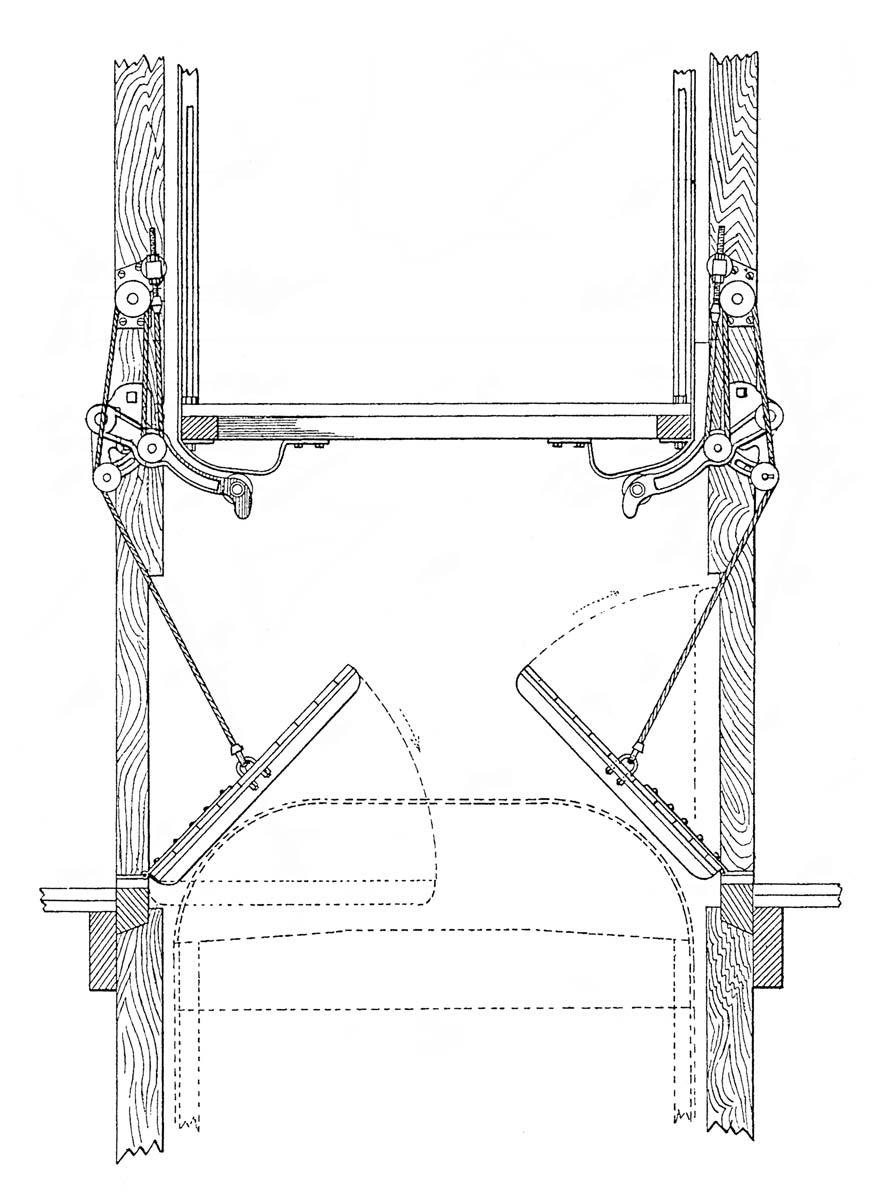

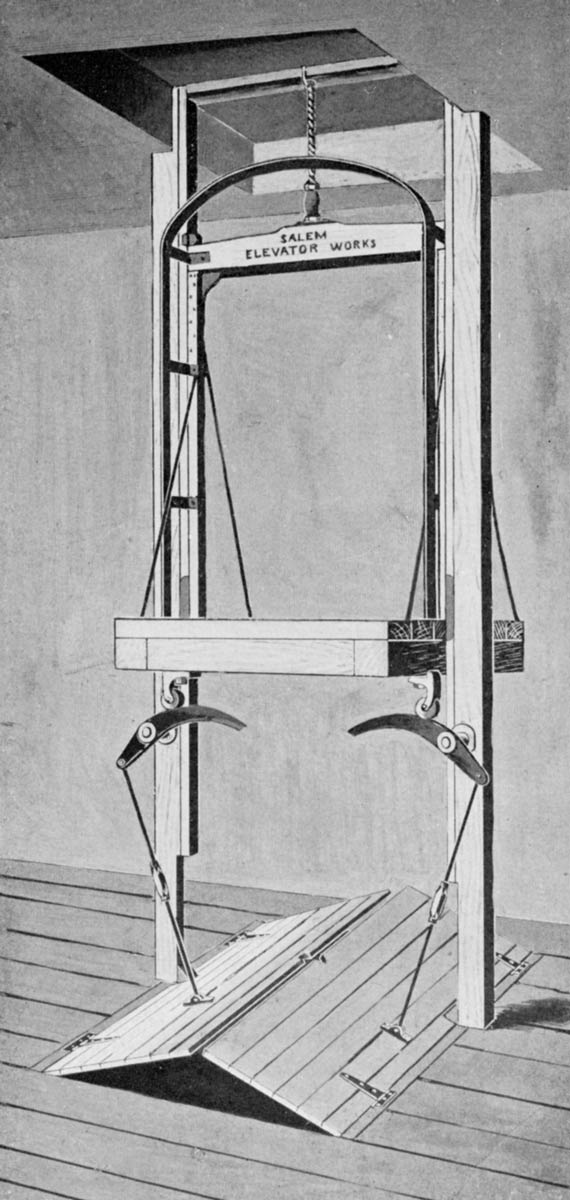

Also, 1891 saw the first elevator patent for an invention that was specifically developed for the company and which was assigned to Curwen: Device for Operating Hatchway-Doors.[3] The inventor was Columbus K. Rogers (b. 1854). Unfortunately, very little is known about Rogers. He apparently pursued a wide range of design and construction projects, which included several elevator patents.[4] However, his 1891 patent is the only one that can be directly linked to the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop.

