“A Heritage of Unsuspected Richness”

Oct 5, 2023

Belgium’s historic lifts gain legal recognition.

by Jérôme Bertrand, Céline Chéron, Lauréline Tissot and Muriel Muret

photos © Homegrade

Like other European countries, Belgium — and Brussels in particular — has a stock of old lifts of remarkable historical value. They generally serve small buildings from the first half of the 20th century, the height of which rarely exceeds five or six floors. Carefully integrated into the interior decor of buildings and often placed in an open shaft in the center of the stairwell, they are the work of specialized craftsmen such as lift engineers, ironworkers, cabinetmakers and even master glassmakers.

Ensuring the safe use of these particular pieces of equipment while preserving their authenticity represents a major challenge. Since Belgium is a federal state that includes several levels of government, this issue falls to both the Federal Public Services of Economy and Employment, responsible for the safety of elevators, and the three regions (Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels), which are responsible for heritage protection.

As early as the 1980s, lifts — for both professional and public use — were transformed to comply with the requirements of the General Regulations for Work Protection (RGPT). Inspired by the European recommendation 95/216/EC of June 8, 1995, the Royal Decree of March 9, 2003, extended this compliance obligation to private lifts in residential buildings.

Citizen Mobilization for the Preservation of Old Lifts

Faced with the fear of having to make major alterations to their elevators, with the risk of altering the appearance of their building, groups of owners including the Comité contre la transformation obligatoire des ascenseurs (Committee Against the Compulsory Transformation of Elevators) and, more recently, the Save Our Elevators Association, formed and reacted energetically. They have played a key role alongside the traditional owners’ unions (the Syndicat National des Propriétaires et Copropriétaires (National Association of Owners and Co-owners) and the Verenigde Eigenaars (United Owners) to mobilize and raise awareness among political decision-makers. Their efforts have resulted in several amendments to the Royal Decree since 2003, and have put the issue on the agenda. The Government of the Brussels-Capital Region, on the initiative of its Secretary of State for Heritage Pascal Smet, thus freed up financial resources in 2020 to produce an inventory of lifts of historical value. To carry out this research, a partnership was formed between Urban.brussels, the administration in charge of cultural heritage, and Homegrade, a regional information center specializing in renovation advice for individuals.

Recent Developments in Elevator Safety Regulations

The Royal Decree of March 9, 2003, on elevator safety requires the compliance of all elevators without distinction, whether for public or private use. It imposes on elevator owners and managers a series of obligations including — in addition to periodic inspections — the carrying out of a risk analysis by an External Department for Technical Control (Service Externe de Contrôle technique – SECT) and the implementation of a modernization program. The risk assessment is based on a checklist that proposes a standard modernization solution inspired by international standards such as EN 81-80 for each safety aspect to be examined. Some of these solutions pose real problems for preserving the heritage of elevators and the buildings that house them, such as the obligation to secure open shafts with physical enclosures. In its initial version, the Royal Decree already allowed the possibility of considering the historical value of the lift by authorizing “alternative solutions.” However, these had to have “an equivalent level of security” to that of the standard solutions recommended in the risk assessment analysis. Without a clear definition of acceptable alternative retrofit solutions, SECTs were forced to stick to international standards.

Each elevator listed in the inventory is the subject of a richly illustrated note that describes its historical, aesthetic and technical value.

However, the latest modification of the Royal Decree, in force since January 1, 2023, marks a new step towards a compromise that opens the door to better consideration of the heritage value of elevators with historical value, while guaranteeing the safety of users and the professionals responsible for maintenance. Historic elevators are now the subject of a separate category — recognized by regional heritage services by means of a certificate — that describes the heritage characteristics to be preserved (open shaft, landing doors and grilles, old control and call buttons, for example). Heritage characteristics could also include old cabins and noteworthy machinery. To allow the study and implementation of alternative solutions with a level of safety deemed “sufficient” and no longer strictly “equivalent,” the deadline for the modernization of elevators with historic value has been extended to December 31, 2027.

Inventory of Historic Lifts in the Brussels-Capital Region

Designed to complement the inventory of architectural heritage, the inventory of lifts of historical value was carried out in a participatory manner. A vast communication campaign has been launched to call on owners to report their lifts and request certificates of historical value. As a result, in addition to the 20 or so lifts already listed in historical monuments, more than 350 lifts have been inventoried to date. Several hundred other installations with potential heritage value have also been identified and remain to be studied.

