The Sherrill-Roper Hot-Air Engine

May 1, 2022

In this History article, readers learn about the change from steam to a new way of generating heat.

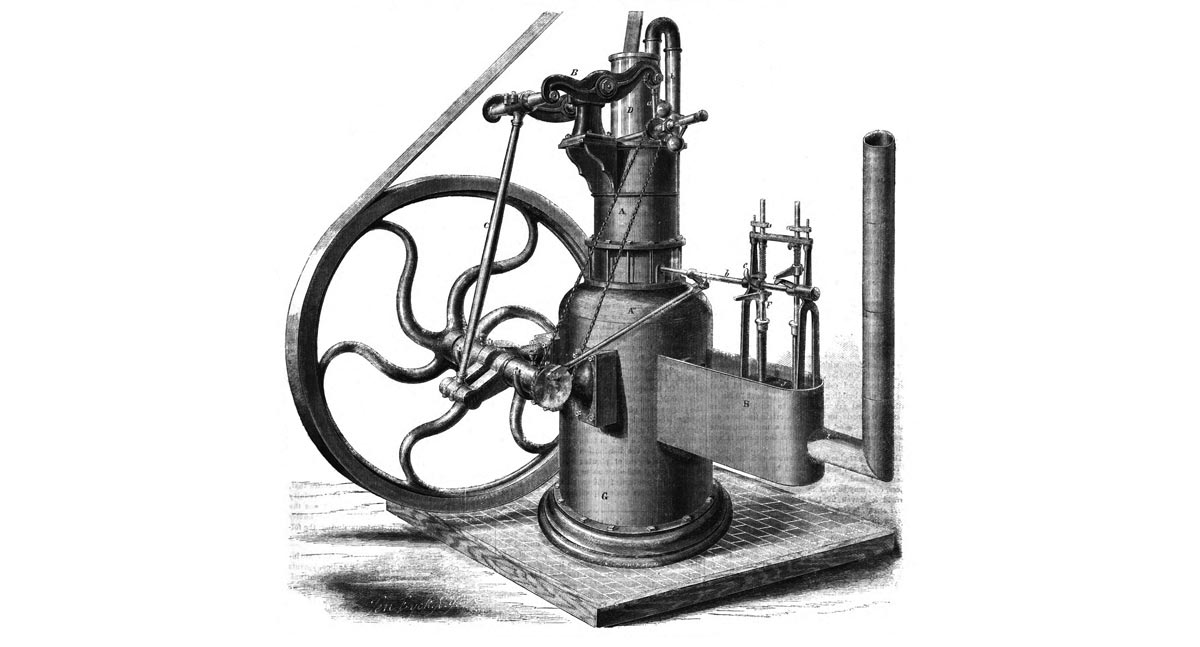

In 1862, Boston inventor Sylvester H. Roper (1823-1896) received the first of three patents for an engine powered by hot air. Roper, who later became well-known as a pioneer in the development of steam-powered automobiles and motorcycles, essentially removed the steam from the engine model and replaced it with heated air (Figure 1). This engine type, also known as a “caloric engine,” had been initially developed in the early 1800s, and Roper’s design was viewed a significant improvement on past models:

“The engine is exceedingly simple. It may be regarded as a steam engine worked by air, with the furnace inside of the boiler … The air enters the heating chamber through two pipes, one above the grate and one below; the larger portion of the air entering above the grate. This arrangement prevents a blast through the fire that would carry ashes and bits of unburned coal into the cylinder.”[1]

The engine was described as more energy efficient than steam-powered systems: “A sufficient quantity of coal is introduced in the morning to last till noon, so the engine does not require to be stopped for feed any more often than men must stop for the same purpose.”[1] A final critical advantage of this system was also cited in early accounts of its design and operation: “And lastly, though by no means the least consideration in these tight times, is the fact that the rates of insurance are not increased by using them in any building.”[2] This latter advantage was often highlighted in articles that described the engine:

“It is absolutely free from all danger of explosion, and safer against fires than a common stove. Being perfectly safe, it is exempt from the extra rates of insurance charged by companies on engines of this class … In comparing this machine with the steam-engine, its favorable features are readily seen. It consumes less fuel, while the danger of boiler explosions with their attendant loss of life and property is totally obviated.”[3]

By 1870, approximately 1,000 Roper hot-air engines were in use throughout the Eastern U.S.

