From marshmallow Peeps to Harley-Davidsons, PFlow Industries has been giving products a lift since 1977.

Make no mistake: vertical reciprocating conveyors (VRCs) are not elevators and do not transport people. Rather, they are carefully engineered systems for safely and economically raising and lowering materials in factories, warehouses, distribution centers, industrial plants or anywhere products and supplies need to be moved from one place to another. VRCs manufactured by Milwaukee, Wisconsin-based PFlow Industries — either hydraulic or mechanical depending on use — can be found in some interesting places, such as a mountaintop in Chile where a custom PFlow VRC facilitates continued access for maintenance for the world’s largest telescope, or at Harley-Davidson dealerships in Florida and Virginia, where VRCs are used to transport motorcycles between raised display areas and storage. At the Peeps & Co. retail store at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota, a D Series hydraulic VRC loads up to 1000 lb of apparel, accessories, gifts and, of course, the iconic marshmallow Peeps® treats. A series of mechanical VRCs help keep beer cold and crisp for National Football League fans at Hard Rock Stadium in Florida, home of the Miami Dolphins. “Our customer base is anybody looking to move materials vertically,” says PFlow National Sales Director Dan Hext. “It really doesn’t matter whether it’s boxes, pallets or dog food.”

Because VRCs do not transport people, that’s not to say they have nothing to do with the elevator industry; they do, in the sense that they can be part of larger vertical-transportation (VT) systems or can replace freight elevators in certain instances. Hext says:

“We have a lot of old buildings in this country that have freight elevators in them. The modernization process for those elevators can be very expensive and complex, so if the customer doesn’t need to move people, we can replace a freight elevator with a VRC. For this, we work through an elevator company because they had the original contract with the customer. It’s a natural relationship.”

At a Target store in Brooklyn, NY, a few years ago, a VT system installed by Nouveau Elevator (ELEVATOR WORLD, September 2021) was complemented by a Cartveyor® shopping-cart transport system engineered by PFlow. PFlow works with elevator companies “all the time,” Hext tells EW, including in challenging environments. “We have not met an environment that we can’t put things into,” Hext says. “We’ve done explosion-proof VRCs and ones on the coast where there is saltwater in the air that can penetrate the system.” PFlow VRCs are built to last, with the company installing its 20,000th VRC in 2023 and currently replacing units that were installed in the 1980s.

