City of Miami Beach: Representation of an Authority Having Jurisdiction

Mar 1, 2011

An illustration of “Authority Having Jurisdiction” in the City of Miami Beach, including: state’s delegation of authority, organization charts, inspection reports and forms, responsibilities of private and city inspectors, and the local ordinance process.

by John Antona

Chief, Elevator Safety Section, Miami Beach, Florida, USA

This paper was presented at Lucerne 2010, the International Congress on Vertical Transportation Technologies and first published in IAEE book Elevator Technology 18, edited by A. Lustig. It is a reprint with permission from the International Association of Elevator Engineers (website: www.elevcon.com). This paper is an exact reprintand has not been edited by ELEVATOR WORLD.

Key Words: Elevators, jurisdiction, violation, safety, contracted, inspector

Abstract

The City of Miami Beach is one of five jurisdictions delegated by the State of Florida to administer and enforce regulations governing the design, construction, installation, alteration, inspection and testing

of more than 2,000 City elevators. Utilizing standardized forms and reports, and demonstrating manpower flexibility with an inspection program that employs both private and City inspectors, costs have been controlled and program efficiency has been strengthened. This paper illustrates the structure of an “Authority Having Jurisdiction”, including: State’s delegation of authority, organization charts, inspection reports and forms, responsibilities of private and City inspectors, and the local ordinance process.

1. INTRODUCTION

The City of Miami Beach (CMB) was incorporated on March 26, 1915. It is currently governed by a city commission, composed of a publicly-elected mayor and six commissioners, who together serve as the policy-making body of the City. The City Manager ensures that policies, directives, resolutions and ordinances adopted by the City Commission are enforced and implemented.

Miami Beach is a small, “big city,” beach town with a variety of residents. A 24-hour, 7 day-a-week restless population of citizens and tourists mingle with the easy-going, slow-paced retirement community – often, they co-exist in the same neighborhood. The CMB is actually situated on a 7.1-square mile island located directly to the east of the City of Miami, and it is connected to the mainland by four main bridges. There are 93,721 permanent residents, with at least an equal number of visitors. Within the CMB limits, there are 9,000 residential units per square mile, 2 million square feet of office space, 16,000 hotel rooms and 3,400 businesses – a U.S. density second only to the

island of Manhattan, New York City. Vertical transportation is a critical element of the infrastructure because the CMB must serve such a large and diverse population.

The CMB was designated as an Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ) in 1990, pursuant to Chapter 399, Florida State Statutes, after signing an Interagency Agreement with the State of Florida, Department of Business and Professional Regulations (DBPR), Division of Hotels and Restaurants. Under this Authority, the CMB can administer and enforce regulations governing the design, construction, installation, alteration, inspection and testing of elevators. Other Florida jurisdictions enjoying the same privilege are the City of Miami, Reedy Creek Improvement District (the environs of Disney World), Miami-Dade County, and Broward County (Fort Lauderdale area). The Bureau of Elevator Safety (BES), within DBPR, monitors the State’s Contracted Jurisdictions (CJ) for compliance and is the AHJ for remaining territories in the State of Florida.

The CMB disengaged from Miami-Dade County and opened an independent Elevator Safety Section (ESS) as a component of the City’s Building Department for several reasons.

- To improve the process leading to issuance of Certificates of Occupancy by providing local coordination between different building trades during plan reviews and inspection processes, thereby facilitating timely completion of projects.

- To improve the safety of the riding public by managing elevator inspections and witnessing of tests, and by enforcing compliance at the City level.

- To improve communication and provide better service to constituents by following up on complaints and other issues that require intervention.

The ESS is managed by a Chief Elevator Inspector. He is assisted by two Senior Elevator Inspectors who perform compliance and permitted inspections, and by one Permit Clerk. They are complemented by administrative support personnel within the Building Department. Additionally, three Contracted Inspection Companies (CICos) assist the ESS with periodic inspections and tests of existing elevators; the CICos report directly to the Chief Inspector. Comprehensive roles of the ESS and CICos are detailed under Section 2, Organization.

Assigned responsibilities of the ESS and CICos include the periodic inspection and witnessing of tests, with related compliance inspections, of more than 2,000 elevator units. In combination, these inspections result in consistent enforcement of units with pending violations. Additionally, acceptance inspections and annual tests are conducted on approximately 60 units, in concert with more than 400 permits for alterations and repairs.

2. ORGANIZATION

“Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

– Antoine de Saint-Exupery.

