Elisha Otis at Crystal Palace, Part 2

Feb 1, 2022

Historical importance of the 1854 exhibition in New York

Last month’s history article, “Elisha Otis’ Improved Elevator at the New York Crystal Palace,” explored what actually happened at Otis’ 1854 exhibition, as well as the immediate response to this event, which included one newspaper article (in the New York Tribune), one American journal publication (in Scientific American), and two European journal publications (in the Practical Mechanic’s Journal and Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal). While this was an auspicious start, the impact and importance of Otis’ improved elevator and safety device are best measured by examining what happened in the years following the exhibition. This critical part of the story will be explored in an examination of the period from 1855 to 1861. The end date for this investigation – 1861, the year of Elisha Otis’ death – was chosen because of the well-established historical association between the inventor and his invention.

In 1855, Otis’ elevator was featured in a third European journal: The Deutsche Gewerbezeitung republished the text of the article and accompanying image that had appeared in the Practical Mechanic’s Journal; this was followed by a five-year period during which no mention of Otis’ invention appeared in any technical or engineering journals. The year 1855 also saw Otis withdraw the patent application for his improved elevator. Evidence exists that indicates he filed a patent application through the auspices of the Scientific American Patent Agency in October or November of 1854. Although neither his application nor related correspondence with the U.S. Patent Office has survived, it is possible that he withdrew his patent because he was informed that his idea was not “original.”

