Fred Anzley Annett

Jul 1, 2024

A look at the life of the “dean” of VT writers

The January 1960 issue of ELEVATOR WORLD included a special edition of William C. Sturgeon’s monthly editorial column “Speaking of Issues,” which was subtitled “Fred Annett — A Personal Loss.”[1] The column memorialized Annett’s life and character, which Sturgeon summarized as follows:

“Fred Annett was a teacher above all. Starting with the beginnings of a grade school education, he taught himself arithmetic, algebra and geometry. When he had gone as far as he could on his own, while holding down a 12-h-a-day job, he turned to correspondence courses and then to a New York night school. He became a master teacher of practical electricity; an acknowledged authority on hydro-electric power; on pumps and mechanical power; and, of course, he was the ‘dean’ of writers on elevatoring.”[1]

Annett’s primary contributions to elevator literature included Electric Elevators: Their Design, Construction, Operation and Maintenance (first edition 1927, second edition 1935) and Elevators: Electric and Electrohydraulic Elevators, Escalators, Moving Sidewalks and Ramps (1960), which was marketed as the third edition of his earlier works. All of his books were published by McGraw-Hill. While these works may have established him as the “dean” of vertical-transportation (VT) writers, Sturgeon’s brief summary of Annett’s career did not shed light on why he decided to focus some of his considerable talents on elevators. The answer to this question is found in his remarkable personal journey that began in Canada.

Annett was born on August 26, 1879, near Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, and he grew up in the farming village of Lakeville. In 1896, at age 16, he left Lakeville and the prospect of farm life behind and moved to Fredericton, the capital of New Brunswick, to work in a sawmill. After the mill closed in the fall, he left Canada (for good, as it turned out), traveling south to Berlin, New Hampshire, where he first found work pumping water out of an excavation on a construction site; this job was followed by carrying a brick hod for a company building a paper mill. In December 1896, he moved to Franconia, New Hampshire, where he found a job with a local sawmill, working in the woods during the winter and in the sawmill during the summer.

In the spring of 1899, Annett moved to Gardiner, Maine, and he worked in the Berlin Mill Co.’s sawmill in neighboring Farmingdale. By this time, Annett had learned a specific and highly skilled job in this dangerous industry. In a sawmill, individual logs were placed on a carriage that fed them back and forth through a band or circular saw as individual boards were sawn off. Annett rode the moving carriage working as a setter. He was responsible for moving a log:

“into position for each successive line to be sawed. This (was) … accomplished by means of a ratchet connected with the head blocks by a shaft and cogs. The ratchet was turned by a lever and had a graduated dial and indicator by which the setter determined when the log was in position for the desired cut.”[2]

The mill’s supervisor was a fellow Canadian, James C. (Jim) McGraw (1865-1956), who was known for working his crews particularly hard. This led to Annett’s involvement in his first, and perhaps most unusual, achievement. On September 21, 1899, Annett was a setter on a team that, using a single saw, cut 158,601 board-feet of lumber in an 11-h shift — a feat that was described as a new world record. News of this accomplishment was picked up by the Associated Press and brief notices appeared in newspapers across the U.S.

Not long after this event, and what must have been an especially challenging workday, Annett left Maine with the intention of traveling south to Mobile, Alabama. The reason for selecting this particular destination remains a mystery and, in fact, he got no further than South Carolina. Following a brief stop in Stoughton, Massachusetts, to visit his uncle, he traveled to Washington, D.C., where he bought a train ticket for Georgetown, South Carolina. Located north of Charleston on the coast, the city was the site of a newly completed sawmill. When he arrived in Georgetown, he found that his former boss, Jim McGraw, was in charge of the new mill, and McGraw immediately hired Annett to work as a setter. McGraw’s aggressive supervisory habits hadn’t changed, and Annett left the city two days after his arrival. He returned to Franconia, New Hampshire, where he resumed working for the local sawmill.

