The Social Value Act

May 29, 2024

How it came to be and its role in the future

In 2012, a historic moment arose and changed how public service contracts would be awarded in the U.K. moving forward, whether it be elevator contracts, facilities management contracts or any other contract to fall under the public scope. The act was not prescriptive; it was to encourage a cultural change, and it was left up to procurement officers to decide if they would or would not include it within their tendering process. If it were included, then all tenderers would have to adhere to the new rules, otherwise their tenders would be deemed as non-compliant, and they would be struck out from the tendering process.

So, what is the Public Services Act or the name it is most commonly known by: the Social Value Act (SVA)?

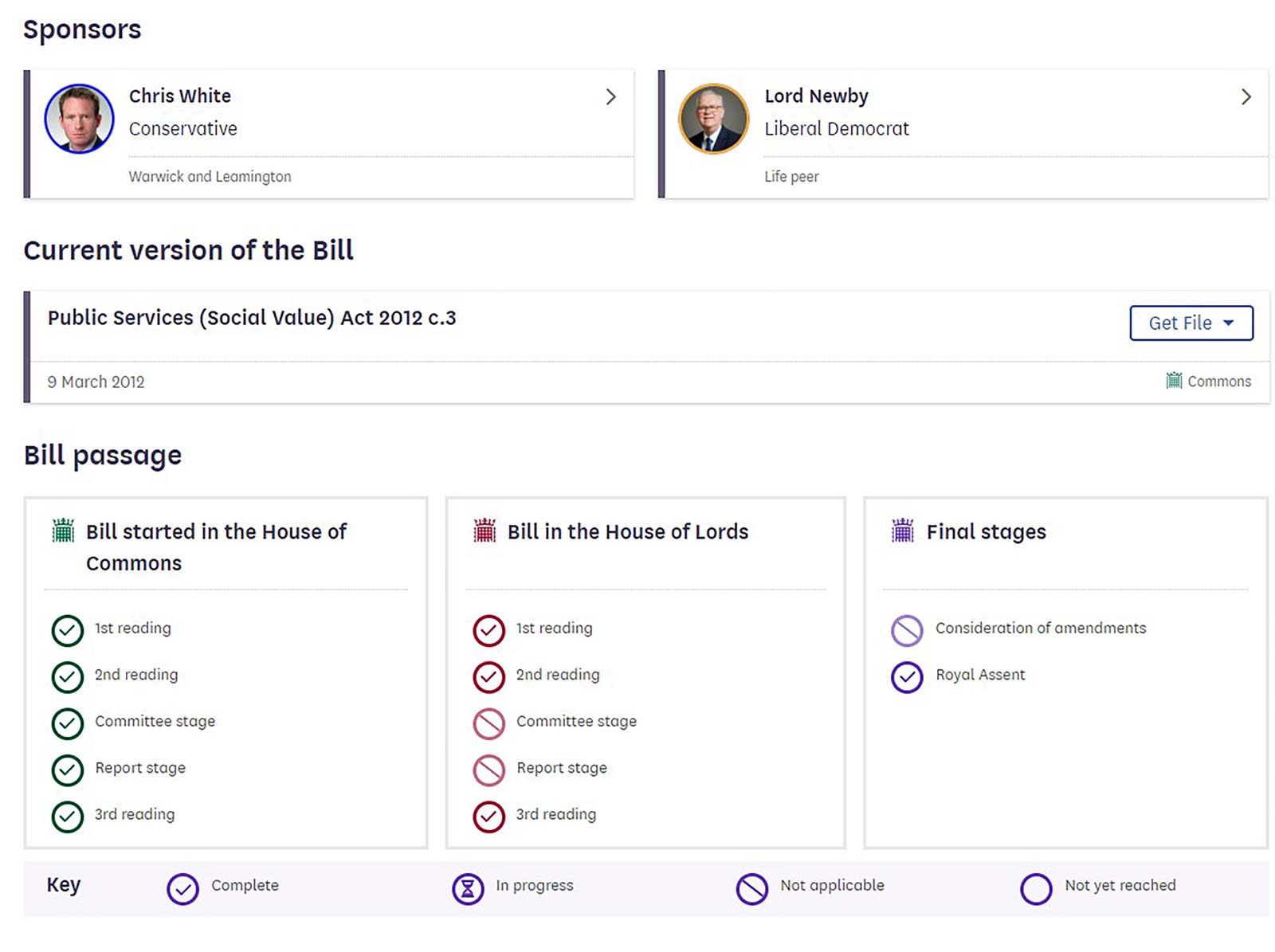

In June 2010, then member of Parliament (MP) for Warwick and Royal Leamington Spa, the right honourable Chris White, brought forward the bill in the House of Commons under the original name of the Public Services Bill. It was brought in to be voted on via a private members bill (PMB), which generally isn’t given as much attention as a normal bill, fails to gather momentum and is without any chance of success. To put this into perspective, since World War II, less than 10 PMBs have been successful in being written into legislation.

This one was different, though. It was pushed forward and campaigned for by Social Enterprise UK (SEUK), a scheme that aims to help all with the following remit:

“Social enterprises are businesses. Like any other business, they seek to make a profit and succeed commercially. But how they operate, who they employ, how they use their profits and where they work is transforming lives and communities across the U.K. and around the world. Social enterprises work in every sector of the U.K. economy, creating and trading consumer products and services, providing local community resources, running creative agencies, arts organisations, recycling projects, cafes and restaurants, cleaning services and waste management companies. Social enterprises also provide high quality public services, and as many as a third of community healthcare providers are social enterprises.”

