A fascinating chapter of moving sidewalk history

by Dr. Lee Gray, EW Correspondent

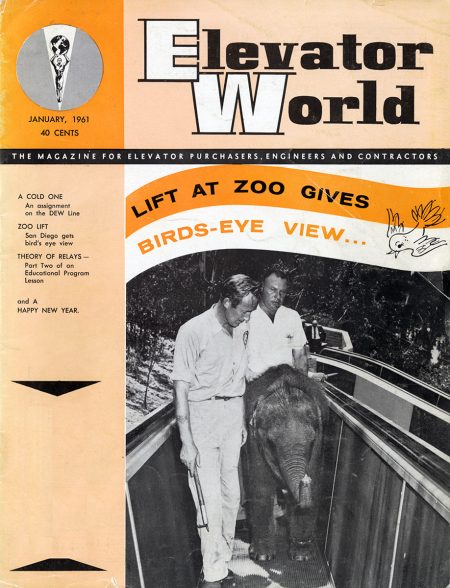

When subscribers received the January 1961 issue of ELEVATOR WORLD they may have, at first glance, wondered if they had mistakenly received an issue of National Geographic. The reason for this possible confusion was the cover photograph and its accompanying caption: “Lift at Zoo Gives Bird’s-Eye View” (Figure 1). The photograph featured Ellie, a baby Indian elephant flanked by zookeeper Jack Perkins and Children’s Zoo Superintendent John Muth. Nineteen-month-old Ellie had arrived at the Balboa Park Zoo in San Diego on April 13, 1960, and was the first baby elephant in Children’s Zoo.[1]

She quickly became popular with zoo visitors, and this popularity doubtless led to her participation in a special event that occurred on July 21, 1960. The event was the official opening of the zoo’s new moving sidewalk system (composed of two moving walkways). Ellie, accompanied by Perkins and Muth, was one of the system’s first riders — an event memorialized in the EW cover photograph. A contemporary account of the event reported that: “Ellie seemed to enjoy the trip, but the sidewalk did not. As the elephant neared the summit of the first of the sidewalk’s two sections, the sidewalk stopped. Officials said the temporary stoppage was caused by a switch being knocked off kilter.”[2] Given that Ellie weighed approximately 400 lbs, and assuming an estimated combined weight of 350 lbs for her human companions, it is, perhaps, not surprising that the resulting “point load” of 750 lbs on the walkway caused a problem.

The moving sidewalks were, of course, not installed to serve as a means of transporting Ellie (or any other zoo inhabitant). A clue to their purpose is found in the account of Ellie’s ride, in which it was reported that the stoppage occurred near “the summit” of the first walkway. The two walkways were, in fact, described as the solution to a serious zoo problem. The exhibits at Balboa Park are not merely caged, like they are at most zoos, but enjoy a home atmosphere nearly “in the manner to which they were accustomed” as possible … This type of layout takes up a lot of space and covers an area that can be walked and climbed only by the best of hikers. Senior citizens, ladies in high heels, handicapped persons and small children found it difficult to climb back up to the upper area, if they had the courage to make the lower rounds at all.[3]

The walkways provided access from “the bottom of Bear Canyon to the Monkey Mesa,” and riders were “elevated 60 vertical feet over a distance of 312 feet.”[3] The first moving sidewalk was 172 ft long and traveled in a southeast direction up a 10˚ incline from the base of the hill to an intermediate platform. The second moving sidewalk was 140 ft long and traveled north, up a 13˚ incline to the top of the slope. The sidewalks operated at a speed of 120 ft/min and had an estimated combined capacity of 3,600 riders an hour. The final project cost was US$150,000.

The idea of employing moving sidewalks as the solution to the zoo’s “transportation problem” had been presented to the zoo’s Board of Trustees by Dr. Charles R. Schoeder, the zoo’s managing director, as one of two proposed innovations (the other was a new bird sanctuary called the Rain Forest). The sidewalk project was inspired by the successful installation of two moving sidewalks at the Tomorrowland exhibit at Disneyland in June 1959.