2.1. Delegation of Statutory Authority

The Elevator Safety Act (2009) delegates Authority to the CMB to enforce applicable provisions of the Florida Building Code:

Chapter 399.13 – Delegation of Authority to Municipalities or Counties

(1) The department may enter into contracts with municipalities or counties under which the municipalities or counties will issue construction permits and certificates of operation; will provide for inspection of elevators, including temporary operation inspections; and will enforce the applicable provisions of the Florida Building Code, as required by this chapter. The municipality or county may choose to require inspections be performed by

its own inspectors or by private certified elevator inspectors. The municipality or county may assess a reasonable fee for inspections performed by its inspectors. Each agreement shall include a provision that the municipality or county shall maintain for inspection by the department copies of all applications for permits issued, a copy of each inspection report issued, and proper records showing the number of certificates of operation issued; shall include a provision that each required inspection be conducted by a certified elevator inspector; and may include other provisions as the department deems necessary. The county shall enforce the Florida Building Code as it applies to this chapter and may impose fees and assess and collect fines as part of its enforcement activities. A county or municipality may not issue or take disciplinary action against a certificate of competency, an elevator inspector certification, an elevator technician certification, or an elevator company registration. However, the department may initiate disciplinary action against a registration or certification at the request of a county or municipality.

(2) The department may make inspections of elevators in the municipality or county for the purpose of determining that the provisions of this chapter are being met and may cancel the contract with any municipality or county that the department finds has failed to comply with the contract or this chapter. The amendments to chapter 399 by this act shall apply only to the installation, relocation, or alteration of an elevator for which a permit has been issued after October 1, 1990.

2.2 Florida State Structure

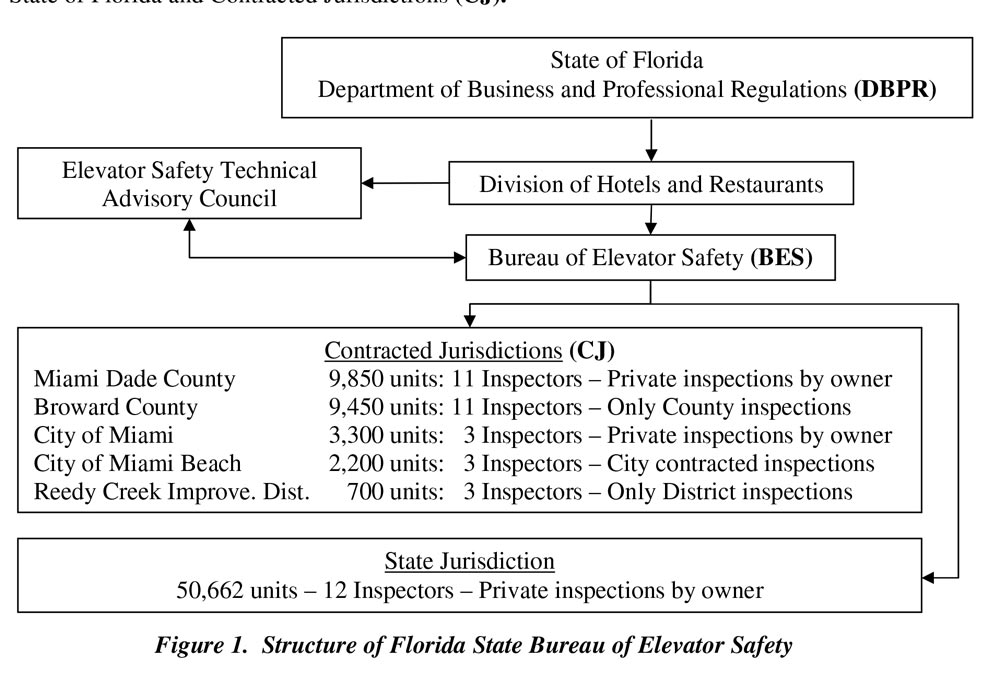

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the Bureau of Elevator Safety and its relationship to the State of Florida and Contracted Jurisdictions (CJ).

Figure 1. Structure of Florida State Bureau of Elevator Safety

The Florida State BES, Miami-Dade County, and the City of Miami require building owners to hire a private inspector to perform required periodic inspections and witnessing of tests. Private inspectors must submit a copy of their inspection report to the BES, or to the CJ and to the building owner, within five days after the date of inspection; failure to do so may result in suspension or revocation of the certification provided to the individual responsible for the inspection. Broward County relies solely on inspectors employed by the County; Reedy Creek Improvement District relies solely on inspectors employed by the District.