The engine met a critical need in American industry. Its relatively small size, simple design and ease of operation, which did not require the business owner to hire an engineer or trained mechanic, meant that many settings that had previously relied on hand or horsepower could employ an engine to power their machinery. In many ways, its use foreshadowed the application of electric motors in the 1880s and 1890s. By 1870, its versatility was well established and it was described as appropriate “for all purposes where small motive power is required, to wit: driving printing presses, lathes, pumping, sawing, elevating, crushing sugar, carrying shoe-manufacturing machinery, donkey pumps, railroad depot uses, domestic and farm purposes; in short, all sorts of mechanical works, too numerous to mention.”[4]

Crosby, Butterfield & Haven in NYC were the original manufacturers, and in 1869 Roper established the Roper Caloric Engine Company (also located in NYC) to build and market his design.

In the early 1870s, two individuals who joined the new company both ensured its success and, by the late 1870s, expanded its use to include elevators. In 1872, New York businessman Henry A. Sherrill began serving as company treasurer. While he successfully watched over the firm’s financial matters for more than 15 years, his primary contribution to its success was his decision to hire his nephew, Henry W. Sherrill (1853-1900). The younger Sherrill, although born in Wisconsin, had been educated in Easthampton, Massachusetts, where he attended the Williston Seminary (now the Williston Northampton School), which offered its students a choice of studying classics or science. Given his inventive nature, he likely studied science. In 1878, he filed two patent applications, one that concerned an improved hot-air engine design, and one that concerned the application of the engine to elevators.[5, 6] The hot-air engine patent was assigned to the Sherrill Roper Air Engine Company. The change in the company’s name illustrated the increased importance of the Sherrill family in the business’ operation.

The January 1879 issue of the “American Machinist” included an illustrated article that discussed the application of the Sherrill-Roper engine to elevator systems. The author introduced his subject by describing the general state of the vertical-transportation (VT) industry:

“The almost universal use of elevators in warehouses, manufactories and public buildings has given rise to great competition in designing and building them. While much skill has been directed to the carriage itself, the economical and reliable working of the whole apparatus is mainly dependent upon the power which drives it. In most cases, the power is steam, requiring a boiler, an engine and a skilled engineer. It is true that the last is not always employed, but economy as well as safety demands that he should be. It has been a question whether some motive power, cheaper, safer and as efficient as steam could not be employed for elevators, especially where but little power is required.”[7]

The answer to the question posed by the author regarding a suitable replacement for the steam engine was, of course, the Sherill-Roper hot-air engine.