The Disneyland sidewalks were produced by the Stephens- Adamson Manufacturing Co. Stephens-Adamson was the first American company to produce moving sidewalks, and they manufactured Speedwalks (for horizontal travel), and Speedramps (for inclined travel). Stephens-Adamson built the walkway machinery and supporting structures; the belts that carried riders were manufactured by Goodyear.

The zoo’s Speedramps utilized a slider-belt construction system: In slider-bed installations the belt is supported by a continuous bed of panels of laminated construction. Each panel is made up of a sheet of resin-bonded plywood to which is bonded a stainless-steel sheet on top and galvanized steel sheet on the underside. This provides strong, durable and vibration-damping support for the belt. The stainless-steel top sheet is very highly polished, resulting in friction being reduced as much as possible. So the belt slides easily on the polished bed, there is an additional ply of “silver hard” cotton bonded to the underside of the canvas belt carcass.[4]

The moving sidewalks were, of course, not installed to serve as a means of transporting Ellie (or any other zoo inhabitant).

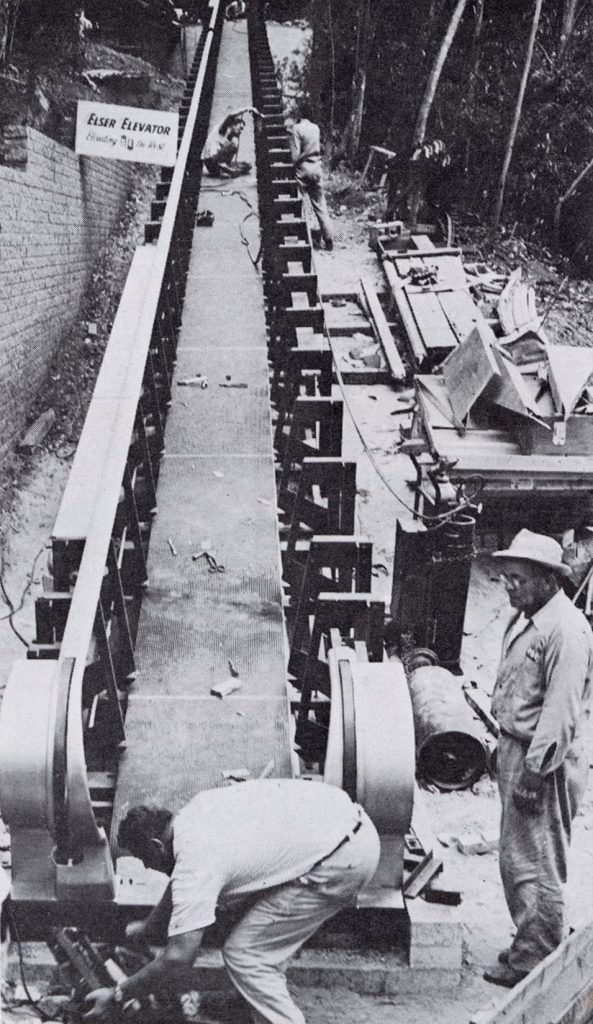

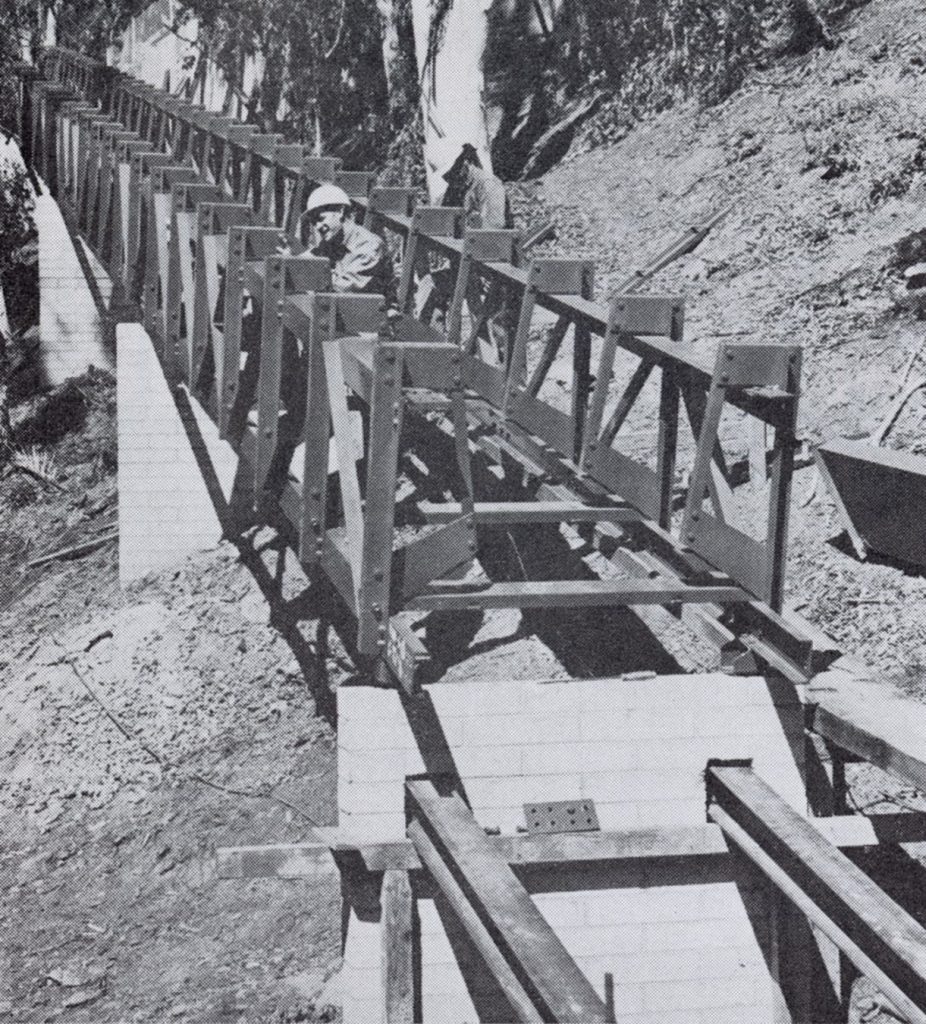