The year 1958 is a pivotal date from which new regulations on safety in Belgium radically modified the aesthetics of lifts by imposing shafts with continuous walls and solid landing doors.

Catalogued on a website, L’inventaire des ascenseurs historiques, the inventory of historic elevators in the Brussels-Capital Region is unique. It is geared toward both the general public and experts. Each elevator listed in the inventory is the subject of a richly illustrated note that describes its historical, aesthetic and technical value. A glossary allows amateurs to familiarize themselves with the vocabulary specific to old lifts.

The inventory focuses on elevators put into service before 1958 in residential buildings. The year 1958 is, indeed, a pivotal date from which new regulations on safety in Belgium radically modified the aesthetics of lifts by imposing shafts with continuous walls and solid landing doors.

Inventory work has also been undertaken in other regions with some very beautiful examples in large cities such as Ghent, Antwerp, Liège and Charleroi.

A Knowledge Tool

The systematic visits to buildings carried out for the realization of the inventory, supplemented by the analysis of the catalogues of manufacturers and the examination of the trade almanacs in the City of Brussels, make it possible to sketch the contours of a history of the lift in the Belgian and Brussels context. From the 1890s, the presence of elevators was mentioned in advertisements for major hotels and the first department stores. Apart from the lift of the Hôtel Métropole (1894), that of the Grands Magasins Old England (circa 1899) and that of the Gresham Insurance building (circa 1905), these first installations have left few material traces. The presence of hydraulic elevators is attested by archival documents, but the elevators listed in the inventory are all electric counterweight elevators.

The oldest elevators preserved in apartment buildings date back to the 1910s and are particularly elaborate and monumental. From the 1920s, the lift experienced a veritable golden age that coincided with the development of apartment buildings. Until World War II, the elevator was most often placed in an open shaft in the center of the staircase. It occupied a central place in the scenography of the common parts. Everything was done to provide the user with cozy and reassuring comfort: automatic call and control buttons, seats, mirrors and bevelled glass. Shaft railings, landing doors and the cabin could be supplied by the lift company and chosen from a catalogue, but in some luxury buildings, the architect was involved in the design of these elements. In any case, the use of specialized craftsmen is noticeable in every detail of the installation. In keeping with the development of modernism in architecture, a trend toward simplification of forms and standardization emerged in the 1930s. From that time, in more modest buildings, the elevator was often placed in a closed shaft to save space. This arrangement tended to become more common in the post-war period and became the norm from the end of the 1950s.