By late 1900, Annett had decided that he needed to find a new line of work. In January or February 1901, he traveled to Paoli, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia, seeking employment as a brakeman with the Pennsylvania Railroad. Unfortunately, no work was to be found there, and he was advised to try the Pennsylvania Railroad’s freight yard in Jersey City, New Jersey. Upon arrival in the city, he met yardmaster Frank McNally (1851-1904), who, after a brief interview, offered him a job as a switchman. While Annett had sought employment as a brakeman, his lack of experience with railroads prompted McNally to offer him the other position. It’s worth noting that Annett was attempting to move from one dangerous job — a sawmill setter — to an even more dangerous job: a railroad brakeman. This insight into his character speaks to a willingness to take on the most challenging work available.

Annett worked at the freight yard until 1906. During his time there, he advanced to the position of brakeman, and he also began to realize that this was not the career or life he wanted. His “way out” began by seeking to expand his educational horizons. This was, at first, a self-driven exercise: He purchased a book on basic arithmetic, which was followed by books on algebra and geometry. The next step was to enroll in a course offered by the American School of Correspondence, which was associated with the Armour Institute in Chicago. Why he chose to study mathematics and what correspondence course he took is unknown. What is known is that Annett disliked the correspondence course because it lacked real-time engagement with teachers and hands-on experience. This led him to leave his job in April 1906 and enroll full-time in a trade school.