The zoo installation involved three partners: Stephens-Adamson, Goodyear and the Elser Elevator Co. of San Diego. The Elser Elevator Co. was founded in 1931 by William P. Elser (the company’s original name was the San Diego Elevator and Electric Co.; it was changed to the Elser Elevator Co. in 1956). In 1958, the company was acquired by the Montgomery Elevator Co. of Moline, Illinois.[5] Montgomery had an established relationship with Stephens-Adamson, serving as an installer of their Speedwalk and Speedramp systems. Elser’s installation of the zoo’s Speedramps was the subject of local press coverage, which resulted in numerous photographs of the ongoing work (Figures 2 and 3). A specialist from Goodyear also played a critical role in the installation. Moving sidewalk belts are, of course, “endless” in that they continuously revolve around and along the sidewalk’s machinery. Thus, the creation of an endless surface requires the joining, or splicing, of two ends of a walkway belt. The “belt splicer” assigned by Goodyear to the zoo project was Thomas Barr.

Barr was born in Scotland and later resided in Winnipeg, Canada, for 12 years prior to coming to Los Angeles in 1924, where he was employed by Goodyear. His first 20 years of service were in the accessories department. In 1944, he transferred to the Industrial Products division where heultimately became a master belt slicer.[6] He retired in 1963 after a 39-year career with Goodyear, working 19 years as a belt slicer (the numerous projects Barr worked on included the Disneyland Speedramps).