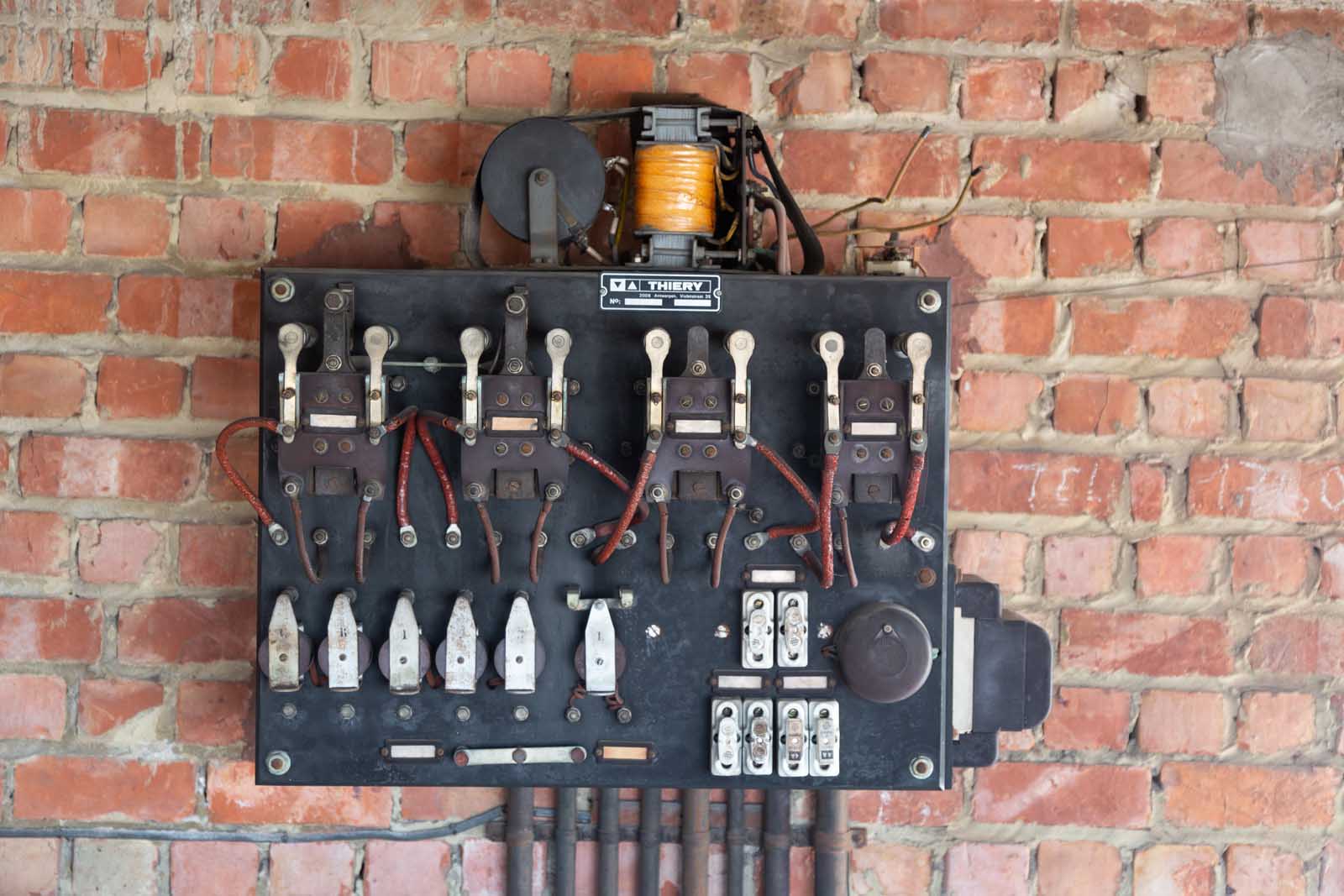

Brussels, a city in the heart of Europe, welcomed international brands from the end of the 19th century. From 1895, companies such as the U.S.-based Otis were often represented initially by local companies before setting up local branches. Before World War I, Hopmann (Germany), Waygood (England), Edoux and Abel Pifre (France) were active in Brussels. Stigler (Italy) arrived in 1920, Schindler in 1927, and Schlieren (Switzerland) and ASEA (Sweden) in the 1930s. Very early on, Belgium also had major lift brands such as Jaspar in Liège (present in Brussels from 1914), Strobbe in Ghent, and Thiery and Daelemans in Antwerp. In Brussels, a number of small builders or installers were active. These included ACMF, Excello, Mariën, Atlas and Thirionet. This diversity of brands, both internationally and in Belgium, disappeared from the 1960s onwards, following numerous mergers and acquisitions: Stigler was taken over by Otis in 1947, Schlieren by Schindler in 1960, Jaspar by Westinghouse in 1961 (of which the European elevator branch was taken over by KONE in 1974), Daelemans by what was then ThyssenKrupp in 1979…

Observations carried out in situ as part of the inventory make it possible to rediscover the history of large world firms, as well as of smaller companies and locally active craftsmen. In this respect, the still-authentic technical elements discovered in the field constitute precious witnesses. It is now possible to lay the foundations of a chrono-typology that enables identification of the original brands of elevators transformed over time, even if their name has disappeared or been replaced by that of another brand. Schindler, which dominated the Brussels market in the interwar period, also made a specialty of replacing existing lift machinery components. These old transformations are, in themselves, of heritage interest.

The oldest elevators preserved in apartment buildings date to the 1910s and are particularly elaborate and monumental.

The use of specialized craftsmen is noticeable in every detail of the installation.

