ELEVATOR WORLD in 1983

Jul 6, 2023

Magazine becomes increasingly international, adds events calendar and covers computers.

While ELEVATOR WORLD’s editorial mission, first defined by founder William C. Sturgeon in 1953, remained essentially unchanged as the magazine entered its 30th year, long-time readers doubtless noticed a few important differences. One of the most obvious was the increased presence of features and columns that concerned the international vertical-transportation (VT) industry. In fact, by 1983, EW’s global presence was well established. The magazine had 13 foreign correspondents and had established partnerships with 29 VT industry organizations from around the world. The international connection was also reinforced by an ongoing series first introduced in March 1981. The “new” series was the re-publication of Paul Kern’s column, “Rail Clips and Call Backs,” which appeared from 1955 to 1968. The revival of these columns was made possible by a new piece of technology, the EditWriter 7300, which featured an expanded range of font types — including Spanish. Sturgeon had partnered with Cruz Trujillo (Elevadores Villares in Mexico City) to translate Kern’s columns into Spanish. He hoped that this initiative would prove useful to the magazine’s “growing number of readers in Latin America” and thus, “hopefully … bring another group of elevator men into the Elevator World family.”[1]

Other changes included new columns that had been introduced over the past decade. The column “Codes and Standards,” which reported on the work of the A17 code committees, first appeared in November 1979 with David Wizda serving as the primary author. “From the Inspectors Viewpoint” first appeared in April 1982. Sturgeon introduced one of the column’s primary authors in his announcement of the new feature: “Ken Myhre, recently retired as the chief elevator inspector of Seattle, has volunteered to edit a column which will crystalize information received from members of the National Association of Elevator Safety Authorities (NAESA) that might have interest for the total industry.”[2] Joining Myhre as a co-lead-author in the series was D. Allen “Dee” Swerrie, a California State elevator inspector, who was also an NAESA member.

A new feature that debuted in 1983 was a calendar of industry events titled “Staying on Top.” In his “editor’s note” to the inaugural column, Sturgeon reported:

“In an effort to keep the industry informed we invite all associations to send us information concerning up-coming meetings, seminars, exhibits, workshops, golf and tennis outings, etc. The published information will serve as a reminder to those who should attend, those who might want permission to attend or who wish to present information for the consideration of attendees. Send Elevator World your association’s schedule of meetings with as much descriptive information as possible.”[3]

While the calendar primarily provided information on events in the U.S. and Canada, it also listed international events. The January issue calendar included an announcement for the Salon International de Construcción, an international building exhibition scheduled for March 1983 in Barcelona, Spain.

The February issue featured the first of a 14-part series by Paul K. Smith titled “The Mathematics of Maintenance,” which appeared in the “Contact” column.[4] The series concerned a systematic approach to determining maintenance costs, which used 14 key factors: rated capacity, rated speed, number of openings served, number of cars considered, general condition of equipment, door system, motor control, door operation, door operator and interlocks, controller, desirability (attractiveness), type of coverage, escalation and proration (each article in the series addressed a different factor). Smith’s VT career included stints with Westinghouse, the Sedgwick Machine Works, W&H Conveyor Systems and Mainco. Although he had retired in 1977, as was the case with many “retired” engineers, he continued to work as a consultant. Smith was, of course, only one of the numerous retired or senior industry members who regularly contributed to EW. One such figure was the subject of an “exclusive interview” published in March.

