NYC as Resurgent Skyscraper City

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat will stage its 2015 International Conference in New York City (NYC) on October 26-30. The conference title, “Global Interchanges: Resurgence of the Skyscraper City,” reflects the dramatic upsurge in skyscraper investment, design and construction that has occurred in the city in the past few years and shows no signs of abating.

Even though NYC has long been synonymous with skyscrapers, it was only a few years ago, after the tragic events of 9/11, that the entire typology of tall buildings was being questioned and many major firms were threatening to move out of town. The financial crisis and recession of 2008 brought on more negative predictions. But, since the recovery began, “resurgence” is the name of the game, and NYC is pushing the limits of tall once again.

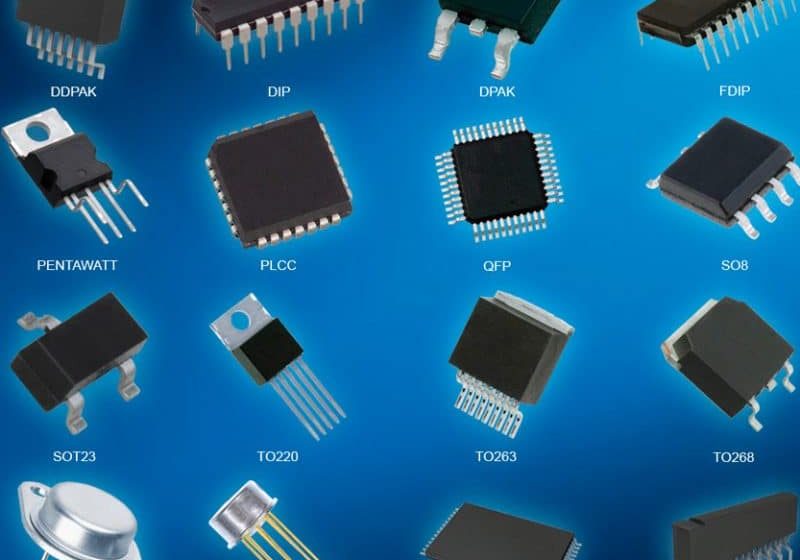

Since the turn of the decade into the 2010s, the pace of new construction in NYC can be split into two large categories: large-scale urban regeneration clusters and super-slim luxury residential infill. In both cases, developers and designers are pushing the limits of zoning, below-ground infrastructure and skyward structural engineering, including prefabrication, megaframes, bridge-like platforms over rail yards, sway-retarding dampers and cantilevers, in order to get every last square inch of potential out of high-priced high floors, as well as, to a lesser degree, provide affordable housing.

