Why they are not ideal and an alternative method

Where is a great journalist called Lucy Kellaway, once the irreverent management columnist at the Financial Times, now full-time teacher and part-time journalist, who once wrote:

“But never have I learnt anything about myself as a result [of an Appraisal]. I have never set any target that I subsequently hit. Instead, I always feel as if I am playing a particularly dismal game of charades, with three disadvantages over the traditional parlour game. There is no dressing-up box; there is no correct answer to guess, and it isn’t remotely fun. The norm is a harrowing hour’s conversation during which you are forced to swallow an indigestible mix of praise and criticism referring to long-ago events, which leaves you demotivated and confused on the most basic question: Am I doing a good job? The resulting form is then put on file, making you feel vaguely paranoid, even though you know from experience how much attention will be subsequently paid to it: none whatsoever.”

Another fella you may have heard of is Douglas McGregor, who was a student of Abraham Maslow who developed the famous Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — McGregor being best known for his Theory X and Theory Y of motivation and management. So, these guys knew a thing or two about this people, performance and appraisal stuff. They contributed much to the development of management and motivation theory, and as far back as 1957, McGregor voiced doubts about appraisal systems in a Harvard Business Review article: He was sceptical. He argued appraisals have three basic aims:

- To provide information so that better decisions could be made about people — salary, promotion, transfer

- To let employees know how they were doing and what to do differently

- To provide a means of coaching and development

That obviously all seems pretty sensible; surely these aims make sense. You need to be able to make better decisions about people with better data, people need clear feedback, and it’s a great idea to help people find their strengths and develop them. So why do we want to sack appraisal systems?

Indulge me for a moment with a small thought experiment. Take a random selection of appraisees and appraisers (it’s horrible and alienating language to start with!) and ask them whether or not they enjoy or, indeed, get anything from the appraisal regime?

What do you think the answer would be?

Most staff believe that appraisals are done “to them” rather than “with them.

Why Do Appraisal Systems Fail?

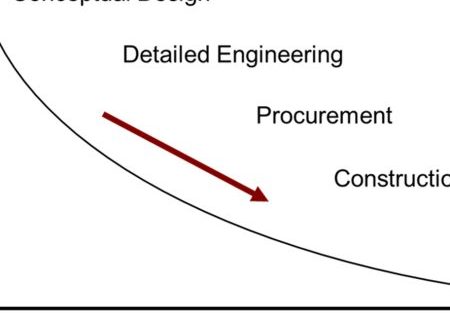

There are a number of reasons appraisal systems don’t work. We would take the Deming point of view and argue that the number one influence on the performance of an individual arises from “the system.” Let’s explore this and a few other issues.

- The system. There is a great experiment that you can find on YouTube, and that we sometimes replicate in training, called the red beads experiment. There are 4,000 beads in a box, 800 of which (20%) are red. The remainder are white, and the objective is to “manufacture” only white beads. Manufacturing is done by inserting a paddle with 50 depressions and the idea is to retrieve “only” white beads. The manufacturing operatives are then “trained,” and their performance appraised. The objective of the experiment is to show how variable a stable system can be and to show that individuals often have very little control over their performance!

- There is a Statius briefing paper detailing this in more detail available separately: “It’s a lottery — Are you the lucky one?” (If you are interested, email me, and I’ll send you a copy: [email protected])

- Training. Managers are rarely properly trained. There are various aspects of the appraisal system that require training: how to use the system, how to set objectives, how to specify success criteria, how to have a discussion so that there is a proper conversation without hidden agendas and bias.

- Bias. We all have bias, both unconscious and conscious, and this is extremely difficult to recognise and compensate for.

- Managers are rarely judged on their success with staff development. Whilst many would claim to believe that staff are their most precious asset, it is incredibly rare to find managers actually being rewarded for coaching, training and developing and growing their people.

- Power and balance. Most staff believe that appraisals are done “to them” rather than “with them.” The power lies with the manager. This is particularly true when scoring systems are applied to the appraisal process.