Modernization Challenge

With a significant number of historic elevators now being inventoried and legally recognized, the challenge now is to establish acceptable modernization solutions and identify companies capable of implementing them with the right equipment. During the first months of 2023, the federal ministries responsible for security set up working groups. Bringing together representatives of the heritage administrations of the three regions and professionals (elevator manufacturers and SECT), their objective was to seek — for certain critical points — solutions making it possible to reconcile safety and heritage preservation. When they are validated, these solutions can be used as an alternative to those resulting from international standards. Electronic solutions are explicitly permitted in the new legislation. Their use will make it possible to avoid implementing physical protection that is unsuitable for the heritage or having to replace elements of an original installation. It is already possible to secure retractable car grilles (very common in Belgium) for lifts with a speed less than or equal to 0.63 m/s using electronic safety curtains, rather than replacing them with solid cabin doors. In the same vein, the installation of a variable frequency drive with an electronic board allows preservation and modernization of old winches, thus combining the robustness of the old-time machinery with the precision and flexibility of new technologies. As part of securing open shafts, which represents a major difficulty, various electronic or electromechanical solutions (contactors) have been tested. Detection tests using a laser are currently underway on a classified lift in Brussels. In the context of a residential building, the application of this equipment typically used for the protection of industrial machines yields very conclusive results. Implementation of these solutions requires adaptations that must be carried out by specialized personnel. Professionals capable of modernizing and maintaining this heritage — generally active within small and medium-sized enterprises — are, unfortunately, too few in number. Training the sector in interventions on historic lifts is, therefore, an essential issue. Some solutions also require calling, as originally done, on craftsmen trained in other trades, such as ironworkers, cabinetmakers or even master glassmakers.

Conclusion

In Belgium, changes in the regulations applicable to lifts resulting from the dialogue between the federal administration responsible for safety and the regional heritage services allow us to hope for better preservation of lifts of historical value during modernization.

The inventory work brought to light an industrial heritage of unsuspected richness that ties in with the international history of lifts and its Belgian specificities. This research should arouse companies’ interest in the development and implementation of appropriate and respectful modernization techniques.

Exchanges with enthusiasts of old lifts (such as Jan Dumno from Wiesbaden and Christian Tauss of the Aufzugmuseum in Vienna) and professionals (notably through the mediation of the European Federation for Elevator Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) have revealed comparable issues beyond local particular features.

The sharing of experiences and best practices on an international scale — both in terms of historical information and the search for security solutions — will be decisive for the safeguarding of this heritage. The call is launched!

Sharing Knowledge To Preserve Heritage

Paul Mariën (PM) is one of the best connoisseurs of old lifts in Belgium and a true living memory. He entered the profession at a very young age and made it his passion. Although he has now passed on his small business, this outspoken Brussels resident continues, at age 82, his crusade for the preservation of historic elevators and the defense of artisan work. His knowledge is an essential reference for developing the inventory carried out by Urban.Brussels and Homegrade (UB&H). He took the time to speak with us about a few topics that are close to his heart.

UB&H: How did you become an elevator operator?

PM: I was born into this profession. My father was a former lift worker at Jaspar. He founded Ateliers Marïen in Brussels in 1938, then was mobilized by the military. Eventually, the company grew after the war. I was 17 years and 11 months old when my father died on Saturday, April 4, 1959, and on Monday, April 6, I was in the workshop taking care of business.

I continued my father’s business out of obligation because there were quite a few workers who had to be paid every week, but also because I liked it.

My training as an elevator operator was in the field, from the time I was a child. I was always in the workshop, even during holidays, or I accompanied my father with his workers to jobsites. I was always listening and gave my opinion. I went to school, but I couldn’t finish my last year due to my father’s death. Also, I liked being in the workshop very much. I didn’t like school so much.

I lacked training as an electrical mechanic, but I had books and my father explained things to me well. I learned on my own. I also had my father’s friends around me. These were engineers and workers who helped me and taught me a lot after his death. I was well taken care of.

UB&H: What do you like about this job?

PM: Each elevator is a challenge — finding solutions to keep it in service and systems to better secure it. My task is to respect the building as it was built and find easy and practical technical solutions. You don’t have to work in a building to mutilate it. It’s a lack of respect for the owners who pay you, and also for the past. Whoever lacks respect for the past, I doubt his future. I am not against modernity. Modern electronic solutions must be applied to old elevators to better protect them. You must always be on the lookout for new things. You must educate yourself all the time to keep up with the times. In the past, I did everything myself. Then, I took on subcontractors, which is better because they are specialized. For electronics, I surrounded myself with specialists. I’m not afraid to ask for information. I learned a lot from them because electronics is their daily life. My daily life, on the other hand, is the whole, like a conductor. When you are alone in your hopper, you are the master. This is your job, your domain. An architect hardly dared stick his head in the hopper — maybe less now than before. All that changed with prefabrication. Before, you had to do everything yourself. In my father’s workshop, there was even a forge. The business changed a lot in the early 1960s with the arrival of Italian products, which were less expensive than Belgian products but were of good quality. The material must be chosen taking into account the use of the elevator and traffic. You cannot compare an office building to a residential building, nor a building with one or four apartments per floor. But it’s not just the material. Execution is also important and must be perfect. Good material with bad performers results in disaster. With good material and good execution, the result is satisfaction.