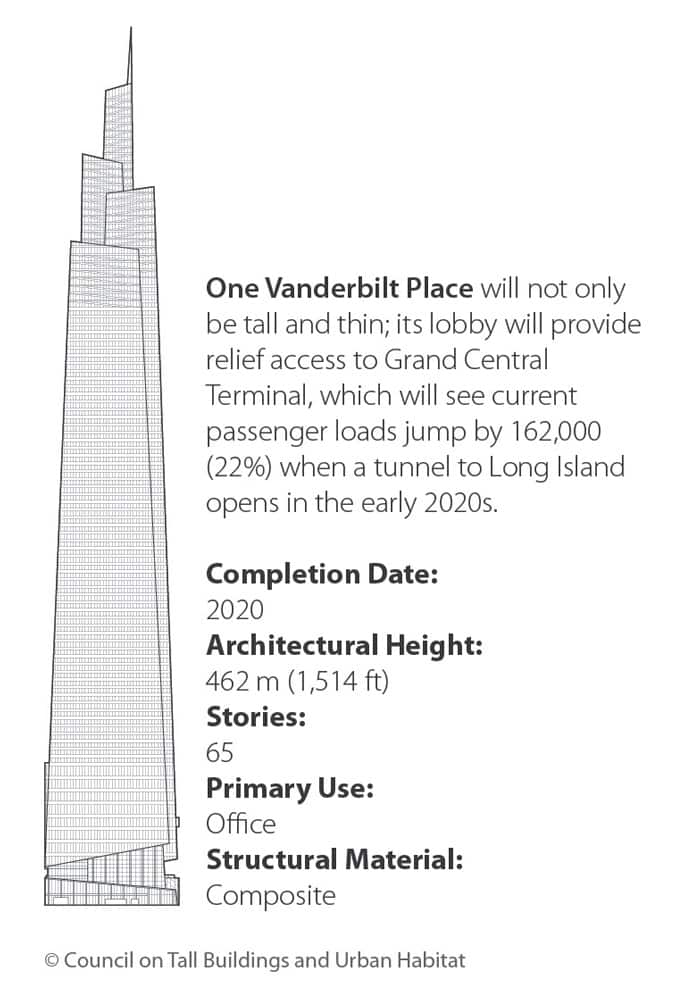

Developments under construction include the US$15-billion Hudson Yards, the largest private real-estate development in U.S. history; a residential skyscraper at 432 Park Avenue that surpasses the Empire State Building in height; and another on 57th Street – just one foot shorter than One World Trade Center (WTC) – that may become the world’s tallest residential building when completed. The tall residential typology is making its way into the Financial District, both through office-building renovations and new construction, such as the proposed 125 Greenwich Street (1,358 ft.) and the under-construction Four Seasons (937 ft.), continuing that district’s transformation from a place that went quiet on nights and weekends to a vibrant 24/7 neighborhood. The pressure of the real-estate market in Manhattan is great enough that areas of Brooklyn, Queens and New Jersey are seeing record-setting proposed tall developments around transit hubs. At Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards) in Brooklyn, construction is well underway on a mix of housing typologies using various construction methods.

WTC

One of the most-watched construction projects of the past 10 years, WTC is finally taking recognizable shape as a group of buildings that do as much for enclosing public space as they do for defining the skyline – perhaps more so than did their predecessors. With Skidmore Owings & Merrill’s (SOM) 1 WTC (1,776 ft.) and Fumihiko Maki’s 4 WTC (977 ft.) now open, along with a critical pedestrian tunnel between Brookfield Place (formerly World Financial Center), the PATH and New York City Transit subways, the WTC site is becoming recognizable as a destination, rather than as a hole in the ground to be circumnavigated. At the center of it all, the somber fountains of the 9/11 Memorial, representing the foundations of the original Twin Towers, drop water into a seemingly endless void. Although it’s impossible to avoid the gravity of the site’s history, the overall feeling is of excitement and rejuvenation, and the landscaped park surrounding the fountains is a significant improvement over the original hardscape.

Hudson Yards

Comprising 14 acres of open space and 13.4 million sq. ft. of office, retail and residential towers, Hudson Yards is an almost unimaginably large 29-acre development in space-starved Manhattan. Though the area has long been a wasteland of industrial uses, the northward advance of the High Line elevated park and the southward advance of the Number 7 subway line from Times Square promise to incorporate the development into some of the city’s most vital neighborhoods.