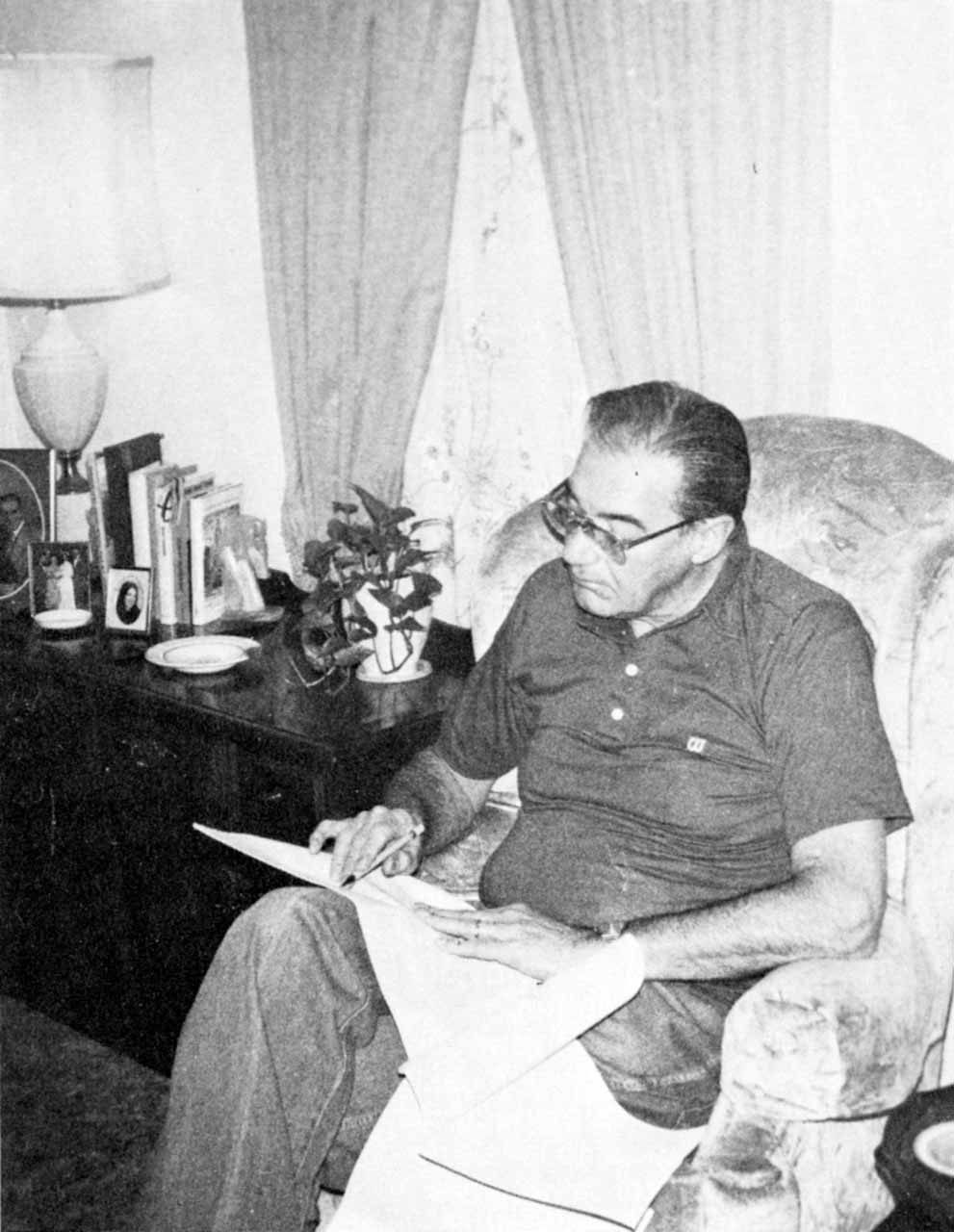

Sturgeon traveled to NYC in early 1983 to interview industry veteran George Strakosh (Figure 1). The interview was prompted by the publication of the second edition of his pioneering work Vertical Transportation: Elevators and Escalators (the first edition appeared in 1967). Strakosh’s career-to-date was summarized as follows:

