Elisha Otis’ “Improved Elevator”

Jan 1, 2022

Examining the “facts” from the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition

The story of Elisha Otis’ exhibition of his “improved elevator” at the New York Crystal Palace in 1854 is found in almost every history of vertical transportation. And, in almost every instance, the same limited number of facts are presented: Otis demonstrated his safety by riding up and down on the elevator platform, and he would occasionally cut the hoisting rope, which caused his rachet-and-pawl safety device to activate, after which he would shout, “All safe, gentlemen, all safe” to an astounded audience. Some tellers of this story also add that it was none other than the great P.T. Barnum who paid Otis to exhibit his invention in such a dramatic fashion. Lastly, almost everyone who has recounted this story has claimed that this single event marked the origin of the modern elevator. These “facts” are the essence of the story that has been consistently told since the mid-20th century. However, a close examination of these stories reveals that its acceptance as “true” relies more on faith and trust in the storytellers than on actual evidence. This prompts two important questions: What really happened in 1854? And, what was the importance of this event?

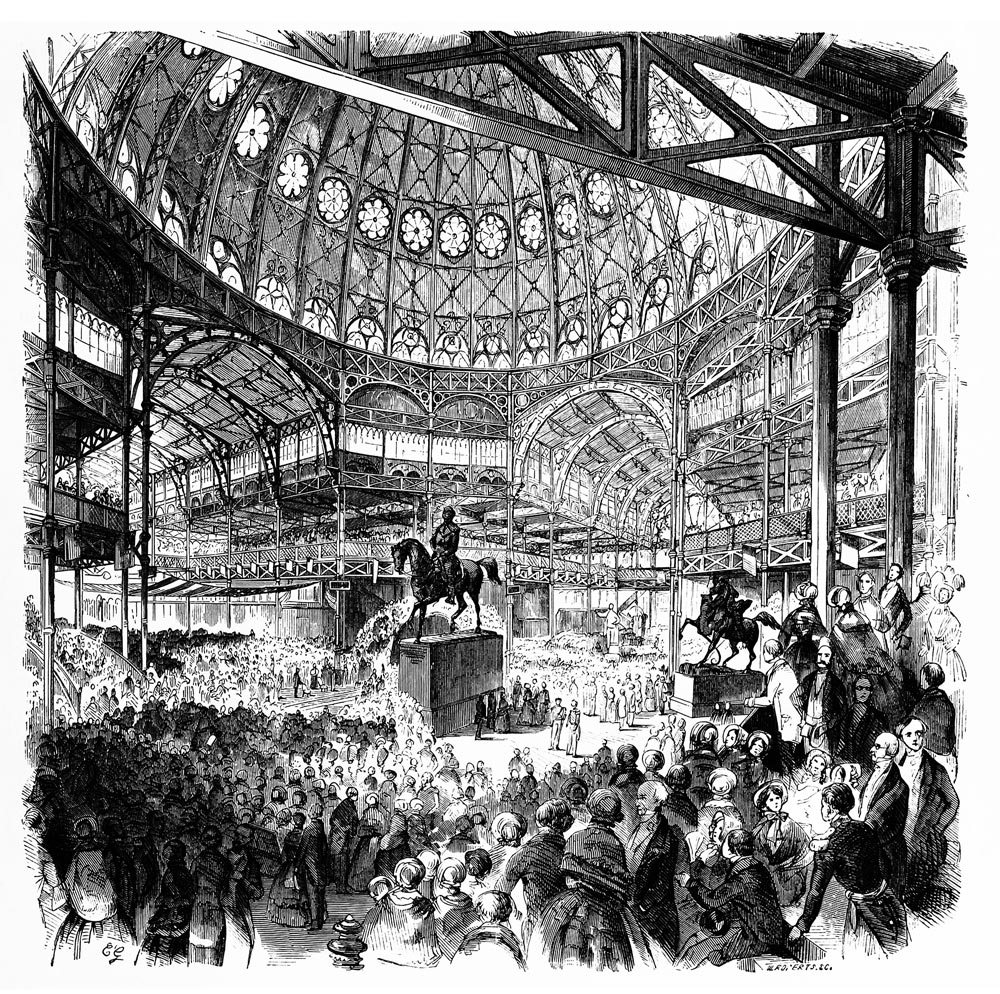

The New York Crystal Palace was built in 1853 in response to the first Crystal Palace, which was built in London to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. This event marked the first international exhibition focused on art and design and, while it featured exhibits from all over the world, its primary function was to showcase the superiority of British industrial designs and products. The exhibition’s success prompted other industrialized countries to sponsor similar events. The design of the New York Crystal Palace followed the paradigm established in London, and the building consisted of a massive green-house-like structure with exposed interior structural elements (Figures 1 & 2). The building and exhibition opened on July 4, 1853. Unfortunately, its financial success was far less than its promoters had hoped. This led to a reorganization of the Crystal Palace Association in early 1854, which included the selection of Phineas T. (P.T.) Barnum as association president. It was hoped that Barnum’s well-known promotional skills and sense of showmanship would provide the spark needed to ensure future financial success.

In an open letter to the directors of the Crystal Palace Association published in early April 1854, Barnum announced that the building would be closed beginning April 15 to prepare for its grand “re-inauguration” on May 4. The proposed improvements outlined in the letter included the claim that:

“The Machinery Department will be much fuller and more effective than hitherto. There will be operating specimens of nearly every great invention. . .As steam power will be furnished for the most interesting processes in art and industry, and as inventors and exhibitors will be permitted, under certain judicious regulations, to run machinery for their own benefit, this branch of the exhibition is expected to become especially interesting.” [1]

