The challenges of predicting the future

Famous quotations from William Shakespeare include a well-known line from Act II of “The Tempest,” in which Antonio tells his brother Sebastian: “What’s past is prologue.” A simplified explanation of this statement is that the past has a connection to the future. In the case of “The Tempest,” it is used to imply that a person’s past actions determine their future actions. An expanded interpretation is that an awareness of the past is necessary to understand the origins of present events and, additionally, that this awareness may also function as a guide to anticipating (or predicting) the future. However, sometimes the past is just the past, having no connection to future events. Likewise, sometimes the future has no discernable connection to the past. Lastly, and perhaps most intriguingly, sometimes the future arrives without warning — and we miss the opportunity it represents.

Kenneth M. White was born on October 14, 1903, in Cataract, Indiana (an unincorporated town located approximately halfway between Indianapolis and Terra Haute). He attended Purdue University, graduating in 1927 with a B.S. in electrical engineering. Nothing is known about his childhood in rural Indiana or his university career. Another unknown is why, immediately after graduation, he accepted a position with the Westinghouse Electric Elevator Company in Chicago. It may have been that White simply thought that a position at a national company was a reasonable starting point for his career. In other words, what the company made was not the determining factor in his pursuit of this position. Of course, another possibility is that White actively sought out a career with an elevator manufacturer. Whatever his motivation, what is known from the historical record is that he had found a career that he thoroughly enjoyed and in which he excelled.

White’s career with Westinghouse may be tracked, in part, by the patent record. He filed his first patent application in 1930 (his third year with the company). The patent, for an elevator motor control system, was the first of nine patents he received while with Westinghouse.[1] The dates of his patent applications, ranging from October 1930 to July 1936, reveal the intensity of his design efforts and his quick grasp of elevator engineering. White began this work living first in Chicago (1927-1931), followed by Mooresville, Indiana (a suburb of Indianapolis: 1931-1933), and ending in Tenafly, New Jersey (located across the Hudson River from Yonkers, New York: 1934-1936). White appears to have left Westinghouse in 1936. He took advantage of his proximity to NYC to explore a different type of elevator-related employment. Over the next three years, he worked for Banker’s Trust and Rockefeller Center, overseeing their respective elevator operations.[2] The latter had, at the time, one of the largest elevator plants in the world.

White’s reasons for leaving Westinghouse are unknown. His reason for leaving NYC in 1939 is, perhaps, less mysterious. He left the “big city” and moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where he joined the American Elevator and Machine Company as their general manager and chief engineer. He may have been recruited by the company’s president, Roland I. Phillips (1879-1954). Phillips had served as president of Westinghouse in Chicago from 1925 to 1936.[3] Thus, Phillips very likely knew White from his time with Westinghouse and, learning he had left the company, succeeded in luring him to Louisville.

White’s return to elevator manufacturing was marked by a return to design and invention, which resulted in two patent applications filed in 1941. The patents concerned a variable voltage elevator control and an elevator signaling system.[4] The latter reflected White’s growing interest in developing systems that would permit more efficient elevator operation:

“This invention relates to elevator signaling systems and relates more particularly to systems for indicating that a passenger who has signaled for an elevator car to stop at a floor of a building has been waiting for more than a predetermined length of time. In the interests of operating efficiency and, particularly during rush hours, it often happens that passengers waiting at intermediate floors of a building are forced to wait for extended periods of time for a car. Often the operator of the car cannot stop for the reason that the car is already filled, and no good purpose would be served by stopping and thereby delaying the transportation of the passengers already in the car. In as much as extended periods of waiting cause annoyance to the prospective passengers and complaints regarding the elevator service, it is desirable to have some means for indicating to the elevator operator and/or the starter the fact that some of the prospective passengers have been waiting for too long a period of time.”[5]