A Long and Accomplished History

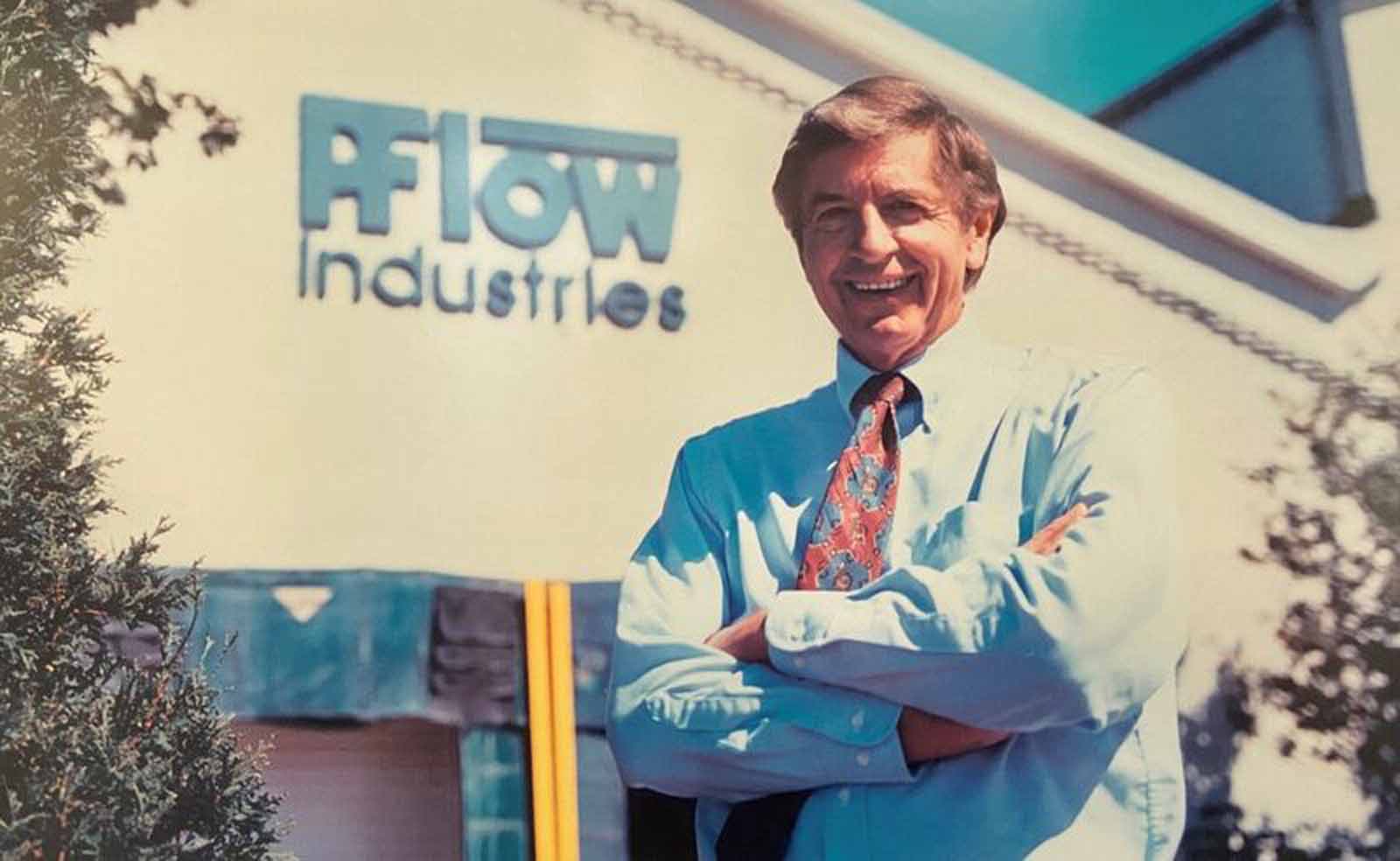

You might think PFlow is short for “product flow,” or start chuckling like a third grader about a potential other meaning. But the company’s name actually has the same first three letters as that of its founder, Bob Pfleger, who launched PFlow in 1977 after a 20-year career in the dock business. Pfleger, who passed away in 2002, faced a major hurtle with his nascent company, as elevator authorities in some states tried to legislate VRCs out of business. In a 2002 memorial about Pfleger, the Material Handling & Logistics® trade publication observed:

“[People in the elevator industry] claimed that a VRC was an elevator that didn’t meet elevator code. Truth was, you could replace your conked-out freight elevator with a VRC for less than it would cost to repair the elevator. When you scraped away all the they’re-not-safe rationale offered by the elevator people, you found the real reason: competition for business.”[1]

Known as the “Red Tag Gang” for the red tags elevator inspectors were wont to affix to VRCs, Pfleger and PFlow Vice President Herb Ruehl went state to state to fight elevator authorities in legislatures and courts to get VRCs defined as conveyors, rather than elevators. They succeeded. Fast forward 25 years, and VRCs had become an industry. Disagreements between the VRC industry and elevator authorities were “more often settled in the manufacturer’s distributorship rather than in the courtroom,” and the inspectors who had red tagged VRCs retired or passed away, resulting in “a kind of industrial truce.”[1]

Elevator Industry “Truce” Prevails

That truce prevails today, with Hext describing the relationship between the VRC and elevator industries as complementary, rather than adversarial. In the beginning, elevator industry opposition limited PFlow to production of inclined conveyors. Now, it primarily produces mechanical — rather than hydraulic — VRCs, he says. Its top seller is the M Series mechanical VRC designed for loads up to 10,000 lb that can be configured for any number of floor levels. The company says these versatile, two-post VRCs are ideal for high-speed and/or high-cycle automated systems. Hext says:

“It’s a very robust unit built for continuous duty. We overbuild everything we do, so they last practically forever. We have that reputation in the industry. If you’re looking to spend less money without the robustness and attention to detail, there are companies out there that do that. We just don’t get in that game. We build the best product out there that’s going to last the longest.”

We overbuild everything we do, so they last practically forever.

— PFlow National Sales Director Dan Hext

The company is currently seeing a lot of business from the data storage industry. The lion’s share of its clients is in the U.S., but PFlow works internationally, including on two current jobs in Israel (geographically distanced from areas of conflict). The company generally produces hundreds VRCs per year, including through working with elevator companies.

Code Development Counts

Dating back to when Pfleger first took a stand for VRCs in the 1970s, PFlow has remained very active and instrumental in code development. The company helped write ASME B20.1 code for conveyors and related equipment to ensure separation between VRCs and elevators. “To this day, we sit on the board,” Hext observes. “If there is any upcoming state or federal legislation that wants change in our industry, we’re on the forefront of it and can help guide it, with safety being the first consideration.” The company also employs a lobbyist to act as a legislative watchdog.

