Your authors examine the Kenya and U.S. VT landscapes, and make the case for a uniform global standard.

by John Antona and Shem Oirere, EW Correspondent

In spite of there being few elevator accidents reported in Kenya, the country could be on the verge of gazetting new country-specific safety standards on the installation, operation, inspection, testing, maintenance and repair of vertical-transportation (VT) equipment. The lifts and escalators technical committee at the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), a statutory body established in 1974 to provide and enforce guidelines on quality of products and services in the country, has developed a standard based on EN 81. Committee Chairman Ian Blackman told ELEVATOR WORLD that, under his leadership, the group managed to get EN 81 adopted into KEBS. The Kenyan standard is KS 2169. Despite the achievement of introducing a Kenyan standard, however, it has not been gazetted, and is therefore unenforceable, he said.

According to Blackman, enforcement of the standard is not the biggest worry for VT players in Kenya. He stated:

“Even if the standard does become a statutory standard, enforcement will be a major challenge for KEBS and other authorities. For example, how would a nonexpert confirm that a lift is compliant with every aspect of KS2169, either at the port of entry or during/after the equipment has been installed?”

Blackman has an MSc in Lift Engineering, is a member of the Fellow Society of Operations Engineers, and is managing director of Nairobi- based Elevator Concepts Ltd. (p. ???). He observed that East Africa is unlike Europe, where designs, especially of safety-critical components, are verified by testing laboratories, and manufacturers are issued test certificates. It is unlikely there are any such facilities in East Africa. Even if there were, these processes add costs to equipment, and, unless enforcement is strict, people are likely to continue to purchase cheaper, noncompliant equipment, he said.

At this time, Kenya and the rest of East Africa do not have standards specifically applicable to the design, construction, installation, operation, inspection, testing, maintenance, alteration or repair of lifts and escalators. Kenya’s Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) 2007 requires that passenger lifts be inspected by a government-approved inspector at least twice a year. The current process assigns responsibility to the lift owner/manager to hire an elevator company to perform the inspections. The owner then submits certificates of inspection to the Ministry of Labor as provided by OSHA.

With Kenya’s booming construction industry, estimated to have expanded by 8.7% in 2017, many commercial and residential buildings have been built in the country’s major urban areas. According to a local contractor, increased demand for VT equipment has made it difficult to verify sources of installed equipment, making it hard to authenticate.

It is common to see projects with lifts imported from manufacturers in China and North Africa that do not appear to comply with any recognized standards. In some cases, secondhand lifts from overseas are recycled. Sometimes, lifts are being installed by general tradesmen and put into service without any proper testing and commissioning, creating a potentially hazardous situation.

Across East Africa, there is no formal certification of lift technicians, raising the risk of unsafe and faulty workmanship. However, lift installers or maintenance companies have come up with their own internal training and procedures in an effort to ensure the safety of the riding public.

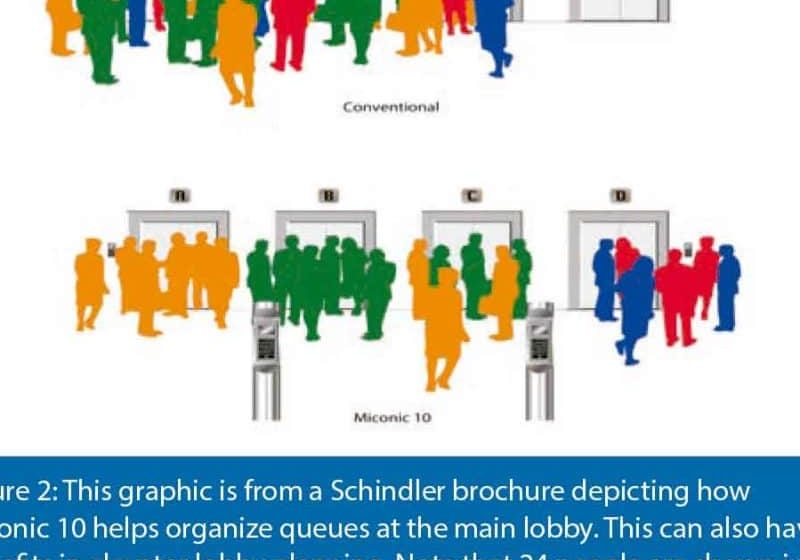

The market is currently dominated by international OEMs such as Otis, KONE and Schindler, alongside a large number of smaller companies that import and install equipment from a variety of sources in China, Europe, India and North Africa. As of June 2017 in Kenya, an estimated 36 lift companies were licensed by the Energy Regulatory Commission as registered electrical contractors. Apart from Blackman’s ECL, other market players include East African Elevator Co., Kenya Lift, Fuji Kenya Elevators, Aje Elevator Engineering and Ultra Electric Ltd.