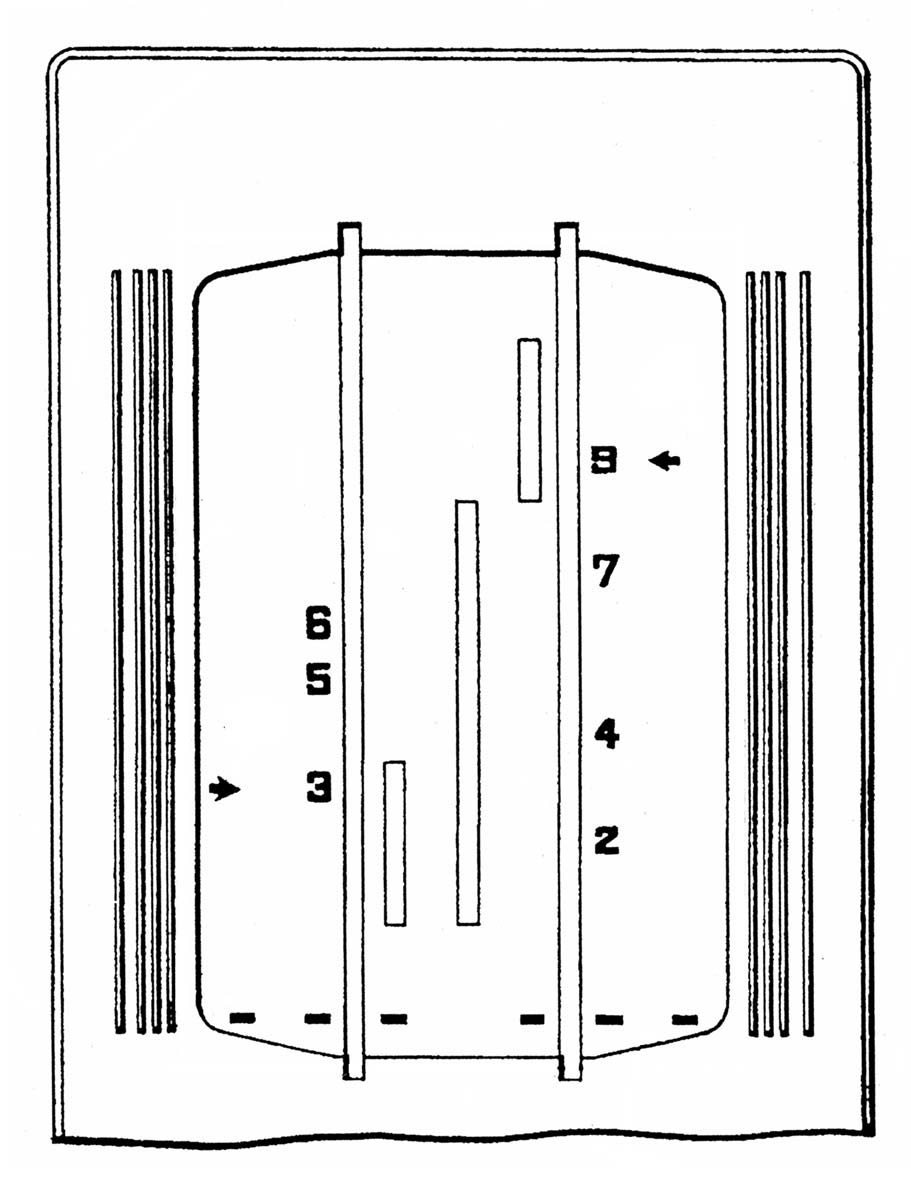

White designed a “simple and accurate timing mechanism” that was attached to the signal panel in the car.[5] The panel featured two parallel columns of floor numbers that illuminated when a waiting passenger pushed a hall call button. The column on the left registered “down” calls and the column on the right registered “up” calls. If a call went unanswered for a preset length of time, an arrow would appear adjacent to the floor number, which indicated to the operator that they must stop at that floor on the next run (Figure 1).