This provides the first hint of the character of the setting that Otis would encounter. The ability to easily access steam power was a critical factor in the exhibition of working industrial systems. Barnum’s vision for the reimagined Crystal Palace also included continuation of a practice established by prior exhibitions: awarding prizes.

Prizes for items exhibited in the Machinery Department included a gold medal valued at US$1,000 and five gold medals valued at US$100 each. The US$1,000 gold medal would be awarded to “the most useful and valuable invention or discovery which shall have been patented or entered in the U.S. Patent Office during the year closing on the first day of December, provided only that the said invention or discovery, by specimen, model, or product, shall have, meantime, been exhibited in the Crystal Palace.”[2] The other medals would be awarded to “the five inventors whose inventions in the various departments of useful arts, patented, entered, or caveated within the year, and shall be exhibited in the Crystal Palace as foresaid, and shall be adjudged most worthy of such distinction.” [2]

Barnum also announced that he had been “authorized to announce that the Association will, at their discretion, award medals or diplomas to the exhibitors or inventors of such articles as possess merit sufficient to entitle them to such distinction.” [2]

The first public announcement of these prizes was made in the speech Barnum gave at the re-inauguration ceremony on May 4. Interestingly, no evidence has been found that prospective exhibitors received prior notification of these powerful incentives to display their inventions and designs. The timing of the announcement suggests that Barnum may not have received the number of exhibits for which he had hoped with regard to the Machinery Department. Thus, he felt the need to offer these incentives.

Otis committed to exhibiting his elevator prior to the announcement of these awards (although he was doubtless pleased to learn about them and likely hoped to garner one). He may have been prompted to consider exhibiting his invention by reading Barnum’s circular to the exhibitors at the Crystal Palace (dated April 15) which stated that, “The earliest possible transmission of all articles intended for exhibition, at and after the reopening, is urgently solicited.” Otis’ account book for 1854 lists the receipt of US$100 for “one model hoist machine,” which was “sent” to the Crystal Palace on May 5. [3] This suggests that the model hoist (presumably a scaled-down version of a full-size machine) was built between mid-April and May 5. Unfortunately, the account book gives no indication of who commissioned the model or provided the money to support Otis’ efforts to exhibit his invention. While it has been suggested that Barnum provided these funds, no evidence has been found that indicates that either Barnum or the Crystal Palace Association provided financial support to exhibitors. Thus, Otis’ benefactor remains unknown.