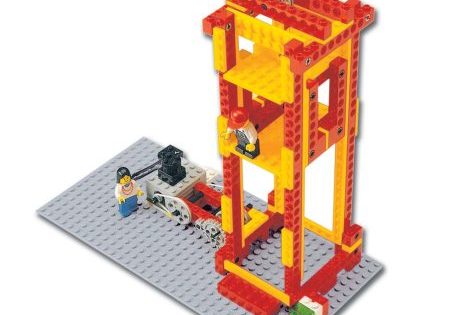

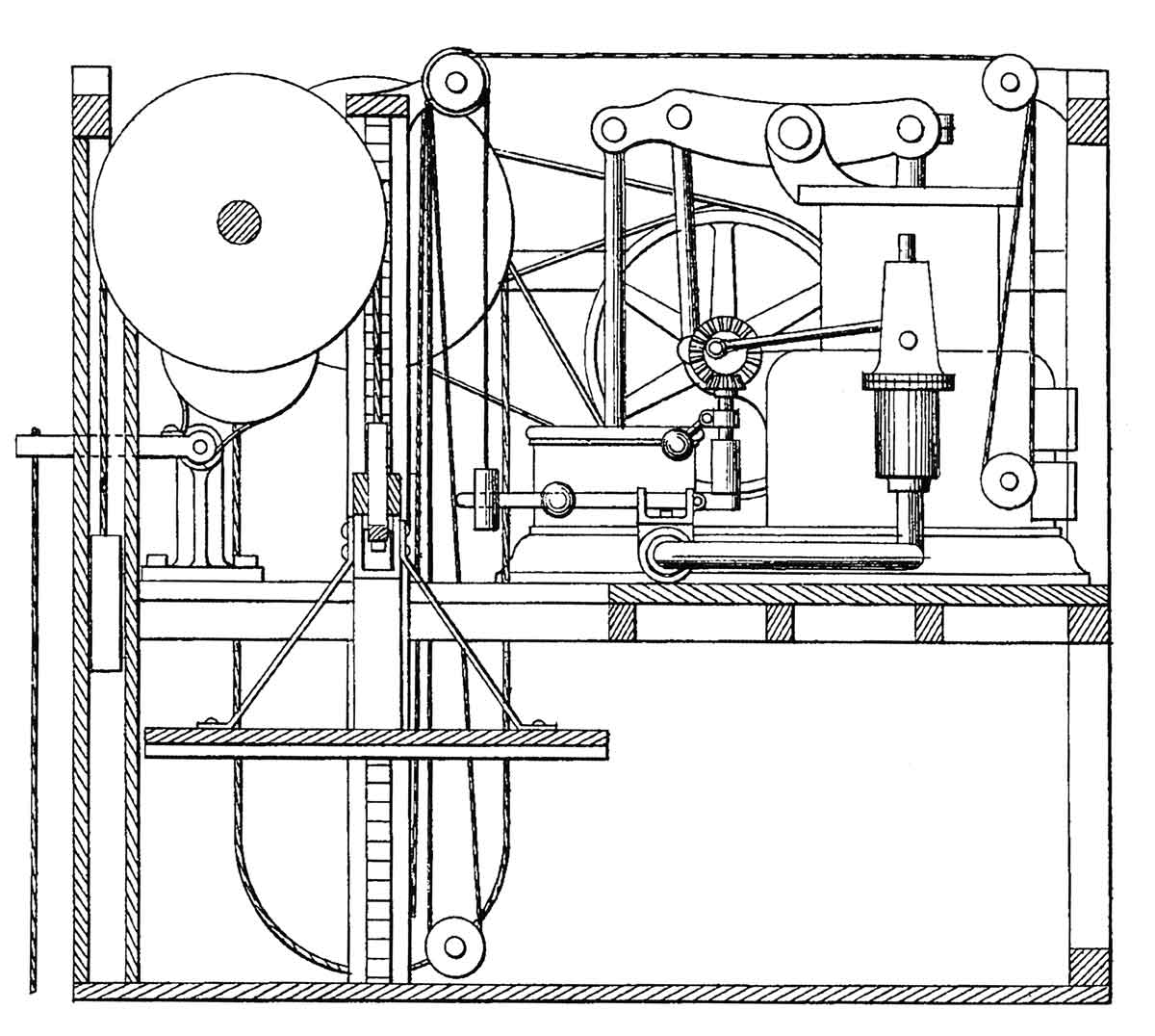

The article’s illustrations included an image that depicted the hot-air engine connected via a belt to a typical overhead mounted geared winding drum machine whose action was controlled by a shipper rope (Figure 2). The engine was characterized as “driving a safety elevator” that was “provided with safety guides and pawls.”[7] This description, and the platform’s overall design, clearly resembled systems manufactured by the Otis Brothers. This similarity was made possible by the fact that Elisha Otis’ original patent had expired and his ratchet and pawl safety device was now available for use by other VT industry members. The location of the shipper rope in the engraving is also worth noting, as it did not pass through the platform but was placed adjacent to its edge. Thus, in order to grasp the rope, the operator had to extend his hand outside the platform area, which constituted a significant (but common) operational hazard. Additionally, the elevator platform traversed an open hoistway, which did not employ safety hatches or gates at the floor openings.