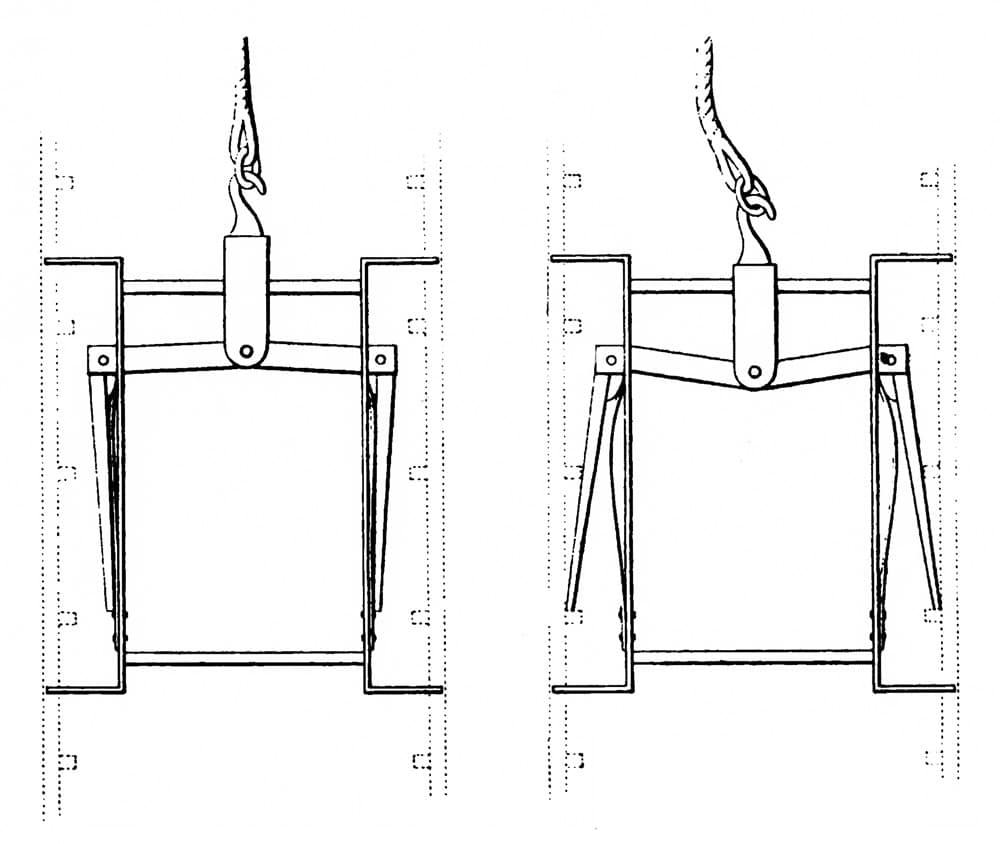

Correspondence associated with Otis’ successful 1860 patent application reveals that the Patent Office had identified a precedent for his safety device, which, as is well known, was a ratchet-and-pawl system designed to prevent the platform from falling if the hoisting rope broke. In 1807, British inventor George Prior had designed a “Machine to Prevent Accidents in Descending Mines.”[1] Prior’s “machine” was a safety device remarkably similar to Otis’. In place of ratchet-like racks, the guide rails featured a center groove into which “strong iron pieces” were attached at set intervals.[1] Pawls or arms mounted on the sides of the platform were held in place by a mechanism attached to the hoisting rope. If the rope broke, springs beneath the arms would push them into the guide rail grooves, where they would engage the iron stops (Figure 1). Circumstantial evidence exists, which suggests that Otis was informed of this precedent in 1855 and that this was why he withdrew his patent application.

The year 1855 also marked the official launch of Otis’ elevator business with the founding of the Union Elevator Works and General Machinery Depot, which was located in space he leased in a recently completed five-story industrial building in New York City. Although the company’s precise location in the building is unknown, it appears likely that it occupied one of the upper-floor loft spaces. In 1856, Otis received permission to install an “Otis steam hoistway” in the building, the use of which was made available to other renters.[2] Thus, visitors to the building would have seen one of his machines in operation. Another event that occurred in 1856, which may have served to further advertise his business, was a second exhibition of an Otis elevator in the New York Crystal Palace. However, this exhibition did not feature Elisha Otis’ improved elevator. Instead, visitors would have seen a “power elevator” designed by Charles R. Otis, Elisha’s oldest son. Unfortunately, almost nothing is known about this exhibition. The only published account of the event simply states that Charles Otis’ elevator was one of the designs that was awarded a “Diploma” by the managers of the Twenty-Eighth Annual Fair of the American Institute.[3]

In 1856, an event took place that may have been inspired by the 1854 exhibition and its subsequent publication in England. However, if Otis was made aware of this event (which is unknown), it is doubtful that he would have embraced the news. In 1856, British architect Hugh Baines received a patent for a version of a ratchet and pawl safety device: Hoisting Machines, British Patent No. 2655 (November 11, 1856). Baines claimed that his invention represented:

“[A] novel method of stopping or retaining the ascending or descending room, chamber, or box employed in “hoists” in warehouses, mills, factories, pits, etc., for conveying persons and goods from one floor or height to another, in the event of the rope breaking, or the occurrence of any other equivalent accident, which would cause or allow the room or chamber to fall to the bottom of said shaft, thereby endangering life and property.”[4]

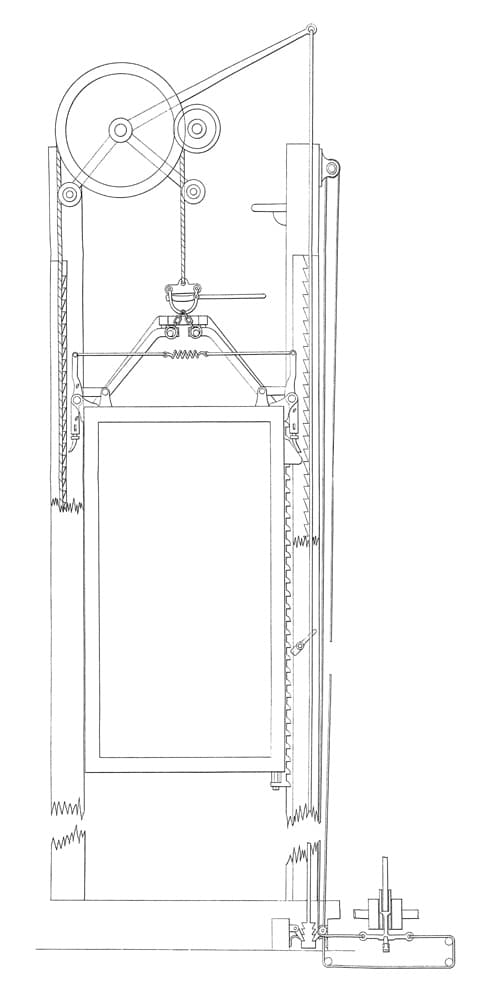

The design employed sliding racks located on each side of the platform that were aligned with the guide rails. If the hoisting rope broke, a mechanism mounted on top of the platform would engage a lever that pushed the platform racks out and up, an action that would cause them to engage racks located on the guide rails. The design also featured a lever mounted on top of the safety that prevented the car from running into the “top gearing.” If the lever was pushed down, it activated the safety racks. Lastly, the design also featured a ratchet attached to the counterweight to prevent it from falling (Figure 2).