The model hoist was shipped on Friday, May 5. It may be reasonable to assume that the exhibit installation was complete by mid-May. Once the installation was finished, Otis faced an interesting decision regarding how and when he would present his work. The Crystal Palace was open seven days a week, from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. It is doubtful that Otis was present 14 hours a day, seven days a week, displaying his hoist. Additionally, the length of time it was exhibited is unknown. While a newspaper account confirms its presence at the end of May, it seems unlikely that the exhibit remained in place until September, when the exhibition season closed. In fact, it may have been removed by Otis in mid-June. In 1911, Charles R. Otis wrote an account of his father’s life that claimed the exhibition had an immediate impact on business, which resulted in orders for new hoists beginning in early June. He further stated that “from this time on, the business gradually extended” and his father gave his “entire time and energy to it.” [3]

The question of how Otis demonstrated his hoist was answered in the first published account of his exhibit. A May 30 article that appeared in the New York Tribune stated Otis’ exhibit attracted “attention both by its prominent position and the apparent daring of the inventor, who, as he rides up and down upon the platform occasionally cuts the rope by which it is supported.”[5] Charles Otis also recalled that the exhibit was located “in a conspicuous place” and that:

“The platform was sufficiently large for him (Elisha Otis) to stand upon and work the machine, which had a vertical movement probably of from thirty to forty feet. During this exhibition, Mr. Otis stood upon the platform, ran the machine up to a considerable height, then cut the rope, his safety appliances preventing the platform from falling, thus demonstrating the value of his invention, and making his exhibit one of the most interesting and attractive in the fair.” [3]

It should be noted that neither account included any references to what Otis may have said while demonstrating his hoist and safety device. Additionally, no contemporary drawings or photographs have been found that illustrate Otis’ exhibit.

While the significance and/or importance of Otis’ demonstration is difficult to determine, it is of interest that the second account of this event appeared in a British trade magazine. The July issue of the Practical Mechanic’s Journal included an overview of machinery exhibited in the New York Crystal Palace. The Journal’s correspondent reported that:

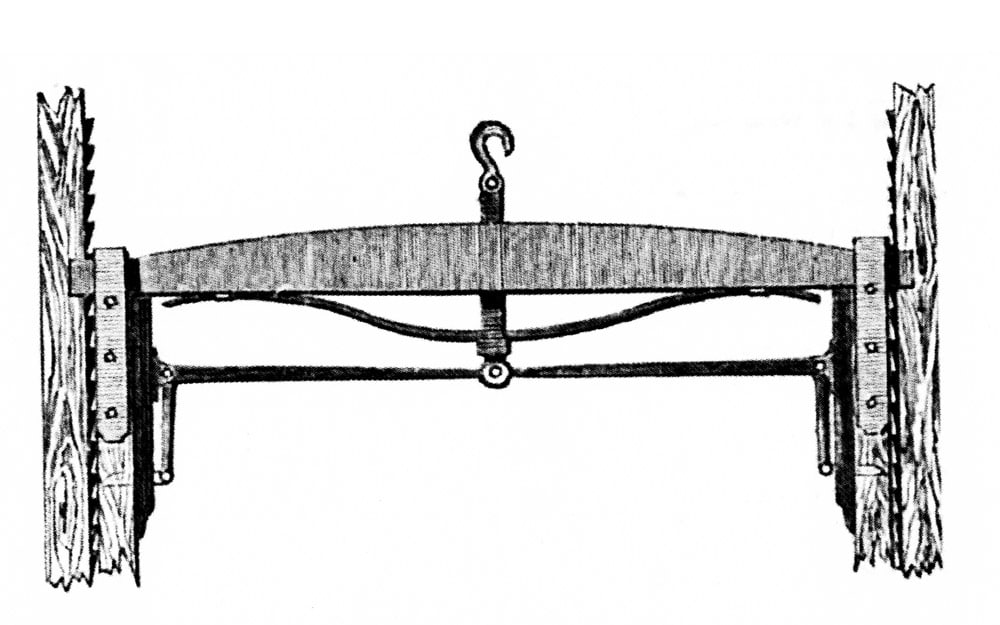

“The moving platform is guided by uprights of wood in the usual manner, but the inner side of each is provided with a row of rachet teeth. The upper portion of the frame carries a set of pads, which, in their normal position, are drawn back by the tension of the rope or chain sufficiently to clear the rachet teeth. In case of breakage, however, of the rope, the pads would immediately be thrown forward by a stiff spring, and, taking hold of the rachet teeth, would sustain the platform without injury. The rope is frequently cut by the exhibitor whilst he is himself on the platform, in order to show its operation.” [7]

This account was accompanied by an illustration that depicted the safety device located atop the platform (Figure 3). The origin of this drawing, which constitutes the first published image of Otis’ invention, is unknown. The image has not been found in any contemporary American source, thus it appears to have been produced specifically for this publication. It may have been made by the Journal’s correspondent or it may have been provided by Otis. The image and the contents of the British article were republished in a German technical journal in December, which included the observation that similar safety devices had been employed in elevator shafts for a long time. [7] Unfortunately, the unknown author provided no additional information on this statement, which questioned the originality of Otis’ design.