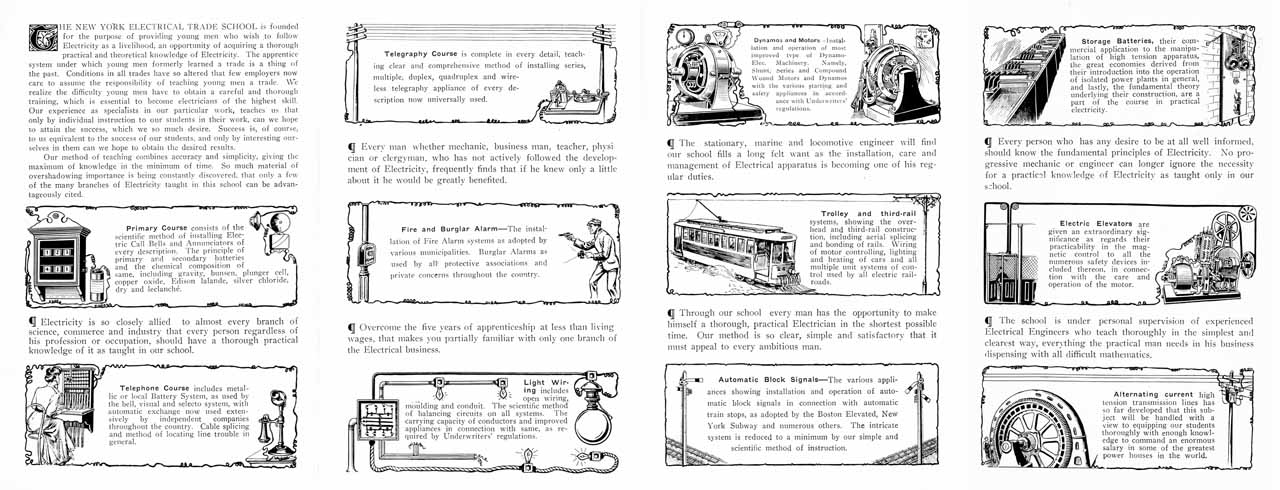

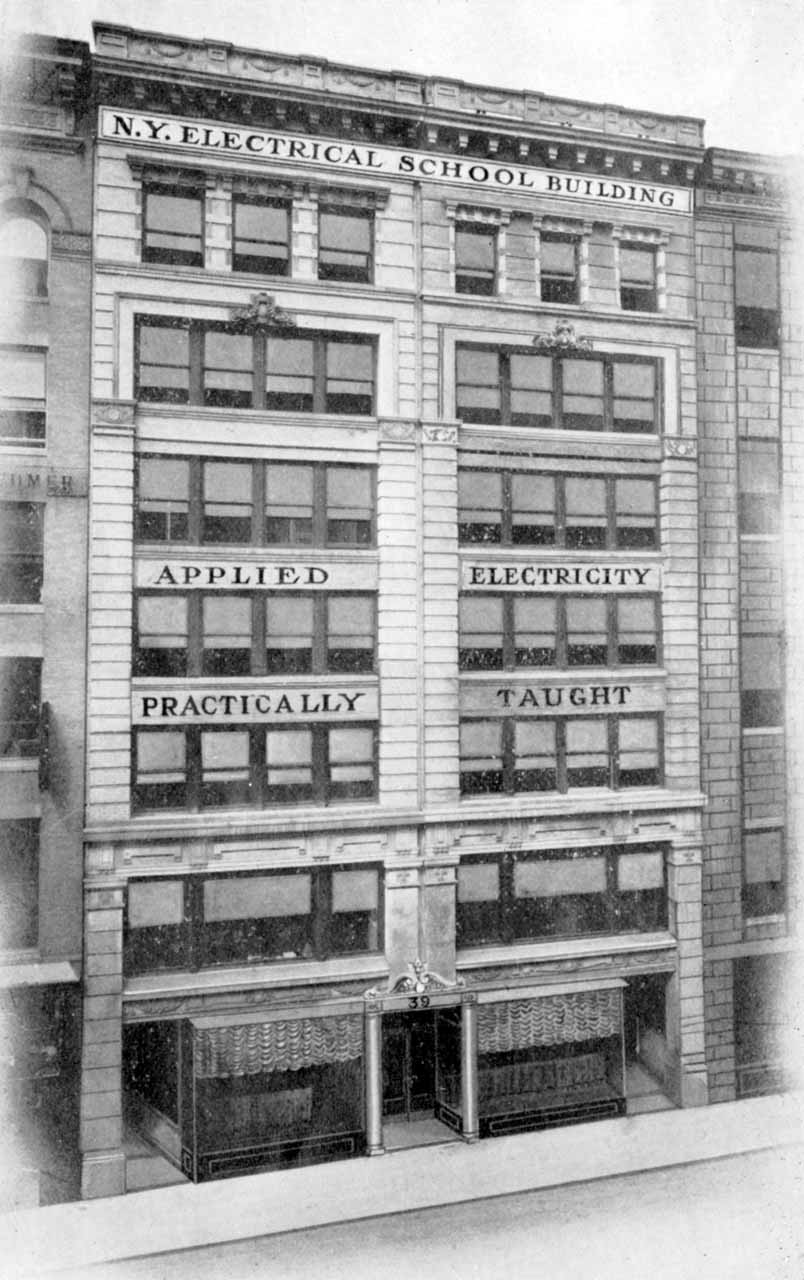

His choice of school was driven by location — he did not want to leave the NYC area — and by the subject of study offered — so he enrolled in the recently established New York Electrical Trade School. Why he chose to pursue an education in the emerging electrical field is yet another unknown aspect of his early career. He may have been inspired to apply by reading one of the countless advertisements promoting the school, which stated: “Men and boys to learn electrician’s trade. Practical courses day and evening. Positions guaranteed. Call or write for catalogue. New York Electrical Trade School, 127 West Forty-second St., New York City.”[3] Annett likely contacted the school requesting a catalog prior to enrolling. If he did so, he would have received a form letter that described the school’s offerings with almost breathtaking enthusiasm:

“In order to thoroughly impress upon you the value of our systematic training, I find it necessary to write a rather long and, I trust, not uninteresting letter. I feel sure that you will read it through carefully and respond promptly, as prompt action is the keynote of success. At the present time, there is no other branch of industry that offers one-half the opportunities for profitable employment and advancement than are to be found in the electrical field.” [4]

This introduction was followed by an overview of the school’s offerings, information that was also summarized on the letterhead, which described the school as:

“The only practical engineering trade school. Practical lessons taught in the following: dynamo-electric machinery, interior lighting and power wiring, installation and care of alternating and direct current power plants, electric elevators, pumps, fans, motors and heating appliances, telephones, telegraph annunciators, bells, etc.”[4]