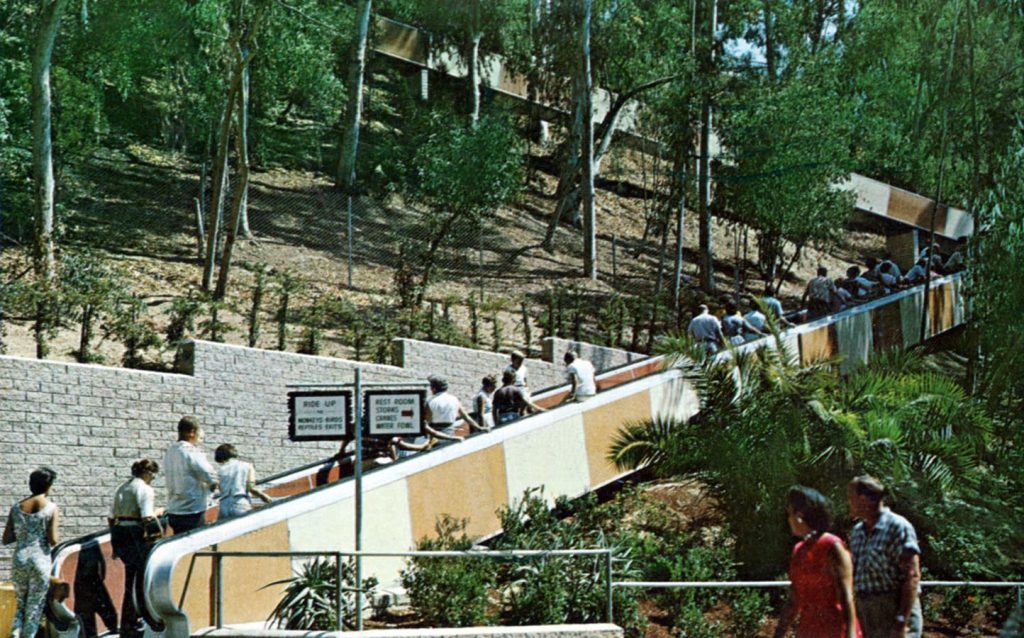

The zoo’s Speedramps quickly gained national attention. The March 5, 1961, edition of the syndicated column “Strange as It Seems” featured a cartoon-like drawing of the ramps with the caption: “Speedramp — A 312-foot-long conveyance capable of carrying 3,000 visitors per hour at the San Diego Zoo, is the longest moving sidewalk in the world!”[7] The claim of being “the longest in world” was true — but only if the lengths of the two sidewalks were added together. In 1961, the longest moving sidewalk in operation was the sidewalk installed in the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Co.’s Erie Station in Jersey City, New Jersey (a Stephens-Adamson Speedwalk that was 227 ft long). The black-and-white photograph that served as the basis for the “Strange as It Seems” drawing was taken from the vantage point of the intermediate landing. This image captured the dramatic character of the system as riders pivoted between the Speedramps (Figure 4).

The system was also the subject of a popular postcard often purchased by visitors to the zoo. The color photograph on the postcard, taken from the base of the first Speedramp, complements the black-and-white photograph in highlighting the dynamic character of the system as it climbed the slope (Figure 5). The system was also linked to a uniquely regional cultural phenomenon: “California, long recognized as a pioneer in superhighway systems, claims another first with its “pedestrian freeway.”[8]

On May 30, 1967, the zoo held a ceremony opening a third Speedramp.[9] This event, however, lacked the dramatic impact of having Ellie as one of the first riders. By this date she was an adult elephant and, as she “tipped the scales at nearly 3,00 pounds,” her riding days were clearly over (and had been over for some time).[10] In fact, Ellie could not have ridden the new Speedramp even if it had been engineered to support her weight. On April 4, 1961, Ellie was transferred to the Calgary Zoo in Canada. Thus, Ellie the elephant’s arrival and departure serve as unique bookends to this chapter of moving sidewalk history.

References

[1] “Canada Zoo Gets ‘Ellie’ the Elephant,” Escondido Daily Times- Advocate (April 5, 1967).

[2] “Rain Forest, Ramp Give Zoo Lift,” San Diego Evening Tribune (July 21, 1960).

[3] “Zoo With an Elevator,” Long Beach Press-Telegram (September 11, 1960).

[4] John M. Tough & Coleman A. O’Flaherty, Passenger Conveyors, London: Ian Allan (1971).

[5] “’Round the Elevator World: Montgomery on the Move,” EW(March 1959).

[6] “Barr Now to Have Time for Fishing, Woodwork,” South Gate Press (July 18, 1963).

[7] “Strange as It Seems” appeared in newspapers published across the U.S.

[8] “Visitors to San Diego Zoo Get Help on Hills,” Colton Courier (September 14, 1960).

[9] “San Diego Zoo Turns on Moving Ramp,” Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (May 30, 1967).

[10] “Canada Zoo Gets ‘Ellie’ the Elephant,” Escondido Daily Times-Advocate (April 5, 1967).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.