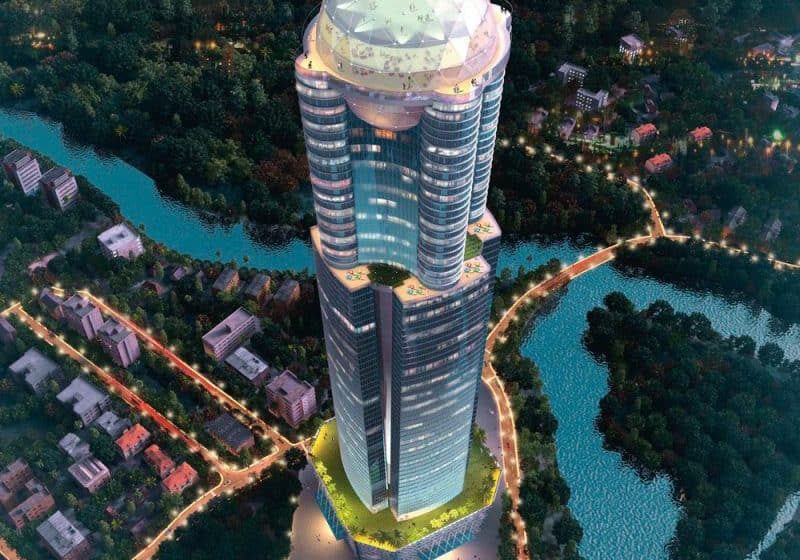

Built above the Long Island Railroad’s staging yards west of Penn Station, Hudson Yards will eventually include at least four towers of between 40 and 80 stories and a moving canopy called the “Culture Shed” by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Rockwell Group – and that’s just on the eastern half of the property. The two commercial towers by Kohn Pedersen Fox bookend a large retail podium, standing across a new public square from residential towers by tall-building ace David Childs of SOM and novices DS+R/Rockwell. Commercial tenants L’Oreal, Time Warner, Coach and SAP have all committed to the project, while a piece of public art by Thomas Heatherwick, whose urchin-shaped UK Pavilion was the talk of the 2010 Shanghai Expo, is set to occupy the project’s central square.

Connectivity to the urban grid, carefully calibrated phasing, and a highly curated mix of uses are all critical aspects of the future success of the US$15-billion project. Related Cos. and Oxford Properties Group are clearly mindful of the slow starts behind initially transit-poor Canary Wharf in London and other megaprojects of prior decades, particularly since the site was acquired from Canary Wharf’s bankrupt developer, Olympia & York. “We think it is critical that for all the tenants who are coming, that there will be critical mass, and it won’t just be a big construction site,” said Related’s president in charge of Hudson Yards, Jay Cross. He continued:

“That’s the beauty of mixed use: It allows us to deliver two residential towers without oversaturating the residential market. We then get critical mass in the commercial towers, and then, with those four towers, the retail now has an audience with which to populate the stores. These factors all feed on each other, and I think that a mixed-use master plan is a critical component; it also makes life extraordinarily complicated. We try not to mix uses in a single building, because it gets even more complicated. So far, we have managed to keep buildings single use without multiple entrance conditions.”

All of these factors are complicated further by the fact that no single building lies entirely on terra firma: Each dances on complex transfer beams and pylons between the tracks below. The buildings’ supporting platform alone is expected to cost between US$700-800 million.

A slightly different solution to a similar problem lies just east of Hudson Yards, where a relatively smaller project is simultaneously underway.

Manhattan West

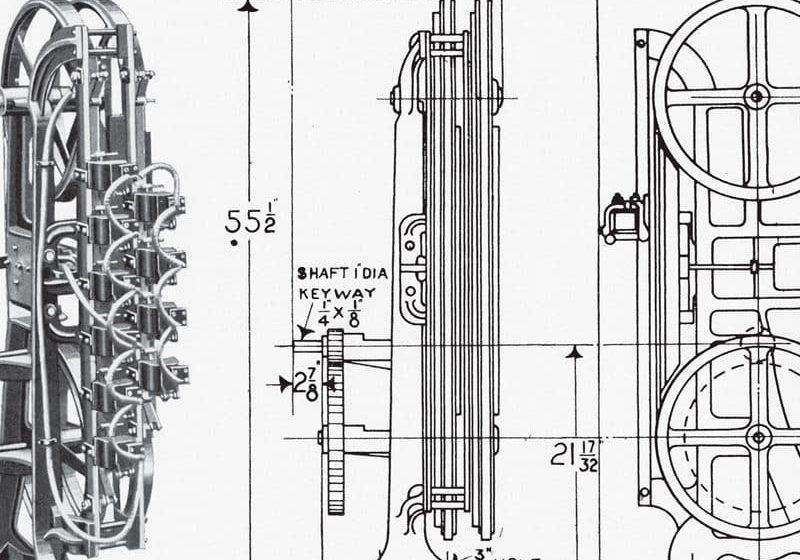

The 12-track channel taking travelers into Penn Station has been plunged into darkness, but it will be in exchange for Manhattan West’s 1.5-acre landscaped public plaza, set between two 60-plus story towers by SOM. Unlike Hudson Yards, the tower foundations at Manhattan West are on terra firma. But, in order to support the plaza between them, a highly innovative, post-tensioned, precast segmental bridge technology had to be devised to span the active rail lines below without interrupting train movements. The platform alone is a US$290-million investment, said Philip Wharton, senior vice president of development for Brookfield Office Properties, Manhattan West’s owner.