The CMB combines both inspection systems and has contracted three private inspection agencies to perform periodic inspections and tests. In addition, the CMB has two senior elevator inspectors performing compliance inspections, acceptance inspections, and tests for new elevators and existing units being modernized, or for repairs requiring a permit.

2.3 CMB Structure, Functions, and Processes

AHJ Regulatory Authority is, “the person or organization responsible for the administration and enforcement of the applicable legislation or regulation governing the design, construction, installation, operation, inspection, testing, maintenance, or alteration of equipment covered by this Code.” (ASME A17,1.-2005). Only those individuals who are Certified Elevator Inspectors with the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, holding the Qualified Elevator Inspector (QEI) credential, and who are registered with Florida State, DBPR, BES, are permitted to conduct elevator inspections within the CMB. The City’s Chief Elevator Inspector carries an Inspector Supervisor certification.

2.3.1 Re-Organization and Structure of the CMB ESS

A series of events about two years ago served as a catalyst for the current structure of the City’s ESS. The ESS found it increasingly difficult to schedule and perform periodic inspections and witnessing of tests due to increased regulatory requirements. The ESS asked City administrative officials to provide an additional inspector to supplement the ESS staff of four Inspectors and one Chief. During this period, one of the City inspectors resigned and a new Building Director assumed control of the Building Department.

The ESS was then faced with employing two inspectors during a hiring freeze. The new Building Director and ESS Chief brainstormed different scenarios, compared feasibility studies, and finally devised a practical, flexible and convenient solution: bid periodic inspections and witnessing tests to inspection companies capable of providing qualified inspectors on demand. The City would continue collecting fees from building owners and pay the inspection companies for services, on an as-needed basis. This proposal was approved by City administrators, a procurement bid was issued for inspection services, and three companies were selected to fulfill the contract. The City now authorizes certified inspectors to cover fluctuations in workload and eliminate bottlenecks, while controlling costs in periods of high and low demand.