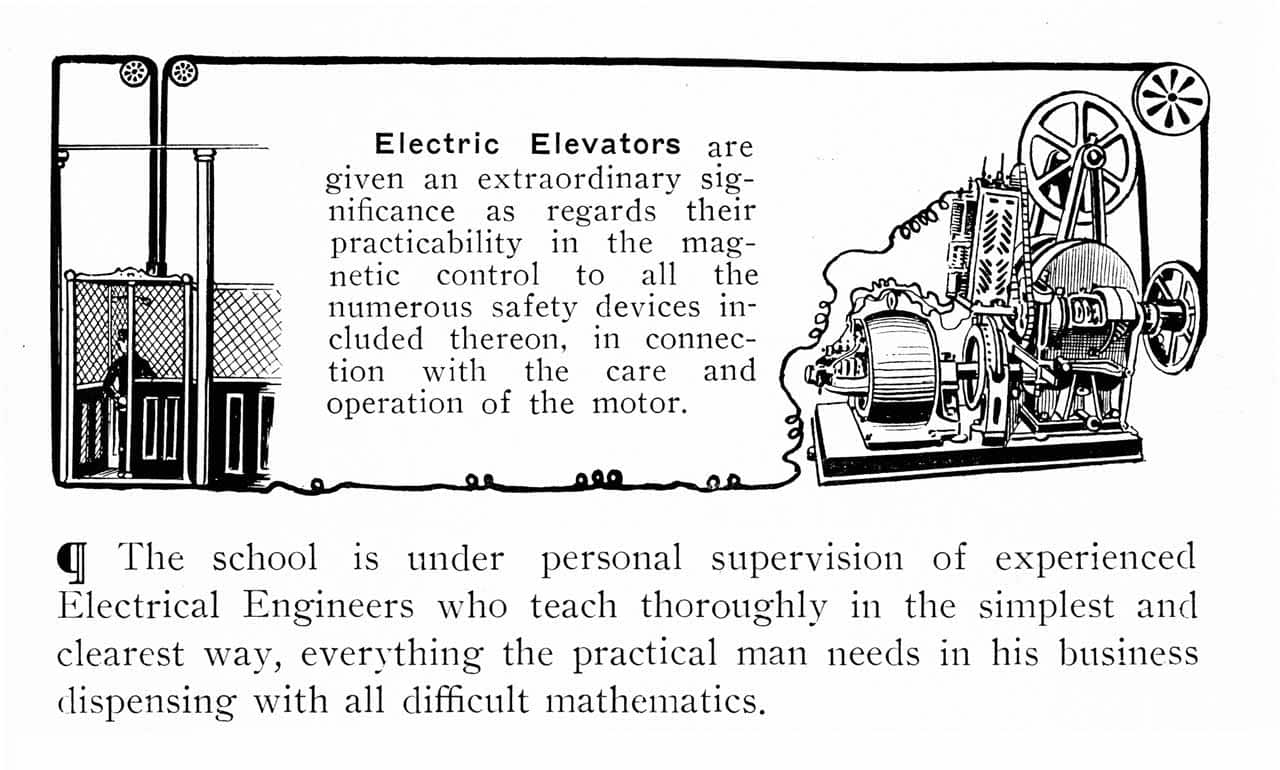

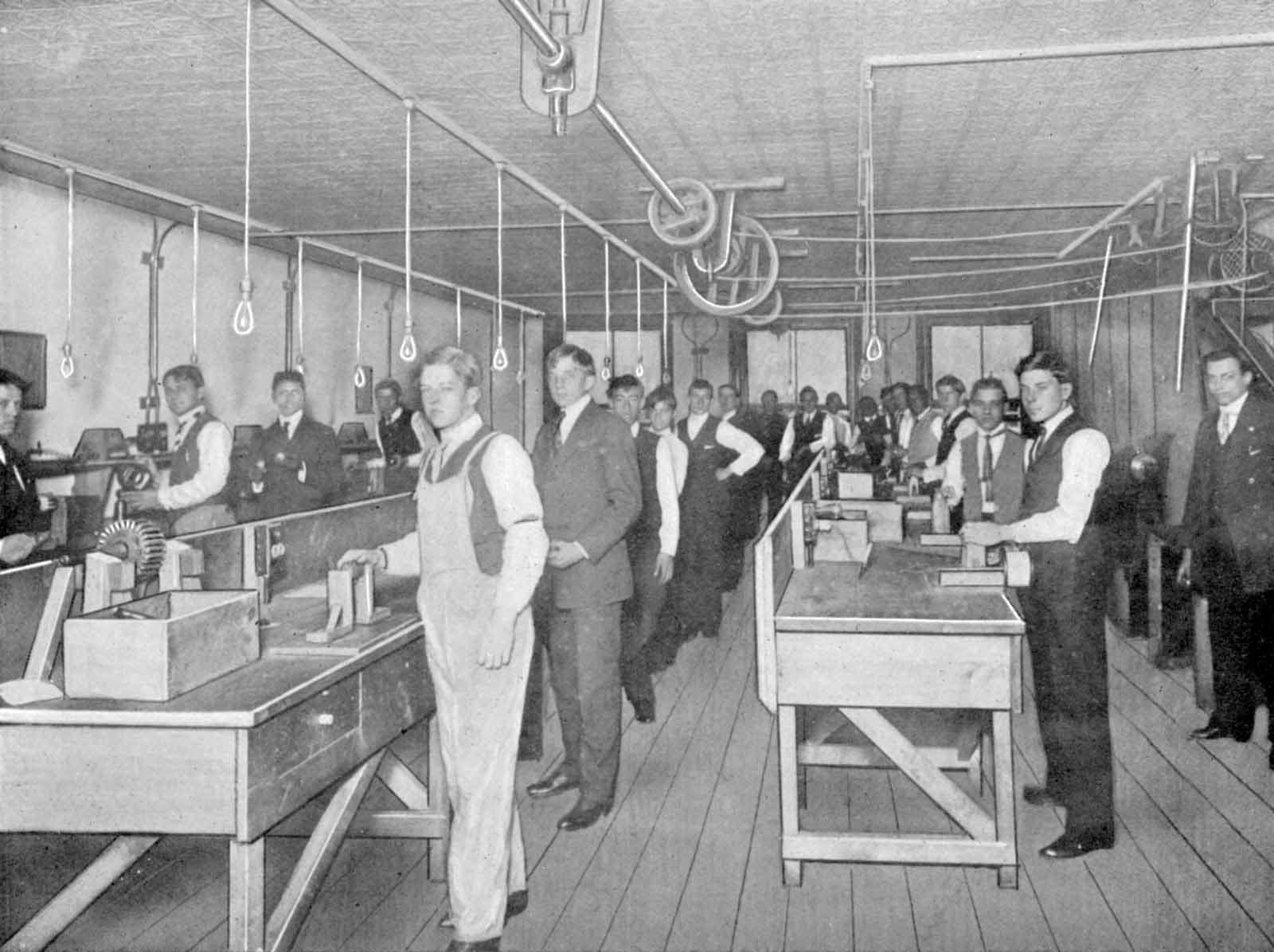

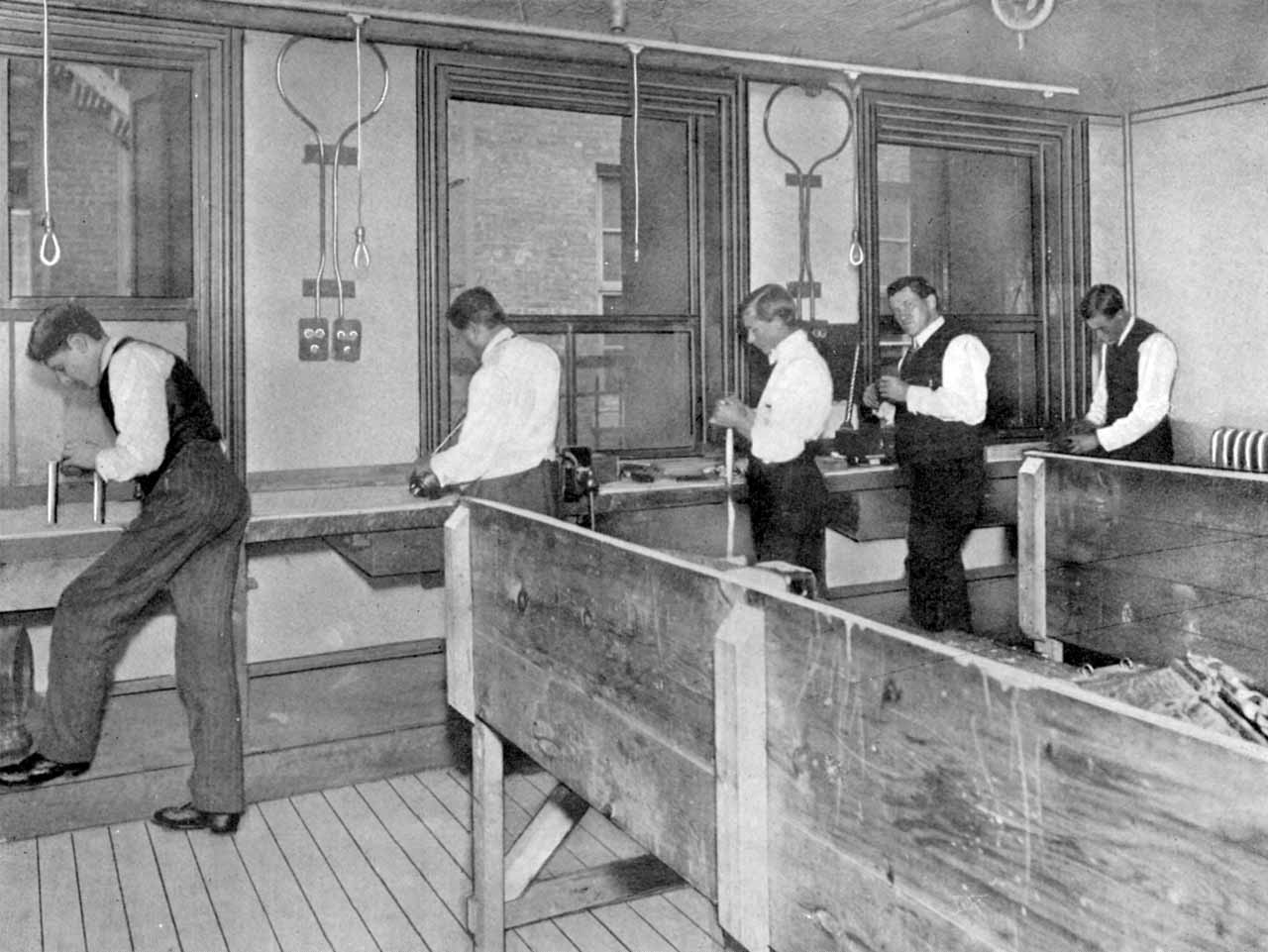

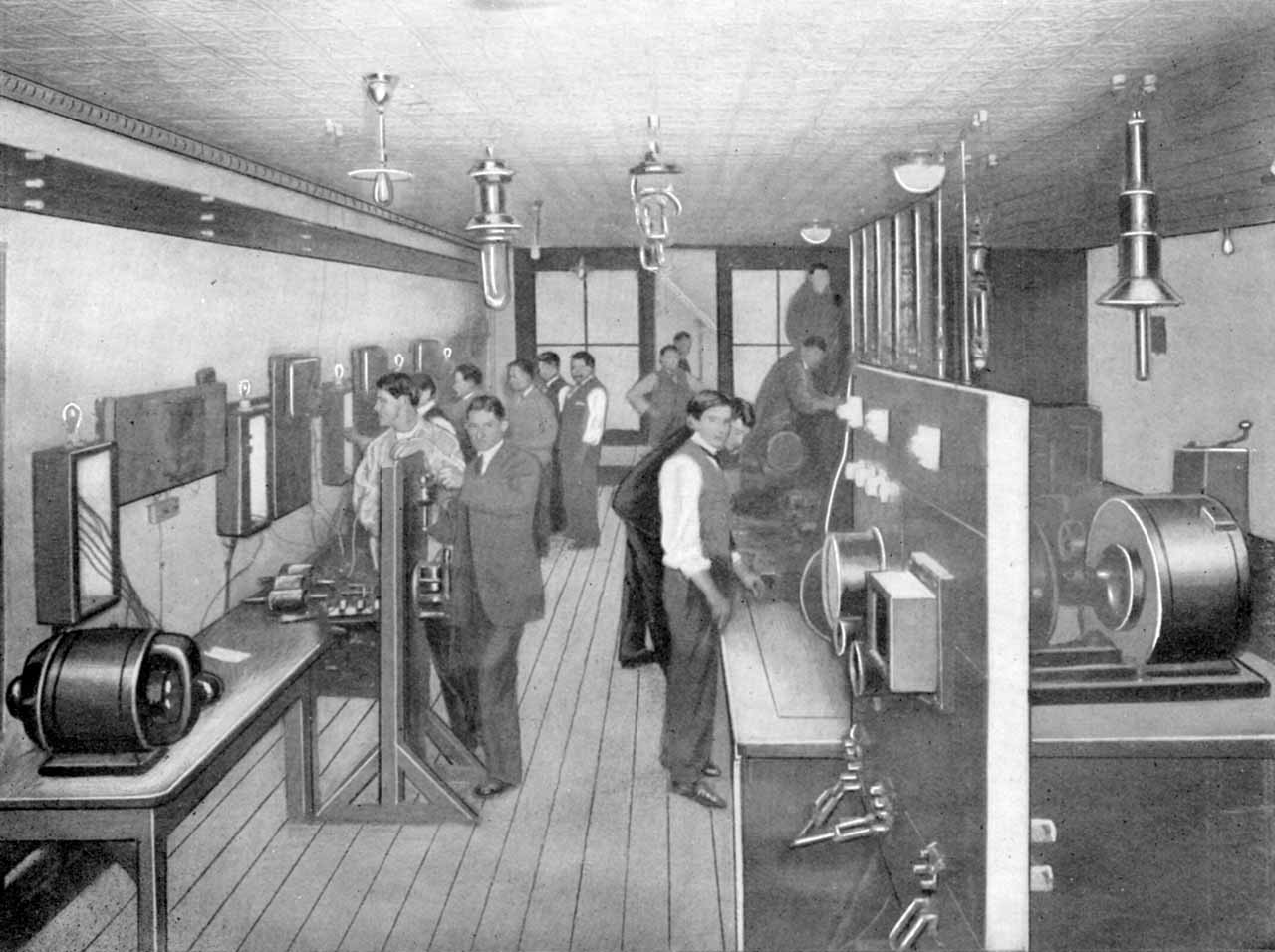

The accompanying illustrated catalog featured brief descriptions of the various subjects of study (Figure 1). The study of electric elevators was summarized as follows: “Electric elevators are given an extraordinary significance as regards their practicability in the magnetic control to all the numerous safety devices included thereon, in connection with the care and operation of the motor” (Figure 2).[5] As Annett was soon to find out, the awkward wording of the elevator course description, which was echoed in other course descriptions, proved to be a hint that the school was not quite as rigorous as advertised.

When Annett enrolled in April 1906, the school occupied one floor of a building on West 42nd Street. In September, the school signed a 21-year lease on a new seven-story building on 17th Street. The move was completed by January 1907, with the school occupying all seven floors. However, during this period, Annett had grown increasingly dissatisfied with the quality of instruction, a sentiment shared by his fellow students. His response to the situation was to offer himself up as a teacher, and by January 1907, he was working as an Instructor of Electrical Drafting. While he could affect some positive change in his new role, he eventually recognized that, under the school’s current management, remaining problems would not be addressed, and in November 1907, he threatened to resign. This action had an unexpected result. Desiring to keep him at the school, the Board of Directors fired the school’s founding president and manager, hired new leadership and appointed Annett to the post of Instructor of Electrical Machinery.