- Time lag. Appraisals typically occur annually, at best quarterly, so they are usually a discussion of events long forgotten and regurgitated simply for the pleasure of the appraisal.

- The impact. Time and effort are spent by both the appraisee and the appraiser thinking about performance and filling in forms, but in most instances, this information is rarely regularly used to create any meaningful change or impact.

- Salary. The appraisal review is often confused with the potential to obtain an increase in pay. As a result, the conversation often moves away from performance and gets hijacked by discussion about pay raises.

These are just a few of our thoughts on why appraisals should be sacked. But that in itself is not helpful, we need an alternative.

So, What’s the Alternative?

In order to explain the alternative, we’ll work through the process of recruiting someone for a new position. This approach will take us through various stages of the alternative.

The bedrock would be two documents:

- The Job Scorecard, or what we prefer to call a Success Profile.

- The Learning Log

A job description usually describes the activities or tasks that need to be undertaken to successfully execute the role. So alike but different from a job description, the Job Scorecard or Success Profile would set out the outcomes required from the job in hand.

The Learning Log is a separate document that sets out the activities that need to be learnt and mastered by the new staff member, probably over a period of six months to a year. This would include things that need to be mastered in the first week, the first month, the first quarter and then sensible chunks of time thereafter.

Having these documents fully developed and on hand before recruitment allows them to be used during the process to show how you will support people during their induction.

During the recruitment process you would then need to seek to understand things like:

- The individual’s learning style

- The individual’s preferred team role

This information can be teased out at interview, and with the use of various psychometric tests.

Once in post there needs to be regular, typically weekly, 15-30 min reviews of performance for the first three to six months.

In this world, a manager’s job is to guide, coach, direct and do whatever is necessary to assist their people to perform. In this world, the manager and their staff are held jointly accountable for the quality of work undertaken.

But critically, this is not a manager’s review of the new incumbent’s performance. This is a review by the new incumbent of their own performance against the Learning Log. So, this is “coaching,” not managing or appraising. The manager should hold the mirror for the new recruit. And given it’s coaching, “the thinking bubble” needs to be over the incumbent’s head, not the managers. The new recruit needs to drive the learning and development to improve their own performance. Questions that need to be asked as part of the weekly one-to-one include:

- What’s working well, and what have I learnt?

- What have been my challenges, and what have I learnt?

- What do I want to discuss during the 1:1 session?

- What could the company, or my manager, do better or differently?

The last question is important as it puts power back into the hands of the new recruit. It’s asking them to help you to help them. As a result of the review, the incumbent would agree with their manager’s actions and goals for the next period.

During this initial period, the Learning Log becomes the key reference document against which the new recruit would drive their own learning. Once the individual has been properly inducted, the weekly one-to-ones would be scaled back and then typically held monthly. At this point, the new recruit has been built up to fully understand the role, and the Success Profile would then be used to manage ongoing performance with the relevant key metrics being tracked and discussed monthly.

Throughout this process, feedback is essentially “immediate”; meaningful actions that have an impact are taken at the point required and eliminate the need for any annual review.

In this world, a manager’s job is to guide, coach, direct and do whatever is necessary to assist their people to perform. In this world, the manager and their staff are held jointly accountable for the quality of work undertaken. It’s a crazy world where people fail and get fired and managers get pay raises and promoted when it was their job to develop effective people.

Conclusion

Many companies spend thousands of hours implementing and executing appraisal processes. In one article, Kellaway calculated that Deloitte spent 2 million hours and £200m a year on appraisals! The time and effort involved in these processes is astronomical.

The alternative developed above moves the process from an annual, one-side-accountable, manager-administered/subordinate-received, performance appraisal to a two-sided, reciprocally accountable, individually driven, ongoing learning and development process.

As Kellaway suggests, the most basic question is “Am I doing a good job?” and this is much better answered (and corrected if required) by having your people control the conversation during a 15-min weekly chat.

I’ll leave the final word to Kellaway:

“Even for those whose managers did nothing to fill the gap, there would still be a net gain from scrapping appraisals. Time and energy would be saved, and the only two things lost would be cynicism and paranoia.”

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.