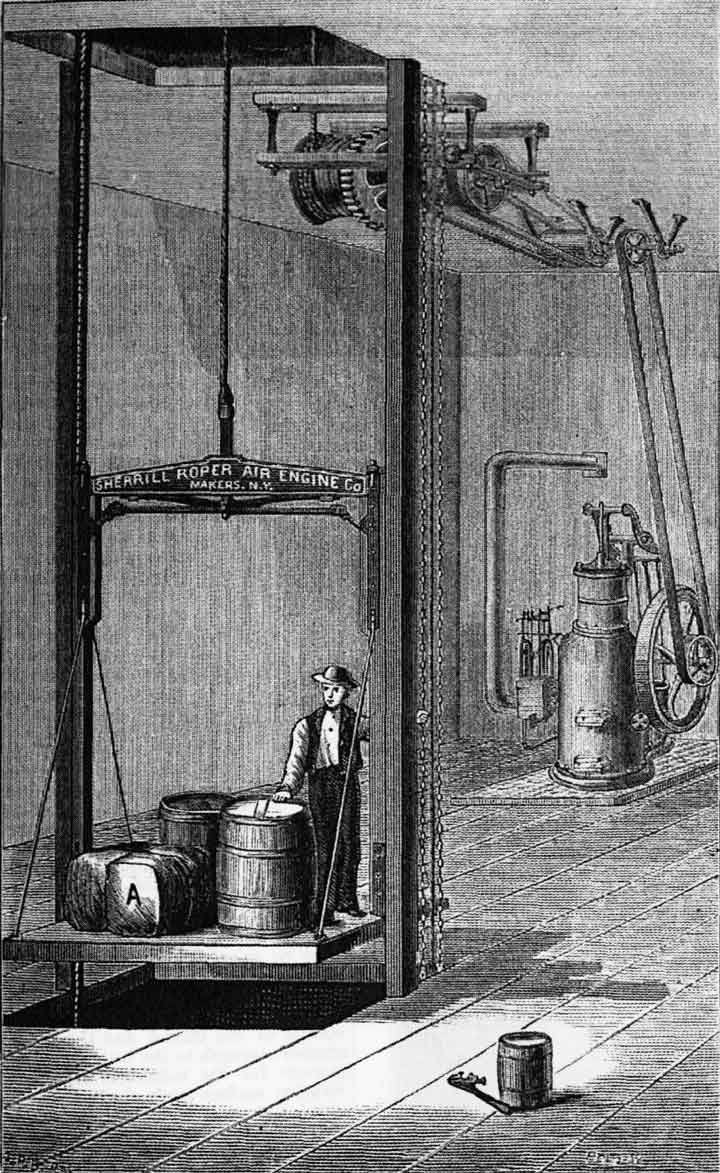

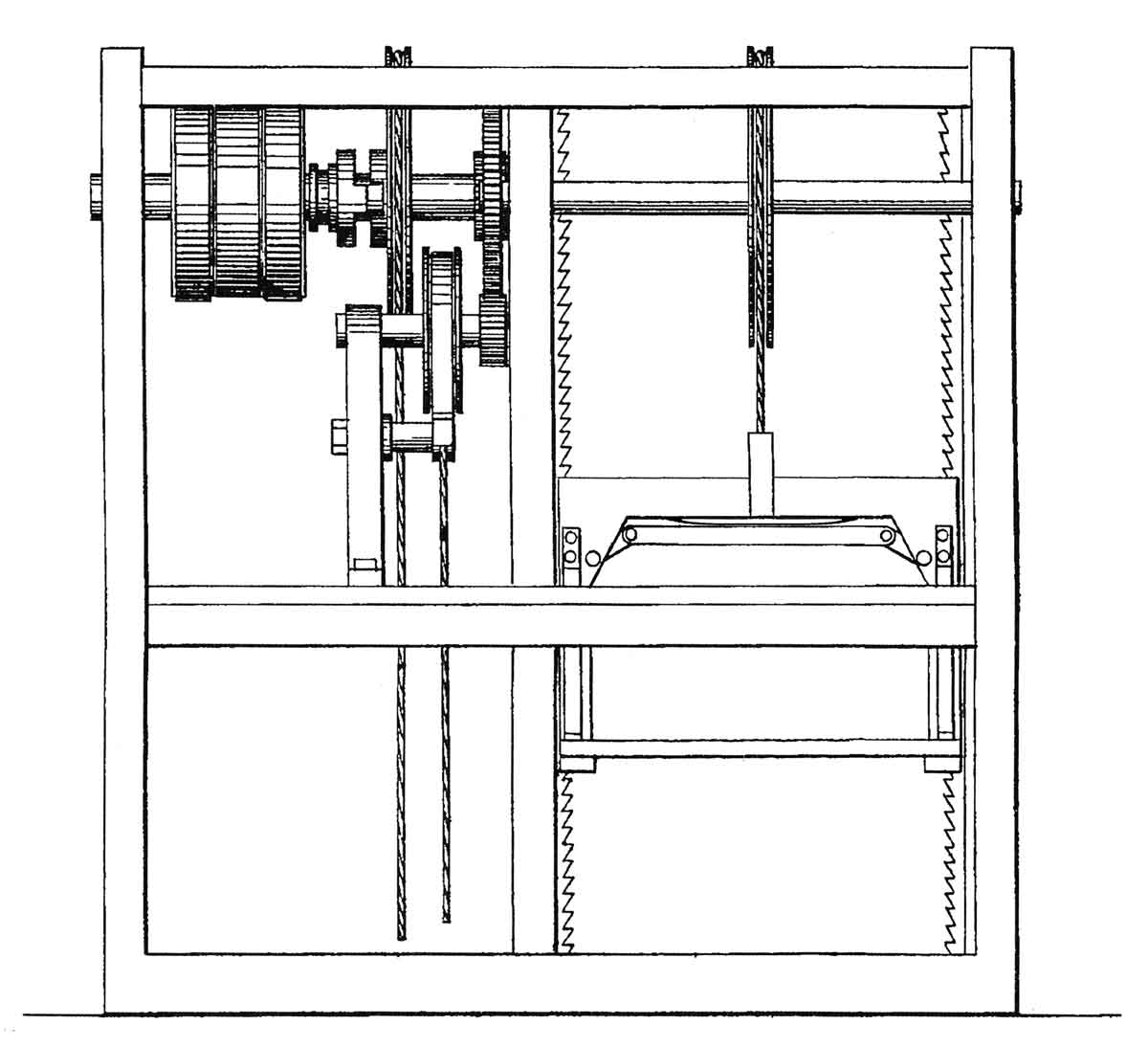

Sherrill’s elevator patent, titled Improvement in Combined Elevator and Operating-Engine, also dated from early 1879. The design represented one of the first times the hoisting engine was located at the top of the shaft (Figures 3 & 4). The engine employed a belted connection with the gearing that controlled the platform’s movement. The presence of two belts, one open and one crossed, allowed the engine to run in a single direction, with the belt shipper and pulley system attached to the platform gearing determining the direction of operation (up or down). The design also featured a secondary hoisting rope that permitted hand-powered operation. A hand-operated clutch was used to switch from the engine to hand power (if needed). Interestingly, the design did not employ a winding drum. The single rope linking the car and counterweight passed over a large sheave, which resulted in the system functioning somewhat like a traction elevator. There is, however, no evidence that any elevators were built following this intriguing design.

