Elevator Ride Quality Adjustment With A VFD

Jul 1, 2019

Properly used, software functions can eliminate effects of rollback and increase speed-control response.

Many people take ride quality for granted when they use an elevator, but a smooth and responsive ride requires precise adjustment from all system components, such as the controller, variable-frequency drive (VFD) and brakes. The VFD can be a powerful adjustment tool for mechanics when properly applied. This article focuses on software functions available in an elevator VFD for two main elevator adjustments: rollback and increased speed-control response.

Rollback

Rollback can occur for a brief moment at the beginning of the ride when the brake lifts, a speed command has not yet been initiated, and the VFD has not built up enough holding torque to prevent the car from moving in the direction of weighting. This may be felt as a bump by passengers in the car during takeoff. Rollback is more noticeable on permanent-magnet gearless motors than on induction geared motors because of the lower starting friction of gearless machines. Rollback can be diagnosed visually if the elevator controller is located in the machine room along with the motor. In machine-room-less (MRL) applications, however, diagnosing rollback may be more difficult, because the motor is out of sight. Inverter scoping software can aid in identifying and adjusting for rollback. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of rollback using a four- channel scope trace showing command speed (red), actual motor speed (blue), motor torque (green) and motor position (yellow).

The motor position (yellow) starts to deviate from zero before the speed command is given, indicating the brake has lifted, and not enough holding torque (green) is present to hold the car at zero speed. Several torque bumps occur in response to motor movement when the brake is lifted, which can cause a bump to be felt by passengers on takeoff.

There are several ways to adjust for rollback. For example, brake and speed command timing may be adjusted such that the car begins to move as the brake is lifting. While this may reduce the effects of rollback, it doesn’t address the root cause and still doesn’t provide a smooth takeoff for passengers. Luckily, depending on the VFD manufacturer, software can be used to eliminate rollback.

Most elevator drive manufacturers have some method of providing a torque command — while under brake or immediately after the brake picks — to eliminate rollback. One method involves using a feedback control loop, which consists of both a proportional and integral coefficient that can be used to provide the motor with adequate holding torque, thus preventing rollback. When this method is used, movement of the car is necessary to make the function work properly. This may seem counterintuitive at first, but the movement is so small, it cannot be seen by the naked eye (as the sheave rotating) or felt by passengers riding in the car. Figure 2 shows a scope trace of torque buildup in response to movement.

Based on the amount of movement detected from the motor encoder, the drive will quickly ramp torque (green) to hold the motor at zero speed. This is done by adjusting the integral coefficient of the feedback control loop, or gain. The integral response accumulates error — in this case, non-zero speed — over time. Higher integral gain values will ramp the torque faster to accommodate the non-zero speed error until a steady-state situation is reached (zero speed). All of this happens very quickly — within 0.3-0.5 s — meaning passengers do not feel anything. This method of providing torque when the brake lifts works very well for most elevator applications, but its basic functionality, a proportional and integral (PI) feedback control loop, relies on error (motor movement) to function.

Another method of providing torque involves using a load weigher. A load-weighing device uses sensors to detect the amount of load in the car and can provide a precise holding torque response based on different loading conditions. Depending on the type of load weigher used, it can connect directly to the VFD and transmit a torque command via an analog signal, or it can be connected to the controller, where further filtering can be applied; then, a resulting torque command can be sent to the drive via serial communication.

Increased Speed-Control Response

For most elevator applications, the standard proportional, integral and derivative (PID) gains in the feedback control loop in a VFD provide adequate speed control-response, but for some high-profile elevator applications (high-end office buildings, apartment complexes, etc.), additional tuning may be necessary to achieve the desired ride quality, such as when set up for aggressive floor-to-floor times. A traditional PID feedback control loop relies on feedback from the motor encoder to make speed control adjustments based on the difference between command speed and actual motor speed from the encoder. This difference is called error. The VFD’s response to this error is adjusted via proportional and integral speed control gains. While this method of speed control works well, it relies on the feedback from the motor encoder for speed control. For some high-performance applications, traditional PI control may not provide the desired speed-control response. For these types of applications, a more sophisticated speed-control method can be used.

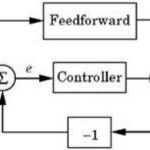

Feed forward torque control (FFTC) can be used to provide added speed-control response. FFTC reduces the dependence on speed feedback from the motor encoder by predicting what the system will do, based on the system inertia, and providing the required torque command based on that prediction (Figure 3).

FFTC can be activated after the system inertia has been learned by the VFD. By modeling the motor data, ysp, and the system response, uff, with the system inertia, a prediction of the response can be made. A pre-correction is made before the motor encoder feedback is received, reducing the amount of error. This method of speed control provides a more accurate response with less reliance on the proportional and integral gains.

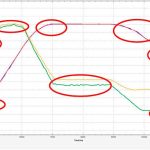

To show how effective FFTC can be, a detuned motor with low-speed control gains and FFTC turned off was set up in a controlled R&D lab setting. No additional adjustments were made to the motor. Figure 4 shows a scope trace of the command speed (red), actual motor speed (blue), motor current (yellow) and motor torque (green) of a simulated elevator run.

Significant amounts of undershoot and overshoot are present on both the acceleration and deceleration portions of the profile (circled). Additionally, these areas of undershoot and overshoot correspond to large torque bumps that can negatively impact ride quality.

Next, to show the impact of using FFTC, the system inertia was learned, and FFTC was activated. The same run was performed and scoped (Figure 5).

Activating FFTC drastically reduces undershoot and overshoot that were present in the acceleration and deceleration portions of the profile. Also, the magnitude of the torque bumps is much smaller, with smoother torque transitions providing a much more comfortable ride. While this is an exaggerated case and done under lab conditions, it shows the basic principle and impact FFTC can have on elevator speed control.

A low pass filter can be adjusted to further improve ride quality. When the speed profile is generated externally by the controller, increasing the sample time of the low pass filter can help reduce any unwanted effects caused by discontinuous inflection points on the speed profile generated by the controller. Additionally, FFTC also features a gain value that can be used to strengthen or weaken its response.

In general, activating FFTC makes the elevator system more responsive. The speed gains will have less effect, and adequate speed control can be maintained over a wider range of gains. FFTC works well in applications featuring aggressive speed-control profiles and applications exhibiting high starting friction, such as geared induction machines.

The elevator VFD is a powerful adjustment tool that can provide solutions to two common elevator ride quality problems. Rollback can be eliminated using a PI control loop in the VFD. Additional tools, such as load weighers, can also be used to eliminate rollback. FFTC can provide added response to achieve desired ride quality in highly dynamic elevator applications. Additional adjustments, such as low pass filters and gains, can fine-tune the ride for the best possible passenger experience.

- Figure 1: Command speed (red), motor speed (blue), motor torque (green) and motor position (yellow)

- Figure 2: Properly adjusted pre-torque settings show no rollback on the scope trace. The illustration shows command speed (red), motor speed (blue), motor torque (green) and motor position (yellow).

- Figure 3: FFTC block diagram

- Figure 4: Command speed (red), motor speed (blue), motor current (yellow) and motor torque (green)

- Figure 5: Command speed (red), motor speed (blue), motor current (yellow) and motor torque (green)

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.