The plaza represents a continuation of 32nd Street as a pedestrian walkway that stays level, while the streets on either side drop to the west. If Brookfield can reach an agreement with Hudson Yards to its west, this corridor could theoretically provide an uninterrupted pedestrian pathway from Penn Station, and through the future Moynihan intercity rail station and both mega developments, all the way to the Hudson River and High Line.

A portion of the pedestrian corridor may pass directly through an existing building positioned over the rail yards, 450 West 33rd Street, a heavyset concrete ziggurat that once housed both the New York Daily News printing presses and stored furniture for retailer E.J. Korvette. While the building can structurally support and is zoned for a skyscraper, the current plan calls for recladding the structure and leasing to tenants in need of large floorplates, Wharton said. Including the two SOM towers, the project will comprise 6.2 million sq. ft. of office, residential and retail space.

Although Hudson Yards dwarfs Manhattan West in size, Wharton says the project’s ideal positioning between the High Line, which receives 3.5 million people per year, and Penn Station, which receives 600,000 travelers each day (219 million per year), will be beneficial for both developments. He observes:

“Retail and residential feed off each other. Retail wants to be near retail and near residential. The Fairway grocery store in the [Hudson Yards] Coach building will be great for us. Office is more competitive. But for two out of the three uses, we are very happy about the complementary nature.”

The idea that the Javits Convention Center, High Line, Chelsea art-gallery district, and Penn and Moynihan stations will be fused together at the double slipknot of Hudson Yards and Manhattan West is staggering to comprehend, even in a city used to superlatives. “It’s going to be amazing,” Wharton said. “Once this all is built out, it will be a whole other city here. There will be 25 million sq. ft. of office space, 15,000 apartments, and maybe 150,000 to 200,000 people coming to work here each day.” Transit and pedestrian connectivity is the lynchpin of success for each of these tall-building projects.