2.3.2 Functions of the ESS

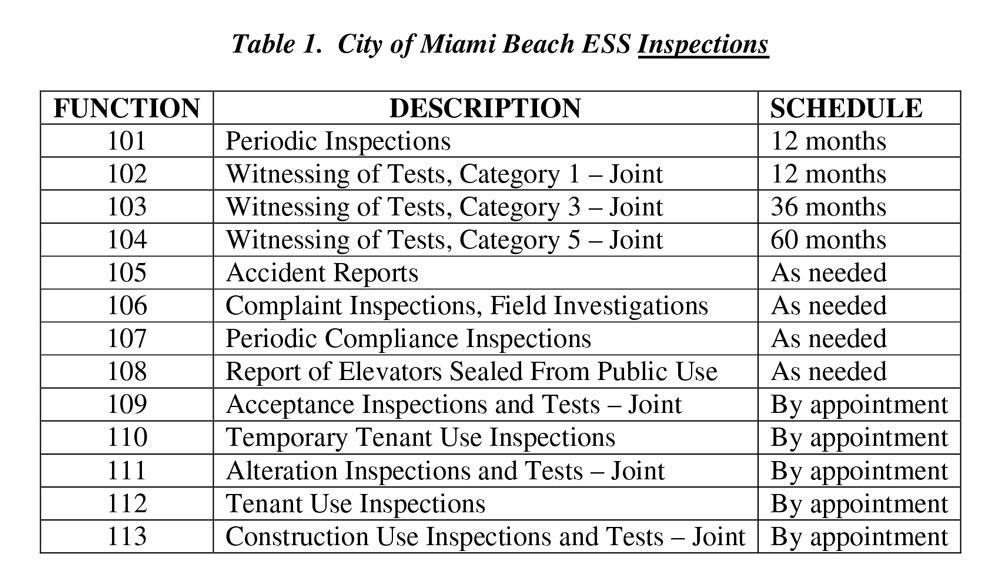

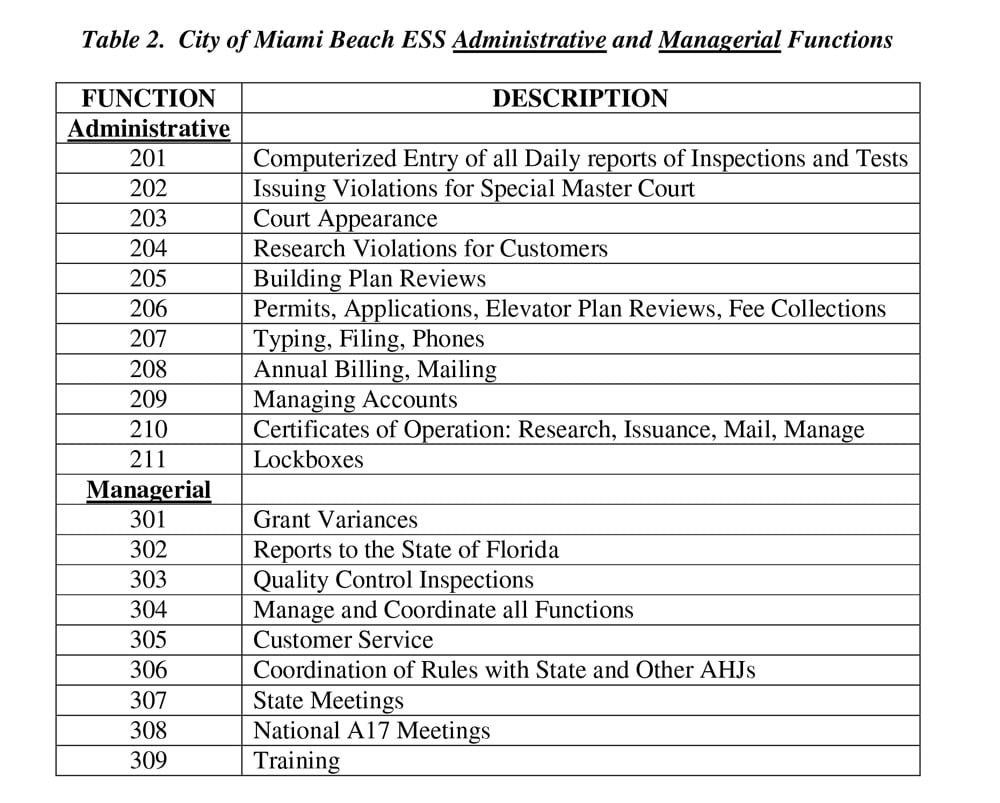

Basic functions of the ESS are divided into three categories: Inspections, Administrative and Managerial, described further in Table 1 and Table 2, below.

Table 1. City of Miami Beach ESS Inspections

Table 2. City of Miami Beach ESS Administrative and Managerial Functions

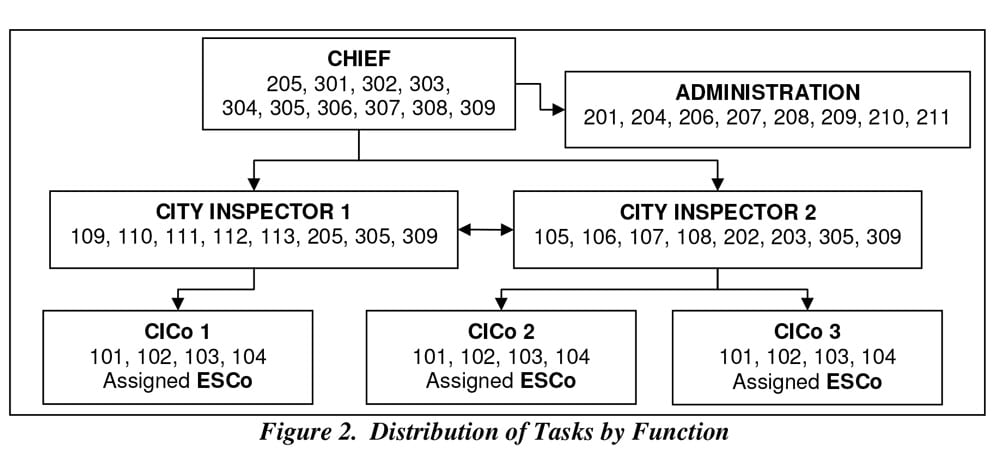

Figure 2, provides an overview of the Distribution of Tasks by Function for the ESS. CICos work with assigned Elevator Service Companies (ESCos) and they report to an ESS Inspector. The ESS Inspector verifies submitted reports of violations for accuracy before they are entered into the computer data system. Continued