Growth in Size and Numbers

When Hext joined PFlow in 1999 (ironically, from a career as a police officer), the company was in a 100,000-ft2 facility. It has since nearly doubled, to 185,000 ft2. That is, in part, to accommodate the growing workload and employee numbers. Hext was PFlow’s 50th employee; today the company is at 173 on the payroll, including a team of more than 30 in its engineering department. Hext says this is probably more than double the number of engineers of “all our competitors combined,” and part of what sets PFlow apart. He says:

“Lots of people make products that move a pallet, and there are a handful of companies that do it very well. But, when you get into anything odd, our competition falls by the wayside. That’s because we can engineer things from a clean sheet of paper. Our customer service department is also second to none in the industry. They’re trained on the equipment and take calls on a daily basis to help customers install, maintain and service their equipment.”

PFlow is a unique player in a niche industry, and Hext says he thrives in an environment that presents new challenges and opportunities to help customers every week. “I’m a people person, and this really fits my personality,” says Hext, who never looked back from leaving law enforcement and is celebrating his Silver Anniversary with PFlow this year. While the company is well-armed with skilled engineers, it is always looking for expert welders. Going forward, Hext says there is no doubt PFlow will continue to hit new milestones and realize one-of-a-kind projects, including in partnership with the elevator industry.

Highlights of PFlow Industries’ History

- 1977 — Bob Pfleger reaches the end of an influential 20-year career in the dock business. Pfleger starts PFlow Industries in Milwaukee with an idea that created a new product called the inclined vertical conveyor.

- 1979 — A huge fire damages the majority of a PFlow plant in Columbus, Ohio. The structure of a PFlow Hy-Lift kept the wall from collapsing, saving the lives of four people.

- 1980 — Ted Ruehl joins PFlow. PFlow’s first international Hy-Lift is installed in Belgium.

- 1981 — PFlow replaces the inclined reciprocal conveyor with the VRC.

- 1983 — PFlow introduces the F Series, four-post VRC and expands the Hy-Lift product line to 12,000 lb and 15 ft X 15 ft.

- 1984 — PFlow starts full-scale manufacturing and moves into a 3,500-ft2 office and 13,000-ft2 plant in Milwaukee.

- 1987 — PFlow successfully changes the individual state codes of all 50 states, making VRCs available for installation throughout the country.

- 1989 — May goes down in history with 70 lifts sold in one month.

- 1990 — PFlow introduces a new paint system designed to cover every surface and literally “wrap around corners.”

- 1992 — The D Series hydraulic lift and the 21 Series hydraulic lift are introduced. Mark Webster and Ted Ruehl are promoted to vice presidents.

- 1994 — PFlow co-founder Herb Ruehl, who defined and classified VRCs for their use and not their look, retires. PFlow adds 2,600 ft2 of office space.

- 1997 — PFlow designs two windows that split like freight elevator doors for a home in Florida. At 33 ft wide X 22 ft high (17,000 lb each), the windows welcome in coastal breezes.

- 1999 — PFlow assists with a large modular automated parking system that was noted in the Wall Street Journal. PFlow transitions to an ESOP (employee stock ownership plan) business.

- 2001 — PFlow expands its manufacturing space by 38,000 ft2. PFlow designs a servo-hydraulic lift system capable of transporting an RV. Cartveyor is introduced — a shopping cart conveyor that can run parallel with a passenger escalator or as a standalone unit.

- 2002 — Bob Pfleger: March 7, 2002. A friend, mentor and innovator passes away, but a legend never dies. Ted Ruehl is appointed president.

- 2003 — PFlow purchases its current facility, which includes 125,000 ft2 of office and manufacturing space.

- 2006 — PFlow acquires Langley Manufacturing, a longtime lift competitor.

- 2008 — The PFlow F Series creates a passageway into Texas Memorial Stadium for the world’s largest bass drum, Big Bertha. PFlow volunteers mark 10 years of donating blood and helping save lives.

- 2009 — Carol Moore, a 1977 PFlow pioneer, retires. Moore frequented the company’s famous newsletter, “PFlow PFacts,” with her “Secretary’s Note.”

- 2013 — PFlow designs a very large four-post lift to clean the lens of the world’s largest telescope, known as LSST or the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile.

- 2014 — PFlow acquires a neighboring 26,000-ft2 building for expansion.

- 2016 — 17,000 PFlow Lifts are sold worldwide.

- 2017 — PFlow celebrates 40 years of service. The Quantum Drive MQ is introduced. Designed for PFlow’s mechanical two-post lifts, the MQ reduces vibration and enhances safety.

- 2018 — VP of Marketing and Cartveyor Sales David Dux retires after 34 years. VP of Sales Dan Walters retires after 31 years.

- 2019 — Pat Koppa joins PFlow Industries as president.

- 2020 — CEO Ted Ruehl retires after 40 years. PFlow Industries becomes a 100% employee-owned company.

- 2021 — Ted Ruehl is named chairman of the Board.

Reference

[1] Knill, Bernie. “Bob Has the Last Word,” MH&L, May 1, 2002.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.