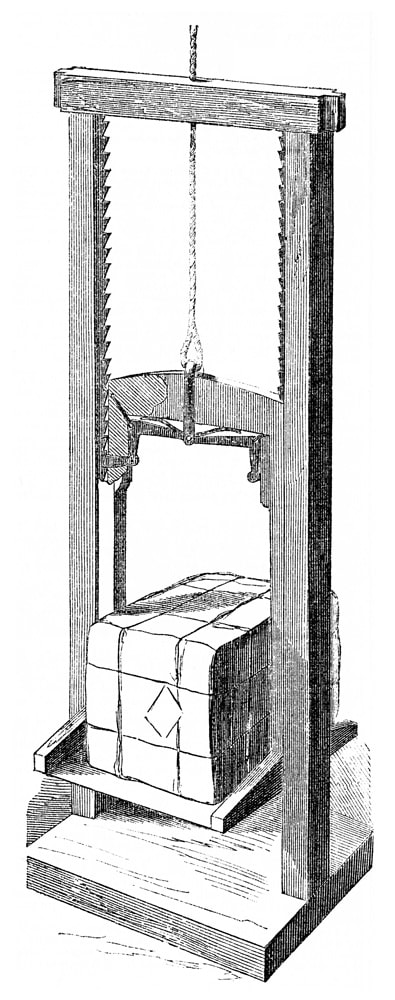

The November 25, 1854, issue of Scientific American featured the first illustrated account of Otis’ hoist published in the U.S. While the article’s primary focus was a detailed description of the safety’s design and operation, in his conclusion, the author noted that “this excellent platform elevator was on exhibition in the Crystal Palace during the past season, and was much admired.” [8] The illustration was a perspective of the hoist that depicted the platform, guide rails and safety device (Figure 4). The article also noted that Otis had “taken measures to secure a patent” for his invention.[8] This action is not surprising, given that this was one of the criteria established by Barnum for award consideration. Otis was also, quite probably, anxious to protect his design. While no record exists of who won the awards established by Barnum and the Crystal Palace Association (or if they were awarded), no evidence has been found that suggests that Otis was considered for any award.

This examination confirms that Otis exhibited his elevator in the dramatic fashion typically described in most stories of this event. However, it did not discover any evidence regarding what Otis may have said during his demonstration, thus the claim that he shouted, “All safe, gentlemen, all safe,” remains unverified. Additionally, the idea that P.T. Barnum sponsored Otis’ display is unsupported by the facts discovered thus far. The appearance of brief illustrated accounts of his invention in British and German journals — events that marked the first international publication of an American elevator — suggest that his design may have been perceived as an important innovation. However, the impact and importance of Otis’ improved elevator and safety device are best measured by examining what happened next, in the years immediately following the exhibition of 1854. This critical part of the story will be the subject of next month’s article.

References

[1] “New York Crystal Palace: To the Directors of the Crystal Palace Association,” The New York Times (April 17, 1854).

[2] “Labor and Art: Re-Inauguration of the Crystal Palace,” The New York Times (May 5, 1854).

[3] Donald Shannon, The Annuals of Vertical Transportation, Otis Elevator (unpublished manuscript dated January 1953).

[4] “Circular to the Exhibitors at the Crystal Palace,” The New York Times (April 17, 1854).

[5] “Science, Industry and Invention,” New York Tribune (May 30, 1854).

[6] “Monthly Notes: American Notes, By Our Own Correspondent,” The Practical Mechanic’s Journal (July 1854).

[7] “Sicherheits-Aufzug für Waarenmagazine,” Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal (December 1854).

[8] “Otis’ Improved Elevator,” Scientific American (November 25, 1854).

[9] George Carstensen & Charles Gildemeister, New York Crystal Palace. Illustrated description of the Building, New York: Riker, Thorne, & Co. (1854).

[10] The World of Science, Art, and Industry Illustrated from Examples in the New York Exhibition, 1853-54. Editors: B. Silliman, Jr. & C.R. Goodrich, New York: G.P. Putnam & Company (1854).

Also read Elisha Otis at Crystal Palace, Part 2

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.