Figure 2. Distribution of Tasks by Function

2.3.3 Processes of the ESS

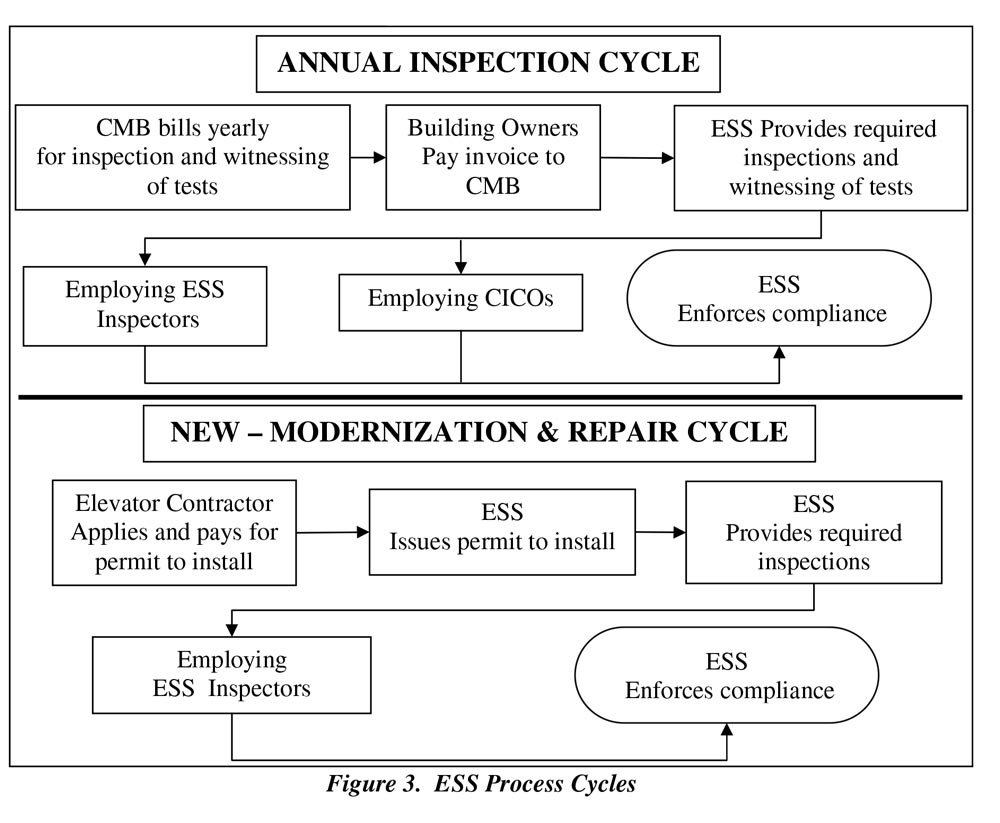

Figure 3, below, illustrates the ESS Annual Inspection Cycle. The CMB produces invoices and collects fees from building owners to support administrative costs and enforce compliance of existing units inspected by both the ESS and CICos. The New – Modernization and Repair Cycle requires elevator contractors to pay for permit applications to install equipment and for subsequent inspection by ESS Inspectors. Only ESS performs these inspections to ensure consistent and uniform requirements on new and altered units.