It is important to note that, at this time, Annett possessed only a theoretical understanding that was reinforced by hands-on, “practical” experience in the school’s classrooms and shops (Figures 3–5). While these facilities did offer a practical education, they were not the equivalent of actual experience “in the field.” To remedy this deficit, Annett sought to expand his understanding of electrical machinery outside of his academic setting. In early 1909, he sought and found weekend work (he was teaching five days a week at the school) with the Maintenance Co., a firm that specialized in elevator installation and repair. In fact, he offered to work without pay (an offer the company accepted), because he saw the opportunity as a learning experience. The reason why Annett chose to work on elevators is unknown. It’s possible that he had studied or been exposed to them at his school; however, no detailed information has been found regarding the program of elevator education offered nor has the instructor been identified.

Annett’s decision to pursue employment at the Maintenance Co. provided the best “real life” VT education available. Not only did the company work on a wide variety of machines built by different manufacturers, his supervisor also likely served as an excellent instructor. In May 1909, the Maintenance Co. hired Frank M. Coffin (b. 1869) as their new superintendent of Construction and Repairs. He had attended City College (New York) and the Cooper Institute before taking a position as an apprentice with Whittier Elevator Co. (Boston) in 1887. In 1892, he joined D.H. Darrin Co. (New York). This was followed by employment with the Automatic Switch Co. (New York) where he designed and oversaw “the construction of elevator mechanisms and automatic controlling devices.”[6] In the years immediately prior to joining the Maintenance Co. he had been employed by Otis’ New York office in their construction department. While employed, Annett also continued his education by taking evening classes at the Pratt Institute.

Annett stayed with the Maintenance Co. for three-and-a-half years. It was during this time that he discovered his future employer: McGraw-Hill, publisher of Power magazine. The Maintenance Co. was contracted to maintain the electrical equipment at McGraw’s publishing plant, and during one of his visits, Annett saw a copy of Power on one of the presses. By mid-1912, Annett felt that he had gained sufficient real-world experience and returned to his school and former post as an instructor in Electrical Machinery. During his absence, a fundamental change had occurred in the school’s educational mission, which was signaled by changing its name to the New York Electrical School:

“The New York Electrical Trade School will be advertised and known as The New York Electrical School. The reason for this change is that they are communicating knowledge, which is in advance of a trade, and at the same time following a new system, which is a departure from that originally followed by the school.”[7]

In fact, the name change happened not long after he left the school, and by the time he returned, the rebranding and reorientation of the school’s curriculum was complete (Figure 6).

In addition to bringing several years of experience back to the school, Annett also brought his new appreciation for Power and a recognition that students would benefit from reading the magazine. He negotiated a student subscription rate from McGraw-Hill and, acting as official subscription agent for the magazine, sold subscriptions to the students. This activity, and his role in the school, gradually brought him to the attention of Managing Editor Alfred D. Blake, which resulted in an invitation to write an article. The article (on transformers), for which Annett was paid US$11, was published in the May 6, 1913, issue.[8]

Blake was so pleased with the effort that he commissioned additional articles from Annett; he contributed five more articles in 1913, 10 articles in 1914, five articles in 1915, and three articles during the first four months of 1916. The quality of these articles, coupled with Annett’s clear writing style, led, in April 1916, to an offer to join Power’s editorial staff. Annett accepted the offer, and on May 1, he left his school and began his longest and “final” career, as an author and editor — a career that eventually led him to assume the title of the first “dean” of VT writers.

References

[1] William C. Sturgeon, “Speaking of Issues: Fred Annett – A Personal Loss,” Elevator World (January 1960)

[2] Wages and Hours of Labor in the Lumber, Millwork, and Furniture Industries, U.S. Department of Labor: Bureau of Statistics (1913).

[3] Advertisement, Jersey Observer and Jersey Journal (Jersey City, New Jersey) (April 28, 1906).

[4] Letter from N.W. Murphy (Manager, New York Electrical Trade School) to a prospective student (August 27, 1906).

[5] New York Electrical Trade School Catalog (1906).

[6] “Frank M. Coffin,” Proceedings of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (Mid-October 1907).

[7] “Trade Notes,” Electrician and Mechanic, V. 20, July 1909.

[8] Fred Anzley Annett. “Decreasing Frequency of Transformers,” Power (May 6, 1913).

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.