“Currently Strakosch is an Associate in Vertical Transportation and Material Handling for Jaros, Baum and Bolles Consulting Engineers in New York City. Previously he worked for Otis Elevator Company in a variety of positions, rising from Elevator Constructor to Manager of Special Projects, including Irving Trust Co., the Continental Corporation Center, and the new Phillip Morris Headquarters building in NYC. Earlier in his career he was involved in unique elevator applications for the Hemisfair Tower in San Antonio, Texas; the Canadian National Tower in Ontario; the World Trade Center in NYC; the Sears Tower and the John Hancock Tower in Chicago; and glass elevators for numerous hotels. In addition, he has supervised special elevator installations at the Cape Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and design of stage lifts for MGM hotels.”[5]

The interview covered a broad range of topics, from the origin of the book’s first edition to the challenges of updating the contents in a rapidly shifting VT landscape. The current and future anticipated pace of change doubtless led to Sturgeon’s final question: “What do you see as major problems in the next ten years?” Strakosch’s answer reflected his broad range of industry experience:

“The training of all kinds of specialists: application engineers, field technicians, and sales engineers. Just think of what field maintenance personnel are faced with — they may leave one job with copper contacts to walk into one with a microprocessor. Innovations are coming on stream all the time.”[5]

This response also hinted at a topic that was evident in much of EW’s industry coverage during 1983: computers. The coverage of computers and computer-related technology included articles designed to introduce new technologies and speculate on their impact, articles that described the actual application of these technologies to elevator systems and articles that described the application of these technologies to elevatoring or elevator planning. Elmer Sumka and John De Lorenzi (Westinghouse) offered readers an introduction to solid-state technology and its application to VT systems. They noted that the initial application of solid-state components had a dramatic impact on elevator drive systems:

“The first major change impacted by solid-state was in the area of rotating equipment. A conventional motor generating set’s purpose is to utilize the AC line power to drive an AC motor. The AC motor then mechanically rotates a DC generator to generate DC power. The DC power, in turn, drives a DC motor to power the elevator hoist motor. This system is still utilized in many applications today. With the development of solid-state, it became apparent that there was no need to go through two stages of power generation. It was possible to go from AC to controlled DC through the use of power semiconductors and sophisticated electronic control. The result was the development of solid-state motor drive for elevators.”[6]

This practical example was followed by a discussion of the development of the microprocessor, and the authors’ wondered:

“Where will this explosion in micro computer technology take us? What does it mean to the elevator industry? Can we expect the same type of innovation for elevator systems that has happened to the calculator and home computer fields? With this new computer technology and the ever-increasing memory and computing capabilities, new opportunities for elevator systems are unlimited. Elevator companies will be in the business of making standard hardware brains with tremendous memory capability to be programmed according to the designer’s imagination — not hardware limitations.”[6]

Sumka’s and De Lorenzi’s speculations on what the future might hold included one accurate predication and one that has yet to be realized. They anticipated that “the ability of the computer to gather, store and process large amounts of data” offered the opportunity to “continuously monitor elevator performance. It would be almost like having a maintenance mechanic for every car, 24 hours a day.”[6] Their less accurate predication concerned voice recognition control:

“A corridor call could be registered by issuing a verbal command for the ultimate destination, such as 10th floor. The corridor push button box could answer: The car behind you to the right will take you to the 10th floor.”[6]

It is interesting to note that the cartoon-like illustrations that accompanied their paper resembled 35 mm slides (their article may have been initially developed as a presentation for Westinghouse engineers) (Figures 2 and 3). The mix of digital subject matter with decidedly analog illustrations serves as a reminder of the dynamic nature of this early stage in computerization.