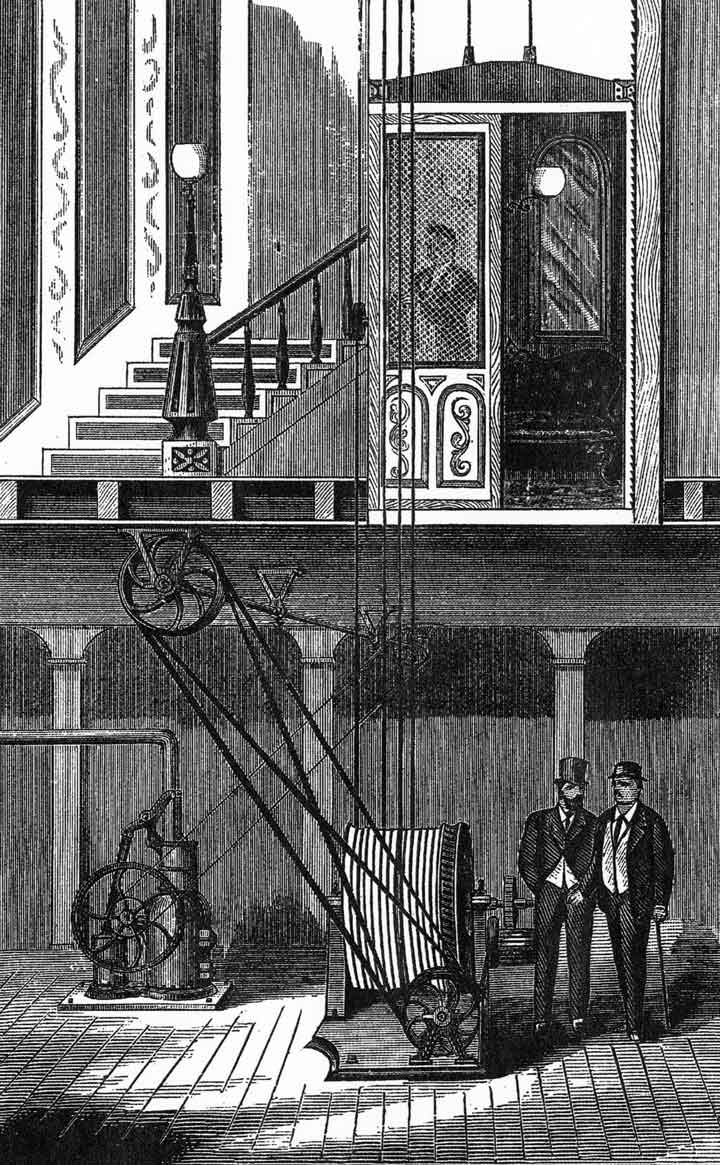

The favorable press the company was receiving, and Sherrill’s patents, may have contributed to their decision in 1879 to focus almost entirely on elevator manufacturing, a change explicitly expressed in their contemporary listing in the New York City Directory, where they described themselves as “manufacturers of improved air engines, elevators and hoisting machinery.”[8] The August 1882 issue of the Manufacturer and Builder featured an article that included the first illustration of a Sherill-Roper engine driving a passenger elevator (Figure 5). The image followed the format found in similar images produced for rival manufacturers: a basement installation featuring a large winding drum machine with well-dressed men admiring the machinery, and an elegant elevator car stopped on the first-floor landing. While the article reported that Sherrill-Roper had “provided numerous appliances for insuring safety in the operation of their passenger and freight elevators and other hoisting machinery,” no details of their safety devices were provided.[9]

One of the last articles on the company appeared in 1883, which described a variety of overhead mounted geared machines “suitable to be driven by steam, air, or by hand.”[10] However, these machines were described as manufactured by a new company — the Sherrill Elevator Works — which had been, apparently, established as a subsidiary of the Sherrill-Roper Air Engine Company. Intriguingly, this reference marked not only the first, but also the last mention of this company. Additionally, by 1885 Sherrill-Roper appears to have closed and Henry W. Sherrill left the VT industry to pursue a career in real estate. While the article’s author thus unknowingly offered readers a last glimpse of this company, he also provided readers with a detailed assessment of the importance of this emerging technology:

“The elevator, in some one of its numerous forms, has so fully demonstrated its usefulness and serviceability as a laborsaving machine, that it has become indispensable everywhere, not only for the raising and lowering of goods, but for its more recent but none the less indispensable service as a conveyer of passengers. For the latter service, indeed, its introduction has not only enormously increased within the past few years, but it may truly be said to have called into existence a new type of architecture — namely, the extremely high, towering buildings that form so distinctive a feature of the modern portions of our cities. It is safe to affirm, that without the elevator, to spare suffering humanity the fearful muscular strain involved in reaching their upper stories with the means that nature has provided, the solid blocks of six, seven and eight storied structures that grace the business centers of most of our American cities would have no existence.”[10]

Thus it is, perhaps, not unreasonable to identify the Sherrill-Roper hot-air engine, with its versatility, safety and ease of operation, as having played an important role in helping to establish the elevator as an “indispensable” feature of modern life.

References

[1] “Improved Air Engine,” Scientific American (December 3, 1864).

[2] “Roper’s Caloric Beam Engine,” Scientific American (February 14, 1863).

[3] “The Roper Caloric Engine,” Manufacturer and Builder (August 1871).

[4] Advertisement for the Roper Caloric Engine found in: The Men who Advertise; An Account of Successful Advertisers, New York: Nelson Chesman (1870).

[5] Henry W. Sherrill, Improvement in Hot-Air Engines, U.S. Patent No. 212,275 (April 1, 1879).

[6] Henry W. Sherrill, Improvement in Combined Elevator and Operating-Engine, U.S. Patent No. 213,783 (February 11, 1879).

[7] “Air Hoisting Power,” American Machinist (January 1879).

[8] Trow’s New York City Directory for the Year Ending May 1, 1880, New York: Trow City Directory Company (1879).

[9] “The Air Engine as Applied to Elevators,” Manufacturer and Builder (August 1882).

[10] “Improved Hoisting Machinery,” Manufacturer and Builder (September 1883).

Also Read: Rope-Drive Elevators

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.