Baines was also not alone in seeking a solution to this critical safety concern. Approximately 30 British patent applications were filed between 1855 and 1861 for safety devices designed to stop a platform from falling if the rope broke. While the majority of these inventions concerned elevators used in mines, their persistence in the patent record clearly reveals the perceived importance of solving this problem. It also sheds light on the international context of Otis’ efforts.

While Baines’ direct knowledge of Otis’ design cannot be confirmed, there is no doubt that by the end of the 1850s Otis was a well-known figure in the emerging American vertical-transportation (VT) industry. Although he had not been able to sustain his manufacturing presence in NYC — he returned to Yonkers in 1857 — Otis had sustained steady sales of his elevators. He touted his commercial success in a lengthy December 1859 advertisement that listed all of his sales to-date, which included 118 elevators sold to businesses in 11 states: Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and South Carolina.[5] In the advertisement’s text, Otis also highlighted the merits (and safety) of his products, stating that he kept:

“[C]onstantly on hand, or will furnish to order, at short notice, all kind of machinery — including Otis’ Improved Platform Elevators, for steam, water, hand or other power, so constructed, that if the rope breaks, the platform cannot fall. They have been tested in hundreds of instances without a failure. Ten men have been killed in the city of New York within four years past by breaking of the lifting ropes on the various other kinds, and never a single one with my improved Safety Elevators, although extensively used in every part of the United States.”[5]

Interestingly, the advertisement closed with a statement that appears to indicate that the growing awareness of his elevators did not always solicit positive comments or appreciation. He concluded by stating that “these life-saving elevators, though not appreciated as much as they deserve, are nevertheless growing in public favor, which is more than can be said, with truth, of some other institutions in Yonkers.”[5]

The local targets of Otis’ ire are unknown; however, he was likely aware of criticisms that had been voiced by fellow VT industry members. In May 1859, Boston engineer Albert Betteley received a patent for an air cushion safety device. Betteley’s rationale for his safety was that there was a clear need to supplement existing safety devices, only one of which he specifically identified in his patent:

“The device which consists of rachet racks, on the frame, and pawls, on the car, arranged to operate so as to prevent the fall of the car when the elevating rope breaks, is well known, and is only mentioned here because of its inefficiency in preventing the fall of the car in many cases, as for instance when some part of the machinery gives way beyond the rope, or where, as may be the case, the rope breaks and is subject to sufficient friction to keep the pawls from falling into the rack until the car acquires such a momentum as to destroy the racks and pawls when they act.”[6]

While Betteley’s acknowledgement that Otis’ safety was “well known” may have been welcome news, the implication that the safety did always work as promised was, perhaps, less welcome. Otis’ 1859 advertisement clearly states that, as of December 1859, no fatalities had occurred on one of his elevators. This statement may also be evaluated in the context of the claim that none of his elevators had “failed,” perhaps meaning that the safety had consistently acted to prevent a fatal accident; how well the safety actually performed when needed is less clear.

Otis’ decision to run a lengthy advertisement in late 1859 may have been prompted by a slow-down in business. On July 23, 1860, Charles Otis recorded in his personal journal that “Two years have passed since I last wrote in my Journal. And two eventful years … Our hoisting machine business increased … so that we just managed to keep our heads above water and we gradually got out of difficulty.”[7] In addition to seeing a modest rise in business, 1860 also saw Otis’ return to the pages of Scientific American: the September 8 issue included an illustrated article that described a steam engine developed by Elisha and Charles Otis. The engraving of the engine was described as having been based on a machine “in operation at the new and elegant jewelry store of Messrs. Ball, Black & Co., on Broadway, where it is used principally for hoisting goods.”[8] Interestingly, the article did not include any overt references to the fact that the engine was used to power one of Otis’ improved safety elevators, and the illustration provided no visual references to the elevator platform or safety (Figure 3).