In Kenya, building owners and elevator companies are delegated the responsibility for proper operation of elevators and the resulting safety of the riding public. The objective is the same in the U.S. What’s interesting is that different parts of the world have such divergent means of performing similar tasks. The scenarios in Kenya and the U.S. illustrate this well.

In the U.S., in part because of the high risk of litigation resulting from malfunctioning elevators, the elevator industry is highly regulated by codes and standards, as well as certifications, to ensure equipment and installers meet the minimum safety criteria required by approved organizations. In Kenya, the cost of regulating elevators through government entities would be prohibitive due to lack of local technical knowledge, training and structure. Additionally, the imposition of additional fees on building owners would be excessive.

The elevator industry is changing. Elevators are now being manufactured, installed and serviced all over the world with continuously changing new technology in constantly evolving, diverse environments. There are countries like Kenya with little or no government oversight on the one side, and, on the other, countries like the U.S. with intense oversight and regulations. Yet, the common objective is to provide safe and convenient VT for the public.

It may be time to have a leading international elevator standard as a minimum guideline for all. In our opinion, it is too expensive and inefficient to have elevator standards regulated by jurisdictional authorities in every city, county or state and to inspect and certify installations of equipment being manufactured by different companies around the world.

An international elevator standard should be written for manufacturers and installation and service companies. Such a standard should include proper training, certification and annual continuing-education requirements for elevator technicians. The owner of the building would be responsible for providing the local AHJ an annual inspection certificate by an accredited elevator company to receive an annual certificate of operation. The local AHJ would be responsible for verifying the certificate of operation is current and have the authority to issue fines or place an elevator out of service.

At minimum, an international elevator standard should include:

- Manufacturers having proper documentation that the equipment or any component has a certificate of compliance issued by an accredited elevator/escalator certifying organization. Each component or assembly should be identified by a label with the certificate number and date.

- Elevator company installers having proper documentation showing the elevator mechanics and helpers have been certified and, when performing inspections, have completed the annual continuing-education requirements of an accredited elevator inspection certifying organization. Each unit should identify the company registration number and date of installation by a label on the main controller.

It is time for U.S. standards ASME A17.1 and related codes, European standards EN 81 and related codes, plus any other standards out there to get together and establish common criteria leading to an international elevator standard. This would ensure the safety of the riding public, keep the cost of regulation and enforcement under control and allow global participation. Such a standard would greatly help many countries, like Kenya, that do not have an established organization overseeing its local elevator- industry needs.

A new world order might consider elevator systems a vital building component just like electrical, mechanical, plumbing, fire and structural systems. To include elevators under the purview of an entity such as a fire department would facilitate better coordination during plan reviews, inspections, issuance of the final certificate of occupancy and annual certification. Let the elevator companies be fully qualified and responsible for their trade, just like all other building trades.

How This Article Came About

by John Antona

In June, when planning my trip to Nairobi on my way to Tanzania, I contacted Shem Oirere, EW correspondent for Africa. I asked for advice on places to stay and, maybe, even plan a time to talk elevators. I used to visit Nairobi regularly when living in the Horn of Africa but figured that, since the 1980s, progress and development made my experience and qualifications as a Nairobi expert null and void. All my hesitations disappeared the moment I met Oirere. We became instant old friends and had a wonderful time together (Last Glance, EW, October 2018). We even indulged in a discussion about the elevator industry in Kenya. We decided it would be best to contact local industry professionals and collect the necessary information to write a paper describing — in general terms — the current process in Kenya. Additionally, we could highlight some differences, as well as similarities, between Kenyan and North American elevator standards. Oirere volunteered to take some time off from his busy schedule to contact local individuals and collect information. His notes are concise and very clear. They, along with my views from a different perspective, resulted in this article.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.