1927 Smith, Major & Stevens Specification & Tender (Part 1)

May 29, 2024

A look at the firm’s origins leading up to 1927

The survival of a 1927 specification and tender for an electric goods lift, prepared by Smith, Major & Stevens, Ltd. for the Atlas Works (Shrewsbury), provides a unique opportunity to examine vertical-transportation (VT) industry business practices in the late 1920s (Figure 1). However, prior to examining this document, it is necessary to first explore the history of Smith, Major & Stevens, which by this time had established itself as one of the country’s leading lift manufacturers. They also claimed to be one of the oldest such firms. Beginning in the late 1860s, they advertised themselves as having been “established upwards of a century.”[1] By the early 1900s, they had identified a specific origin date, claiming to have been “established in London in 1770.”[2] This story begins with the search for the firm’s origins.

The search began by starting in 1927 and following the historical record backwards. Unfortunately, the trail ended in the early 1800s, and no link to 1770 was found. Thus, our story begins in 1798 (or possibly 1800) with the birth of Andrew Smith in Fleming, Dumfriesshire, Scotland. No record of his parentage has been found, and the precise date of his arrival in London is also unknown. What is known is that, beginning in the mid-1820s, he was active in the London area, and he moved his business to 69 Princes Street, Leicester Square, Westminster in 1829. This location was to serve as the business’ headquarters until the early 1900s.

Between 1829 and 1854, Smith variously described himself as a merchant, machinist, engineer and civil engineer. He patented a wide range of inventions, which included a popular method for making wire ropes and a variety of building hardware components and systems. In an 1843 advertisement, he noted that his business produced copper wire rope (for use on lightning rods), patent paneled and revolving iron shutters, patent weather-tight fastenings and sill bars for casement windows, patent double- and single-action door springs, improved flooring clamps, patent wire sash lines, iron doors, plain and ornamental palisading, gates and columns.[3]

In addition to his activities as an inventor, Smith was also prolific in another arena. He fathered 10 children between 1825 and 1846, three of whom became successful engineers: William Smith (1825-1878), Archibald Smith (b. 1829) and Andrew Smith Hallidie (1834-1900) who, for reasons unknown, adopted the last name of his godfather and uncle, Sir Andrew Hallidie, a well-known physician. William Smith had a successful career as a consulting engineer and as the editor and proprietor of The Artizan journal. He joined his father’s business as a partner in 1847, remaining for five years. His departure from the shop coincided with his father’s departure from England.

In 1852, Andrew Smith and Andrew Smith Hallidie traveled to California where they joined a host of others seeking riches in the gold fields of Mariposa County. Andrew (the father) had purchased an interest in a mine prior to leaving England, an investment that, upon arrival, quickly proved to be worthless, and he returned home in 1853. Andrew (the son) chose to remain in California. He became a successful civil engineer (specializing in building suspension bridges), and he designed one of the first cable car systems in the U.S.