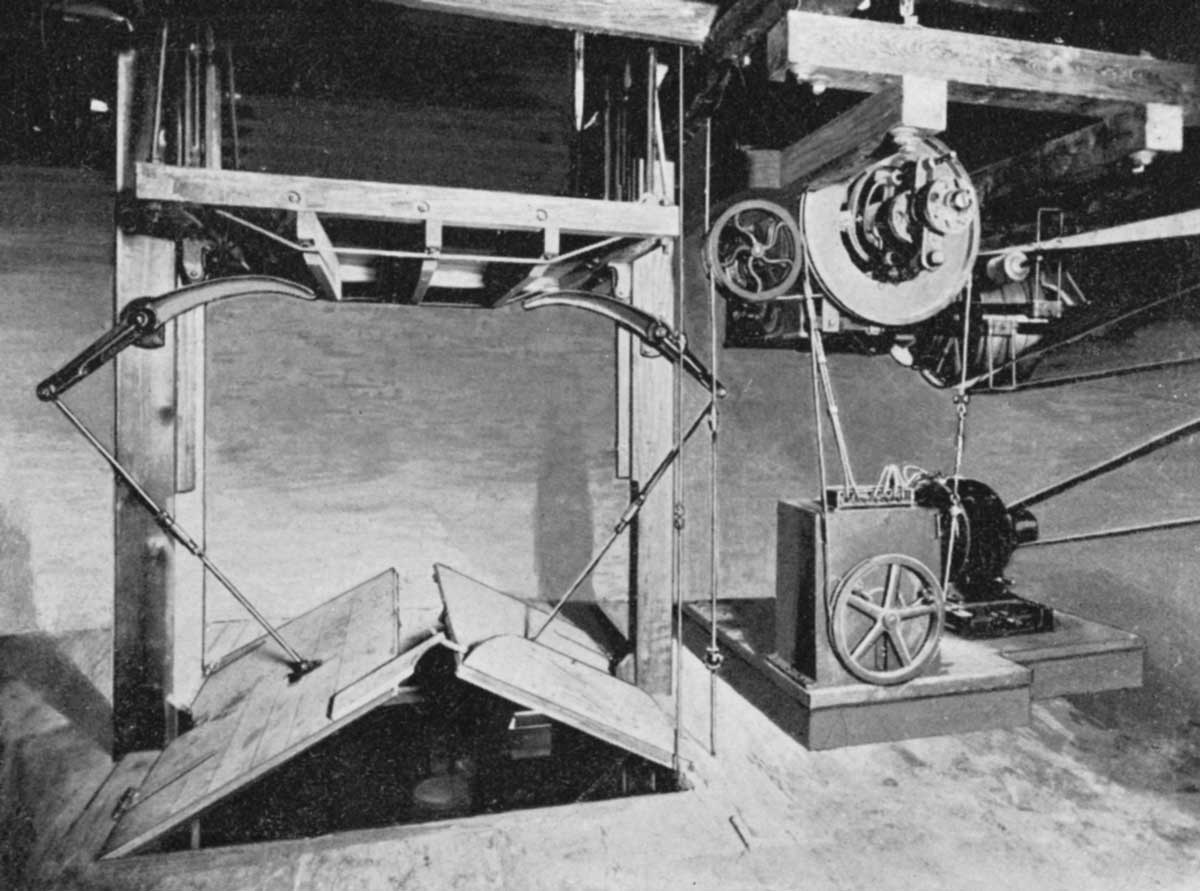

The patent concerned “improvements in self-closing hatches for elevator-wells and mechanism for automatically opening and closing the same by the motion of the car.”[3] Rogers proposed to use ropes to open and close the hatches; however, by the end of the 1890s, the ropes had been replaced by bell-crank levers (Figures 1 and 2). Interestingly, by the early 1890s, the use of bell-crank levers was apparently a well-known means of opening and closing hatches. David B. Clem, in an 1891 patent for an Elevator Hatchway Operating Mechanism, noted that:

“Heretofore this result has been accomplished in various ways — for instance, through the provision of suitably supported bell-crank levers, which project into the pathway of the elevator and at the other end are connected by a rod with the hatchway-doors, so that when the elevator strikes and depresses the first-mentioned ends the later ends will be raised, as will also said doors.”[5]

Rogers’ decision not to use bell-crank levers may have had to do with an attempt to ensure the originality of his design.

In 1892 Curwen placed a press release in the February issue of Architecture and Building:

“The Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, Salem, Mass., report sales of their freight elevators as very satisfactory. The past year has shown a steady increase and the new one opens very promisingly. They build several styles and sizes of belt elevators and are constantly adding improvements.”[6]

Their new products apparently included “large capacity” freight elevators.[6] The following year also witnessed important additions to their product line, which was described as including: “electric, belt and hand power passenger and freight elevators, patent automatic hatches and patent automatic gates.”[7] This was the first reference to passenger elevators and electric elevators. Given the year — 1893 — the production of electric elevators meant that the company was an early adopter of this new technology.

The only known description of their electric elevator dates from 1902. While it recounts the rationale behind their decision to begin building electric elevators, the technical description likely includes developments that occurred between 1893 and 1902:

“The constantly increasing demand for a first-class electric elevator invited our attention some years ago to this line of work, and after giving the matter much thought and spending much time in experimenting, we have been enabled to bring out a machine that meets the rigid requirements of this class of work, and has vindicated the most thorough and practical results. We build this style of machine for either freight and passenger service, of capacities from 500 lb to 10,000 lb, and having a car speed of from 60 to 300 ft/min. Where they have been subjected to thorough tests, they have given perfect satisfaction. The motors have compound cumulative winding, giving great efficiency at the start when the load is first taken, and much care is taken in the proper gradation of the rheostat.”[8]

This was the first reference to passenger elevators and electric elevators. Given the year — 1893 — the production of electric elevators meant that the company was an early adopter of this new technology.