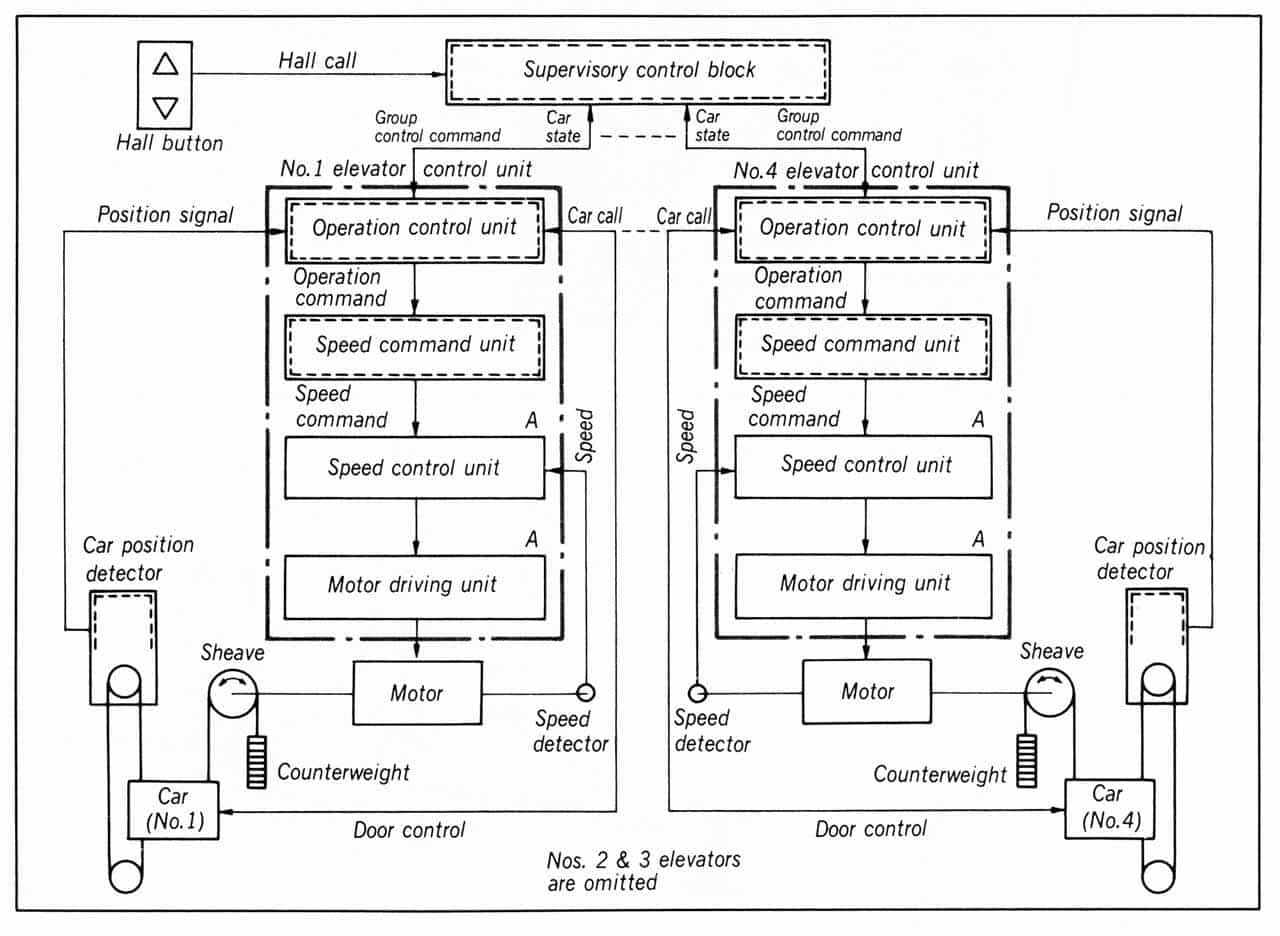

A distinct counterpoint to Sumka’s and De Lorenzi’s speculative piece was an article by Japanese engineers Masao Nakazato, Takasi Kaneko and Seiya Shima (Hitachi Mito Works), which provided a detailed description of Hitachi’s new solid-state microprocessor-controlled DC elevator:

“The application of microprocessors to elevator control started with the automatic group supervisory control systems used to control the operation of more than one elevator. In recent years, the application of microprocessors has extended to individual elevator control in standardized mass-produced elevators. Meanwhile, there is increasing demand for elevators that conserve energy, allow efficiency of transport facilities in buildings. This trend is most pronounced in large office buildings and multistoried hotels which use DC elevators. Hitachi has responded to the market by developing a fully solid-state elevator system using microprocessors with up-to-date electronic and computer control techniques.”[7]

The article explained the overall configuration, hardware and general features of Hitachi’s solid-state system (Figure 4).