The Superslims

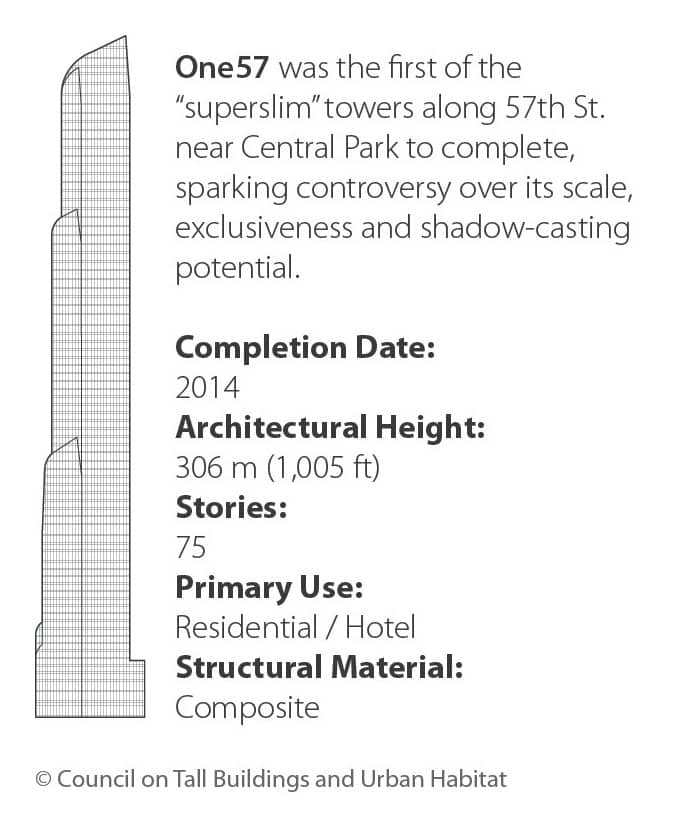

While connectivity lends cachet to large-scale developments such as WTC, Hudson Yards and Manhattan West, the tall and thin residential towers of upper Midtown are predicated on a delicate balance between proximity and exclusivity. If it could be summarized, the theme behind developments such as 432 Park Avenue, the Baccarat Tower and 111 West 57th Street would seem to be: “Right in the middle of it, yet above it all.”

Carol Willis, curator and founder of the Skyscraper Museum in Lower Manhattan, took your author and Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) Executive Director Antony Wood through the exhibition, “Sky High and the Logic of Luxury,” which examined the luxury superslim phenomenon in extraordinary detail. In addition to several human-sized scale models of the superslims, impressively lit from within, technical drawings and early study models were also on display. Willis later delivered a presentation on the subject at the 2014 CTBUH Conference in Shanghai.

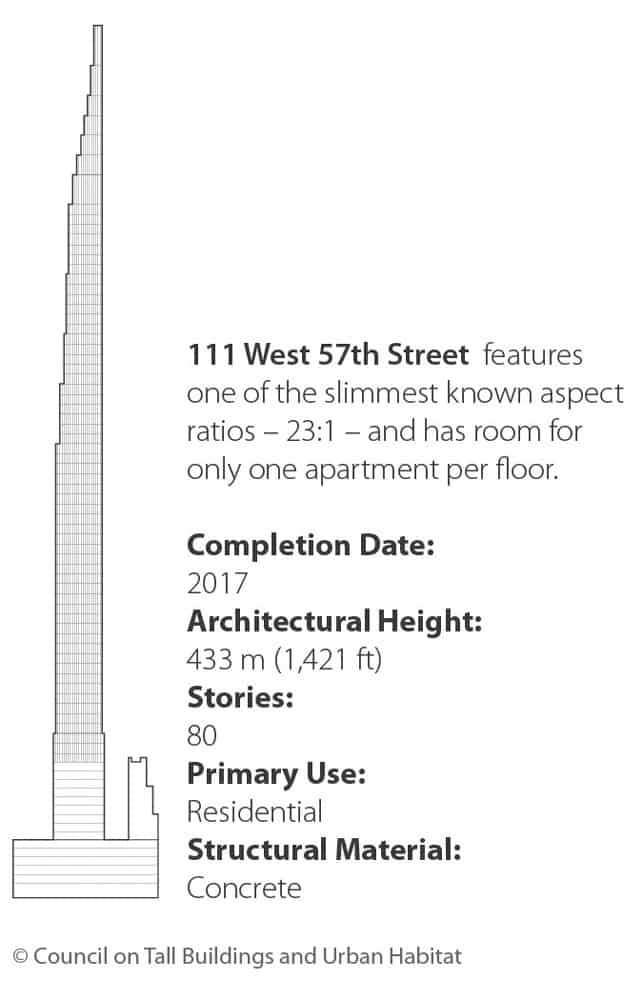

At 111 West 57th, the extreme slenderness ratio of 1:23 on the 1,421-ft.-tall, 60-ft.-wide tower may prove to be a record breaker. But the point is not to set a record, even though the building will take advantage of 15,000 lb. sq. in. concrete, once a rare commodity, and a pendulum damper to achieve this feat, according to Michael Stern, managing partner of JDS Development.

“It’s all about the views,” Stern said, articulating the well-considered (if tight) mechanics of building on a through lot that narrows to 43 ft. on the south side in order to provide apartments views up and down the island. Forty-four boutique apartments will be served by two passenger and one service elevator all the way to the top – and will be sure to command the same upper-eight-figure prices of its nearby neighbors.