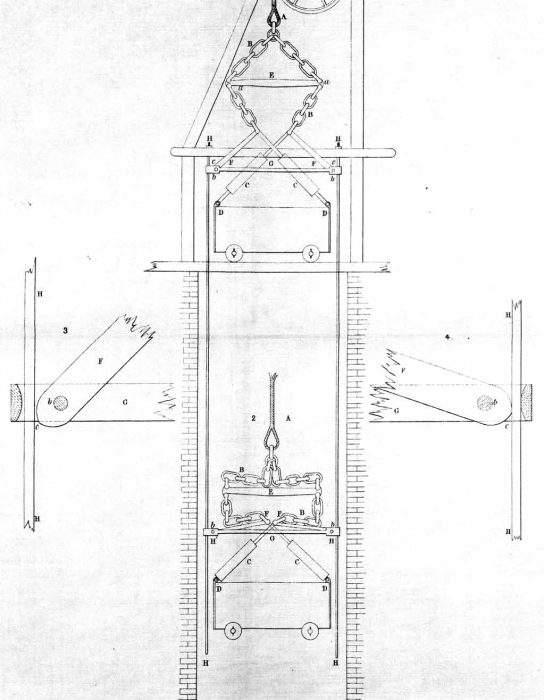

During Andrew Smith’s absence, the shop was run by his son Archibald, who may not have welcomed his father’s return — particularly given the financial failure of his California adventure. In fact, Andrew Smith had a record of poor business management, having previously declared bankruptcy in 1833, 1840 and 1848. While the record suggests that Archibald was the leading partner by this point in time, it also indicates that his father continued his pursuit of new inventions, which led to their first lift-related patent. On 6 October 1854, he filed a patent application titled Miners’ Safety Cage or Car, which was sealed on 30 March 1855. The patent concerned a safety that acted if the hoisting rope broke (Figure 2):

“When the winding rope happens to break … the elastic lanyards C, C, each acting by an internal spiral spring, contract and pull down the levers F, F, into a horizontal position, thereby causing their ends c, c, to press or jamb the eccentric jointed ends against the guide rods or ropes, as represented at H1, H1, thus stopping the further descent of the cage.”[4]

The reasons behind Smith’s pursuit of a mining lift safety are unknown, as this was a clear departure from his previous work. A similar departure was found in a second patent application filed on 21 December 1854, which concerned a steam powered gun.[5] The patent, which was never sealed, included an odd reference to the use of “hydro-electric power,” and it did not embody a well-thought-out design proposal. In March 1859, Smith gave a public presentation on what he now referred to as his “electric gun.” As reported by The Mechanics Magazine, the presentation did not go well:

“After the delivery of Major Rhodes’ lecture on Tents on Monday evening last, at the weekly meeting of the United Service Institution, Mr. Andrew Smith stepped forward to read a paper on an electric gun, which was alleged to be capable of discharging 60 balls per minute with precision. We listened intently, but vainly, for a description of this curious instrument, and Captain Fishbourne, who presided, appealed vainly to the speaker for something more than an unintelligible jumble of known and unknown words.”[6]

The magazine reprinted much of the text of Smith’s presentation, which was, indeed, incomprehensible. This unfortunate event was followed a few months later by one that indicated that Smith’s mental health was, perhaps, declining. As reported by The Sun newspaper: “Andrew Smith, an elderly man … described as an engineer, of 9, Vine-cottages, Lambeth, was charged with breaking nine squares of glass at the house of his son, Mr. Archibald Smith, engineer, of 69, Prince’s-street, Leicester-square.”[7] This marked the last known reference to and appearance of Andrew Smith, who left his son Archibald to literally pick up the pieces and continue his father’s business on his own.

Archibald had, in fact, already begun to establish himself as an independent inventor and to lay the groundwork for a sustainable business. In 1857, he patented a machine designed to manufacture wire rope, thus building on his father’s earlier work.[8] An 1865 advertisement claimed that: “Smith’s patent wire and cable machine (is) guaranteed to produce four times the usual quantity of work, of superior quality, (and) at one-third the cost for labour.”[9] He also claimed that he could provide references from “all the principal rope makers in the Kingdom and on the Continent” and that, in addition to wire rope machines, his shop could provide “every description of machinery and repairs at reasonable prices.”[9] Smith’s success was also such that he was able to expand his work force.

In 1867, Smith hired John Sanders Stevens (1844-1903). While nothing is known about Stevens’ engineering-related training or education, his early career did not appear to position him for success as a mechanical engineer. In fact, his only known obituary, which memorialized John Sanders Stevens, F.E.S., did not appear in an engineering publication. The abbreviation “F.E.S.” identified Stevens as a Fellow of the Entomological Society of London, and his obituary appeared in The Entomologists Monthly Magazine.[10]

He had joined the Society in 1862 and had worked as an assistant to his uncle, Samuel Stevens, who operated a Natural History Agency in London. The closure of the agency marked Stevens’ transition from the world of entomology to that of industry. Although members of the VT world are well aware that individual paths into the industry are often not straightforward, this may be one of the most unique paths traveled. It also raises questions about Smith’s ability to appraise future employees. In this instance, Stevens very likely exceeded his expectations, and in 1869, Smith changed the company’s name to Archibald Smith & Co., reflecting Stevens’ contributions.[11]