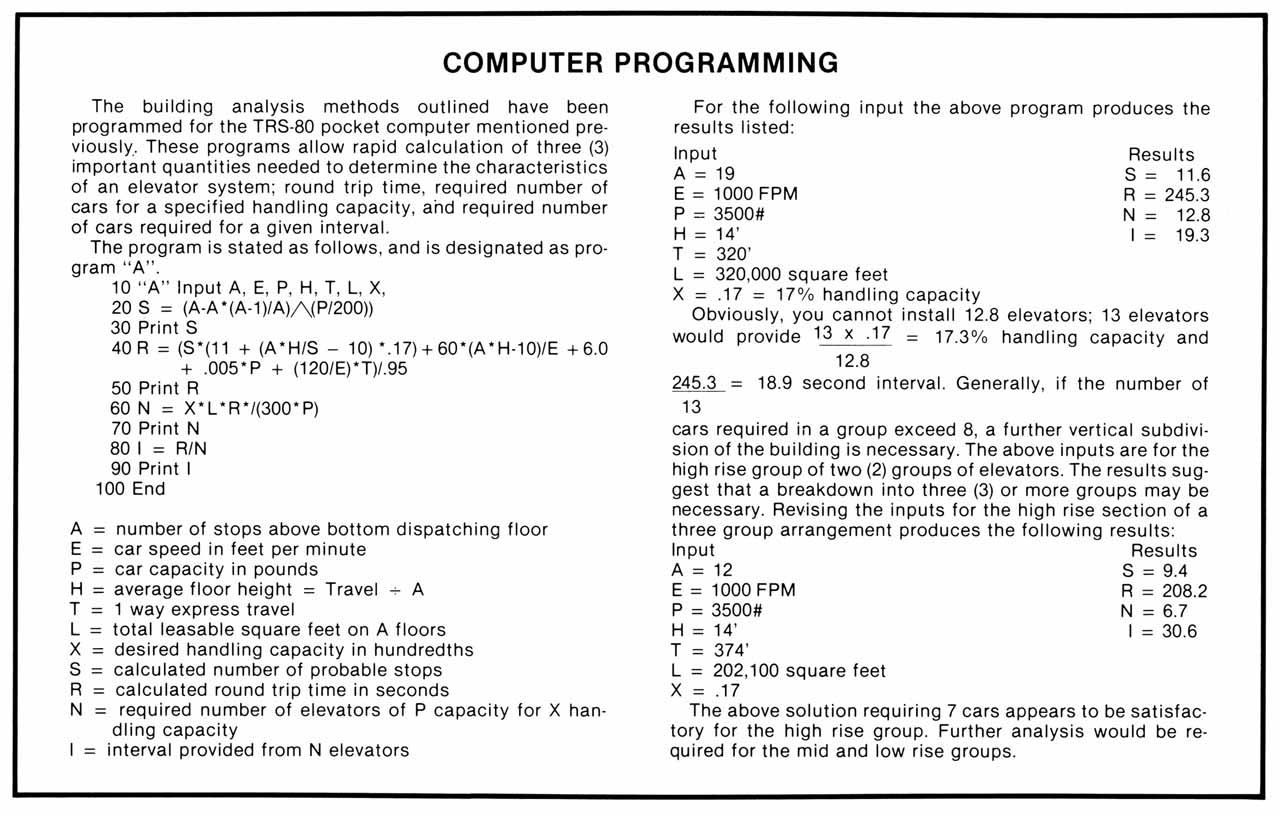

An article by industry veteran Jack T. Edwards (Dover) provided a summary of the “basic principles commonly utilized in estimating the elevator requirements for office buildings” and how these could be utilized to program a pocket computer to estimate system needs. Edwards used a Tandy TRS-80 computer (sold by Radio Shack) for his calculations. The computer measured 6.875” x 2.75” x .7”, weighed 6 oz. and employed two 4-bit processors with 11K of ROM (for BASIC) and 1.9K of RAM (for user programs). It featured a 24-character LCD display (uppercase characters only) and had a 57-key QWERTY keyboard. Edwards noted that, while “compromises are necessary in the programming due to the limited capabilities of pocket computers, the results obtained are generally within ± 5% of those obtained from larger units.”[8] Edwards published this program designed for use on the TRS-80 and reported that it allowed for the “rapid calculation of three important quantities needed to determine the characteristics of an elevator system: round trip time, required number of cars for a specific handling capacity and required number of cars for a given interval” (Figure 5).[8]

German engineer Dr. Joris Schroeder (Schindler) contributed a two-part article that paralleled Edward’s piece.[9,10] Schroeder observed:

“Elevatoring studies can be very time consuming, if performed without the help of a programmable calculator or a computer. One of the most convenient techniques is based on the use of a pocket computer, preferably with a built-in or attachable printer.”[10]

His computer of choice was the SHARP PC-1251 (also sold in the U.S. by Radio Shack). While he illustrated the results of his programming efforts by reproducing printouts of his results Schroeder, unlike Edwards, did not publish his formula.