The application for White’s signal system was filed on December 5, 1941. Two days later, the course of history was changed with the bombing of Pearl Harbor. During World War II, White served as chief engineer of the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant in La Porte, Indiana.[2] In 1945, White returned to American as its vice-president; however, his time with the company was short-lived. In the summer of 1947, Phillips stepped down as president, and in August, the company announced that Chicagoan Lee B. Thomas, an industrialist with no prior connection to the elevator industry, had been named as president.[6] In the spring of the following year, the company decided to leave the elevator field, and White “purchased American’s inventory of elevator and signal equipment along with their patent rights, patterns and drawings.”[2] In December 1948, White founded the K.M. White Company in partnership with William C. Major (who had been employed in American’s elevator department) and Margaret M. Wrocklage.[7] Regrettably, very little is known about Wrocklage and her role in the company’s creation and operation.

K.M. White was not, however, founded to manufacture elevators. White advertised his company as designers and builders of custom elevator control and signal systems. His immediate success was such that in 1951 he was included in a group that was “given the opportunity of presenting product information” at the second annual meeting of the National Association of Elevator Contractors (NAEC).[8] The following year, he was a founding member of the newly created NAEC Associate Members group, and in 1953, ELEVATOR WORLD founder William C. Sturgeon asked White to serve as the “unofficial liaison” between the NAEC Board and the Associate Members.[8] Thus, “in essence, if not in name, he was the first Associate Group chairman.”[8] White was also among the “half-dozen suppliers and a like number of contractors” who promised to purchase advertising in support of the launch of ELEVATOR WORLD.[8] He regularly purchased full-page ads throughout the 1950s, and the content of his advertisements revealed the company’s innovative approach in designing control and signal systems.

An April 1953 ad announced that the Louisville Courier-Journal & Times Building, completed in 1948, featured elevators with corridor and supervisory control systems. This was one of the first references to what became known as White’s “corridor control” system. Apparently developed in 1947, the system allowed passengers to “select their floors from push buttons in the corridor or from the panel inside the car.”[9] By 1954, the system had been further refined, and the in-car floor selector panel had been removed, leaving the corridor panel as the sole means by which passengers selected their destination. Frederick A. Annett, in the third edition of his book on electric elevators, provided a detailed explanation of the corridor control dispatching system:

“Until recently, a waiting corridor passenger pushed a button to call the elevator to the floor. When the car arrived and stopped and the passenger got on, he or she pushed another button for the desired floor. Now a control system has been developed by K.M. White, which is known as corridor control and combines the two calls into one. With this system, all call buttons, one for each floor, are in a panel near the elevator entrance on each floor. Building patrons just push a button in this panel corresponding to the floor they want. If a passenger is on the third floor and pushes a fifth-floor button, this tells the control that this call is for up direction. Then, the car on its up trip stops at the third floor to answer the call. After the passenger gets on and the doors close, the elevator starts automatically and, if a fourth-floor call is not registered, the car goes directly to the fifth floor and stops, and the doors open. After the doors have remained open for a present period to let passengers off or on, the doors close and the elevator continues to answer up calls. When all up calls are answered, the car starts down to answer down calls that have been registered by waiting passengers pressing corridor buttons on different floors. After a passenger presses a corridor button for the floor to which he wishes to go, the elevator carries out his wishes without further effort on his part. This eliminates crowding around to push buttons in the car. A photoelectric control tells the elevator when the passengers are clear of the door. Corridor button is applicable to one- or two-car operation.”[10]