UB&H: When did you begin your fight for old elevators and the profession of elevator craftsmen?

PM: In 1984, the “General Regulations on Protection at Work” (RGPT) were revised in regard to lifts used in the context of work. I started asking myself questions. I agreed for more security, but not just any security. Why was it necessary to secure the open shafts ducts, to close them? These shafts are the testimony of an era. The workforce was different. There were many highly skilled ironworkers. But, there are now fewer and fewer of them. Manufacturing is automated. Electricity supply was once not very reliable, and power outages were frequent. We were, therefore, very happy during the breakdowns to not be locked in a sardine box.

The modification of the RGPT for more security was linked to a desirable evolution, but it involved changing everything in the elevator, which was mainly going to benefit the builders. However, I found that solutions had to be found to make the lift more secure and improve it without demolishing it. It was at this time that I discovered the first electronic safety curtains at a trade fair in Paris. I then decided to apply them for a 1929 Stigler that I was taking care of in Ixelles, rue Forestière.

I am not against standards, but they must be applied with discernment. We must first improve security based on what exists, which is not currently the case.

You also have to think about products’ durability. Formerly, the material lasted 80 to 100 years. It is not like that today. Owners go into debt to pay for their apartment for 25 years and cannot change their elevator every 25 years to bring it up to current standards. Builders and banks gain, but owners suffer.

I defend the profession of the lift operator as a craftsman. You should not think first of the turnover, but of the customer and the proper execution of the work. Be proud of your work. We automatically have orders without having to run after them. A salesperson seeks to have orders; a craftsman looks for solutions, but it takes time. They are two different professions. Craftsmen are more exciting for me.

UB&H: How can we still train lift craftsmen?

PM: I did it with two young people, brothers who took over my family firm. We must make young people understand that their job is their freedom. I wanted to arouse their interest in this profession right from school. So, I went to a vocational school attended by students with an immigrant background, because I think they need to be offered prospects for the future. With the manual trades it is possible — provided these apprentices are given the time to get involved — to take responsibility.

I attracted about 10 students for this lift technician training. Some continued. There is one at Technilift and another at KONE, not to mention Aldair and Carlos Dos Santos, the ones who took over my workshop. It is essential to train young people on the ground. It takes six years to figure it all out, Aldair told me. The material to become an elevator craftsman is vast. In a big business, we have tables and procedures. It’s always the same thing. And when there are too many breakdowns, we replace the elevator. But the cause of the failure has not been found. On the contrary, a craftsman will look for the cause of the breakdown in order to remedy it.

References

[1] Becuwe, F., “Het Appel van de Historische Lift,” Monumenten en Landschappen, No. 4, 2023, pages 23-39.

[2] Becuwe, F.; Dawance, A.C.; Kivit, M.; and Muret, M., ” La modernisation des ascenseurs anciens, un défi patrimonial ” Thema & Collecta, No. 8, Brussels: ICOMOS Wallonie-Bruxelles, 2022, pages 176-183.

[3] Bertrand, J. and Chéron, C, “Ascenseurs d’hier, patrimoine d’aujourd’hui : les défis de la modernisation” Bruxelles Patrimoines, No. 13, 2014, pages 92-101. On line version : https://patrimoine.brussels/liens/publications-numeriques/versions-pdf/articles-de-la-revue-bruxelles-patrimoines/numero-13/article-13-9

[4] Deckers, G., “Liften, een levend technisch patrimonium,” Monumenten & Landschappen, No. 4, 1990, pages 3-16.

[5] Mouzelard, C., ” Rencontres à tous les étages, les ascenseurs historiques dans le quartier Brugmann-Lepoutre ” Les Nouvelles du Patrimoine, No. 168, 2021, pages 37-40.

[6] Royal Decree of March 9, 2003, relating to elevator safety, ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=fr&la=F&table_name=loi&cn=2003030952

[8] Inventory of Historic Elevators, elevators.heritage.brussels

[9] homegrade.brussels

[10] urban.brussels/fr

[11] saveourelevators.com

[12] aufzugmuseum.at

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.