Figure 3. ESS Process Cycles

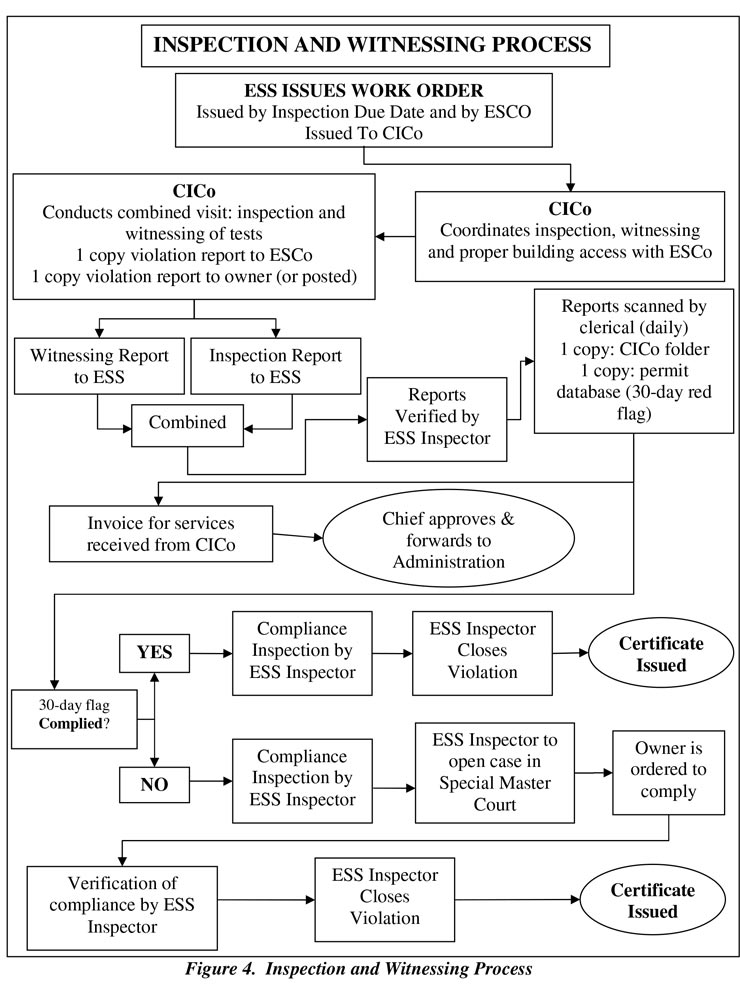

Figure 4 provides a description of the CMB Inspection and Witnessing Process. Illustrated are the steps involved by both CICo and ESS Inspectors to complete all functions by task, from the day the inspection request is generated to issuance of final Certificate of Operation.

Work Orders are issued to each CICo, divided by ESCo. The Work Orders, by due dates, identify units needing combined periodic inspections and annual tests, and separately, those units requiring periodic 5-year tests. CICos coordinate building access and witnessing of tests with the ESCo and provide a copy the violations report to the owner and a copy to the ESCo. The original report is submitted to the coordinating ESS Inspector and scanned into the ESS computer system. After 30 days, the report is flagged for compliance verification and sent to the ESS Inspector. If the elevator is found compliant, violations are closed and a Certificate of Operation is mailed to the owner. If found non-compliant, the report becomes a violation and a case is opened for the Special Master Court, where fines may be assessed. If fines are not paid, a lien may be placed on the property, and/or the elevator may be removed from service. When compliance is achieved, a Certificate of Operation is given to the owner.