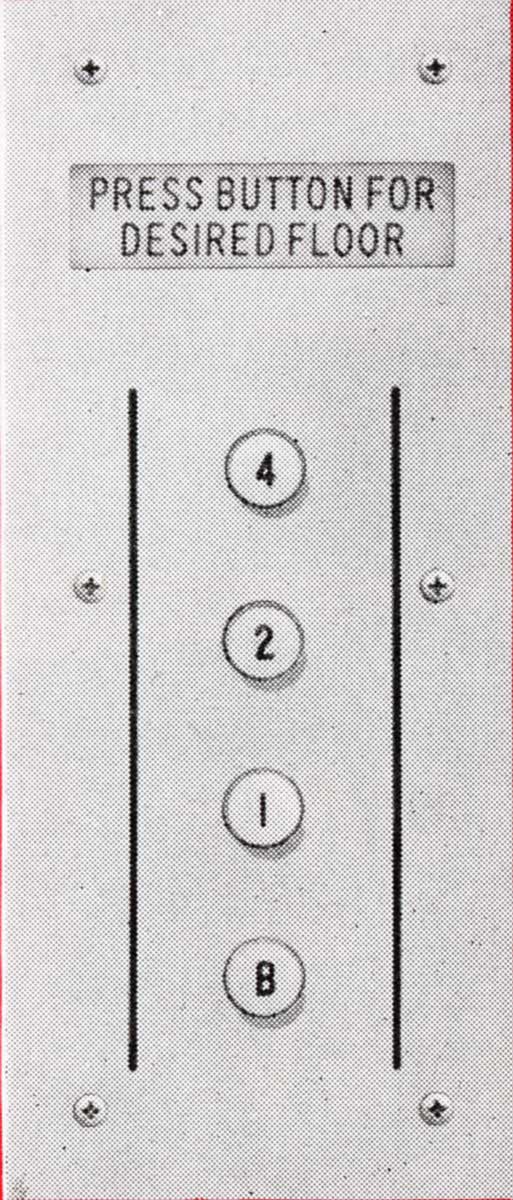

Annett’s description of the system’s operation echoed that found in K.M. White ads, some of which also featured pictures of a typical corridor control panel (Figures 2 and 3). The origin of and inspiration for White’s corridor control system remain unknown. No patents linked to the system have been discovered (although the system was described as “exclusive to K.M. White” in their ads). Additionally, no precedents have been found. Thus, what might be characterized as the first destination dispatch system appeared suddenly – and remarkably – in the American vertical transportation (VT) landscape in the early 1950s.

White also designed a one-of-a-kind elevator system for an addition to Pfeifers’ Department Store in Little Rock, Arkansas, which was advertised as employing a new mode of operation:

“The push button world is as dated as a Model T when a passenger steps inside one of the two elevators in the new Pfeifers of Arkansas building. The difference between this type of operator-less elevator and others is that buttons do not have to be pressed in the corridor or in the car. The passenger merely has to step into the car going in his direction and get off at the desired floor. The elevators stop at each floor in the direction of their travel, reverse at the top floor and repeat the procedure on down to the first floor again, which makes waiting time almost negligible for passengers.”[11]

Samuel Strauss, president of the Pfeifers’ chain of stores, was credited with suggesting this system, which (unknown to Strauss) was similar to some 19th century systems of operation. The key difference was that Pfeifers’ elevators were automatic (no operators). This system, and other innovative approaches to elevatoring, were marketed by White as representing a distinctly “modern” mode of travel, which was overtly linked to the new international style of modern architecture that was appearing in American cities (Figure 4).

As a complement to corridor control, a K.M. White team composed of White, John J. Drexler and Paul Duckwall III developed a patented traffic control system that was marketed as Traffic Master (Figure 5). As was the case with many elevator patents, the inventors provided a summary of the current state-of-the-art in their introduction:

“A great variety of dispatching and control systems for a plurality of elevator cars operating in a bank are in use in modern elevator installations. In many of these systems, cars operating with and without attendants are dispatched from dispatching floors either at predetermined intervals of time or immediately upon arrival at the dispatching floor, and travel either from one terminal to another or are reversed at some point intermediate the terminals, in accordance with the selected one of a plurality of fixed predetermined traffic programs. The particular traffic program is either manually selected by a starter or other system attendant, or is selected during particular hours of the day by a clock mechanism. During nighttime or periods when the bank of elevators is not used except for irregular and intermittent service, it is common practice to shut down the dispatching system and operate only one or two cars on selective collective operation.”[12]