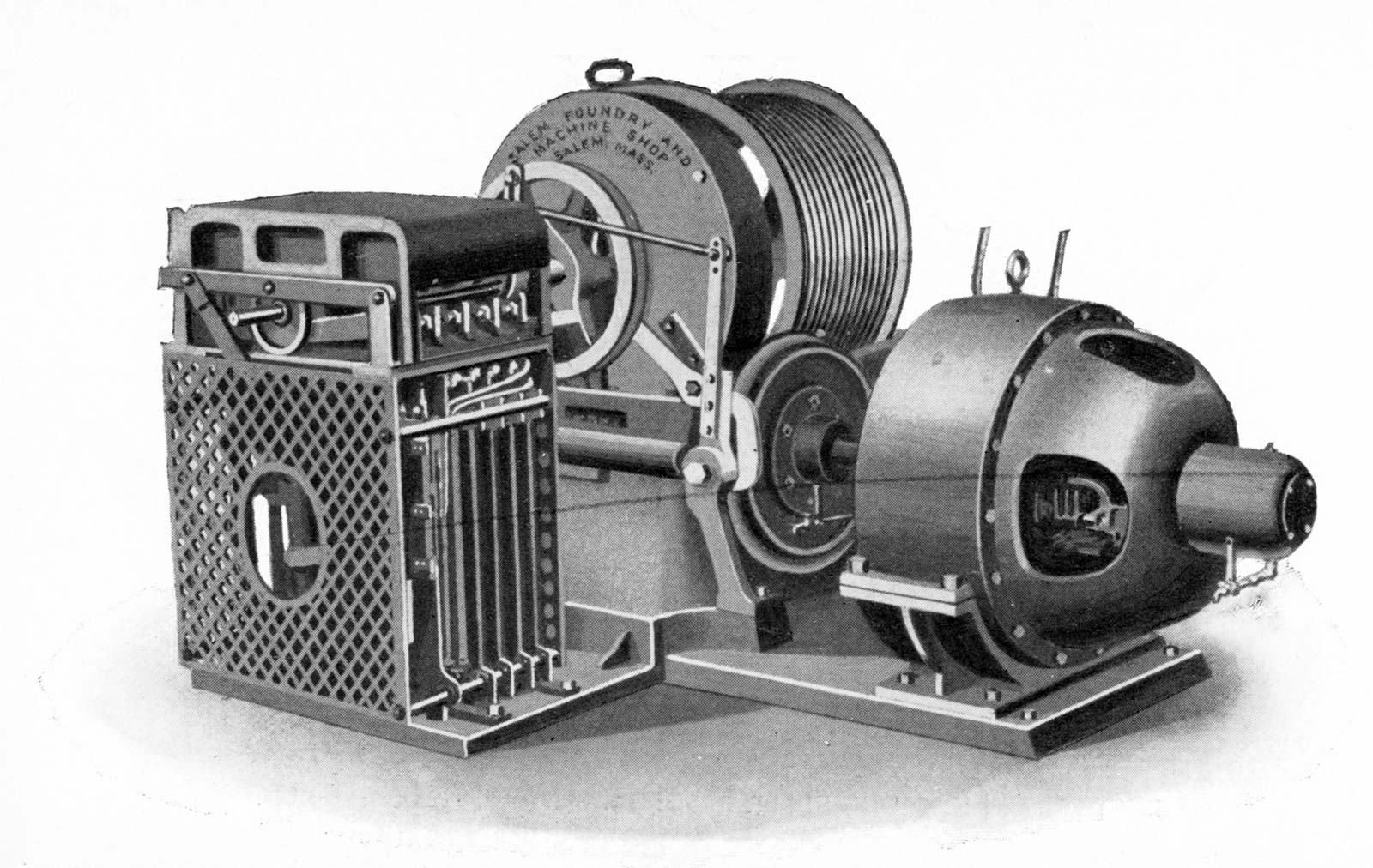

An image of their direct-connected machine, which probably dates from the late 1890s, depicts the motor, controller and winding drum mounted on a single bed-plate, and appears to indicate the use of a worm gear connection between the motor and winding drum (Figure 3).

Unfortunately for Curwen, the launch of his expanded product line coincided with the onset of a significant financial depression that ebbed and flowed throughout the remainder of the 1890s. The impact on the company was reflected in a November 1894 report on its operation:

“The Salem Foundry and Machine Shop, Salem, Mass., reports a decided improvement in its business. It is now running full time with nearly a full complement of help, while during the greater part of the past year it was run 45 hours per week with about one half the regular force.”[9]

The economic slowdown did not, however, dampen Curwen’s determination to continue the expansion of his business. By 1895, the company was advertising themselves as manufacturers of electric, belt and hand power passenger and freight elevators, apartment house lifts, invalid elevators, patent automatic hatch doors and patent automatic safety gates.[10,11] They also described their freight elevators as “especially adapted for mills, factories and mercantile buildings.”[12]

Reflecting the company’s increasing focus on manufacturing elevators, in December 1901 Curwen changed its name to Salem Elevator Works. This change was followed early the next year by the publication of a new catalog, which was immediately sent to the leading trade journals associated with the textile industry:

“The Salem Elevator Works, of which Mr. Charles F. Curwen in the proprietor, at Salem, Mass., has just issued an attractive little catalog, fully illustrated, showing the various kinds of elevators made by them. These include elevators having the belt-driven machine with ceiling and floor pattern; direct-connected electric elevators, hand power elevators, carriage elevators and, in fact, elevators for every kind of service in industrial establishments. Mr. Curwen has been in the business for a great many years, and the elevators made by him have, among other good qualities, the quality that they are perfectly safe. An examination of the little catalog, which will be sent to any address free, will satisfy mill owners that it will be worthwhile for them to correspond with the Salem Elevator Works.[13]

The description of the publication as an “attractive little catalog” was apt: It measured only 6.5 by 3.5 in. in size. It was, however, 24 pages in length and included detailed descriptions of the machines mentioned above, nine illustrations and a list of references.