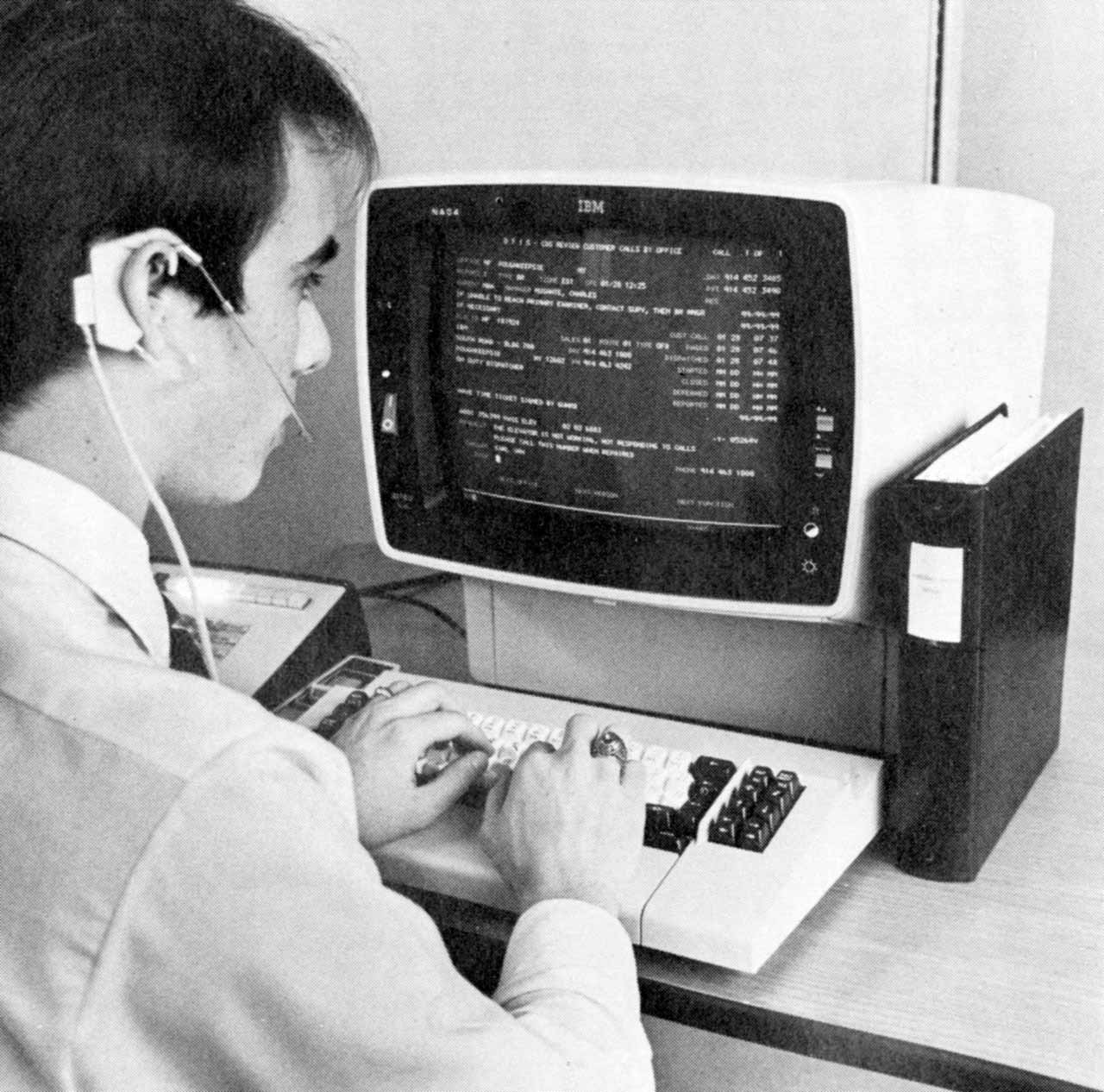

Two final applications that appeared in 1983 were related to the computer’s ability to collect and store large data sets. Early in the year Otis had announced OTISLINE, described as “the industry’s first nationwide maintenance service dispatching service.”[11] Customers calling the service center, located in Farmington, Connecticut, would be connected with a dispatcher who had immediate access to the company’s main computer which contained information on the “number of elevator or escalator units, their type and location … the type of service contract, and any recurring problems the equipment may have experienced.”[11] The initial launch of OTISLINE only covered customers in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia and Virginia. The presence — and importance — of the computer was highlighted in the publicity photographs, which featured a young man entering information into the system (Figure 6).

The other data storage application project was undertaken by EW. In September, Sturgeon’s monthly column, “Speaking of Issues,” was subtitled “Love that Computer.”[12] He recounted, perhaps with a slightly selective memory, that the magazine’s “computerization” had been:

“a relatively serene experience. There has been no need to be pulled, kicking and screaming into the electronic information processing age, probably because we have always been in the business of processing information – only with a pick and shovel, figuratively speaking. When the flat keyboards and screens appeared on our desks, it seemed just another gradual transition — as from the radio to color TV, manual to electric typewriter, photocopier instead of carbon paper.”[12]

The computerization of the magazine’s production was followed by the first data-related project:

“Our initial project — for which we had to develop software — was to place within the computer all editorial material being processed … After articles are published, the information as to title, author and theme are moved into another data field along with a half dozen key words pertaining to the content and a means of identifying the page, issue and volume containing the material. Within the next few years, we will review all issues published since January 1953 and key in similar information.”[12]

An important participant in these efforts was current EW Editor-at-Large Ricia Sturgeon-Hendrick, who was said to be able to “program and play the keyboards like a piano.”[12] In contrast, Sturgeon reported:

“This editorial, like all those of the past 30 years, is being written on a 40-year-old manual Royal typewriter, about 24 inches away from a computer terminal. The old workhorse will never be put out to pasture … But, there is no denying that the adjacent green screen is what will transport our kind of communications business into the future.”[12]

This blended commitment to the past and the present was emblematic of Sturgeon’s approach to his coverage of the VT industry, and was evident in another close-to-home project.