Nevertheless, the building doesn’t want for architectural panache – Stern hired SHoP Architects to create what he calls a “modern version of a classic New York skyscraper, with feathered setbacks.” JDS wanted to do something different than the glassy towers that have risen of late, something “more Woolworth’s than Dubai. Somehow, we’d gotten away from the romance, and we want to get back to that,” Stern said.

Although he hired SHoP on the strength of its “nerve” for cladding the contentious Barclays Center in COR-TEN® steel, he insists he is not a big risk taker. “NYC multifamily housing is the most stable asset class in the world,” he said, citing his lengthy experience with mid-rise towers. “No one pays attention until you do a tall one.”

NYC’s tall-building market has apparently bifurcated into two distinct trends – one in which the public realm has reasserted itself with new vigor and another in which exclusivity rises to godlier heights than ever before.

Projects such as the 1,397-ft.-tall 432 Park and the Baccarat certainly want people to pay attention, though attention seems to be lavished mostly on interiors. The Baccarat sales office is paneled in burled walnut, rare forms of granite and other stone, and, of course, crystal fixtures and glassware, while the 432 Park marketing suite features a full-sized mockup of an apartment in the building, culminating in a special promotional film that can be seen only at the suite.

A visit to CIM Group and Macklowe’s 432 Park’s marketing suite in the GM Building is a highly orchestrated ballet, in which one moves past carefully chosen modern art pieces and photographs of interwar New York cityscapes and cultural icons of the period. Standing inside a full-scale mockup 10-by-10-ft. window frame that characterizes the building’s look (and is meant to evoke the coffered ceiling of the Pantheon) affords an accurate approximation of the view from the tower rising just to the south.

Numerous other “moments” greet the visitor as he makes his way around the suite, including a bathroom with a 1,200-lb. marble sink. Each of the 104 units will have one, and each is brought up in one piece. This makes sense when one considers that the combined value of the apartments is more than US$2.7 billion.

The NYC tall-building market has apparently bifurcated into two distinct trends – one in which the public realm has reasserted itself with new vigor and another in which exclusivity rises to godlier heights than ever before. Time will tell whether the two morphologies remain separate or grow together to become an as-yet-unseen hybrid in Gotham.

JDS wanted to do something different than the glassy towers that have risen of late, something “more Woolworth’s than Dubai. Somehow we’d gotten away from the romance, and we want to get back to that,” Michael Stern, managing partner of JDS Development, said.

Through all of this, the increasingly global capital markets, seeking stability, have manifested themselves in NYC real estate. Here are just a few of the headlines that bring the “Global Interchanges” theme to light:

- “China’s Greenland Group Acquires 70% Stake in Atlantic Yards Project,” The Commercial Observer, October 13, 2013

- “Tishman Speyer Invests US$3 Billion in China’s Real Estate Market Over 8 Years,” The Wall Street Journal, January 7, 2014

- “NY’s Silverstein Properties Bets $2.2 Billion on China Free Trade Zone,” Forbes, January 28, 2014

- “Trump Organization to Develop a Trump Tower in Mumbai,” Fortune, August 12, 2014

- “Japanese Firm Snaps Up Controlling Stake in New York’s 55 Hudson Yards,” New York Daily News, January 6

New York’s dramatic skyline, more than a century in the making, has been the envy of cities around the world for years. From the very birth of the tall-building typology, NYC has been at the forefront of the scene. By the end of 2015, it will be home to 239 buildings of 150 m or greater in height. This number, more than any other city save Hong Kong, makes up 7% of the global total and 35% of the tall buildings in the U.S.

In addition to these impressive figures, NYC has enjoyed many records, including being the location of the first 150-m-tall building and the first supertall (300-m-tall) building. A remarkable 10 of the 15 skyscrapers that have enjoyed the title of the “World’s Tallest” were located in NYC, giving the city the title for a combined total of 84 years. The city’s accomplishments, including both historic and planned/under-construction buildings, are impressive when examined in isolation, as well as a part of the global whole.

Get more of Elevator World. Sign up for our free e-newsletter.