The bill aimed to encourage the wider benefit of social value for the community rather than just financial value. White stated:

“We were very conscious of the economic landscape. Legislation that was deemed too burdensome for business would simply not pass. It was designed to be permissive and flexible and not restrict the individual public bodies. As a great American president once said, ‘I’m an idealist without illusions’ (John F Kennedy).”

Due to it being non-controversial, the bill gathered pace with cross party support, and eventually, in 2012, The Public Services Act was given Royal Assent, meaning it was finally able to be written into law.

In 2014, Lord Young reviewed the scheme and completed a report that can be seen online. Although excited about its potential, he was critical about how it was not being widely used and felt more work was needed in three particular areas.

The areas of awareness and not many public bodies taking up the scheme was slowing its progress and potential — the second being the varying knowledge and understanding of the act and the way to implement it, and the third being how to actually measure the social value of it.

Figure 1 shows the whole process that the bill had to go through before being written into legalisation, first through the House of Commons and then through the House of Lords.

After Lord Young’s review, 2016 saw the social value task force set up to develop, promote and steer the act in the right direction so it didn’t become one of those acts that is forgotten about and subsequently falls flat on its face, residing only in a few memories and the archives of the parliamentary library.

By 2019, the Act’s biggest milestone was the creation of The Themes, Outcomes and Measures framework (Tom’s Framework). The framework provides a toolkit to help organisations, both public and private, navigate their way through the process in an easy and transparent manner that allows the smooth measuring, distribution and allocation of tenders.

So, 10 years on from the review and 12 years on from the act being implemented into legislation, what has changed? What has been learnt, and how does it now affect vertical-transportation industry contracts in 2024?

In the past 12 years, results have estimated that £56 billion have been missed out on by the act not being used to its full potential. On the plus side, it also estimated that £100 billion have been influenced coming directly from Social Value by 2025.

The act has certainly picked up pace and is now even championed by central government, which advises all public bodies to include it in their tenders. It has been a long, drawn-out process and is by no means perfect even in 2024. There is still much to do, and SEUK’s 2032 Roadmap and the SV taskforce go into fine detail on how it will be achieved.

It will always be a working project, but what started in a near-empty House of Commons on a Friday morning as a PMB, when nearly all members of parliament were in their constituencies, certainly shows the hard work, determination and perseverance of its pioneers, that of White, now professor at Kings College London; Hazell Blears, MP, now chair of the Board at Social Investment Business; Andrew O’Brien, director of Social affairs from SEUK; and Mark Cook, who also helped draft the bill.

And in a time when the U.K. has seen huge government under investment across all of its infrastructure, social value will be expected to plug some gaps that central government cannot or will not, even more so if the government goes ahead with its post-election cuts, which will mean vital public services not protected.

Example of Lives Affected

Through many meetings, Shaw Trust and Somerset County Council created a 10-year collaboration that would change services for children and young people within the county on a never-before-seen scale.

The partnership is an overhaul of the system, and in 2020 in England, more than 80,000 children were taken into care — a figure up by 16,000 from 2010. The trust will deliver £1 million of social value over the course of the project.

In the pipeline are new children’s homes, foster homes, therapeutic education and experiences and support for disadvantaged children who have suffered adverse trauma and deteriorated mental health. The new services will also create job opportunities in the care sector with much training development on the cards.

The Extra Mile

As the above from Somerset County Council and Shaw Trust proves, when the act is understood and implemented by the commissioning officer correctly, its impact can be hugely significant.

There are many success stories that have evolved, not just in health but also in developing local infrastructure. In Salford, the meticulous and robust ITTs have managed to upgrade the bus routes around the city, as well as employ numerous apprentices.

The act is evolving and intertwining with others and going from strength to strength with more and more bodies getting onboard. With massive government underspending, it creates a pathway for direct investment into its services.

At the moment, the scheme is decided upon by the tender officer or the local body; however, the act is closely linked with the Corporate Social Responsibility Act, which used to be voluntary but is now mandatory. Could this be on the cards for this act?

What Is Next?

Just as everyone is getting used to the SVA comes a twist, as the government casts the net out a little further.

In October 2023, The Procurement Act was given Royal Assent, and it will be written into law in England, Northern Ireland and Wales (Scotland will keep its own procurement process) in what is expected to be October 2024.

What is coming next is a greater symbiosis between politics, law and business. Procurement will now focus more on MAT (most advantageous tender) instead of MEAT (most economically advantageous tender), as the government changes its strategies and policies to level a few playing fields due to the collapses of mega companies Carillion and Interserve, the latter of which was handed a £660 million public services contract in the build up to it going into administration. More recently, lessons were learnt from the Department of Health and Social Care when they wasted 75% of £12 billion on inadequate personal protective equipment that could not be used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Of course, value for money will always be top of the shopping list, but more power will now be given to also look at SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprise) due to the relaxation of Section 17 of the Local Governments Act 1988, which now means a duty has been placed on the authorities to decide whether certain barriers that had previously held the smaller companies back from bidding for larger contracts because they did not meet the correct threshold can be removed. This is a bold move that is sure to shake the apple tree of a few corporations.

These changes mean due diligence will be vital, and companies will have to be transparent when it comes to their supply chain and procedures, as the commissioning officers will need to make sure the supply chain is beyond reproach and sustainable. Companies like Reprisk.com will be used to check claims and a company’s reputation. Any company found to be “Social Value Washing” or “Green Washing” could suffer severe consequences and huge fines.

The Government will be running training schemes for all its commissioning officers to provide them with skills. They will be contacting all trade associations and business groups to liaise and give guidance and support so these groups can fully understand their roles within the new changes.

The new bill could be very good for those willing to embrace it, especially when there is £300 billion worth of business within all its areas on which to bid.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.