Although no evidence exists that suggests that Stevens was solely responsible for company’s entry into lift manufacturing, evidence does exist that indicates that they entered this emerging marketplace in the early 1870s, with the first advertisements for their lifts appearing in 1876:

“Archibald Smith & Co.’s improved patent lifts and hoists for private houses, eating houses, dining saloons, clubs, hotels, railway stations, shops, offices, banks, hospitals, warehouses, auction rooms, schools, barracks. Every lift guaranteed. Made noiseless when required. A. S. & Co.’s patent safety apparatus fitted to existing lifts. Hundreds now in use in all parts of London. Further particulars and drawings on application.” [12]

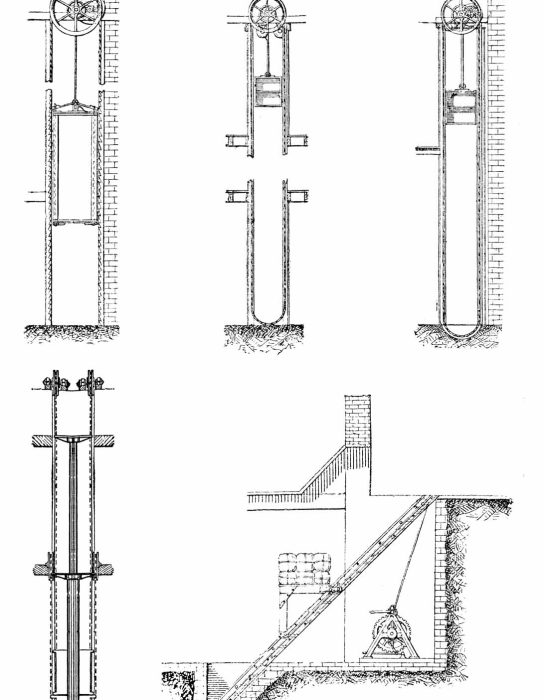

Each advertisement was accompanied by a single illustration, typically of a hand-powered lift. Their full range of lifts was on display in the 1876 issue of Spon’s Engineer’s and Contractor’s Illustrated Book of Prices of Machines, Tools, Ironwork, and Contractors Material. Two of the six pages devoted to products manufactured by Archibald Smith & Co. described and illustrated their improved warehouse and hospital lift, improved hydraulic lift, small dinner and house lift, improved cellar hoist, and large dinner or house lift (Figure 3).[13]

More evidence of Stevens’ importance to the business’ success appeared in 1877, when the company’s name was changed to Archibald Smith & Stevens. The name change first appeared in advertisements for their hydraulic, steam and hand power lifts.[14] The following year, Smith and Stevens welcomed Charles George Major (1851-1917) to the company. Major was born in Basingstoke, were he attended the local British school. He then apprenticed for six years at a local iron works, which was followed by work as a draughtsman at Henley’s Telegraph Works (North Woolwich) and at Messrs. R. Warner and Co., hydraulic engineers (Walton-on-the-Naze). In 1877, he became manager of Messrs. Withinshaw and Co., rolling mill and colliery engineers (Birmingham), after which he joined Smith & Stevens as shop manager. His arrival marked the beginning of a dynamic design partnership with Stevens that served as the driving force behind the company’s future commercial success.