The K.M. White system was predicated on eliminating preset and predetermined patterns of operation to provide a system that automatically adapted itself to varying traffic demands:

“In accordance with the invention, a novel and improved fully automatic dispatching and control system is provided, which operates under all traffic conditions at any time of day or night to instantaneously respond in the most effective manner to satisfy the traffic demand registered in the system at a particular time, independent of any limited number of traffic programs. Traffic demand sensing means is provided, which is at all times responsive to the demand for travel by the cars operated in the bank and the position and direction of travel of the cars, to control the dispatching of cars from the dispatching floors, the direction of travel and operation of the cars, the automatic starting up and shutting down of the driving means for each of the elevator cars in accordance with the number of cars required by the traffic demand registered in the system at that time, and the selection and maintenance of the selection of cars for special and preferred services.” [12]

The Traffic Master system, coupled with Corridor Control, effectively positioned K.M. White as a leader in elevator control system design and innovation.

However, the VT future hinted at in these systems, particularly as represented by Corridor Control, was never fully realized. White died unexpectedly on October 3, 1957, at the age of 54. Had he lived, it seems likely that he would have continued to perfect his unique dispatching system and thus, perhaps, would have changed the industry’s trajectory and fundamentally altered the paradigm of the operator-less elevator. Regrettably, White never had the opportunity to pursue this dream. The VT industry also failed to recognize the opportunity presented by this innovative system. The future had arrived too suddenly and too early. And we missed it.

References

[1] Kenneth M. White and George K. Hearn, Motor-Control System, U.S. Patent No. 1,884,446 (October 25, 1932); Kenneth M. White, Soundproof Base for Machines, U.S. Patent No. 1,922,184 (August 15, 1933); Kenneth M. White and Luther J. Kinnard, Elevator Control System, U.S. Patent No. 1,931,564 (October 24, 1933); Kenneth M. White, Elevator Compensating Rope Sheave, U.S. Patent No. 1,944,772 (January 23, 1934); Kenneth M. White, Elevator Control System, U.S. Patent No. 2,005,878 (June 25, 1935); Kenneth M. White, Control System, U.S. Patent No. 2,069,510 (February 2, 1938); Danilo Santini and Kenneth M. White, Control System, U.S. Patent No. 2,094,377 (September 28, 1937); Kenneth M. White, Timing System, U.S. Patent No. 2,100,726 (November 30, 1937); and Danilo Santini and Kenneth M. White, Regulating Apparatus, U.S. Patent No. 2,128,056 (August 23, 1938. Note: all patents were assigned to the Westinghouse Electric elevator Company.

[2] “Kenneth M. White Obituary,” Elevator World (December 1957).

[3] “Roland I. Phillips Obituary,” Louisville Courier-Journal (July 14, 1954).

[4] Kenneth M. White, Variable Voltage Elevator Control, U.S. Patent No. 2,313,607 (March 9, 1943) and Kenneth M. White and Harry Hadsel, Elevator Signaling System, U.S. Patent No. 2,372,348 (March 27, 1945).

[5] Kenneth M. White and Harry Hadsel, Elevator Signaling System, U.S. Patent No. 2,372,348 (March 27, 1945).

[6] “Elevator Firm Picks Chicagoan as President,” Louisville Courier-Journal (August 21, 1947).

[7] “Charters Granted,” Louisville Courier-Journal (December 2, 1948).

[8] William C. Sturgeon, “History of the National Association of Elevator Contractors 1950-1981,” Elevator World (1982).

[9] K.M. White Advertisement, Elevator World (April 1953).

[10] F.A. Annett, Elevators, Third Edition, New York: McGraw-Hill (1960).

[11] “Pfeifers’ Operatorless Elevators are Unique: Little Rock Department Store First to Feature Development,” Elevator World (January 1956).

[12] Kenneth M. White, John J. Drexler, and Paul Duckwall, III, Elevator Dispatching and Control System, U.S. Patent No. 2,854,096 (September 30, 1958).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.