In June, Sturgeon had informed readers about the completion of what was likely a genuine labor-of-love:

“During the past few months, as our staff renovated and stocked the building next door to the Elevator World headquarters with reference material, one asked, ‘Can’t we call it something besides the little house?’”[13]

Visitors to Mobile, especially those who come to do research, know that the “little house” is, in fact, a remarkable library that contains an extensive collection of historical materials associated with the VT industry. In keeping with the theme of old and new, it was fitting the house hosted the first joint meeting of the magazine’s Technical Communications Council (TCC) and Board of Directors. A photograph of the assembled groups reveals a who’s-who of industry leaders, including Sumka (Westinghouse), George Gibson (Otis), George Strakosch (Jaros, Baum & Boles) and Quentin Bates (Lerch, Bates & Associates) (Figure 7).

The 1983 Annual Study, titled “Art/Architecture in Motion,” focused on glass elevators. The study featured a collection of 102 photographs depicting over 75 elevator installations from 19 countries representing North and South America, Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia. In his introduction, Sturgeon asked and answered an age-old question: “Is architecture art? This question has been argued ad infinitum. It is probably a mysterious mix of science, art, and practicality.”[14] He then linked his answer to the VT industry: “Elevatoring, itself, is a science, but designers of fixtures, cabins, and entrances usually think of themselves as artisans of the first order.”[14] This artistry was effectively displayed in the study’s images (Figures 8 and 9 are representative examples of the work included in the study).

There was, however, one aspect of glass elevators (which had been previously introduced in a letter-to-the-editor) which remained unexplored in the Annual Study. In January, Leo Burman (Advance Elevator Service, Inc.) had written to EW about a news item he had found in the November 15, 1982, issue of Time Magazine. The item concerned American actress Jacqueline Bisset and her upcoming movie “Class.” The film featured a scene in which Bisset seduces a young prep school student in a glass elevator. As was noted by Burman: “If couples are transported on waves of ecstasy, as well as from floor-to-floor in scenic elevators, our sales volume might increase correspondingly!”[15] The elevator featured in the movie was one of the glass elevators in the atrium of Chicago’s Water Tower Place, which were illustrated in the Annual Study. The film was released to theaters on July 6, 1983, thus Sturgeon had ample time to make this connection and provide an appropriate comment. In this instance, however, perhaps discretion was the better part of valor.

References

[1] “Speaking of Issues,” Elevator World (March 1981).

[2] William Sturgeon, Introduction, “From the Inspectors Viewpoint,” Elevator World (April 1982).

[3] Editor’s Note: “Staying on Top,” Elevator World (January 1983).

[4] Paul K. Smith, “Contact: The Mathematics of Maintenance” Elevator World (February 1983).

[5] William Sturgeon, “Exclusive Interview with Author George Strakosch” Elevator World (March 1983).

[6] Elmer Sumka and John DeLorenzi, “Elevators and Solid-State Technology,” Elevator World (March 1983).

[7] Masao Nakazato, Takasi Kaneko, and Seiya Shima, “Solid State Microprocessor Controlled DC Elevator” (March 1983).

[8] Jack T. Edwards. “Handheld Computer Traffic Analysis” Elevator World (September 1983).

[9] Joris Schroeder, “Pocket Computer Elevatoring – Part 1: Improving Efficiency with Round-Trip Time,” Elevator World (November 1983).

[10] Joris Schroeder, “Pocket Computer Elevatoring – Part 2: Improving Efficiency with Round-Trip Time,” Elevator World (December 1983).

[11] “’Round the Elevator World: Otis Introduces National Service Dispatching Center,” Elevator World (April 1983)

[12] William Sturgeon, “Speaking of Issues: Love that Computer” Elevator World (September 1983).

[13] William Sturgeon, “Speaking of Issues: It’s the Game; Not the Name,” Elevator World (June 1983).

[14] Elevator World Annual Study: Art/Architecture in Motion (October 1983).

[15] Leo Burman, “Comments: A Plus for Scenic Elevators,” Elevator World (January 1983).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.