Figure 4. Inspection and Witnessing Process

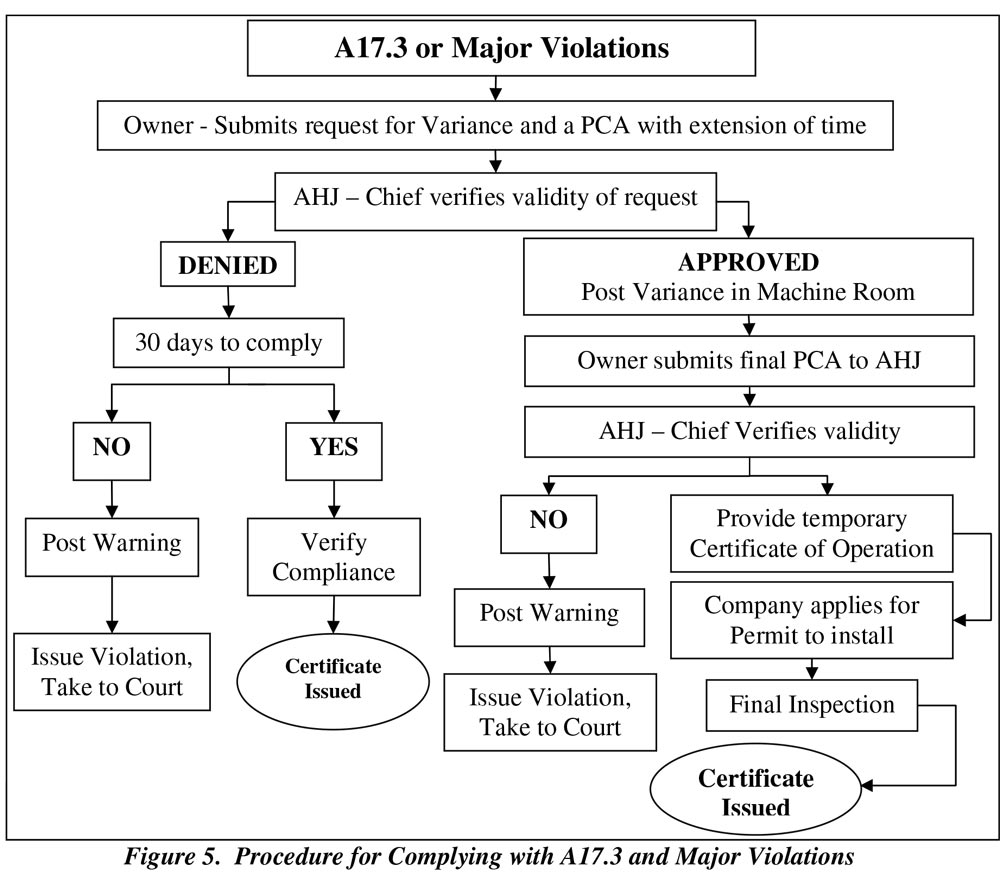

2.4 Retroactive Compliance

Another important aspect of an AHJ is retroactive compliance on existing installations, as required by ASME A17.3 and adopted by the State of Florida. Retroactive compliance can be expensive and place a heavy burden on the owner. The ESS has the authority to grant a variance on the installation, if the owner provides a Plan of Corrective Action (PCA) acceptable to the Chief Elevator Inspector. Figure 5 provides an illustration of the steps required to obtain compliance with major violations or retroactive ASME A17.3 violations. Continued

Figure 5. Procedure for Complying with A17.3 and Major Violations

After receiving an ASME A17.3 violation, a building owner must submit a Request for Variance, with an initial Plan of Corrective Action (PCA), to the ESS Chief. The request specifies time required to seek proposals for the work, to apply for and obtain funds for costs involved with the PCA, and for assigning contracts to an elevator and/or fire alarm company, and an electrical/mechanical contractor, if necessary. The ESS Chief verifies the validity of the PCA and grants a Variance, allowing for use of the elevator while compliance of A17.3 violations is in progress.

Within 90 days, the owner must submit a final PCA with a copy of all signed contracts. The elevator permit becomes the master permit for the project, while fire, electrical, mechanical are treated as sub-permits. When all inspections are completed and final inspection is passed, the elevator(s) is issued a Certificate of Operation. This process may take as long as five years for large projects involving several elevators. Coordination of each function between the ESS and the owner is essential to ensure that building tenants are properly informed and that the project is completed without exposing employees and the public to unsafe conditions.

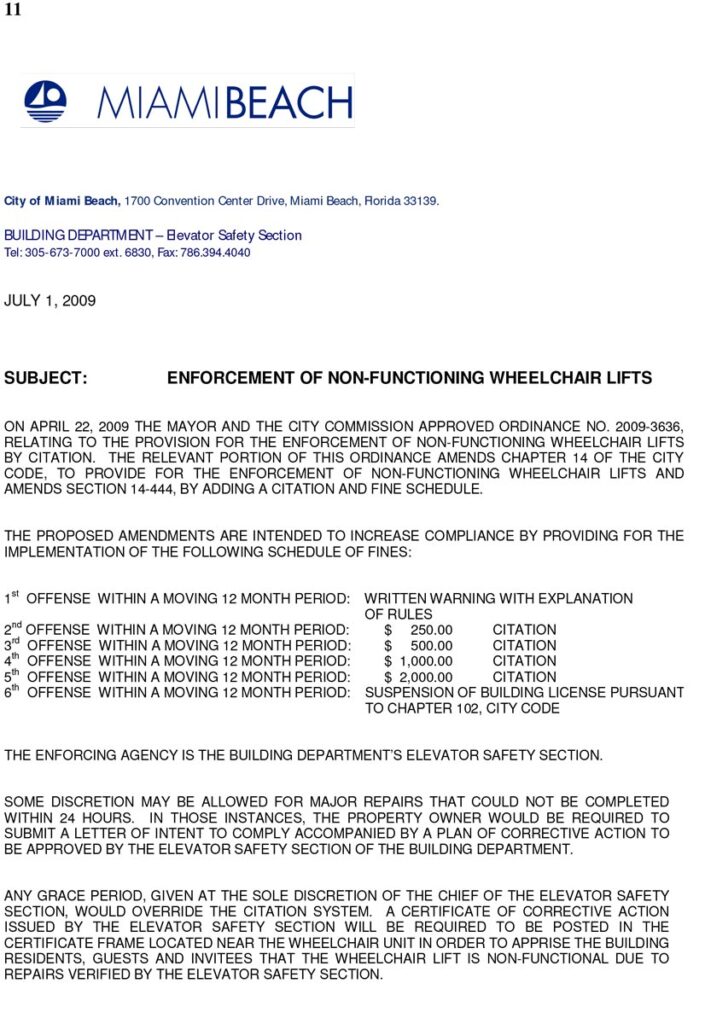

2.5 Local Ordinances

Local ordinances are also used to enforce compliance above and beyond regulations codified by the State of Florida or enumerated in National standards. They are applied in specific local situations requiring special attention. One such example is CMB Ordinance 2009-3636, issued in an ESS bulletin (“Appendix A”) after it was approved by the Mayor and City Commission. This Ordinance provides more stringent regulations on ADA Lifts in response to complaints received from visitors, and slow responses from building owners, to comply with ADA requirements through the standard violation process.