In the introduction, Curwen highlighted the quality of his machines and the purchasing options available to customers:

“Our machines are constructed of the best materials by skilled mechanics with specially designed tools, and we feel that in offering them to the public, we can guarantee the highest possible efficiency and safety. We furnish these machines delivered and erected complete, ready to belt on to, or delivered f.o.b. Salem, Mass., with full drawings and prints which will enable your mechanic or millwright to erect them, in this latter case saving the expense and time, etc., of sending a man from our manufactory. We would be pleased to send you upon application, estimate blanks for data upon which we can base close figures.”[8]

The offer to send an unassembled elevator f.o.b. (free on board) with “full drawings and prints” advantaged the buyer in that they saved on installation costs. Unfortunately, no records have survived that indicate how many buyers utilized this option instead of employing Curwen’s personnel to do the work.

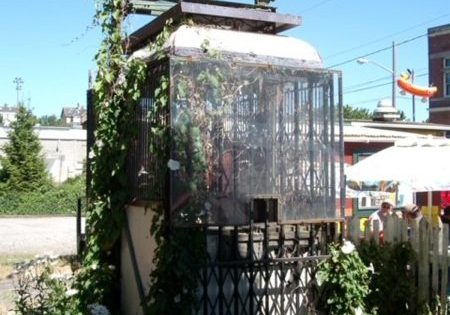

Perhaps the most interesting illustration in the catalog was one labeled a “complete machine” (Figure 4). The image illustrates a belt connected electric machine with the controller and motor placed on a bedplate below the ceiling mounted hoisting engine. The car appears to be descending and thus opening the hatchway doors. However, the image clearly indicates the presence of objects in the shaft below the car that would have obstructed its downward movement. Thus, while this image offers a rare example of an early elevator installation, it also raises intriguing questions.

The catalog concluded with a “partial reference list” of installations. An examination of the list reveals that it included work dating back to 1889 (and perhaps earlier). Thus, it encompasses the majority of the company’s elevator production. It includes references to the installation of 538 elevators in 19 states located throughout the eastern and southern United States, with many of the installations occurring in textile mills or textile-related companies. Curwen’s success in marketing to this industry was dramatically illustrated by the number of elevators “used in textile mills,” that were regularly referenced in the company’s advertisements, beginning in 1898:

- 1898 “more than 200”[14]

- 1904 “over 450”[15]

- 1907 “over 1000”[16]

- 1909 “over 1500”[17]

These numbers offer clear evidence of Curwen’s entrepreneurial skills. During his 30-year tenure, he transformed the Salem Foundry and Machine Shop from a local generalist manufacturer into Salem Elevator Works, which specialized in building freight elevators that powered a significant portion of an entire industry. After Curwen died in December 1909, the firm he left behind continued on well into the first half of the 20th century and continued to build on his legacy.

References

[1] “Special Mention,” Architecture and Building (July 4, 1891).

[2] Untitled, Engineering Record (November 28, 1891).

[3] Columbus K. Rogers, Device for Operating Hatchway-Doors, U.S. Patent No. 456,063 (July 14, 1891) (Patent assigned to Charles F. Curwen).

[4] Automatic Hatchway-Guard for Elevators, U.S. Patent No. 313,450 (March 3, 1885); Automatic Elevator-Brake, U.S. Patent No. 313,451 (March 3, 1885); and Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 349,177 (September 14, 1886) (Patent assigned to Zina Goodell and Abner C. Goodell, Jr.).

[5] David B. Clem, Elevator Hatchway Operating Mechanism, U.S. Patent No. 449,361 (March 31, 1891).

[6] “Special Mention,” Architecture and Building (February 20, 1892).

[7] Dockham’s American Report and Directory of the Textile Manufacture and Dry Goods Trade 1893-94, Boston: C.A. Dockham & Co. (1893).

[8] Salem Elevator Works, Electric, Belt, and Hand Power Elevators (1902).

[9] Untitled, American Manufacturer (November 23, 1894).

[10] The Naumkeag Directory for Salem, Beverly, Danvers, Marblehead, Peabody, Essex and Manchester, 18965-96, Salem: Salem Observer Office (1895).

[11] Boston City Directory, Boston: Sampson Murdock and Company (1895).

[12] Advertisement, Architectural Record (December 1895).

[13] “Among the Mills,” The Textile Record (May 1902).

[14] William Whittam Jr., Cotton Spinning, Second Edition, Providence: C.A.M. Praray & Co. (1898).

[15] Transactions of the New England Cotton Manufacturers Association, No.77 (1904).

[16] Transactions of the New England Cotton Manufacturers Association, No.83 (1907).

[17] Transactions of the New England Cotton Manufacturers Association, No.87 (1909).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.