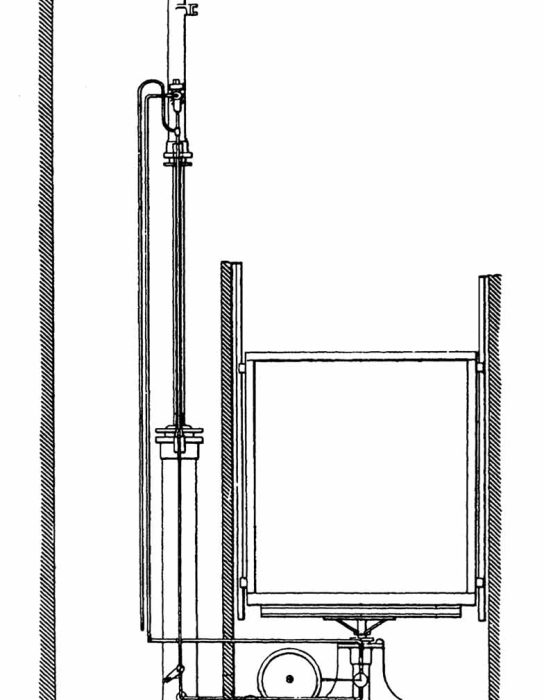

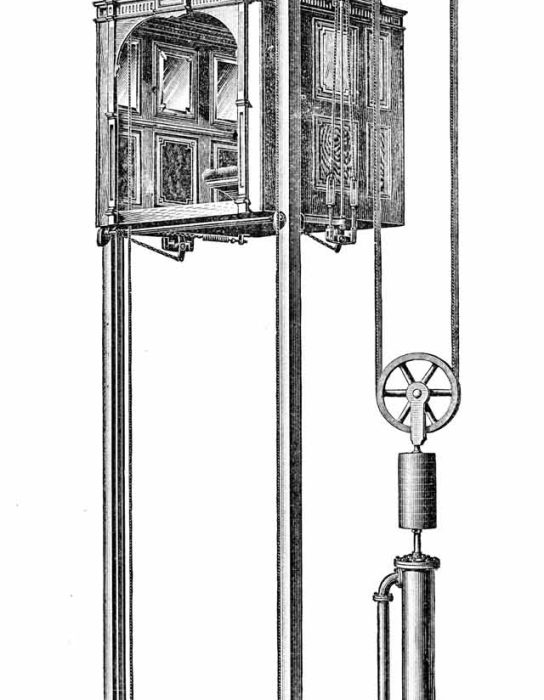

In 1881, Stevens and Major received the first of their 26 lift-related patents.[15] The patent, for a balanced hydraulic lift, concerned a direct-action lift that employed an accumulator (Figure 4). Their pursuit of design improvements led them to develop a suspended hydraulic system (which followed trends in the U.S. and England) that was introduced in 1888 as Stevens and Major’s “Reliance” Hydraulic Lift.[16] Versions of this lift remained in production throughout the 1890s (Figure 5). In 1895, Smith & Stevens claimed that more than 300 Reliance lifts had “been supplied in all parts of the world for public buildings, hotels, hospitals, offices, residential flats, private houses, etc.”[17]

Stevens and Major may have been aided in their design efforts by the addition of Stevens’ two sons to the Smith & Stevens workforce in the 1880s. Edwin Charles Stevens (1873-1952) and Percy Herbert Stevens (1878-1941) both began their academic careers at New College, Eastbourne. Edwin also attended the Moravian School in Neuwied-on-the Rhine, Germany, prior to beginning work as an apprentice at Smith & Stevens in 1889. By 1891, he was working as a draughtsman; in 1893, he was made a superintendent; and in 1896, he became a partner. Between 1889 and 1893, he also attended lectures at Kings College, London and at Finsbury Technical College (London). Percy began at Smith & Stevens in 1894 serving as an assistant to his father in the general operation of the company. For a brief time, he also attended classes in mathematics and engineering at Finsbury Technical College. Major’s son, Percy Charles Major (1883-1950), joined the company in the early 1900s, thus solidifying the company’s “family centric” leadership structure.

The company’s entry into the new century was accompanied by the expansion of their product line to include electric lifts. While they had doubtless been experimenting with these lifts in the 1890s, in 1903 they produced an illustrated catalog that described their “new list of electric lifts” and provided information on the advantages of using electric versus hydraulic lifts (Figure 6).[18]

1903 also saw the death of John Sanders Stevens. A brief announcement of his death, which appeared in The Engineer, noted that: “The business will be carried on by the surviving partners, Mr. C. G. Major, and E. C. and P. H. Stevens, the sons of the deceased.”[19] The absence of Archibald Smith’s name from this announcement is curious. Equally curious was the fact that, when the company changed its name in 1909 to reflect Major’s contributions, Smith’s name was once again left out of the press coverage:

“The well-known firm of lift engineers, Messrs. Archibald Smith and Stevens have just converted their business into a limited company, under the title of Smith, Major and Stevens, Ltd. The directors are Messrs. E.C. Stevens, P.H. Stevens, P.C. Major, and C.G. Major, the last-named gentleman being chairman. The change has been effected for family reasons only, and no shares are offered to the public.”[20]

Lastly, a 1912 article on the company noted that: “The present directors are Mr. C.G. Major, E.C. Stevens, Mr. P.H. Stevens, and P.C. Major. Since the death of Mr. Archibald Smith, the direct connection of the Smith family with the business has ceased.”[2] Somewhat surprisingly, no obituary of Archibald Smith has been found nor has it been possible to confirm when he died. His disappearance from the scene remains a mystery.

However, the strong foundation he built, an effort that began in 1859, allowed the company to continue to thrive in his absence; first under the leadership of Charles George Major and, after his death, of Edwin Charles Stevens. In the period between 1903 and 1910, the company continued to expand its business and eventually reached a point where it needed additional manufacturing capacity. It had previously built an earlier factory, the Janus Works, in Battersea in 1880. In 1910, plans were made to build a second factory:

“Owing to the rapid increase in their business as lift manufacturers, Messrs. Smith, Major and Stevens, Ltd., for some time past found their Battersea premises very inadequate for their growing needs, and have been to provide new works, which are now in course of erection at Northampton … A portion of the staff and a considerable number of workmen will be retained in London.”[21]

The Northampton plant was completed in December 1910, and the company began their long association with this area.

This brief history has, it is hoped, served to set the stage for the examination of the 1927 specification and tender. This examination will reveal the state-of-the-art VT business practices employed by Smith, Major & Stevens in the late 1920s; practices made possible by the individuals who built one of the great British lift manufacturing companies.

References

[1] Advertisement, Atchley’s Builders’ Price Book for 1869, Atchley & Co. (London: 1869).

[2] “Round the Shops,” The Engineering Review (15 April 1912).

[3] The Builder (2 December 1843).

[4] Andrew Smith, Miners’ Safety Cage or Car, British Patent No. 2149 (30 March 1855).

[5] Andrew Smith and James Thompson Mackenzie, Improvements in Ordinance and Small Arms, By Applying Thereto Projectile Force Obtained from High-Pressure Steam, British Patent No. 2695 (21 December 1854) (Not sealed).

[6] “Our Weekly Gossip,” The Mechanics Magazine (25 March 1859).

[7] “Police Intelligence (This Day): Marlborough Street,” The Sun (London) (23 June 1859).

[8] Archibald Smith, Improvements in Machinery for the Manufacture of Wire Rope and Other Ropes, British Patent No. 442 (11 August 1857).

[9] Advertisement for Archibald Smith, The English Mechanic (23 June 1865).

[10] “Obituary: John Sanders Stevens,” The Entomologists Monthly Magazine (September 1903).

[11] Archibald Smith & Co. Advertisement, Atchley’s Builders’ Price Book for 1869, Atchley & Co. (London: 1869).

[12] Archibald Smith & Co. Advertisement, The Building News (4 August 1876).

[13] Spon’s Engineer’s and Contractor’s Illustrated Book of Prices of Machines, Tools, Ironwork, and Contractors Material for 1876. (E. & F.N. Spon, London: Charing Cross, 1876).

[14] Building News and Engineering Journal (19 October 1877).

[15] John Sanders Stevens and Charles George Major, Hydraulic Lifts, British Patent No. 5721 (30 December 1881).

[16] “Stevens & Major’s “Reliance” Hydraulic Lift,” The Engineer (18 May 1888).

[17] Spon’s Engineer’s and Contractor’s Illustrated Book of Prices of Machines, Tools, Ironwork, and Contractors Material 1895-6. (E. & F.N. Spon, London: 1895).

[18] “Catalogues, Etc.,” The Electrician (8 May 1903).

[19] “Miscellanea,” The Engineer (31 July 1903).

[20] “Trade Notes,” The Building News (12 November 1909).

[21] “Trade Notes,” The Building News (15 July 1910).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.