3. CONCLUSIONS

“Laws too gentle are seldom obeyed; too severe, seldom executed.” – Benjamin Franklin

The goal of any AHJ is to protect the safety and welfare of the riding public. This is done by ensuring that building owners abide with the letter of regulatory codes which serve as guiding processes to ensure safety and reliability. At a minimum, an AHJ must be capable of performing inspections and witnessing of tests at required intervals, maintain records of all violations issued, and, after a prescribed time, assure that building owners have complied with corrections of violations. It is only then, after these essential tasks have been accomplished, that an AHJ should authorize issuance of a Certificate of Operation.

The CMB has accomplished this critical mission by creating and achieving a full inspection cycle and by controlling compliance at the local level. With the incorporation of an independent Section within the CMB Building Department, ESS was molded on the desires and complexities of its constituents. Yet, the ESS has maintained its authority to enforce State statutes and industry rules and regulations designed for the safety of the riding public.

What truly distinguishes Miami Beach from other jurisdictions is the City’s innovative approach of using contracted inspectors to perform periodic inspections and tests. Contracted inspection companies can adjust the number of their inspectors according to fluctuating demands provided by ESS Work Orders. Delays can now be attributed to elevator companies providing insufficient manpower to comply with inspection schedules, rather than to failures of the ESS. Another distinctive feature of the CMB can be attributed to the exclusive assignment of compliance inspections and code enforcement requirements to CMB inspectors; consequently, these assignments are strictly controlled by the City jurisdictional authority.

With a more efficient distribution of administrative and managerial functions, ESS inspectors now provide valuable customer service to constituents – responding to complaints concerning vertical transportation questions, and offering, when necessary, clarification of violations issued by contracted inspectors. ESS Inspectors also have time to provide advice concerning best methods to comply with pending violations.

There are noticeable differences when a comparison is made between inspection and compliance processes of private elevator inspectors (as used in other jurisdictions), vis-à-vis City-employed and contracted inspectors, as used in the CMB. Private inspectors are hired by building owners or by an elevator company maintaining the project – employment that may lead to conflicts of interest. To comply with jurisdictional authorities, private inspectors may have to write an extensive report of inspection violations. To satisfy the authorities, building owners may be forced to spend large sums of money, soliciting a negative reaction toward the inspector. Similarly, writing violations that demonstrate poor service by an elevator company generates the company’s negative reaction toward the inspector. Consequently, private inspectors may feel reluctantly forced to relax their professional judgment and engage in bad business practices.

If a city has been delegated as an Authority Having Jurisdiction concerning elevators, all plan reviews for different trades, including elevators, will be coordinated at the local level when new buildings are designed.

On the other hand, if the Authority Having Jurisdiction for elevators is at a county or state level, there will be no coordination for plan reviews between elevators and the other building trades. This may result in a process that leads to costly errors and can delay completion of projects.

It is the author’s opinion, echoed by Benjamin Franklin’s thoughts, that code enforcement must be neither too severe nor too gentle. The use of unsafe and defective lifting devices creates a significant probability of serious and preventable injury, as well as exposes employees and the public to unsafe conditions, and municipalities to potential liability. Enforcement must accommodate the needs of local constituents, while assuring compliance with the critical AHJ goal of providing for the safety of life and limb. Including the ESS as a vital component of the CMB Building Department, and therefore as an extension of the CMB government, assures congruence with the City’s Mission Statement, “We are committed to providing excellent public service and safety to all who live, work, and play in our vibrant, tropical, historic community”.

4. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author acknowledges Alex Rey, Building Department Director, City of Miami Beach, for providing valuable information in the preparation of this paper. Special acknowledgement is also extended to Kathleen Antona for assistance in editing and formatting this paper.

6. REFERENCES

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (2005). Part 1: General, In: Addenda to ASME A17.1-2004 Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators, The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, pp. 1-15.

Chapter 399, Elevator Safety, Florida Statutes, Rule 399.13.

Construction Standards, Miami Beach City Code, Chapter 14, Article 2, Section 14-403 (2009). Ordinance No. 2009-3636, Enforcement of Non-Functioning Wheelchair Lifts.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.