In 1860, Otis also launched, once again working with the Scientific American Patent Agency, a second attempt to patent his ratchet-and-pawl safety. The patent application was submitted on August 15, and on August 24 Otis received notice that his invention was “not patentable as presented.”[9] The patent office cited the George Prior 1807 precedent and, ironically, Otis’ withdrawn 1854 patent as reasons for denying the application. However, this time Otis refused to accept this decision and, with the support of Scientific American — which entailed several additional letters, revisions to the patent text, and an in-person meeting with patent officials in Washington, D.C. — Otis succeeded in securing approval for his patent on January 2, 1861 (the date of the published patent was January 15, 1861).

The February 2, 1861, issue of Scientific American included a brief announcement of Otis’ patent that described the essence of the invention:

“The object of this invention is to obtain a hoisting apparatus which may have its weight or load readily stopped at any desired point, and a brake automatically and simultaneously applied with the stopping of the weight or load. The invention also has for its object the sustaining of the load or weight in case of the breaking of the lifting rope, in such a way as to insure a certain effectual action or operation of the load-sustaining mechanism. The invention has further for its object the counterpoising of the platform in such a way that, in case of the breaking of the lifting rope, the connection of the counterpoise will not interfere in the least with the load-sustaining mechanism. The inventor of this device is E.G. Otis, of Yonkers, N.Y.”

This account is of interest in that it includes no references to Otis’ 1854 exhibition or his manufacture of safety elevators. It simply lists the three objectives found in his original 1860 patent application, the last of which was denied by the Patent Office and omitted from the approved patent. Unfortunately, Elisha Otis had only a few months to celebrate the patenting of his safety device. In early April, he contracted diphtheria and died on April 8, 1861, at the age of 49.

Otis’ safety device and its 1854 exhibition is often heralded as the event that launched the modern era of VT. The examination of this event and its aftermath has revealed that:

- It received modest national and international recognition.

- It gave Otis the opportunity to develop his elevator business.

- It may have inspired others to develop similar safeties.

- It became a well-known elevator safety device in the U.S.

- It may not have always worked as intended.

Of these findings, perhaps the most important is that it allowed the creation of a fledgling elevator company that Otis was able to pass on to his children. This gave Charles and Norton Otis the opportunity to gradually develop their father’s business into one of world’s leading elevator manufacturers.

Was this single event the watershed moment in modern VT history? No. Was it important in setting the stage for future events? Yes. Of course, missing from this investigation is any reference to building a passenger elevator, another “first” consistently attributed to Elisha Otis. As was noted in my book, From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators (EW 2001), no published accounts of Otis installing a passenger elevator during this period were found, nor were any such accounts discovered in this recent investigation. The question of when the first passenger elevator installation in the U.S. occurred — and who built it — are questions whose answers must wait for another day and a future article.

References

[1] Transactions of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce; With the Premiums offered in the year 1818, V. 36 (1819)

[2] Advertisement for space to lease in 117 Franklin Street, New York Daily Herald (March 10, 1856).

[3] “Premiums awarded by the managers of the Twenty-eighth Annual Fair of the American Institute, at the Crystal Palace, 1856 (Machines, models and inventions),” The Inventor (December 1, 1856).

[4] Hugh Baines, Hoisting Machines, British Patent No. 2655 (November 11, 1856).

[5] Otis Advertisement, Yonkers Examiner (December 15, 1859).

[6] Albert Betteley, Elevator, U.S. Patent No. 23,818 (May 3, 1859).

[7] Donald Shannon, The Annuals of Vertical Transportation, Otis Elevator (unpublished manuscript dated January 1953).

[8] “Improved Oscillating Engine,” Scientific American (September 8, 1860).

[9] Letter from U.S. Patent Office to E.G. Otis (August 24, 1860).

[10] “Recent American Inventions: Hoisting Apparatus,” Scientific American (February 2, 1861).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.